THE materials you choose for the construction of your furniture will have a considerable influence on the total effect.

Basically excellent designs can be ruined by an inappropriate choice of woods, hardware or finish. On the other hand, designs of mediocre character can gain a great deal of distinction through an imaginative choice of materials. A well chosen knob, a brass ferrule, a beautifully figured piece of wood, a cane door, a plastic or marble top, can often enliven an otherwise pedestrian design and make an object of great beauty from a very simple set of lines and proportions.

Actually a design and the materials from which it is made are inseparable. Woods, metals, plastic, glass, etc., are the things of which furniture is constructed. It is very easy to fall into the trap of becoming fascinated with a set of lines on paper and lose sight of the final object. Many find that until they've had a little practice at it, visualizing a three-dimensional object from a few two dimensional lines is difficult. To help yourself get to a point where you can visualize the shape of the finished product reasonably well from a two-dimensional sketch, try working the whole thing backward once or twice. Take some object of furniture that you already have in the house and reduce it to the type of working sketch that you will be making of your new hi-fi cabinet. It takes a bit of practice to be able to visualize this transformation in advance. But you'll find it isn't too difficult after you've tried it a few times.

The list of materials and chemical compounds used at one time or another in the manufacture of furniture is practically endless.

In addition to wood, what with varied metals, plastics, fabrics, ceramics, glass, leather, etc., the list encompasses practically every thing known in the animal, vegetable and mineral kingdoms.

However, the greater part of the material in any given cabinet will be wood.

Woods

There are a tremendous number of species and varieties of woods. They range in color from bone white, through pinks, grays, greens, tans, browns, reds and violets, to jet black. They vary in hardness from woods like lignum vitae or ironwood, which can ruin the edge of an ax; to soft woods like balsa which will crumble in your fingers.

You could easily spend the rest of your life studying woods and still not know them all. The study becomes more fascinating the deeper you get into it. For example, some of the names are amusing. A tropical American wood is called bleeding heart and an other called stinking toes. One from Honduras is called billy webb, and one from Australia woolybutt. There's a South American wild dilly and one from Australia called messmate stringy bark. India has dhup and hnaw. There are others named ita, oro and uhu and one called hoobooballi! Characteristics of woods However, for the most part we use a fairly limited number of woods for our furniture work because of economic considerations, lack of supply, or because many do not have the right properties.

Certain characteristics should be kept in mind when choosing woods for cabinet work. The wood must be reasonably hard so that it will withstand normal use without chipping, denting, split ting and otherwise deteriorating before its time; and also so that it will accept fastening and jointing.

A good cabinet wood should have an interesting grain pattern.

This is particularly important in Modern designs where the visual interest is so dependent upon the figure of the wood, rather than decorative details.

Texture and grain

A wood that has too strong a figure in its grain will tend to obscure the basic lines and proportions of the cabinet. Still another desirable feature in cabinet wood is that the texture be even and the pore structure be reasonably small and uniform so that the wood will take a stain, and finish to a fine, smooth surface.

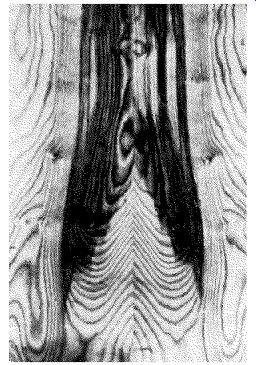

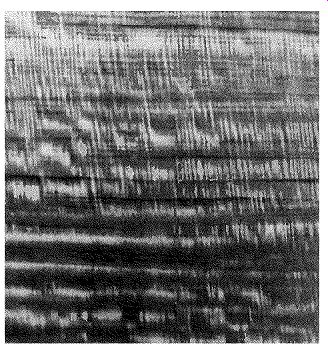

Fig. 501. African mahogany is a widely used wood with a fairly pronounced

grain. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

Very often it is necessary to stain, bleach or tone a piece of furniture to the final color desired. This can be done only if the wood you choose has a sufficiently even pore structure to accept the stain evenly, and preferably without excessively obscuring the figure of the grain. A suitable wood should not be subject to much warpage once it is seasoned. It should not have a high content of oils or resins or it will not glue satisfactorily, nor will it finish well.

Since wood is a product of nature, no two trees are exactly the same, not even two of the same species. Therefore different pieces of wood of the same species will not exactly match each other.

This is nothing to be worried about, since it is in the variations of grain and color that much of the beauty of wood is to be found.

Gross mismatches in color can generally be toned to a pleasing blend in the finishing process. Let's look at a few of the species commonly used for furniture at the present time, and see if you don't find one among them that will serve your purposes admirably.

Mahogany

Mahogany is actually a family name for a group of closely related tropical woods--at least 37 of them.

Fig. 502. Honduras mahogany, although not

as widely used as the African, is nevertheless a popular wood where

cabinetry is concerned. (Courtesy Hard wood Plywood Institute.)

They grow over quite widespread areas, including parts of Central and South America, India, the Malay States, Indochina and the East Indian Islands such as New Guinea, Borneo, Java, etc., and the continent of Australia. The trees are fairly large; a trunk diameter of a couple of yards is not uncommon.

More furniture is made of mahogany than any other single kind of wood. In all probability, more furniture is made of mahogany than all other species put together. "Why this particular wood has become so popular among makers and users of furniture begins to be understandable when we compare its properties with those listed as being desirable in a furniture wood. It has just about all of them.

Ideal cabinet wood is rather like Socrates' ideal man, moderate in all things, and mahogany fairly well fills the bill. It is moderately hard: tough enough for adequate durability, yet not too hard to be easily worked with hand or machine tools. It has a beautiful striped grain that provides the visual interest necessary to break up the large planes so often necessary in hi-fi furniture. At the same time the figure is sufficiently subdued and orderly so that it will not overpower the more important lines and proportions of your design. In mahogany of a given type, there is a good deal less variation of grain and color than in many other types of woods, making it easy to match one piece to another.

Fig. 503. Luan or Philippine is not a true mahogany. Some resemblance

is there, but the pore structure, coarseness of grain and other disadvantages

are sometimes out-weighted by its economy. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood

Institute.)

Often two or more pieces of furniture must be built at the same time to go reasonably close together in the same room. The colors of the finished units must match each other closely. In these circumstances, the relative color uniformity of mahogany is a great boon. It is much easier to get several pieces of furniture to match each other after they're finished if the wood from which they are constructed is close in color to start with. By the way, the natural color of mahogany is not the rather dark red-brown that many people think but a fairly light pinkish color. The traditional deep red-brown color so often associated with mahogany is a stained color-not the natural color of the wood at all-which brings us to another favorable aspect of mahogany. It can be finished in an extremely wide range of colors varying from a blond, which is practically white, to a jet black.

The most commonly used varieties are African, and Honduras mahogany. African mahogany (Fig. 501) has a more pronounced and evenly ribbon-striped grain than the Honduras (Fig. 502) and for this reason it is the preferable of the two. In addition, African mahogany tends to have a somewhat finer pore structure.

There is another wood variously known as Luan or Philippine mahogany (Fig. 503) which is sometimes classed with mahogany.

Fig. 504. Walnut, because of its work ability, durability color and

beautiful grain structure, 1s the choice of furniture makers. Never out

of favor, a close look at this piece shows why. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood

Institute.)

This covers a group of trees that are not true mahogany but have a similar grain. It is much coarser than mahogany and, although

it is sometimes available in ribbon-striped grain, most of it does not have this characteristic. The wood tends to chip rather easily.

The coarseness of the grain and softness of the wood also make it much more difficult to finish. It will take stains reasonably uniformly and is satisfactory for dark-colored work. Although some lumber people claim it will bleach well, experience with it has been uneven and bleaching is not recommended. Its natural color is very similar to the medium light pink of true mahogany. The main reason for the use of Philippine mahogany is the price differential-it costs about two-thirds as much as true mahogany.

Walnut

Walnut (Fig. 504) is an extremely beautiful wood. A Temperate Zone plant, the tree is plentiful both in this country and in Europe. Compared to the mahoganies the walnut tree is a pigmy.

The trunk size of walnut (2 to 2½ feet) is a bit deceiving, how- ever, since there is a band of sap wood several inches thick around it which must be cut away before the darker heart wood, used for furniture work, can be obtained.

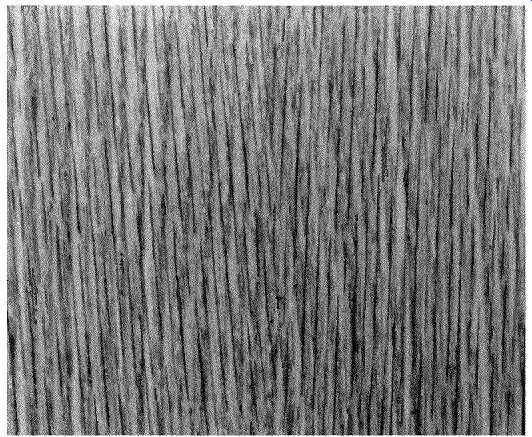

Fig. 505. Despite the difficulties encountered when working with birch

it is one of the finest natural blond woods available. (Courtesy Hardwood

Plywood Institute.)

Walnut shares many of the desirable features of mahogany. As a result, it has enjoyed extremely high favor among furniture makers for literally hundreds of years. Walnut is a wood of medium hardness, giving it the same combination of workability and durability found in mahogany. It has a strongly pronounced and very beautiful grain, sometimes appearing as a pencil stripe, or series of narrow lines of light and dark close together, or in large swirling patterns, or combinations of the two. Its grain pattern is generally far less regular than that of mahogany, introducing matching problems at times. But they are more than balanced by the visual interest and beauty of the swirling figures, particularly in Modern designs.

Although walnut will accept a wide range of finishing colors, it has been used mostly in its natural unstained color, which, when finished, becomes a rich medium-dark brown. Like mahogany, walnut has a fine pore structure, allowing easy filling and a smooth, highly polished surface.

Birch

Birch (Fig. 505) is another Temperate Zone tree, most of the American furniture grade material coming from eastern Canada and northeastern United States. The tree is small as lumber trees go. White birch is extremely light blond in color, hard, tough and springy, with a very smooth even grain. Red birch is the...

Fig. 506. Comb-grain oak is one of the faces

presented by this ever popular furniture wood. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood

Institute.)

... heart wood of the same tree and is of a light red-brown color. Birch is far harder than mahogany or walnut, which makes it more durable, but also harder to work. If you're going to make something in birch, keep the design simple so that most of it can be done with machines. If you insist on having a birch French Provincial breakfront with the carving necessary to make it authentic, hire someone else to carve it.

However, birch is an excellent cabinet material. It has most of the advantages we want. Extremely durable, it will take a wide range of finish colors with excellent uniformity. It has a figure in its grain, particularly when lightly stained, that resembles the swirls of walnut. And it has such a fine pore structure that in finishing it is not even necessary to fill to get a smooth surface that will take an extremely high polish.

Fig. 507. Plain sliced oak is characterized by a gentle swirl in its

figure. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

Since birch is naturally blond, it is a very good wood to use where a light finish is desired. Because of its blondness the graining figure is subdued. Therefore the wood is not as visually interesting as some of the others. But then a lot of people don't like a strong grain: it's all a matter of taste.

Oak

Oak has been widely used for centuries and for good reason. It is one of the larger leafy trees found in the Temperate Zone, and is widely distributed in the United States and Europe. One of the very hardest and· strongest of the domestic woods, it was used consistently in sailing days for the main timbers of ships, and is still the choice for the ribs and framing members of wooden vessels.

As a furniture material, its extreme hardness gives it tremendous durability and immense resistance to abuse. It will stand up to small children and pets long after most other materials have given up the ghost and disintegrated.

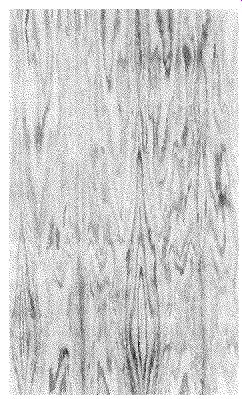

Fig. 508. One of the most complex and beautiful figures seen in wood

is found in the grain of quartered oak. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

Comb-grain or rift oak (Fig. 506) has an even-patterned grain showing a pencil stripe. Plain sliced oak has somewhat of a swirl to its figure, but not as much as birch or walnut (Fig. 507). One of the most beautiful patterns to be seen in any wood is found in the figure of quartered oak, with its contrasting longitudinal and radial lines (Fig. 508). However, along with its advantages, oak has several glaring disadvantages. While it has a beautiful grain, it has a coarse pore structure. As a result, fi11ing and finishing to a smooth surface is more difficult than with the smaller-pored woods. Due to its rather large and widely spaced pores and the extreme density of the material, it does not take stains as well as some the less dense woods.

In cost, it runs very close to walnut, which makes it one of the more expensive of the standard woods but less than the rare exotic ones.

The four woods mentioned thus far-mahogany, walnut, birch and oak-are what might be called the standards of the furniture field. An overwhelmingly large proportion of furniture is made from one of the woods of this group. However, a number of lesser known species are excellent cabinet materials and extremely beautiful woods. You may find that one of these appeals to you far more than the better known ones, so let's take a look at a few of them.

Fig. 509. Avodire, an African wood, is one of the more strongly grained

blond woods. It suits itself admirably to the Modern look. (Courtesy

Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

Primavera

With the emergence of Modern design as a dominant feature in the furniture field, there was a revolt, not only against the design of previous furniture, but also against the traditional brown coloring. This led, among other things, to a search for some interesting woods of light color.

Primavera is a Central American wood sometimes known as white mahogany. Its hardness, durability and working properties are similar to those of mahogany and walnut. It has an extremely beautiful linear grain and the kind of density and pore structure that takes stains well, but it is normally used in its natural color.

It has a very fine pore structure and will take a very high finish.

Unfortunately, it costs 40-50% more than mahogany.

Avodire

Avodire (Fig. 509) is another of the woods that has come into recent popularity along with the Modern look. It is an African wood, blond in color ranging from just off white to pale gold. It falls into the category of the medium-hard woods and is therefore in the same durability and workability class as the mahoganies and walnuts. It has a beautifully figured grain, quite strong for a blond wood. Its texture and dose, even pore structure make for ...

Fig. 510. Blond limba or korina has a grain resembling mahogany and

is some times sold as bleached mahogany. Also of African origin, it is

in wide use. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

... excellent staining properties, but like primavera, it is seldom stained.

Since it is not in as widespread use as some of the other woods, it is sometimes difficult to obtain. Then available, it runs in price generally somewhere between mahogany and walnut, and there fore is not one of the most expensive woods.

Fig. 511. Sapele is quite similar to African mahogany and is often confused

with it. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

Blond limba

Blond limba (Fig. 510), sometimes known as korina is yet another of the more recently popularized blond woods. It, too, is of African origin. Its color ranges from ash blond to a light tannish yellow in the darker streaks. It has an extremely straight, regular and even grain, tending in figure toward a pencil stripe. It has been substituted for, and sold as, bleached mahogany. Al though, in such cases, the customer is given incorrect information as to what he is buying, he is not really being fooled. In fact, if anything, he is probably slightly ahead on the deal--a wood that is naturally blond is more likely to stay that way than one that has to be bleached. For a person who wants a blond finish, a naturally blond wood is far safer.

Korina has a texture and pore structure very similar to mahogany; it finishes, therefore, just as well. It is of about the same hardness, and therefore its durability will be just as good. Korina costs a little more than mahogany. So if someone has sold you korina as blond mahogany, smile smugly and go away happy be cause you have come out a little bit ahead on the material.

One final word in favor of limba is that it is more likely to be readily available than either avodire or primavera, since it is more widely used.

Chen Chen

Another blond African wood, which is, unfortunately, rather rare, is Chen Chen. It ranges from an off-white cream color to a pale yellow. It is figured with strongly pronounced ribbon stripes similar to mahogany.

An extremely beautiful wood, its texture and pore structure are well adapted to accept coloring as desired and it is easily finished.

Sapele

Sapele (Fig. 511) is an African wood similar to African mahogany. It is about as hard and has the same color, texture, pore structure and grain, but an even more pronounced ribbon stripe.

Sapele is often sold as mahogany. The only advantage to buying it is that it generally costs a little bit less than mahogany. There's no particular reason for this except that sapele is not as well known and therefore the price isn't quite as high.

Teak

Teak (Fig. 512), has been a material of major importance in the Orient for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. It is found in the forests of Malaya and India-China and on the major islands of the East Indies. A hard, heavy, dense wood that comes from an extremely large tree, it has been used for all purposes, from architectural construction and shipbuilding to small sculptured fig urines.

When finished to its natural color, teak has a medium-dark, rich red-brown color. It is somewhat darker in color than natural mahogany, but lighter than natural walnut.

Teak has a moderately coarse grain, but not as coarse as oak. It is generally seen finished in its natural color, often with just an oil ...

Fig. 512. Teak has been used for literally thousands of years. Its color

and grain are such that it makes a striking material when properly

used. (Courtesy Hard wood Plywood Institute.)

... finish. Unfortunately it is very expensive, which limits its use. It generally costs about twice as much as mahogany.

Maple

Maple is an excellent heavy, hard, strong material having many of the characteristics of birch; it is blond, very hard, has an extremely close grain and a rather subdued figure.

Maple occasionally turns up extremely beautiful: and unusual graining figures: one is called birdseye maple (Fig. 513), another curly maple (Fig. 514) and a third blistered maple. While these ...

Fig. 513. One of the most beautiful and w1 usual grains found is birdseye

maple. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

... figures are extremely beautiful when properly used, they are rather irregular and rare in occurrence in the wood itself, and are some times difficult to obtain.

The working, staining and finishing properties of maple are closely akin to those of birch.

Fig. 514. Curly maple is another example of the striking configurations

of which this wood is capable. (Courtesy Hardwood Plywood Institute.)

Fruitwoods Fruitwood is a sort of catch-all term for several different woods occasionally used for furniture. The most used fruitwoods are cherry, pear and apple. Of these, cherry is by far the most common.

The fruitwoods are heavy, strong, durable and close-grained.

They vary from each other primarily in color and markings.

Cherry runs from light to medium reddish brown in color, with a rather well-defined figure. Pearwood is a light, rosy pink with alternate light and dark shadings forming a large, mottled figure, considerably larger than the figure of cherry. Apple is also a light reddish color, with a more subdued figure than that of either cherry or pear.

None of these woods is apt to be in plentiful supply. If you want to use a fruitwood, try cherry; it will be the easiest to find.

A great deal of what is called fruitwood furniture is actually a fruitwood color simulated on either mahogany or walnut, and sometimes birch. If you like the fruitwood color but can't find the wood itself, a skillful finisher can simulate the color on one of the three more readily available woods just mentioned.

Gum

Gum is listed last among the hardwoods, not because it's the least used, but because it is the least desirable. Gum is hard, heavy and strong and is the most inexpensive of the hardwoods. These features are good, but it has a number of disadvantages.

In the first place, it has an excessive tendency to warpage, and therefore cannot be used for any large areas without numerous internal supports.

Gum occurs as so-called white and red gum. The names refer, respectively, to the sap wood and heart wood of the same tree.

The white gum is pinkish white, while the heart wood, or red gum, is a light reddish brown. White gum has practically no discernible grain figure, but is very often discolored with mineral streaks and other markings.

In addition to the graining and color irregularities found in red and white gum, the two types are usually mixed in the same piece of lumber or plywood, leading to additional irregularities.

All in all, it's just not a very pretty wood. It's perfectly good for use where strength and expense are the main factors.

In finishing, it is best to paint or lacquer gum a solid color so that the grain is completely obscured. It will take a solid-color finish perfectly well, because it has a close grain and a very hard, smooth surface.

Knotty pine

Two soft woods are used often enough to require mention: one of them is knotty pine.

Knotty pine is used in furniture, most often for Colonial style reproductions. It is also used for wall paneling and for the construction of built-in wall treatments.

Pine has a flat and uninteresting grain. Knotty pine is consider ably enlivened by dark knots against the lighter yellow back ground. One of its most attractive features is its low cost.

Fir

The second soft wood, and the last of the woods requiring mention, is the inevitable fir.

Fir is normally used in the form of plywood and is a good utility material for surfaces that will not show, such as backs, bottoms and ...

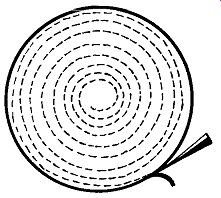

Fig. 515.

One of the ways in which veneer is produced is through the use of the

rotary cut. The wood is peeled from the spinning log in a thin sheet.

... baffle boards in speaker enclosures. It should not, however, be used for any surfaces that will be exposed, except in the case of utility cabinets (such as experimental enclosures) or units that are to be painted to match the wall. I make this recommendation not because fir plywood is weak; but because it is ugly.

Fir tends toward an extremely wild grain, takes stain unevenly and is too soft to take a high finish.

Since it is far and away the cheapest of the standard plywoods, it is the material of choice for concealed parts, because you can save money this way. It is also entirely acceptable as the base for the lamination of plastic sheets such as Formica or :Micarta. If these materials are laminated properly, there is little or no tele graphing of the underlying grain.

Fir is often used as the core in the manufacture of plywood that is later surfaced with a hardwood veneer. While the very best grades of plywood are not made in this manner, it forms a satisfactory material.

The various wood grain and figure patterns of face veneers used in hardwood ply wood are determined by three main factors: 1) the part of the tree from which the veneer is cut; 2) the method of cutting (Quartered sliced veneer for example, shows a stripe produced by cutting across growth rings. In flat cut-or half round veneers the pattern is determined by the angle at which the knife passes through the growth rings. Rotary cut veneer, on the other hand, shows a highly figured and irregular pattern also occasioned by the angle at which the knife cuts through the growth rings; 3) the species of tree. From some species many figure types are cut. From most species however, production is limited to one or two figure or grain types.

Types of veneer cuts

Most furniture being built today is constructed of veneered plywoods rather than solid woods. This is not a disadvantage, as many people seem to feel, since plywood is inherently far more stable and resistant to deterioration than solid wood.

Since most of the wood part of your furniture will be veneered plywood, let's see how these veneers are cut, and how to describe the figures that result from different methods of veneer cutting.

Fig. 516 (left). A. variation of the rotary-cut is the half-round. This

operation produces different graining effects than the rota-cut. Fig.

517 (above). The back-cut produces still other variations in the grain

of the veneer.

This will enable you to specify accurately the kind of figure you want to your cabinetmaker or lumber dealer.

Logs are cut into veneers in one of three ways: they are either rotary cut, sliced or sawed. In rotary cutting, the log is first steamed in a large vat to soften the wood. The bark is removed and the log is mounted in a lathe and turned against a cutting knife which peels off thin layers of veneer along the whole length of the log (Fig. 515). Two variations of the rotary cut are the half-round and the back cut. The log is split down the middle lengthwise and then mounted-in the case of the half-round, the curved side toward the knife (Fig. 516); in the case of the back cut, with the flat side toward the knife (Fig. 517). For both the half-round and the back cut, the knife follows a curved path through the wood, but the curve is not the same as in the rotary cut and the graining figure produced is different.

The main distinction in the figures produced by these variations is in the effect produced by the annular rings, which show up as more and more sharply defined stripes as you move from rotary cut to half-round to back cut.

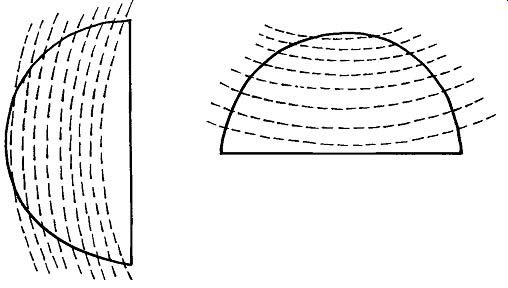

Fig. 518. Another method of producing veneer is plain slicing in which

the log is moved up and down against a knife which slices thin sheets

from it.

Sliced veneers are started by halving or quartering the log, and steaming it to soften the wood.

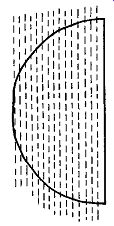

Plain slicing is done by mounting half a log in a frame that moves up and down against a stationary knife, cutting off a series of slices parallel to the center line of the log (Fig. 518). In quarter slicing, quarters of the log are mounted in a frame in such a way that the knife will cut slices at or near right angles to the annular rings, producing a figure composed of narrow straight stripes (Fig. 519).

Fig. 519. A variation of plain-slicing uses quartered logs. Called quarter-slicing,

this method results in grain patterns composed of narrow straight stripes.

Sawed veneers are relatively uncommon, due to the excessive waste and consequent high cost involved. Where this method is used, the half or quarter of the log is passed through a special veneer saw, either a rotary or handsaw, and straight slices are made, similar to the plain slice or quarter slice.

One other cut should be mentioned: you will probably run into it only in connection with oak. It is the so-called "rift cut" and is produced from quartered logs. They are cut in the same manner as quarter-sawed logs, except that the angle of the knife to the annular rings, instead of being at right angles, is 15° or so beyond. This produces, in oak, the evenly-spaced pore structure and pencil type stripe characteristic of rift or comb-grained oak.

All the various figures in veneers are produced by the manner in which the veneer slicer strikes through the light and dark areas of the annular rings and by irregularities in the growth of the wood.

Three areas in a tree will show irregularities in the wood, which, in turn, result in particularly beautiful grain figures when sliced as veneers. One of these areas is the stump, where the wood fibers tend to twist and wrinkle around places where the roots join the trunk.

The second area is just below the crotch, where irregularities are produced by the branching out of a limb.

The third irregularity is called a burl. Burls are formed around an area where the tree was injured. A burl might be considered as the tree's equivalent of the scar tissue that forms as a result of injury to an animal. The cells divide irregularly, creating excess wood that forms in many little humps and bumps, which, when sliced, produce irregular swirls and eyes.

A good many terms are used in the trade to describe the various kinds of configurations and patterns that can occur in veneers.

Plain stripe consists of alternating lighter and darker stripes running the length of the piece and produced by quarter-sawing through the growth or annular rings. Ribbon stripes are consistently wide stripes of alternately lighter and darhr wood. It is generally found in mahoganies and woods similar to mahogany.

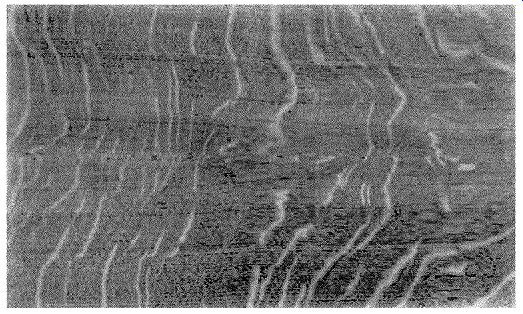

Pencil stripe is a very narrow stripe of alternating light and dark, found in walnut and limba. Fiddleback is a strongly defined rippling figure running across the grain, often seen on the backs of violins-hence the name. It is found usually in mahogany (Fig . 520) or maple.

In addition to fiddleback, several other types of markings run across the grain, all of which are often lumped together under the heading of crossfires.

Most of the veneers you are likely to encounter will vary in thickness from 1/28 to 1/16 inch. Veneers can be cut as thin as 1/100 inch. For all practical purposes, the thickest rotary-cut or sliced veneers are ¼ inch thick. Sawed veneers will, on occasion, get as thick as ¼ inch.

In the trade, wood cut up to ¼ inch thick is still considered veneer. Beyond that, it is regarded as lumber.

Fig. 520. A rather strong figure produced in veneers called fiddle/Jack.

This pattern is found primarily in maple and mahogany. (Courtesy Hardwood

Ply wood Institute.)

Types of cuts in lumber

Although the largest part of your cabinet will be plywood, it is likely that some portions will require the use of solid lumber: for moldings, edge bandings, legs or bases.

Basically, lumber is made in the same way as sawed veneers, except that the slices are thicker. Lumber will range in thickness from the ¼ inch, which is the lumber-veneer dividing line, on up through board thicknesses to timber sizes, which may he many inches thick.

Furniture work very seldom requires lumber thicknesses beyond 2 or 3 inches; most of the material that thick is used for legs.

Since lumber is sawed, the same cuts that are made in veneers are the ones that can be made in lumber-plain, quarter or rift.

Quarter or rift sawed lumber is very seldom required; therefore, there is very little of it made. The chances of your running into a situation that requires anything other than plain-sawed lumber is rather remote. For your purposes, you can pretty well consider that lumber is lumber, and disregard how it is cut. But remember that when you add a molding, frame or some other type of trim in solid material, you cannot expect an exact match of grain between the plain-sawed solid material and, for example, rotary-cut veneer plywood. You can match the colors quite accurately in finishing, but do not expect an exact match of grain where a plywood surface meets a surface of solid wood.

Types of plywood construction I have mentioned plywood a number of times, and it occurs to me that you might possibly be laboring under the illusion that "plywood is plywood," and that one is like another. Nothing could be further from the truth.

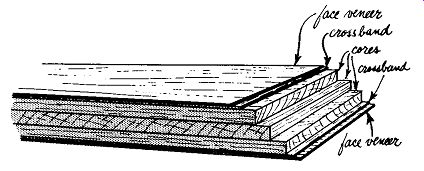

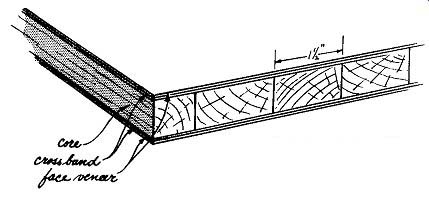

Fig. 521. Cut-away view of the internal construction of ¾ -inch veneer-core

plywood.

Plywood is constructed in several different ways, and there are various grades and classifications. All plywood constructions have this much in common: they consist of a number of layers of wood bonded together to make up the full thickness, whatever that may be, of the resulting panel. Starting from one side and going through the thickness of the plywood panel, you will find that all plywoods are made with the grain of each layer running at right angles to the previous layer.

Within the framework of these general similarities, there are several different ways of making plywood. The first and most common method results in a product called veneer-core plywood.

Since most of the material you will be using will be ¾-inch ply wood, the illustration (Fig. 521) shows the construction of ¾-inch veneer-core material.

The construction consists of two layers of veneer on the out side, cross-bands beneath each layer of veneer, and three layers of core in the middle; making a total of seven plies altogether. This is the usual method, although you may possibly run into some nine-ply material. The number of plies is always an odd value, giving a balanced construction on either side of the center ply.

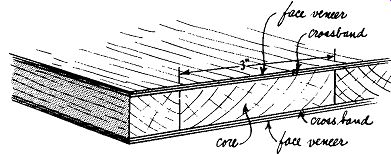

Fig. 522. Solid-core plywood differs from veneer-core in that the core

material is composed of bands of solid material edge-glued to form the

sheet of core material.

This arrangement is intended to reduce any tendency to warpage--and it does.

For material of less than ¾-inch thickness, the basic construction remains the same, but the number of plies is reduced. For example, the ¼-inch material, which you will use for control panels, will have only three plies. If you use any ½-inch material, it will generally be five-ply. Plies are always added or dropped in pairs on either side of the center. And, customarily, the core plies are thicker than the veneers or cross-bands.

The next important construction method results in a product called solid-core plywood (Fig. 522) . The veneer and cross-band layers, top and bottom, are similar to comparable layers in veneer core plywood. The difference lies in the core. In this case the core consists of 3-inch wide strips of solid wood running lengthwise through the panel and edge-glued to each other. Whichever way the annular rings of one strip of core material are curved, the rings in the strips on either side of it will curve the other way.

Solid-core plywood is more expensive than veneer-core, but is preferable. It will take edge veneers better and tends to have a smoother surface. That is to say, it has less tendency to tele graph ripples from underlying veneers and is more warp resistant than veneer-core.

Counterfront is a type of plywood that you will probably have little occasion to use except for built-in work, but you should be able to distinguish it from solid-core. Counter-front, like solid core, consists of two veneer layers and two cross-bands plus a solid core (Fig. 523). The core consists of strips I½ inches wide instead of the 3-inch strips in solid-core. The grain of both the coring strips and the surface veneers runs across the short dimensions of the panel, rather than down the length. This material is used mostly as an architectural plywood, rather than as a furniture material.

A relative newcomer to the field is plywood constructed on a core of chip or particle board. Chip board or particle board consists of wood chips or wood shavings mixed with a bonding agent and pressed into a panel. Using this board as a core, plywood is made by adding the cross bands and surface veneers. The major claims made in favor of this material are comparable warp resistance and smoothness at a lower cost than solid-core. Since the core is grainless any tendency toward warping is sharply reduced.

One thing to watch out for with these chipboard core materials is the density of the core. There is considerable variation between different chipboards. If you are going to use a plywood with this type of core be sure it is strong enough to make good, solid cabinet joints. Some are; others are not. It depends on the purpose for which they were made. Some light-density chip boards are manufactured primarily for tabletops or sliding doors, where joints are not required and where stability against warpage is the primary consideration. Such a material is likely to be un satisfactory for cabinet purposes.

On the other hand, denser-chipboard cores are made primarily for cabinet purposes.

Graining standards for veneer faces

One aspect of plywood quality is governed by the type of coring specified, another is covered in the grading of the face veneers. A plywood panel will have two face veneers, one on each side. These face veneers will be of the same thickness, but they will not necessarily be of the same quality nor even of the same material.

The price of plywood varies depending upon the grade of face veneers used. Use a good grade on any faces that will show. On the other hand, it is rather silly to go to the expense of paying for good grades on faces that will not show. For example, it is ridiculous to use good two-faced plywood for building speaker enclosures, where one of the faces will be inside and never seen.

On the other hand, a swinging door is adequate reason for the use of good two-face material.

In general, then, specify one good front face. Specification of the backing face will vary depending on the cabinet; that is to say, on how much of the backing face will show.

For your convenience, we list here the basic Hardwood Plywood Institute Grading Standards governing faces and backs of hard wood plywoods. Most of the plywood you encounter will be governed by these standards, as the major American manufacturers are members of the Hardwood Plywood Institute.

Custom grade

This grade includes special selections and types produced by individual mills, or panels of a grade description agreed upon by buyer and seller. Architectural plywoods, technical types and matched-grain panels for special uses are also included.

Good grade (1)

For natural finish--the face shall be made up of tight, smoothly cut veneer, containing the natural character markings inherent in the species. If made of more than one piece, matched at the joints to avoid sharp contrasts in color and grain, A few small burls, occasional pin knots, slight color streaks or spots shall be permitted. Knots (other than pin knots), worm holes, splits, shake and doze shall not be permitted.

Sound grade (2)

For smooth paint surfaces--the face shall be free from open defects to provide a sound, smooth surface. The veneer is not matched for grain or color. It may contain mineral streaks, stain, discoloration, patches, sapwood, sound tight knots up to ¾ inch in average diameter, sound smooth burls up to 1 inch in average diameter, hairline splits or open joints up to a maximum of 1 /64 inch. Rough-cut veneer, brashness, shake or doze are not permitted.

Fig. 523. Counter-front plywood is primarily used architecturally and

not as a furniture material.

Utility grade (3)

Discolorations, stain, mineral streaks, patches, tight knots, tight burls, knot holes up to ¾ inch in average diameter, worm holes, splits or open joints not exceeding 3/16 inch and not extending half the length of the panel, cross creaks and small areas of rough grain shall be admitted. Brashness, shake or doze are not permitted.

Reject grade (4)

The veneer shall be unselected for grain or color. Knot holes no greater than 2 inches in maximum diameter and no group of knot holes in any 12 inch square exceeding 4 inches in diameter and splits no wider than ½ inch shall be admitted. Splits ½ inch wide at widest point may be one-fourth panel length; those not more than ¾ inch wide at widest point may be one-half panel length; those not more than¼ inch wide may be full panel length.

Mineral streaks, stains and discolorations not associated with rot or doze, shims, plugs, patches, knots, burls, worm or borer holes and other characteristics are permitted, provided they do not seriously impair the strength or serviceability of the panel.

Fir plywood In addition to the grading standards used for hardwood ply woods, another set of standards has been set up for grading fir plywoods.

In spite of the fact that its exterior appearance and finishing properties suffer by comparison with the hardwoods, fir plywood, for our purposes, is structurally just as sound as a plywood with a hardwood veneer. And, in view of the cost factor, it is, for many applications, the material of choice. It would be absurd, for example, to make the backs, bottom and baffle boards for speaker enclosures out of hardwood veneer. It would be equally silly to make the internal partitions in a horn out of hardwood veneer.

Fir plywoods are made entirely in veneer-core construction and are of two types, as well as several surface-appearance grades within each type. The two types of fir plywood are differentiated by the kinds of glue bond between plies. The exterior type is bonded with a completely waterproof glue, and it is required by the standards that the glue bond test out to be stronger than the wood itself. Interior type is made with a moisture-resistant but not waterproof glue. It will stand up under occasional wetting, but is not intended to withstand soaking.

In each type there are several grades, which refer to the surface appearance of the plywoods, similar to the grades used in hardwoods. Altogether there are seven grades of exterior and nine of interior type. However, not all of them concern us.

Grading of fir plywood is by letter rather than by the numbers used for hardwoods. The following standards for face veneers in fir plywoods are quoted from official publications of the Douglas Fir Plywood Association, which sets the standards in this industry.

The standards given are minimum for each grade or, to put it another way, the defects mentioned are the largest defects that will be allowed in each grade. The largest percentage of the material exceeds the standards given for the respective grades.

Veneer grade

A Must present a smooth surface free from knots, open splits, pitch pockets and other open defects. The veneer should be well joined if more than one piece is used. Grade A admits discoloration, sap wood and pitch streak averaging not more than ¼-inch width and blending with the color of the wood; admits maximum of 18 veneer patches in a 4 X 8-foot sheet; admits shims and neatly made panel patches. The shims may not be used over or around any type of patch and multiple repairs must be limited to two patches. All patches and repairs must run parallel to the grain.

Grade A also admits approved plastic filler in splits and other minor defects up to 1/32-inch in width; in small splits or openings up to 1/16-inch in width if not more than 2 inches long; in small chipped areas or openings not to exceed ¼ by ¼ inch long.

Veneer grade B

This grade must present a solid surface, free from open defects, except splits not wider than 1 /32-inch.

Vertical ambrosia beetle borer holes are permitted if they do not exceed 1/16 inch in diameter and averaging not more than one per square foot; also horizontal tunnels 1/16-inch across, I inch in length, 12 in number in a 4 X 8-foot panel, or proportionately in other dimensions.

Veneer quality C (repaired)

This is used for underlayment grade only. Tight knots can be up to 1 ½-inches in greatest dimension and worm and borer holes or other open defects may not exceed ¼ X ½-inch. Splits not to exceed 1/ 16 inch wide are allowed. Solid, tight pitch pockets, ruptured and tom grain, minor sanding defects and sander skips up to 5% of the panel are allowed.

Veneer quality C Knotholes shall be I inch in their least dimension; pitch pockets not wider than 1 inch; splits 3/16-inch (must taper to a point). Worm or borer holes o/s X 1½ inches; tight knots--½ inch; plugs, patches, shims and minor sanding defects are permitted.

Veneer quality D

This veneer is used only in interior type plywood. Knot holes -2½ inches; pitch pockets--2 X 4 inches; splits, widths at widest point: ½ inch up to quarter panel length; ¼ inch up to half panel length; 3/16 inch up to full panel length; all must taper to a point.

Plugs, patches, shims, worm or borer holes and minor sanding defects are allowed.

Veneer quality N (natural finish)

This is a special grade. It presents a smooth surface, 100% heart wood of yellow or pink color without stain. It must be free from knots, splits, pitch pockets and other open defects.

If joined, not more than three pieces of the veneer should be used, joints to be well matched as to color and grain and all joints to be parallel to the edges of the panel.

A maximum of two shims is allowed, not to exceed 6 inches long at the end of the panel. A maximum of four well-matched small patches not to exceed 1/8 X 2½ inches is permitted.

All repairs must be parallel to the grain of the panel; neither overlapping of repairs nor plastic filler is permitted.

With these various veneer grades, different grades of plywood panels are made; the grading of the panels depending on the quality of the front and back face veneers. For example, AA grade of either exterior or interior type is good two-face. AB is good one face with the second face not quite as good as the first. On grades AC and AD the back face becomes progressively less at tractive in appearance. By the time you get down to CB, you're using a utility grade. Structurally, it's just as sound as the others but its appearance is not as good.

In a situation where, for example, Formica type plastic laminates are going to be used for surfacing the cabinet, why pay for A faces when they're going to be covered? BD is a perfectly good grade for this purpose. No one is likely to stare for hours with rapt attention at the back or the bottom of a speaker en closure. Again, this is a perfectly good use for BD grade.

Special surface veneers In addition to standard hard or soft-wood panels, several companies produce specially surfaced decorative panels primarily for use as wall surfacing. Among the various decorative effects avail able are striated surfaces, embossed surfaces, simulated tongue-in groove and parquet effects, actual tongue-and-groove strips and raised-grain effects. These special-effect panels are not desirable for a free-standing cabinet but, where a built-in wall installation is intended, some very beautiful results can be achieved by integrating the installation into a paneled wall.

I am sure that you are all familiar with at least some of the laminated plastic surfacings that are available. These appear under a wide variety of trade names: Formica, Micarta, Textolite, Conso weld, Pionite, Nevamar, etc. You are probably familiar with these sheets in the form of the rather grisly patterns used for kitchen work surfaces, bathrooms, luncheonette counters and tabletops.

These same panels are also available in excellent wood grains and in a number of solid colors. Some very exciting combinations can be achieved by the judicious use of solid colors; for example, a white top or white fronts on a walnut cabinet.

The great advantage of these materials, of course, is that they are virtually impervious to the assaults of alcohol, cigarettes, small children and pets.

Walnut grains as well as dark and blond mahoganies are very attractive in plastic laminates; oaks or birches less so.

Hardware

The hardware, or lack of it, employed in your furniture can practically make or break the design. Choose it with great care.

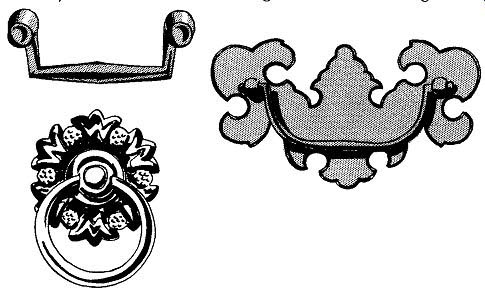

Fig. 524. Several examples of available knobs and pulls. The variety

of hardware is so great that the best thing to do is browse through a

shop or catalog until you run across something suitable.

You won't believe, until you have browsed through a really well stocked hardware store, what a tremendous variety is available.

There are literally hundreds of different knobs and pulls, as well as numerous kinds of hinges, catches, ferrules casters, gliders and various types of decorative metal trim.

Your choice of knobs and pulls is strictly a matter of taste. Look at what is available until you find something that strikes your fancy. A few types are shown in Fig. 524.

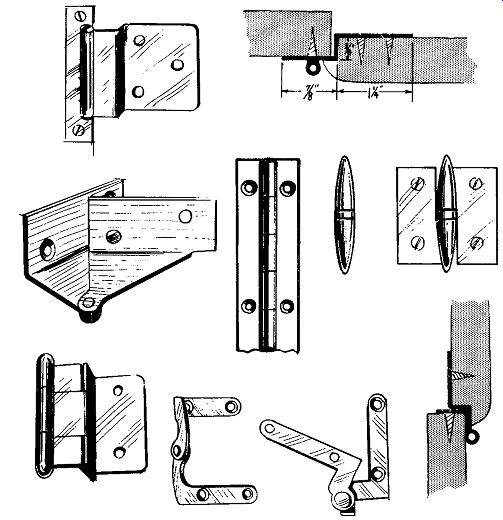

With hinges there is one practical consideration over and above appearance. ·whether you use the completely concealed type such as the Sass, the semi-concealed pivot hinges, piano hinges, butt ...

Fig. 525. Hinges are also a matter of taste. These are but a few of

the available types.

... hinges or any decorative hinges, be sure that they are capable of carrying the load of the door, lid or drop front you plan to hang on them. Fig 525 shows just a few of the available types.

As far as weight-handling capacity is concerned, the piano hinge is the strongest. The butt and Sass hinges are next. The weakest of the lot is the pivot hinge, so be careful as to how much weight you plan to load on it.

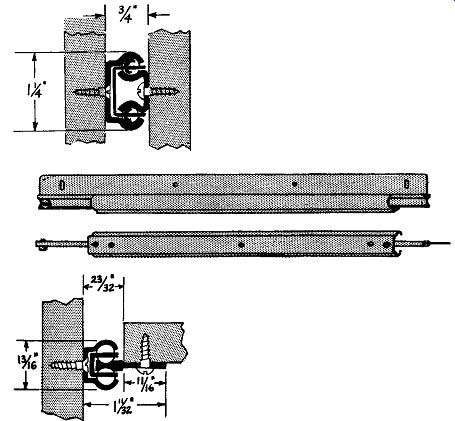

Fig. 526. Drawer slides of several types are available for equipment

that is mounted in pullout drawers of any kind.

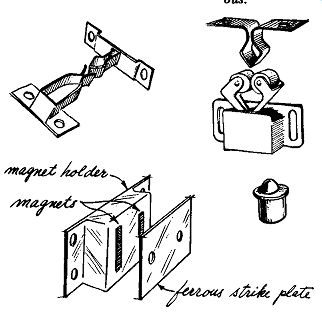

Make sure that the drawer slide will be able to carry the weight of the equipment. The drawings at the left show ball bearing catches-a few of the many different types that could be used.

Fig. 527. Door catches of various types are also available in many sizes,

shapes and forms. The bullet and magnetic types are the least conspicuous.

If you have any pullout drawers, for example, housing record changers or tape machines, you will need drawer slides (Fig. 526).

The standard type will be perfectly adequate for your record changer but, if you have a good-sized tape machine in a pullout ...

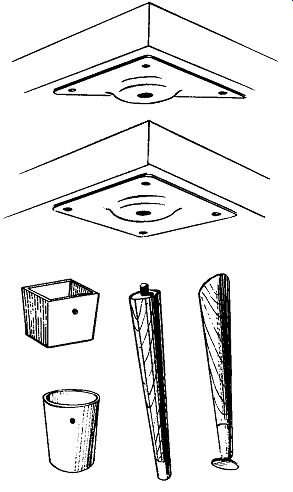

Fig. 528. Casters must be chosen with a view as to how often the cabinet

is going to be moved and how much weight it will have to carry. The one

illustrated here is a good general purpose type.

... drawer, you will probably find it will be necessary to look for some heavy-duty slides. Check the weight of the unit to be...

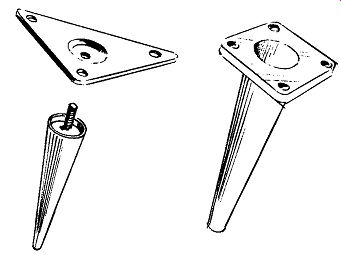

Fig. 529. Ferrules for wooden legs are available in brass. They are

primarily designed for round tapered legs.

...mounted in the drawer, and be careful to get slides rated to carry, say, at least 5 pounds over this weight.

Some slides are made for undercarriage mounting (that is, to be used under the drawer) while others are made for side mounting between the drawer and the side of the cabinet. Usually, either is satisfactory (and they'll still work perfectly well) but, if you use a slide in a manner different from the one for which it was intended, you'll change its weight-carrying capacity. So when you check the loading capacity, be sure you know which way the slide is to be mounted to give that capacity.

Of the various types of door catches available, (Fig. 527) the most inconspicuous is the bullet catch. The only trouble with it ...

Fig. 530. An example of an all metal leg. Many types are available in

brass, wrought iron or plated metal. Brass seems to be the most attractive

material.

... is that it's not too well constructed for the most part and some times tends to jam after its been in use for a time. You won't have this trouble with the spring-dip types, but they do show more.

A rather nice, recent innovation in this area is the magnetic catch. It consists of a magnet mounted in a carrier in the cabinet and a plate of ferrous metal mounted on the door opposite it. No moving parts, nothing to wear or jam. Very lovely indeed.

Casters (Fig. 528) are another item to which you have to give a second thought as to the amount of weight that is going to be placed on them. If you've got a unit that is designed for casters so that you can roll it around, be sure that you've left a good solid area in which you can attach the caster, and also that you use a large enough caster to handle the weight. Remember that the larger the caster wheel, the easier it will roll over carpets and minor obstructions such as door sills and the like.

The trouble is that by the time you've got a big enough caster so that it will roll easily, it's also big enough to be a trifle unsightly. You'll probably wind up having to make some sort of a compromise between the size that would be functionally best and the size that would be esthetically pleasing.

If you want brass tips or ferrules on the legs of your furniture, you'll find a good selection available in round ones, but not much in square ones (Fig. 529). So if you're going to use ferrules, figure on using a round tapered leg. If you want to use a leg in metal throughout (Fig. 530), there is wrought iron, which has the advantage of being very inexpensive, but brass or brass plate is far more beautiful. In brass and brass-plated legs, sizes range from 3 to 30 inches in height, in round, tapered shapes either straight or angled.

A small number of straight square legs in brass are available, but not nearly the selection that you can get in round tapers. Also, a few decorative brass legs and some decorative brass feet are avail able for use with period designs.