Classical Records--P.D.Q. Bach and Peter Schickele; Karajan's Don Carlos; Shostakovich song cycles

Reviewed by:

Scott Cantrell Abram Chipman R. D. Darrell Peter G. Davis Robert Fiedel Kenneth Furie Harris Goldsmith David Hamilton Dale S. Harris Philip Hart Nicholas Kenyon Allan Kozinn Paul Henry Lang Irving Lowens Robert C. Marsh Karen Monson Robert P. Morgan Conrad L. Osborne Andrew Porter Patrick J. Smith Paul A. Snook Susan Thiemann Sommer

BACH: Cantatas, Vols. 22-24.

Wilhelm Wiedl (in Nos. 84-86, 93-97), Marcus Klein (Nos. 88, 89), Detlef Bratschke (Nos. 91, 92), and Claus Lengert (No. 98), boy sopranos; Paul Esswood, countertenor (Nos. 85-94, 96-98); Kurt Equiluz, tenor (Nos. 85-88, 90-98); Ruud van der Meer (Nos. 85-87, 93, 97), Max van Egmond (Nos. 88-92, 98), and Philippe Huttenlocher (Nos. 94-97), basses; Tolz Boy's Choir, Vienna Concentus Musicus, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond. (Nos. 84-87, 93-97); Hannover Boys Choir, Ghent Collegium Vocale, Leonhardt Consort, Gustav Leonhardt, cond. (Nos. 88-92, 98). TELEFUNKEN 26.35364/35441/35442, $19.96 each (two discs).

Vol. 22: No. 84, Ich bin vergnugt mit meinem Glucke; No. 85, Ich bin ein guter Hirt; No. 86, Wahrlich, wahrlich, ich sage euch; No. 87, Bisher habt ihr nichts gebeten in meinem Namen; No. 88, Siehe, ich will viel Fischer aussenden; No. 89, Was soil ich aus dir machen, Ephraim?; No. 90, Es reisset euch ein schrecklich Ende.

Vol. 23: No. 91, Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ; No. 92, Ich hab in Gottes Herz und Sinn; No. 93, Wer nur den lieben Gott lasst walten; No. 94, Was frag ich nach der Welt. Vol. 24: No. 95, Christus, der ist mein Leben; No. 96, Herr Christ, der einge Gottessohn; No. 97, In alien meinen Taten; No. 98, Was Gott tut, das ist wohlgetan.

Telefunken's series of the complete Bach cantatas, directed jointly by Nikolaus Harnoncourt and Gustav Leonhardt, is one of the most important recording projects ...

-----------------

B Budget

H Historical

R Reissue

A Audiophile

(digital, direct-to-disc, etc.)

-------------

... under way. The revival of the rich and re warding music, so little known except for a few oft-repeated popular cantatas and extracted arias, is one feature of the achievement. The other is the revelatory quality of the performances. Here are the world's foremost practitioners in the art of singing and playing baroque music with the original forces, showing that Bach's cantatas do not have to sound muddy, gloomy, draggy, or otherwise religiose: that they have light ness, grace, a dance-inspired bounce, and life-giving serenity. These performances clarify the immense complexities of the big choral movements (with baroque instruments and clear young male voices, every strand in the music can be distinguished separately) and give life and breath to the long solo arias by resolutely avoiding plodding bass lines and heavily sustained legato melodies. I can rarely restrain my enthusiasm when a new set comes along; when there are three, as here, enthusiasm amounts to obsession.

There have been recent criticisms of some aspects of the performances: of Harnoncourt's eccentricities of interpretation and of the less than ideal quality of the choral singing. Little of that is evident here.

Harnoncourt now uses the superb Tolz Boy's Choir in place of the Vienna Boys, and Wilhelm Wiedl sings the treble arias with an effortful warmth that is deeply moving. Leonhardt has choirs from Hannover and Ghent, less incisive but beautifully supple. I am only occasionally irritated by Harnoncourt (as when he fades out a cadence before it has time to be heard, at the end of No. 95's first chorus); his players are brilliant in the big overture-like numbers, such as No. 97's opening. Leonhardt's performances are less thrilling (a pity he was given the large-scale Gelobet seist du, No. 91), but the playing is refined and the balance between voices and instruments in a lilting movement like Ich hab in Gottes Herz (No. 92) is perfectly poised.

What an infinite variety of responses to the texts and hymns of the Lutheran liturgy can be heard in these works! A brilliantly original aria in No. 95 depicts the tolling of a death knell (very cheerful-Bach's bells were always small and high-pitched) with pizzicato strings overlaid with sub lime, echoing oboes d'amore. The shining star of No. 96's opening chorus is depicted by a warbling flauto piccolo over pastoral strings. In No. 97 there is an alto aria, "Leg ich mich spate nieder," wonderfully sung by Paul Esswood, which has that unearthly peace and repose Bach always brings to his visions of eternal life.

The first of these volumes is devoted to cantatas for soloists only, with closing chorales. Wiedl is excellent in Ich bin vergnugt (No. 84), and a comparative new comer to the series, Ruud van der Meer, is very fine in the intricate fugal writing of Wahrlich, wahrlich and Bisher habt (Nos. 86 and 87)--Bach here sounding just like Zelenka in the Lamentations. Kurt Equiluz, re liable as ever, makes exciting work of the tempestuous Es reisset euch (No. 90), and Max van Egmond has a powerful aria with trumpet (a good bash at an impossible part by Don Smithers) in the same cantata.

There are great riches in this volume; but if you are tempted to begin collecting the series, then do start with a box containing some of the big choruses that are the back bone of these works. I especially recommend Vol. 24 from this group. And among those recently released, Vol. 20 is ideal: It includes magnificent accounts of two supreme masterpieces, Jesu, der du meine Seele (No. 78) and Gott der Herr ist Sonn und Schild (No. 79), than whose opening chorus I never hope to hear anything more inspiring. N.K.

BACH: Keyboard Works.

Blandine Verlet, harpsichord. PHILIPS 9500 588, $9.98. Italian Concerto, S. 971; French Overture (Partita in B minor), S. 831; Duets: No. 1, in E minor, S. 802; No. 2, in F, S. 803; No. 3, in G, S. 804; No. 4, in A minor, S. 805.

BACH: Goldberg Variations, S. 988. Blandine Verlet, harpsichord. PHILIPS 6768 074, $19.96 (two discs, manual sequence).

Blandine Verlet's playing is nothing if not exciting; hardly a phrase passes with out calling attention to the sheer energy and intensity of her musical personality. She has a most compelling sense of rhythm (projected as much by bold articulation as by actual timing) and a healthy notion that even slow movements should maintain a strong feeling of forward motion.

With a work like the Italian Concerto, Verlet is in her glory, sending off sparks in every direction. The electricity is especially palpable in the last movement, but even in the Andante there is a concentration of energy that eludes all too many ...

---------------

P.D.Q. Bach and Peter Schickele, by Lawrence Widdoes

-----

Recalling my early involvement in P.D.Q. Bach research, I approached this assignment with a feeling of mild paranoia. My working relationship with the re doubtable Prof. Schickele was, of course, a happy one--at first. But after a time I began to sense some rather alarming changes in myself. My musical consciousness had be come cluttered with surrealistic images. To my horror, for example, I imagined Frederic Chopin, small, pale, and coughing, loitering in the Place Vendome, grinning, and pinching the rumps of carriage horses, making them cry out in pain. I saw Felix Mendelssohn, superbly accoutered but picking his nose in public. Perhaps most shocking of all was the vision of Richard Wagner, somewhat rueful of face, actually paying off a debt! Shaken, I finally reported these disturbing visions to Prof. Schickele. He simply smiled seraphically (or maybe drunkenly, now that I look back on it) and congratulated me on my newfound maturity and realism. I knew then the time had come to take up other pursuits.

The professor's research goes for ward, however, and the music of P.D.Q.

Bach receives continued indecent exposure in concerts and recordings. What makes the phenomenon endure? Schickele has ...

------

Lawrence Widdoes, a composer, was instrumental in early P.D.Q. Bach research; readers of the Definitive Biography will recall his devoted restorations of the beer-stained manuscripts. An artist to boot, he also takes responsibility for the rendering above.

------

... been carrying on now for more than twenty-five years, if memory serves, yet the latest annual Christmas concerts at New York's Avery Fisher Hall were packed, as always. And this year's national tour will include no fewer than fifty-five concerts.

Could Anna Russell have played to such audiences? After her great Wagner skit and a few minor tidbits, she had little more to offer. Victor Borge, with his five or six excellent routines, fills a Broadway theater, but not every year. Joshua Rifkin's short lived foray into musical humor, the "Baroque Beatles Book," was well done-per haps too well done, and a bit chilly. Schickele's only serious contender might have been Gerard Hoffnung, whose early death makes the point moot.

Schickele's admitted early inspiration was that fountainhead of American musical humor, Spike Jones, and Schickele's humor, like Jones's, is distinctly American. Russell, Borge, and Rifkin had about them a certain sophistication that Schickele, at his best, utterly lacks. His slapstick, pratfall sort of humor is often so terribly self-indulgent, outrageously sophomoric, and inexcusably bad that we find ourselves laughing not so much at the jokes themselves as at his nerve in trying to pull them off. Thus, the hiss and the boo have become accepted responses at the concerts, ultimately eliciting a deliciously crummy comeback from Schickele that might have come from a men's-room wall: "Truth is a statue, and all of you are just a bunch of pigeons." Musically, too, the humor is unmistakably American: slipshod cadences, embarrassing country and western melodic fragments, blue notes, unexpected dissonant clusters, outdated scat phrases such as "shoop-doo," Guy Lombardo endings, and ridiculous-sounding homemade instruments. All of these carefully calculated in congruities are familiar, of course, from the music of Spike Jones. But their use by Schickele in the context of baroque music is even more striking, because the general style of that era is by now so familiar, and it represents the epitome of periwigged musical dignity and sophistication.

The latest recording, the eighth in the P.D.Q. Bach research series, is the weakest, for some of the reasons already discussed: The music is almost too good and too careful. There is a slick quality to the "discoveries" and performances not in keeping with the composer's familiar sleazy style. The Bluegrass Cantata sounds a bit self-conscious, lacking the earthy clumsiness and mellow tackiness of earlier works. It is all too cool now. Gone are the gutsy slapstick of the "Hysteric Return" recording, the glorious wackiness of the Beethoven Fifth sportscast, the inspired lunacy of the fugue from the Toot Suite. The quotations from the Brandenburg Concertos seem dutiful, lacking the unstudied ease of previous plagiarisms. This is not to say that the cantata lacks all charm; the aria "Du bist im Land" is wonderful, and the work does have arousing finish. The performances especially those of Eric Weisberg (mando lin), Bill Keith (banjo), and tenor John Ferrante-are marvelously skilled.

The No-No Nonette features a single percussionist but a wide and peculiar array of percussion instruments. Though it occasionally offers some funny sounds, the instruments do not really fit the fabric of the music as do, for example, the unusual instruments in The Seasonings; here they are simply lined up and played one after the other. Hear Me Through, one of the singing commercials that reputedly made P.D.Q.

Bach so wealthy, is a rather pale reworking of an earlier commercial from "P.D.Q. Bach on the Air" (Vanguard VSD 79268).

For all its faults, the new album will, of course, be indispensable to fellow camp followers, who have discovered that being slightly deranged is a wonderful and re warding way of life. But it is not the best introduction to the music of this zany com poser. The deprived few still to be initiated will do well to start with "On the Air" or "The Intimate P.D.Q. Bach" (Vanguard VSD 79335); from there on, you are perilously on your own.

Far more welcome at this point is a disc that affords us an all too rare sampling of the "straight" (I refuse to say "serious") music of Peter Schickele. He is currently represented in SCHWANN by only two listings: Fantastic Garden (Three Views from the Open Window), with Jorge Mester and the Louisville Orchestra (Louisville S 691), and The Lowest Trees Have Tops for soprano, flute, harp, and viola, performed by the Jubal Trio and John Graham (Grenadilla 1015). Another work, Pentangle for horn and orchestra, will also appear shortly on the Louisville Orchestra label. Schickele has, of course, written an enormous amount of non-P.D.Q. Bach music, and I have heard much of it. It is frequently strong and highly individual and always expert. Why has Vanguard been so slow to give it to us? Schickele is a large, gentle, sensitive, and often funny man, and these are precisely the qualities he exhibits in his com positions. Stylistically, he is quite versatile, as is apparent from the contrasting sides of this recording. A single style would be entirely too constricting for him.

The Knight of the Burning Pestle is a seventeenth-century play by Beaumont and Fletcher that was turned into a musical by Schickele and American director Brooks Jones in 1974. The nine songs presented here are broadly funny and occasionally lyric and touching. They are quite tonal, varied in character, with typically accomplished arrangements-direct, unfussy, and very attractive. "My Mother Told Me Not to Worry," the most beautiful of the lot, is very dose to current pop and performed accordingly by Margot Rose. Elsewhere, there are faint reminders of Kurt Weill. Side 2 is made up of sterner stuff.

This is the facet of Schickele we would all like to hear more of. (Yes, we still love you, P.D.Q., but please take the backseat for a while.) The elegies for clarinet and piano represent him at his melodic best, with a wonderful liquid flow to the clarinet lines that proves irresistible. The first two are dedicated to a friend and a relative now de ceased, and they must have been nice people; there is an affecting, slightly bluesy quality to both numbers, and the major/ minor/dominant ninth tonal scheme is sufficiently varied. On the other hand, the repeated triads in the third number, characterized as a sort of "ritual ... after the eulogies have been given," are a bit wearing.

The Summer Trio is the strongest work here. Less closely tied to major/minor tonality, it has a bristly insistence. The slow music is lyrical but not gooey, and the jazz walking bass in the second movement is very well handled, without a trace of the archness such a device can fall prey to.

Though this music has no place in the avant-garde (whatever that means to day), there is much enjoyment to be had here. It seems a pity that a composer of Schickele's obviously superior gifts should spend comparatively little time composing and promoting his own music.

---------------

P.D.Q. BACH: Black Forest Bluegrass.

John Ferrante, tenor; Peter Schickele, bass; New York Pick-Up Ensemble, Robert Bernhardt, cond. Wind octet and percussion, Schickele, cond.' Ferrante, bargain counter tenor; Schickele, snake; instrumental ensemble.** [Seymour Solomon, May nard Solomon, Peter Schickele, and William Crawford, prod.]

VANGUARD VSD 79427, $7.98.

Blaues Gras ( Bluegrass Cantata); No-No Nonette; Hear Me Through.

SCHICKELE: The Knight of the Burning Pestle: Songs (9). Elegies.' Summer Trio. Lucy Shelton, soprano; Margot Rose, alto; Frank Hoffmeister, tenor; Robert Kuehn, baritone; instrumental ensemble, Peter Schickele, cond. Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Schickele, piano.' Walden Trio. [ Seymour Solomon, Peter Schickele, and William Crawford, prod.]

VANGUARD VSD 71269, $7.98.

------------------------

Critics' Choice

The most noteworthy releases reviewed recently

BACH: Brandenburg Concertos, S. 1046-51.

Aston Magna, Fuller. SMITHSONIAN RECORDINGS 3016 (2), Dec.

BACH: Suites for Orchestra, S. 1066-68, et al.

English Concert, Pinnock. ARCHIV 2533 410/1 (2), Nov.

BARTOK: Piano Concertos Nos. 1, 2. Pollini, Abbado. DG 2530 901, Feb.

BEETHOVEN: Missa Solemnis, Op. 123.

Bernstein. DG 2707 110 (2), Jan.

BEETHOVEN: Piano Sonata Nos. 21, 31.

Goldsmith. MUSICAL HERITAGE MHS 4005, March.

BERG: Lulu. Stratas, Boulez. DG 2711 024 (4), March.

BERLIOZ: Harold in Italy. Suk, Fischer Dieskau. QUINTESSENCE PMC 7103, Nov.

BRAHMS: German Requiem. Kempe.

BRUCKNER: Te Deum. Forster. ARABESQUE 8007-2 (2), March.

DEBUSSY: Preludes, Book I. Rev. SAGA 5391, Feb.

DVORAK: Cello Works. Sadlo, Holetek, Neumann. SUPRAPHON 1 10 2081/2 (2), Jan.

HAYDN: Armida. Norman, Burrowes, Dorati. PHILIPS 6769 021(3), March.

HAYDN: Symphonies Nos. 82, 83. Marriner. PHILIPS 9500 519, Feb.

HINDEMITH: Mathis der Maier. Fischer Dieskau, Kubelik. ANGEL SZCX 3869 (3), Feb.

MOZART: Don Giovanni. Raimondi, Maazel. COLUMBIA M3 35192 (3), Feb.

MOZART: Quintets for Strings (6). Budapest Quartet. ODYSSEY Y3 35233 (3), Feb.

SCHUMANN: Orchestral Works. Bavarian Radio Symphony, Kubelik. COLUMBIA M3 35199 (3), Jan.

SIBELIUS: Violin Concerto.

SCHNITTKE: Concerto Grosso. Kremer, Rozhdestvensky.

VANGUARD VSD 71255, March.

STRAUSS, J. II: Waltz Transcriptions. Boston Symphony Chamber Players. DG 2530 977, Dec.

STRAUSS, R.: Songs. Te Kanawa, A. Davis.

COLUMBIA M 35140, Feb.

STRAVINSKY: Pulcinella. Abbado. DG 2531 087, Feb.

STRAVINSKY: The Wedding; Histoire du soldat. Levine. RCA ARL 1-3375, March.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Violin Concerto; Serenade melancolique. Perlman, Ormandy. ANGEL SZ 37640, March.

VL ADIMIR HOROWITZ: The Horowitz Concerts 1978-79. RCA ARL 1-3433, Jan.

GERARD SCHWARZ: The Sound of Trumpets. DELOS DMS 3002, Feb.

-------------------

... harpsichordists. The demands posed by the French Overture are rather different, of course, but Verlet's rhythmic impulse is no less gratifying. Welcome, too, is her marvelous way of shaping phrases, of accentuating climactic points and giving "breath" between them. That she is capable of great subtlety is richly revealed in the third of the four duets from Bach's Clavierubung, Part III. (Although this collection is expressly intended for organ, harpsichordists have losng laid claim to these curious duets; I suspect Bach would have been happy to have heard them on any contemporary keyboard instrument.)

In the Goldberg Variations these qualities go a long way toward avoiding the numbing monotony that can so easily ruin a performance, especially when, as here, all repeats are played. Verlet's interpretation is one of the finest I've heard, in fact, and-no mean compliment-I found it arresting from beginning to end. That said, it must be added that the very virtues of her general approach are sometimes exaggerated to grotesque extremes.

At the outset, her insistence on for ward motion prompts much too fast a tempo in the Aria, and in Variation 13 the character of the writing (evocative of the slow movement of an Italian violin concerto or even of a baroque operatic soliloquy) seems to imply a much slower basic pulse than it receives here; in Variation 15, more over, Verlet's rather hurried pace does not allow one to savor the poignant chromaticism. In the opening Aria and Variation 26, there is a tendency to rush toward the end of measures and a consequent distortion of rhythms. The application of inegaliti is generally tasteful, but I must confess serious reservations about the lurching, pointed inequality in Variations 23 and 29.1 am also bothered by occasional attacks of "hen peck" clipping of note values, as in Variations 4 and 22-and in the first movement of the Italian Concerto. My one other com plaint is with the performance (or splicing) of groups of variations as continuous movements, a perverse decision evidently intended to highlight the performer's conception of the work's structure; the effect is sometimes extremely jarring.

Apart from the last point, the flaws are small details in performances otherwise immensely enjoyable and admirably re corded. Both releases feature the same pleasant-sounding harpsichord: a 1976 Dowd-from the Paris workshop-d'apres Nicolas and Francois Blanchet, 1730. S.C.

BEETHOVEN: Sonatas for Violin and Piano (4).

Arthur Grumiaux, violin; Claudio Arrau, piano. PHILIPS 9500 055/220', $9.98 each. Tape: 7300 473'/784', $9.98 each cassette. Sonatas: No. 1, in D, Op. 12, No. 1; No. 5, in F, Op. 24 (Spring); No. 7, in C minor, Op. 30, No. 2'; No. 8, in G, Op. 30, No. 3',

A certain intangible quality in these recordings--the first of a projected set of the ten sonatas-augurs ill for this partnership of distinguished artists; apparently, the best one can hope for is a workable entente cordiale and, with luck, some flashes of inspired individual playing. Though there are no glaring ensemble lapses--the small ones are not necessarily fatal, as the successful collaborations of Szigeti /Schnabel, Morini/Firkusny, and Szeryng /Rubinstein demonstrate--neither is there any real meeting of minds.

After a long hiatus, Arrau seems to have lost the knack of playing true chamber music. Perhaps he never had that knack to the degree that Schnabel, Curzon, or Bauer did, but he certainly sounded more bodily involved in his Beethoven cycle with Szigeti (Vanguard Everyman SRV 300/3E).

He seems reluctant to take a commanding lead, preferring instead to be gruffly meditative. But he doesn't really follow, either, and his stout, rich, bass-oriented touch resolutely refuses to blend or support, just as his unspontaneous phrases and rubatos never quite mesh purposefully. Grumiaux, with his seamless, suavely produced tone, tries to soar, but his flights of fancy are held down by Arrau's sobriety like a butterfly pinned to a mounting board. (The Op. 24 Adagio is a perfect case in point.) Not one of these performances comes close to the songful ones Grumiaux once recorded with Clara Haskil, nor do they have the range and searching forward drive of the ones Arrau recorded with Szigeti. The D major and C minor fare passably well, but the G major is utterly depressing in its clumsiness; a more charmless reading of this ebullient piece would be hard to imagine.

Philips' sound, to make matters worse, makes it seem that each artist is playing in his own hermetically sealed vacuum-engineers' balance with a vengeance.

H.G.

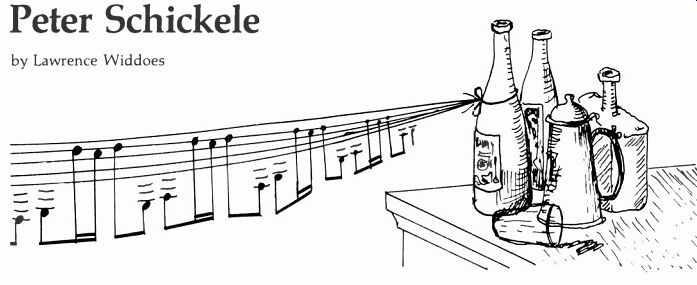

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 6, in F, Op. 68 (Pastoral). English Chamber Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas, cond. [Steven Epstein, prod.] COLUMBIA M 35169, $8.98. Tape: MT 35169, $8.98 (cassette).

This recording, billed as Vol. 1 of a Beethoven with Chamber Orchestra series, reduces the orchestral heft--which is to say, the string complement--to dimensions comparable to those of Beethoven's time and uses single woodwinds. Beethoven symphonies have been recorded by chamber orchestras before: Marriner gave us a few, and the Walter/Columbia Symphony and Scherchen /Vienna State Opera Orchestra performances suggest a cutback of personnel. But all of these accounts fudged the issue to some degree, Marriner's string tone beefed up with dubious reverb and Walter's and Scherchen's woodwind lines no more distinguishable than usual. In contrast to these mistaken attempts to simulate large-ensemble sonority, the present production wears its intimacy like a badge of honor.

One of the unexpected upshots is that, although the strings are fewer, more of the detail in their parts emerges from the tonal fabric: Divisi writing is far more telling than usual; dynamic inflections, such as the hairpin crescendos and diminuendos, make greater dramatic effect; ostinato and Alberti figurations come clearly to thefore; and when the double bass enters to rein force the cello line at climactic moments, the listener becomes more acutely aware of the entrance because of the spareness of the forces.

There are, however, some losses as well. For all the keenness of the smaller dynamic inflections, a few of the larger climaxes inevitably lack lung power; predict ably, the thunderstorm is disappointingly scrawny. Thomas has obvious affection for this genial music, and most of the playing is precise and admirably paced. Tempos are brisk, and rhythms are lean and kinetic.

Once or twice, particularly in the outer movements, the direction verges on precious affectation, but in the main this is a loving, intelligent, and well-recorded Pastoral.

-H.G.

BRAHMS: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, in D, Op. 77. Herman Krebbers, violin; Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bernard Haitink, cond. PHILIPS FESTIVO 6570 172, $6.98. Tape: 7310 172, $6.98 (cassette).

If your local orchestra presented its concertmaster in a warhorse violin concerto, would you trouble to attend, let alone buy it on a record? The Concertgebouw isn't just a local orchestra, of course, and Herman Krebbers can hold center stage very well. He plays Brahms with utterly luminescent tone, an aristocratic confidence in the face of technical hurdles, and a terraced shaping of phrases and dynamics that freshly confronts expressive meanings.

Even with modern tape splicing, many a superstar violinist has sounded less precisely on pitch (e.g., the exposed but utterly se cure landing on the stratospheric A at measure 348 of the first movement). In the Adagio, Krebbers dovetails with the wood wind choir as if he were playing chamber music with friends.

Haitink is of a mind with Krebbers all the way, and the warmth, richness, and freedom from distortion of Philips' mastering (this is not a reissue, but a first U.S. appearance of a fairly recent recording) are unexcelled.

------Michael Tilson Thomas A pared-down Pastoral.

Don't get me wrong. I'm not throwing out my Heifetz /Reiner (RCA LSC 1903) or Neveu/Dobrowen (late Forties EMI, never issued here) recordings, both of which feature a vehemence and propulsion far removed from the serene breadth and poise of Krebbers and Haitink. I also retain my attachment to the warmly idiosyncratic first Ferras recording with Schuricht (early London mono). But nothing in the recent lists (including Haitink's other recording with Szeryng, Philips 6500 530) has so refreshed my joy in this work. A.C.

BRUCH: Works for Violin and Orchestra. Salvatore Accardo, violin; Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, Kurt Masur, cond. PHILIPS 9500 589/ 90, $9.98 each. Tape: 7300 711/12, $9.98 each cassette.

Concerto No. 3, in D minor, Op. 58; Adagio appassionato, Op. 57; Romance, Op. 42. Serenade, Op. 75; In Memoriam, Op. 65.' This pair of discs-containing first recordings of almost all of this material completes the most extensive Bruch recording project ever, complementing the Accardo/Masur readings of the first two violin concertos (Philips 9500 422, March 1979) and the Scottish Fantasia and Op. 84 Konzertstuck (Philips 9500 423, August 1979). The newest installments may well be the most important of all, since the Third Concerto and the serenade prove to be vintage Bruch.

Though his Second Concerto seems a stale rewrite, the Third is every bit as good as the First. Like No. 1, it was written for Joseph Joachim, and its pugnacious opening chords make clear that it is to be a large-scaled, tough-minded composition as close to Brahms as Bruch ever came. To be sure, lyricism abounds, especially in the Adagio, but this work of 1890 shows that the composer had learned a thing or two in the twenty-two years that separate it from its hackneyed but lovable predecessor.

The character of the serenade, a very different work, also reflects the personality of its dedicatee. More sweetly introspective, it was composed in 1901 for Pablo Sarasate; Toscanini is reputed to have said that "Sarasate played like a lady." The shorter pieces are also quite lovely but are essentially sketches for the bigger essays.

A constant in the performances is excellent collaboration. Accardo's lean, pure style provides an excellent foil for this mostly somber music, and the dark, granitic orchestral backdrop (more forwardly miked than usual in this Philips /VEB Deutsche Schallplatten coproduction) gives strength and sentiment to what could easily sound merely turgid. H.G.

CAGE: The Seasons.

WUORINEN: Two-Part Symphony. American Composers Orchestra, Dennis Russell Davies, cond. [Carter Harman, prod.]

COMPOSERS RECORDINGS

SD 410, $7.95 [recorded in concert, December 11, 1978].

These works represent the tame sides of both composers. To John Cage, tameness came early and naturally-one might almost say prehistorically, since The Seasons predates his experimentations with chance, silence, notation, and noise.

Charles Wuorinen, on the other hand, has only recently discovered a docile side, and his move toward domestication has proved to be both a joy and a problem.

This novel direction makes Wuorinen's Two-Part Symphony the more interesting piece here, albeit not the more memorable one. Written in 1977-78, it might have been called Symphony in C or Short Symphony, but those titles had al ready been used, so the composer settled on Two-Part. The work is indeed in two parts, the second half prefaced by a slow section that could stand as an intervening middle movement. Had Wuorinen chosen to re-employ one of the other titles, how ever, it might have been even more significant, since his tendencies toward conventionality manifest themselves here in references, homages, and a distinct short age of imagination.

Nevertheless, when he notes that he had "a very good time" writing the piece, one can easily believe him. Gone is the sense one had so often with the early Wuorinen that he was trying hard to be erudite and esoteric; this music has a welcome flow and a feeling of inevitability that were not companions of his previous creations. Yet the symphony brings to mind several names, including those of Stravinsky and Bartok, but not that of Wuorinen. Understandable as it is that such a switch in style could cause an identity crisis, one must conclude that the newly tamed composer still hasn't found a way to purr differently from anyone else.

Cage, however, is a natural-born musical pussycat, and though he would undoubtedly fight the idea, his early contributions have turned out to be every bit as important and influential as his more outrageous ones. The Seasons, written thirty three years ago for the Ballet Society and dedicated to its director Lincoln Kirstein, has little to do with Vivaldi's famous work of the same name, but it is graphic, colorful, and, in the best old-fashioned sense of the word, charming.

Cage wrote, "The Seasons is an at tempt to express the traditional Indian view of the seasons as quiescence (winter), creation (spring), preservation (summer), and destruction (fall)." One might relate this to Wuorinen's use of the Greek cosmological word ylem ("that on which form has not yet been imposed") in connection with his symphony, but Cage's four seasons make up a mild, temperate landscape.

He relaxes in his summertime so convincingly that one wants to get out the hammock and the beer and loll away the warm afternoon. Fall and its "destruction" come with the heavy march of determined soldiers, yet even this cold onslaught isn't particularly threatening. There are other theoretical and numerological bases to The Seasons, but frankly they don't matter. A third of a century after its premiere, the work has a delightful, almost pacifying effect.

Both works are performed by the American Composers Orchestra, con ducted by Dennis Russell Davies, for whom the Wuorinen symphony was writ ten. This ensemble could undoubtedly play Beethoven quite wonderfully, but the point is that it plays new music extraordinarily well, and that's more than enough reason for its continuing to thrive. K.M.

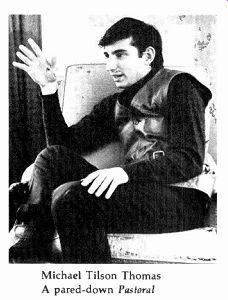

------ Anthony di Bonaventura Pianism that's a joy to the ear.

CHOPIN: Sonata for Piano, No. 3, in B minor, Op. 58. PROKOFIEV: Sonata for Piano, No. 7, in B flat, Op. 83.

Anthony di Bonaventura, piano. [Marc Aubort, prod.] ULTRA Fi ULDD 13, $9.98 (distributed by Sine Qua Non Productions Ltd., 25 Mill St., Providence, R.I. 02904).

This fine-sounding recording is confusingly billed as "Ultra Fi-direct disc-digital-high technology tape," and a column on the back of the jacket discusses the assets and limitations of all these methods, implying that all are indeed used here. Not so: This is, in fact, an analog product, whose only departures from the norm are high speed (30 ips) tape mastering and (apparently) careful processing and pressing.

Which goes a long way toward confirming my nagging suspicion that the real reason audiophile products sound better is that more care is lavished on their production, not because of any intrinsic superiority in the method of capturing live sound.

If anyone can deliver note-perfect performances without benefit of retakes and splices, Di Bonaventura can. Years ago, I heard him do just that in a recital performance of Chopin's B minor Sonata. His re corded performance, presumably edited, is equally poised but considerably riper and more interesting. Without being in the least eccentric, the rendition abounds in noteworthy details. Di Bonaventura ob serves the exposition repeat in the first movement, as do Argerich and Weissen berg but, to my knowledge, no other artists.

He has an acute ear for inner voice detail, without its being obtrusive. He is a master at shifting gears and characterizing phrases without in any way departing from modern practice or violating the longer line; the sense of continuity is far stronger, for ex ample, than in Ashkenazy's recent London version (CS 7030, February 1979), cultivated and well played though that was.

Throughout, the purling passagework is a joy to the ear-and a perpetual source of despair, undoubtedly, to any rival practitioner.

The annotation states that Di Bonaventura made the first American recording of Prokofiev's Seventh Sonata, but I can find no evidence to disprove my belief that Horowitz claims that distinction. In any event, the present account, slightly under stated but very spry and transparent, is more akin to the linear Richter interpretation (Turnabout TV 34359) than to the more massive and heroic readings of Horowitz (RCA ARM 1-2952) and Gould. Again, the pianistic finish is most impressive; only a bona fide virtuoso could clarify the onslaught of the finale to such as degree with out sacrificing headlong momentum. The piano tone is a bit spikier on the second side, which contains the Prokofiev and the last movement of the Chopin, but the sound of this excellent release remains of demonstration caliber. H.G.

DEBUSSY: La Mer. SCRIABIN: Poem of Ecstasy, Op. 54. , Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.] LONDON CS 7129, $8.98.

Once again, the Clevelanders seem the ideal Debussy orchestra, playing with bejeweled tonal delicacy, millisecond exactitude of ensemble, and superhuman control. Maazel combines the virtues of previous Cleveland Orchestra recordings of La Mer, the surging impetuosity of Rodizinski's old 78 (variously transferred to LP) and the meticulous precision and transparency of Szell's (Odyssey Y 31928). Maazel's use of rhythmic distensions for emphasis is less problematic here than in his last Debussy recording (London CS 7128, November 1979).

London captures the vertical strands of La Mer as well as it did for Solti and the Chicago Symphony (CS 7033, August 1977). Notwithstanding my earlier praise for that version, upon rehearing it, I find the Mack truck power of the Chicagoans over bearing compared to the Alpha Romeo sportiness of the Clevelanders. Maazel's taut, brisk reading joins a select group that includes Ansermet (London, deleted), Boulez (Columbia MS 7361), and Haitink (Philips 9500 359).

Unlike La Mer, which can stand diversity and repetition, Scriabin's Poem of Ecstasy doesn't wear well. I continue to find it loud, over-orchestrated, and redundant, though I warm to the artistry of Stokowski (London Phase-4 SPC 21117) and admire the sanity and lucidity of Abbado (DG 2530 137). Maazel, less analytic about solo high lightings, has one decisive advantage: That tiresome, fatuous trumpet tune is played with minimal vibrato and portamento. A.C.

DEBUSSY: Pelleas et Melisande.

CAST: Melisande Frederica von Stade (s) Yniold Christiane Barbaux (s) Genevieve Nadine Denize (ms) Pelleas Richard Stilwell (b) Golaud Jose van Dam (b) Arkel Ruggero Raimondi (bs) A Shepherd/ The Doctor Pascal Thomas (bs) Chorus of the Deutsche Oper, Berlin, Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Michel Glotz, prod.] ANGEL SZCX 3885, $27.94 (three discs, automatic sequence).

COMPARISON:

Soderstrom, Shirley/ Boulez Col. M3 30119

To quickly characterize this new Pellias: It is on the whole mellifluously sung by a cast whose voices and musical approaches share a general softness of attack and shadiness of timbre, thus according well with the homogeneity of orchestral sound obtained by the conductor. It is a thoroughly musical performance, by which I mean that it leaves the impression of a concert rendition, rather than a stage performance. Since its conductor is a strong-minded one in command of his own expert orchestra and the cast carefully selected, the reading has some very beautiful and powerful things about it and takes an identifiable stance on the work-so it is a contribution.

The nature of the performance in spires thoughts that run in ironic little circles. Maurice Maeterlinck, at the time of Pelleas and the other Symbolist plays that established his early reputation, wanted an actorless theater, one in which human normality could not intrude upon the symbolic progress of mystic communication. Or, to put it in terms of his personal predicament, he created out of a need to express a very intense, very private psychic world whose reality depends on the consistency and specificity of its unlikeness to more ordinary perception, yet whose embodiment can be accomplished only through creation of a stage-world in which the elements (especially people) are not always going to be have according to the laws of that private…

------- Lorin Maazel Taut, brisk Debussy

…universe. Can't live with 'em, can't live without 'em-a problem felt by most play wrights, but the young Maeterlinck was an extreme case, and of course except for a very limited life in small theaters of the fin de-siècle Parisian avant-garde, these plays have remained largely objects of study rather than of performance.

Along happens young Debussy in search of a text that won't remind him of Wagner's. In a sense, his search parallels that of Maeterlinck: Let's have an opera without all that singing, to go along with this play without acting. This eagerness to eschew all the vocal forms of opera and all the developmental forms of Wagnerian music-drama, together with the peculiar appropriateness of the composer's harmonic language and timbral spectrum for the world of the play, is widely and properly understood as a vital portion of the composer's contribution to the opera.

But it is the practical, active effect of these attributes that accounts for the comparative workability of the opera (and I think "comparatively workable" is about the right designation) as opposed to the play. The musical language is more than suggestively shifty, it's sensually compel ling, like a long sense-memory exercise on the environment of the drama-its outer world, much more than the inner. Oddly, though the musical description is sensuous, and as surely of the recognizable, natural world as a Rossini or Verdi storm scene, it has the effect of persuading audiences that it is about Maeterlinck's mystical inner world, and that this world may be worth entering. In fact, it appears to be more about the realms of light and beauty to which the characters' souls dimly aspire than about the fleshly purgatory to which dualistic mysticism has us condemned, and which is such a powerful deterrent to audience sympathy.

And all this non-singing, which is in operatic terms so mysteriously subtle and reticent, and seems to leave so much unexpressed, is upon examination just what Debussy intended it to be-a step toward a more realistic, dramatically justified mode of musical expression, by means of which the vocal line transcends our more normal forms of discourse by relatively minor degrees, and only in response to urgencies for which words will not suffice. (Debussy de fined the necessity of singing in opera in virtually the same words as did Walter Felsenstein.) Naturally, this has the effect of magnifying, not reducing, the performer's role, of giving him more of the ammunition Maeterlinck would like to have taken from him.

So here is Debussy, giving to Maeterlinck's play generous measure of all the qualities the author would like to have kept out and, since these are precisely the ingredients needed to give the play performance life, lending the author his one continuing claim to theatrical attention.

And here further is Von Karajan, who in principle would appear to agree with Maeterlinck. That is (and this is the reason actors are so inconvenient), the characters are seen as beings whose consciousness does not contact the true reality, carrying on an unwitting struggle against forces that remain undefined. To act, to choose, is to assume a responsibility and freedom that destroy the reality of such a world. Marionettes are the perfect actors, and they are just what Maeterlinck wanted.

Herr v.K. is the perfect interpreter, not of Debussy, but of Maeterlinck. But of course whereas Maeterlinck's characters wandered through the castles and forests of his inner world, slaves to his psychic needs like Pirandello's six characters and controllable while unperformed, Karajan's singers are selected musical instruments that prowl amongst the shadowy glades and thickets of the Berlin Philharmonic, quite incapable of actions that do not accord with the master plan of the Higher. This is surely not what Maeterlinck had in mind (it was he who was to supervise the characters' fates), and as to whether Destiny should be named Maurice or Herbert, I wish we could drop in on that one, fortified with the amused program note I imagine Debussy would provide.

Maeterlinck's dream theater is evoked by any recording, for in this medium we are at last rid of the damned per formers. True, they leave their scent. We track them through the grooves with styli

sharpened and drawn, and if we're experienced hunters, a glimpse of the spoor is enough to conjure a magnificent vision of the beast. A whopper he always is, powerful and quick and alert, caught at the stretch of some mortal action in a lush or dizzying locale.

So how sobering it generally is when, thirty-dollar pasteboard in hand, we corner the prey at last and discover an entirely ordinary, vulnerable creature with a slight limp and a puny horn, exhaustedly foraging at the bottom of a gully amid the weeds and tin cans and beer bottles. Is this Alaska yet? No, it's only Mahogany. And we feel the force of Maeterlinck's wish, for surely our illusions are wonderful, and it's not easy to surrender them for realities of which the best that can be said is that they have a certain presence, a certain unpredictability, a certain potential for inter action-that they are, in short, realities. Be sides, we saw ourselves, bone-to-bone and steady in the sling, sending that single shot to the heart as he charged from the brake.

It's hard to admit that the real question is whether or not we can hit a motionless tar get at fifty yards, and that the recoil left our shoulder aching for a fortnight.

How gratifying it can be, with just a spin of the platter, to at once indulge our illusions and to put these animals exactly where Maeterlinck saw them, endlessly and blindly repeating their actions in patterns whose end already exists at the beginning; and moreover to choose either to be over come or to rise to the mastery of an objective view-a choice made much harder by the complexities of the theater. Karajan is truly an ally here, particularly if our wish is to be overcome and to experience, through the music, the Maeterlinckian notion that a half-apprehended environment (the orchestra) determines, absorbs, and eventually dominates every utterance of the individuals represented in the drama. The most obvious contrasts among recorded performances are with the Boulez and Desormiere (long deleted) recordings.

In the former, the textures are so much more opened out and exposed, and the musical gestures so precisely achieved, that they become easier to appreciate and understand on their individual terms rather than as ingredients of the whole. With our gain in understanding comes a diminishment of the ruling power of the mystery-that much is purely a question of taste or philosophy, not of quality. The elements of Boulez' environment are encouraged to lead their independent lives, and so are the characters themselves. Two of them (the Melisande of Soderstrom, the Pelleas of Shirley) are given by far their most individual, strongly colored representations on record--a fact I appreciate more thoroughly with the passage of time and repeated comparisons. The others are not, but that is through incompleteness of execution, and not through design.

------ Frederica von Stade An impeccably musical Melisande.

The Desormiere recording, whose age dictates a compression of orchestral sound and a simplicity of highlighting, pre serves an age when French opera (emphasis on both words, please) was actually per formed. The singers compel attention via their unfailing competence, their suitability for their roles, their easy stylistic agreement. The orchestra is firmly conducted by an experienced fellow who is content to be a master, not a Master.

We might say that Karajan's case against Debussy on behalf of the young Maeterlinck is fairly complete, for no other performance I've heard so mercilessly clarifies Debussy's connections with styles, both antecedent and descendant, he wouldn't have cared to be associated with.

Parsifal hits us in the face in the early interludes, Tristan in the late ones. And in many of the accompanimental and descriptive passages, especially those for muted strings, we're given a bath in '30s easy listening of the sort that was cribbed from Debussy and Ravel--you can see that blonde moderne furniture, V-neck cocktail dresses, lipstick on the cigarette butts, the whole picture. All defensible, of course, mostly beautifully played if you accept the cushioned attacks and phrasing (as opposed to the sharpness of Boulez with the Covent Garden orchestra), and carried through with consistence and proportion. The interludes become the high points of the performance (Destiny at length swallowing the kit and caboodle), and the late ones, along with the second fountain scene, have stupendous weight and intensity--I was almost put in mind of Furtwangler's Tristan, the Act II pages embracing the entrance of the hero. While Karajan does not secure (or, I assume, seek) the amazing rhythmic lucidity of Boulez, there are points where his more basic sense of rhythmic line pays off, as in the 6/4 tread ("Lourd et sombre") of the beginning of the vault scene.

The cast is superbly chosen to carry through the concept: lovely, genteel voices and temperaments, refined and sensitive musical minds. Contrast is minimized from the lyric "mezzo-soprano" of Von Stade's voice to the light high bass of Raimondi's is not a wide span, particularly with a baritone Pelleas and a soft-textured bass-baritone Golaud in the middle reaches. Von Stade's performance is beautifully intoned and impeccably musical.

Since on the one hand the role is low for a soprano and on the other Von Stade's timbre is by no stretch that of a mezzo but that of a medium-weight lyric soprano, the categorization is no problem at all. I am at times touched and charmed by her reading in the same way one is touched and charmed by a fine Debussy pianist. I am unable to derive from it the slightest definition of Melisande's feelings, actions, or traits, beyond unquestionable good taste and superb manners (qualities it seems most unlikely Melisande would possess) and an occasionally detectable tristesse.

Stilwell, a little more projective of personal qualities, employs his warm voice with the heady fluency of the true baryton Martin. I have come to a fairly clear preference for a tenor in this music-a voice like that of the young Jansen (on Desormiere) or the young Maurane (on Fournet, and both these artists recorded the role second times, for Cluytens and Ansermet, to lesser effect), or the darker, more metallic tenor of Shirley, makes the best case for the music and brings welcome touches of textural relief. But Stilwell solves the role with admirable ease, never letting the voice over weight or cloud up in the area of the break, and though like all baritones he is pressed by the tessitura of his final scene, he doesn't let it defeat him.

I find Van Dam a boring Golaud, despite good musicianship and quite lovely vocalism. The sound of the voice is always a pleasure, and with so few singers nowadays in command of the even gradation and well-bound legato that goes with his deeply tanned tone, perhaps we oughtn't look the gift horse in the mouth. But this is a long role, and one of tremendous opportunities.

Van Dam's assumption of it at the Met was, I thought, an uninformed walk-through, but it seemed unfair at the time to leap to any conclusion, since the house production goes all the way with M.M. and eliminates acting completely. Here, though, the story is the same-a nicely equalized, almost casual vocalization, invariably round and soft in attack regardless of intent, and a lack of core or bite in the inflection that seems as much an absence of dramatic will and imagination as of vocal method. At the awful emotional climaxes of the late scenes with Yniold and Melisande, he contributes only the most obvious indications. This is good singing, and possibly he is no more to be blamed than the others, but his role is the most severely damaged by such lacks, and comes up monotonous.

Raimondi seems an odd choice for Arkel, but in fact he has clearly made quite an effort to find a solution for the role. He has a reasonable musical affinity for the style, and employs a gently touched piano that does indeed sound at moments like a French your couverte. His opening scene is successful, and later, in the few moments where the singer of the role must open out, he has more to offer tonally than most. But in Acts IV and V, where the role has its sustained passages, his attempt to deal softly and inwardly with the declamation that lies persistently around B and C becomes too croonish and gummy. A piece of work one must respect, but only partly successful.

Nadine Denize, yet another mezzo with attractive tone that has no trace of depth or darkness, deals straightforwardly with Genevieve. Her reading of the letter falls a bit flat because of the lack of character in the sound (I see one review believes the mike placement was disadvantageous that's not how I hear it, but one way or an other you get the idea); she is fine when she sings out by the seashore. The Yniold is a grownup soprano (Christiane Barbaux), the solution I favor, and quite good. The doctor's pleasant voice is rather light, and it sounds as if he has been ordered to not sing too much.

The recording does not capture the detail or the small balances as well as Columbia's for Boulez. But it's not intended to, and it does contain the remarkable dynamic range inherent in the reading. The surfaces of my copy were not very clean.

Pelleas is an opera that has been well served on recordings. None of the seven LP performances is, on balance, a failure. This one offers a slant on the work that is not my preference. Maeterlinck was wrong. I want a conductor who understands and projects the piece in a more than purely musical sense, and performers with marked individual qualities and strong feelings for the personal situations of their characters. It's a shame that the rest of Boulez' cast is not on a level with his leads, and that Desormiere's could not have been recorded twenty years later. But if you were to own all three, you'd have the waterfront pretty well covered. C.L.O.

FERNEYHOUGH: Transit.

Rosemary Hardy, soprano; Linda Hurst and Elisabeth Harrison, mezzo-sopranos; Peter Hall, tenor; Brian Etheridge, baritone; Roderick Earle, bass; London Sinfonietta, Elgar Howarth, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.] DECCA HE ADLINE HE AD 18,

$9.98 (distributed by London Records).

The thirty-six-year-old English composer Brian Ferneyhough is fast establishing himself as one of the major composers of the younger generation. His output, already totaling some twenty published works, has attracted growing attention in the world press, particularly in England and Germany (where Ferneyhough re sides); Transit won the 1979 Koussevitzky International Record Award as the best new orchestral work to receive its premiere recording.

Transit, completed in 1975, is a com position of vast conception and extended length (about forty-five minutes) for six voices and chamber orchestra. According to the liner notes, its initial impetus was visual: "a pastiche of a Renaissance woodcut from a nineteenth-century work on popular meteorology depicting a philosopher, his right arm outstretched in a dramatic gesture, in the moment of penetrating the crystalline sphere, which in the Aristotelian cosmology separates the Earth from the higher spheres, thus glimpsing the workings of the cosmos." The composition effectively conveys the sense of this striking image in its truly cosmic conception of multiple levels of instrumental groups and voices positioned in a cyclic structure of breathtaking expansiveness.

There are twelve principal sections, each with its own distinct character and instrumental sound. Vocal sections alternate regularly with purely instrumental ones, the only exceptions being the last two, which are vocal and linked together to form a kind of climactic finale. The voices, used almost exclusively in ensemble (although there is a very brief bass solo near the end), intone texts from Paracelsus, Heraclitus, and the Corpus Hermeticum ("a collection of writings, supposedly by the mythical ancient Egyptian sage Hermes Trismegistus, identified in the sixteenth century as forgeries from the Hellenistic period"). The words, however, are fragmented into their syllabic constituents and are for the most part intended to be incomprehensible.

There are two basic, alternating types of instrumental music: "tuttis," relatively heavily scored, and "verses," more lightly orchestrated and featuring a solo woodwind (flute, clarinet, and oboe, respectively, in the three verses) in a concertante manner.

What most distinguishes Transit is how convincingly it moves through this sequence, communicating a sense of formal continuity and direction rather than seeming a mere series of isolated "movements." This accounts for at least one aspect of the title, as Ferneyhough consistently creates effective transitions from one segment to the next, so that one flows logically from the other despite its strongly contrasting character. The music itself is intensely personal and uncompromisingly serious.

Technically, it features an interesting combination of strict serial procedures and more intuitively conceived modifications.

Ferneyhough is especially accomplished at producing striking formations of timbre and texture that gradually change and be come extended formal developments. The result is music that always sounds up to date but is by no means unreasonably difficult to follow. Moreover, the listener feels that he is hearing something important.

This music communicates, no matter how difficult its message may be to decipher verbally.

Judging by this work, the first Ferneyhough composition I have heard, he has a remarkable gift for working with musical ideas of unusual scope and expressive power. His is clearly an important new voice. R.P.M.

HANDEL: Alexander's Feast.

Helen Donath and Sally Burgess, sopranos; Robert Tear, tenor; Thomas Allen, bass; King's College Choir (Cambridge), English Chamber Orchestra, Philip Ledger, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL SZB 3874, $17.96 (two discs, automatic sequence).

COMPARISON:

Harnoncourt/Vienna Con. Musicus Tel. 26.35440

In my recent encounter with Nikolaus Harnoncourt's recording of Handel's "oratorio" Alexander's Feast (May 1979), my delight in hearing this magnificent masterpiece overshadowed most of the reservations usually evoked by performances of the Concentus Musicus, with its weak orchestra of "original" instruments and a "leader" who apparently operates by remote control. Now there comes another recording, conducted by a knowledgeable professional presiding over a first-class modern orchestra.

The difference between the two versions is forcefully evident after a few measures of the fine overture: The violins are warm and expressive but never over powering, their pianos soft yet substantial; the attacks and releases are precise, the dynamic nuances delicate, and the balances superlative. The minuet that concludes the French overture reveals the elegant Handel, whom we so seldom encounter in performances. There is no comparison between this kind of altogether musical playing and the ideologically encumbered performance of the Harnoncourt ensemble, despite the latter's undoubted competence. Philip Ledger does not rigidly follow uncertain rhythmic laws, does not overdot, and keeps every thing clear and airy. The clarity, precision, and dynamic range proper to every occasion are maintained unfailingly.

So far my prayers are answered, but now the singers enter. The first soprano and the tenor occupy such prominent places in the unfolding of the work that they can make or ruin a performance. Here Harnoncourt has the edge, because Ledger's singers let us down. Helen Donath, a soprano favorably known, is not at her best; she has a nice voice, and she is an intelligent and fervent musician, but, at least in this recording, vocal control is missing. In quieter passages she does well, but most of the time her voice is tremulous; in fact, it wobbles almost to the extent of becoming an involuntary trill. On the other hand, her deliberate trills are poor. The tenor, Robert Tear, another singer widely known and well thought of, is equally unsatisfactory; in the fast passages he huffs a good deal, the vocalises do not seem to agree with him, and he has difficulties with low notes. Felicity Palmer and Anthony Rolfe Johnson, their counterparts in the Telefunken al bum, are solidly on pitch, comfortable vocally in all situations, and although perhaps a little mannered, distinctly superior to their competitors.

The less able Donath and Tear do, however, maintain a desirable heroic/dramatic tone. We must remember that in the center of Dryden's ode stands a triumphal campaign of Alexander the Great, with such other protagonists as Timotheus, a famous singer in antiquity, and Thais, the celebrated courtesan; the "gentle" St. Cecilia, to whom the work is dedicated, is dragged in rather peremptorily at the very end as a near non sequitur. Fortunately, the tone of the poem and the richness of Dryden's language were congenial to Handel, and there is never a weak spot in this score full of wonderful melodies.

The choruses in both recordings are excellently trained, but Harnoncourt's mixed chorus sounds better than the Cambridge body, which relies on boy trebles and altos. The latter are very good, they are on pitch, and there is no hooting. Compared with the Stockholm Bach Choir's luminous trebles and altos, however, their voices are colorless. Both versions fail to supply enough harmonic support for the arias accompanied by concertante violins (all violins in unison) and bass; since the bass is figured, the continuo is obviously counted upon to replenish such two-part settings to complete the harmony.

In sum, both of these recordings have advantages and disadvantages, and they are not interchangeable. So it comes down to whether you want good singing and are willing to take Harnoncourt's tepid historicism as part of the bargain, or whether you want a live, vibrant back ground and will tolerate somewhat flawed singing. P.H.L.

LISZT: Fantasia on Beethoven's Ruins of Athens-See Schubert-Liszt: Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra.

MAHLER: Symphonies (5); Sym phony No. 10: Adagio; Songs. For a review, see page 71.

MASSENET: Werther; Don Quichotte; Sapho. For a review, see page 67.

MENDELSSOHN: Symphonies: No. 4, in A, Op. 90 (Italian); No. 5, in D, Op. 107 (Reformation).

Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Leonard Bernstein, cond. [Gunther Breest and Hanno Rinke, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2531 097, $9.98. Tape: 3301 097, $9.98 (cassette) [recorded in concert].

COMPARISON--Italian: Muti/New Phil. Ang. S 37412 This is one of Leonard Bernstein's more unusual efforts, with many significant departures from his norm: strongly inflected readings that combine dynamic energy with lyric sentiment, a rather unsubtle orchestral timbre in which voices are nevertheless clearly defined and generally balanced, and a strong personal interpretive profile. Perhaps we are hearing a new Bernstein.

The strings have always been the Israel Philharmonic's strongest element, and they respond to Bernstein's lyrical line even more markedly than did the New York Philharmonic's in his earlier versions of these symphonies ( Columbia MS 7057, 7295). This is, I suspect, partly a matter of his own current stylistic concept, although one cannot rule out the possibility that he is responding sympathetically to the group's character.

The woodwinds and brass are distinctly inferior; except when spotlighted explicitly by Mendelssohn's scoring, they contribute little more than an amorphous background to the overall texture. Top and bottom predominate, without the detail and clarity Bernstein usually elicits. This may be due to the circumstances of live recording, circumstances beyond the conductor's immediate control. The acoustics of a well-filled hall, the effect of an audience on the performers, and a different recording team may all have contributed to a lighter, less forward sound, quite different from that which Bernstein has usually produced in his Columbia studio recordings with the New York Philharmonic. Yet he is a strong conductor, and if he is not here the energetically driving leader we have come to know so well, perhaps the difference does indicate a change in style. His infectious response to sentiment is better controlled than in the past-almost strangely introverted. His control of climax, so essential to his dramatic sense, is still evident, but the impact one expects from him isn't quite achieved.

Fascinating as this record is, it cannot receive unqualified recommendation be cause of the Israel Philharmonic's short comings. Bernstein fans may want to look into possible new facets of his approach, but they will probably prefer his earlier versions. The best account of the Italian is still Riccardo Muti's with the New Philharmonia, although for some the seduction of the wondrous digital sound of the Vienna Philharmonic under Christoph von Dohnanyi (London LDR 10003) may compensate for a rather dull performance. P.H.

MESSIAEN: Quatuor pour le fin du temps.

Luben Yordanoff, violin; Albert Tetard, cello; Claude Desurmont, clarinet; Daniel Barenboim, piano. [Gunther Breest, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2531 093, $9.98.

COMPARISON:

Tashi RCA ARL 1-1567 Symphony Chamber Players.

In the performance I heard that season by Silverstein, Eskin, Wright, and Kalish, Messiaen's transfigured vision of hope in the midst of desolation emitted a hypnotic radiance I have yet to encounter in any other interpretation.

Now DG has recorded this unique composition in Paris under the watchful eyes and ears of the composer, and that should count for something. Indeed, balances are impressive, and most of the tem pos are very close to the metronome markings. An exception is the sixth section, "Dance of Fury, for Seven Trumpets," understandably below snuff, given its trickily syncopated unison writing.

The players work efficiently together, but limitations appear where individual contributions come to the fore. Tetard's slow vibrato becomes nerve-racking in "Praise to the Eternity of Jesus." At cue D in the final "Praise to the Immortality of Jesus," Yordanoff's landing on the G string sounds more syrupy than seraphic, while Barenboim's pianism is disconcertingly violent in the repetitive chord patterns of thirty-second notes followed by double dotted eighths. Compare Peter Serkin in the Tashi performance: so coiled in rhythm, so terraced in the use of diminuendos. In the unaccompanied clarinet section, "Abyss of the Birds," Desurmont manages the one-measure swells from ppp to ffff nearly as smoothly as Tashi's Richard Stoltzman, but he also steals breaths and makes minor rhythmic errors.

Overall, the flaws of this new recording don't counteract its virtues, including of course that clear, rich DG recording job. I'd recommend it over the serviceable Gruenberg/Pleeth /De Peyer/Beroff version (Angel S 36587) or the somewhat rough and unsubtle Cohen/ Eddy /Rabbai/ Levin re cording (Candide CE 31050), despite the latter's moderate price and inclusion of a filler (Merle noir, for flute and piano).

Among commercial recordings, though, pride of place goes to Tashi, a group whose charter membership was defined by the unique scoring of this work; it repays the favor with playing of uncanny virtuosity, control, and musical acumen. A.C.

MOZART: Requiem, K. 626. Helen Donath, soprano; Christa Ludwig, alto; Robert Tear, tenor; Robert Lloyd, bass; Philharmonia Chorus and. Orchestra, Carlo Maria Giulini, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL SZ 37600, $8.98.

So they are at it again, but the result is once more disappointing. Mozart's Requiem exacts a regrettable toll. It must be In 1972, DG missed a golden opportunity to record this work with the Boston the lack of rapport with that curious stylistic merger of the music of church and theater in the orchestral Mass of the eighteenth century, baffling to both musicians and churchmen ever since the Romantic era, that accounts for the dearth of really fine performances of this much-admired classic. The stylistic blend is even more problematic in Mozart's case because his Requiem is both highly personal and severely liturgical in spirit.

Still, a good musician, and especially an Italian, should find his way on purely musical grounds, and it is surprising that a conductor of Carlo Maria Giulini's stature should not have fulfilled our hopes-but then, he is in good company. In his defense, I must say at the outset that Angel's very poor sound must have thwarted his intentions; the excellent chorus in particular falls victim to faulty engineering. Nevertheless, there are things here that must be laid straight at Giulini's door.

While the great fugue and several other fast numbers move at a good clip, some tempos rival Klemperer's. The "Rex tremendae" is very slow, as is the "Record are"-those fine soloists gasp a little in order to breathe at the right places-and that ineffable choral song, the "Hostias," is down right funereal. The even flow of counter point in such places as the Introit is hampered by too much emphasis on down beats; the conductor apparently fails to realize that Mozart deliberately opposed the stile antico ("Requiem aeternam dona eis, Domine") to the modern rhythmic homophony ("et lux perpetua"). This texture is quite different from such latter-day counterpoint as the heavily accented fugal "Quam olim Abrahae." There are a number of such contrasts in the work, and they are not brought out. Nor is the even more subtle simultaneous employment of pared-down operatic accompaniment and almost Palestrinian polyphony, as in the otherworldly "Oro supplex," perhaps the most gripping passage in the Requiem.

The attacks are sometimes lazy, with basses and timpani the main offenders; the trombones are all over the place, though by now it is pretty well agreed that with a fully staffed chorus no colla parte playing is necessary, and the trombones should be restricted to obbligato passages, which are not difficult to locate. So we must consign this recording to the ranks of the many also-rans that offer decent enough performances of the score without touching on the mysterious depths of this last testament of a genius already in sight of the Elysian Fields.

A brief postscript: Almost all recordings of musical settings of the Mass proceed from number to number either with out pause or, at best, with a very slight one, even shorter than the rests observed be tween movements of a symphony. In this case, the recording launches the tremendous "Dies Irae" instantly after the Kyrie, which is disconcerting and blunts its explosive force. The liturgy prescribes several chanted prayers or readings between the two, as indeed between some of the other pieces, and the composer counted upon this separation. The "Dies Irae" would sound really apocalyptic if the shattering empty fifth that closes the Kyrie were permitted to evaporate from conscious ness. P.H.L.

PROKOFIEV: Sonata for Piano, No. 7, in B flat, Op. 83-See Chopin: Sonata for Piano, No. 3, in B minor, Op. 58.

SAINT-SAENS: Samson et Dalila.

CAST: Dalila Elena Obraztsova (ms)

----------

Samson Placido Domingo (t) Messenger Gerard Friedmann (t) First Philistine Constantin Zaharia (t) High Priest Renato Bruson (b) Abimelech Pierre Thau (bs) An Old Hebrew Robert Lloyd (bs) Second Philistine Michel Hubert (bs) Chorus of the Orchestre de Paris Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim cond. [Gunther Breest and Michael Horwath, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 095, $29.94 (three discs, manual sequence) Tape: 3371 050, $29.94 (three cassettes).

COMPARISON: Gorr, Vickers, Blanc/ Pretre Ang. S 3639

--------------------

This brings to three the number of complete recordings of Saint-Saens's most famous opera-hardly his only one-currently available. All are worthy performances, although in the final analysis the choice is between the earliest (1963) on An gel and the latest. This performance very much centers around Daniel Barenboim's warm and vibrant conception, spaciously recorded, but choice will ultimately depend on one's reactions to the Dalila of Elena Obraztsova.

Samson et Dalila has often been "condemned" as an oratorio masquerading as opera-a charge that has some foundation but does not hold up if one equates "oratorio" with "anti-dramatic." The opera works musically, and it works on-stage; it always has, and I suspect it always will. Its oratorio overtones serve to channel Saint Saens's romanticism into a solid structure that is not static, but dynamic. Samson's character development, from leader of the oppressed through enslavement, lust, downfall, and enlightenment in blindness (the mill scene of Act III, perhaps Saint Saens's greatest dramatic writing) to the anguish and conviction of the final scene, pro vides the impetus for the drama. That character is superbly drawn, and its strength allows the more celebrated pages of the score to assume their proper significance: colorful, varied, musically ravishing, but dramatically secondary to Samson's plight.

That said, it must be noted that Barenboim's conception, although always dramatic, moves the work closer to oratorio than to opera. He adopts a leisurely pace throughout, emphasizing the sheerly sensuous aspects of the writing through phrasing and ritards. His excellent large chorus follows his lead very well but sounds more like an ordinary chorus than like an opera chorus. Its soft-grained singing in the first scene is quite beautiful, but that is its fault: It is simply too comfortable to convey the idea of a populace crushed by misery and oppression, yearning for salvation. The yoke is too easy. Similarly, the last scene does not have the measure of fevered hysteria that delineates the Philistines in their wanton revelry before the disaster.

Placido Domingo's entrance ("A rre tez, o mes freres!") is treated lyrically rather than as an expression of frustrated rage (compare it to Jon Vickers' hammer stroke), and his view of Samson is presented throughout from a lyric rather than a dramatic point of view. This can be justified if there is a consequent enlightenment in the third act, but I never felt anguish in Domingo's mill scene, and his final scene seemed outside the character rather than at one with it, as it must be. Domingo's lesser attention to firmness of vocal line and accuracy of note values adds to this more generalized treatment of Samson, one that robs the hero of his rightful stature.

Obraztsova is even more of a problem.

On-stage the deficiencies of her large and romantic mezzo-a constant vibrato, an erratic equalization, a "covered" sound, as though sung into a brass cistern-are mitigated and even take on an intriguing individuality. But on records these faults are magnified and obscure her very real attention to sonority and characterization. She tries to compensate (as she does on-stage) by adopting a tigerish intensity, and this can be thrilling. Yet here, at Barenboim's slow tempos, and given her general indifference to legato (which is, as with so much French opera, of paramount importance), the declamatory outbursts stick out uncomfortably. Since records rob her of her considerable visual assets as an actress, her performance, conscientious as it is, lacks the unity it possesses on-stage and tends to dissolve into isolated moments.

Renato Bruson makes a dry-voiced High Priest, a bit uncomfortable in his French but nonetheless properly hectoring and implacable. The supporting cast is un remarkable, except for Robert Lloyd's well-sung Aged Hebrew.

Good, then, but not great. Its main competition, however, is close to being great. I have always felt that the Angel version stands as one of the finer opera recordings made-if not on the first list, certainly on the second. Rita Gorr, at the height of her vocal eminence in 1963, is a simply magnificent Dalila. Her vocal clarity and firmness are a joy, as are her attention to the vocal line and the variety of inflection she brings to it. One might want a bit more plushness and sexuality, but this is first rate operatic singing. Ernest Blanc, if again a dry-voiced High Priest, is likewise excel lent; the language is at the constant service of the music, and the conception is fully dramatic.

Vickers' Samson is, admittedly, rough-edged: not by any means letter-perfect in French, given to his trademarked (but at this stage still incipient) croon in softer passages, and generally declamatory.

But, grand Dieu! This is a Samson-a leader of his people-whose animal vitality leads inexorably to his enslavement and enlightenment. Vickers has rendered the final act better since 1963, but even then it was in fused with the spirit demanded by the text and the music. His Samson eclipses Domingo's, despite the latter's greater lyric gifts.

Georges Pretre's conducting career has been uneven, but from the start he has had a strong rapport with this score. His leadership-leaner, more propulsive, and more rhythmically alive than Barenboim's, yet luscious enough when the occasion warrants-is closer to the spirit and drama of the work, even though Barenboim brings out felicities that Pretre does not.

The RCA recording (ARL 3-0662) is not in a class with either of these. James King sings a constricted, effortful Samson, Bernd Weikl is an acceptable High Priest, and Giuseppe Patane's conducting is little better than routine. Its calling card is the Dalila of Christa Ludwig, sung with appro priate sensuousness, yet always dramatic.

But Ludwig, alas, cannot carry the show. P.J.S.

SCHICKELE: The Knight of the Burning Pestle: Songs (9); Elegies; Summer Trio. For a featurette, see page 76.

SCHUBERT: Sonata for Piano, in B flat, D. 960. Lili Kraus, piano. VANGUARD VSD 71267, $7.98.

This just misses being a great performance. Never one to underplay, Kraus sees not only dreamy, drawn-out lyricism in this sonata, but also drama and tension.

To express them, she inserts subito fortes, changes a dynamic from ppp to a hefty mezzo forte, stresses the big line at the expense of minute rhythmic detail, and favors explosive vehemence.

As applied to Schubert's companion opus, the A major Sonata, D. 959 (long a Kraus specialty, which Vanguard should invite her to re-record), her willfulness and vitality seem appropriate and even riveting, but the longer-breathed B flat Sonata needs a more patient, less brusque treatment. The "excitement" seems artificial; after once being startled by Kraus's pouncing and driving, I longed for a wider range of color and a more beautiful sonority. Still, she is always interesting and often splendid, particularly in her heroic reading of the Andante sostenuto. This is easily one of the finest recordings of the work.

Vanguard's sound is adequate with out being especially luminous or sonorous.

The review copy had somewhat noisy surfaces and a little warpage. H.G.

SCHUBERT-LISZT: Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra, in C, D. 760 (Wanderer). SCHUMANN: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, in A minor, Op. 54.

Ilan Rogoff, piano; Philharmonia Orchestra, Kurt Sanderling, cond. [Anthony Hodgson, prod.] UNICORN RHS 367, $10.98 (distributed by Euroclass Record Distributors, Ltd., 155 Avenue of the Americas, New York, N.Y. 10013).

SCHUBERT-LISZT: Fantasia for Piano and Orchestra, in C, D. 760 (Wanderer). WEBER-LISZT: Polonaise brillante, in E, Op. 72 (L'Hilarite). LISZT: Fantasia on Beethoven's Ruins of Athens.

B Jerome Rose, piano; Philharmonia Hungarica, Richard Kapp, cond. TURN ABOUT QTV 34708, $4.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

For the most part, Liszt's ministrations on behalf of other composers fall into two categories: fairly straight arrangements of orchestral and instrumental works for piano and more freely inspired piano paraphrases from operas. Of course, the boundaries are sometimes blurred, as in the six Transcendental Etudes After Paganini, where masterly violin writing is trans formed into equally brilliant and idiomatic piano writing.