by Susan Thiemann Sommer

IF YOU DON'T already own a recording of this superb path-breaking opera, you will probably want to after hearing Telefunken's brilliant new edition. Although billed as the first complete version with authentic instruments, Harnoncourt's approach is very similar to both August Wenzinger's fine Archive recording of some years ago (now deleted) and the recent Musical Heritage release conducted by Michel Corboz. All three performances share a restrained interpretation with proper respect for Monteverdi's orchestration and sparing use of ornamentation. Telefunken and Archive rejoice in magnificent casts, perfectly equipped to handle both the musical and dramatic demands of a comparatively unfamiliar style; Musical Heritage's weaker casting is compensated by the thrilling Orfeo of Eric Tappy. After carefully listening to the three versions, however, I would give Telefunken the edge in most details.

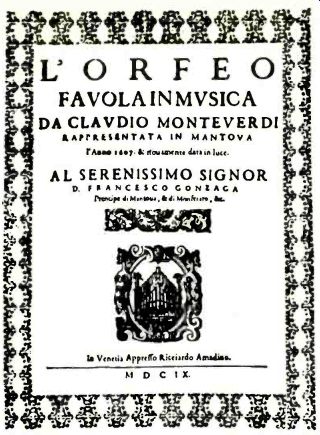

When one considers Orfeo's tautly constructed plot, the myriad forms of musical expression, the flexible rhythms and jarring harmonies which underline the dramatic and emotional meaning of the text. it seems impossible that Monteverdi had virtually no models to draw on as he framed this new musico-dramatic form. True, he used the musical language of his day, but Orfeo is light years from its nearest rival, Jacopo Peri's musically constructed setting of Euridice. It is a measure of Monteverdi's achievement that, with over 350 years of later operas sounding in one's ears, one can and does compare Orfeo with the best of them. Even the one missing ingredient--the great melodic sweep familiar to us from Verdi, Mozart, and Puccini, and which Monteverdi himself introduced in the melting lyricism of his later operas--is here in a nascent form.

You may hear it in the ritornellos and especially in Orfeo's two songs, "Vi ricordi o boschi ombrosi" with its lilting triple meter and closed form, and the exuberant "Quale onor di to fia degno," where Orfeo, overjoyed at regaining Euridice, breaks into an enthusiastic melody of a distinctly Verdian cast.

The great moments in the opera are the dramatic ones-the arrival of the messenger in the midst of the wedding celebrations with news of Euridice's death; Orfeo's bitter grief and the despair of "Tu se' morta"; and, one of the most touching moments in all opera, Euridice's cry "Ahi vista troppo dolce," when Orfeo looks back at her and loses his wife forever.

The big role of course is Orfeo, who is on stage for almost the entire opera and sings over half the music in the last three acts. The vocal range of the part is rather narrow (about an octave and a half), and the tessitura is often quite low. It is natural, therefore, to assign Orfeo to a baritone. Lajos Kozma is a tenor, and closer, I think, to the quality that Monteverdi probably had in mind for the role. The middle and lower parts of his voice are firm: the top opens out into a ringing head tone that makes phrases like Orfeo's final plea to Charon, "Ahi sventurato amante," particularly exciting. Although Kozma lacks the passion of Eric Tappy's Orfeo, the robust quality of his voice suggests a more virile hero. In moments of dramatic intensity Kozma gives a little extra bite to his consonants and shades his lines slightly more dramatically than Helmut Krebs on the Archive version, though neither singer really explores the full emotional potential of the role. Kozma is at his very best in the bravura showpiece "Possente spirto," and copes brilliantly with each florid, rhapsodic strophe. His performance captures something of the spirit that must have kept the Mantuan and Florentine courts spellbound when a Caccini or a Peri sang.

The other roles are equally well cast and match or surpass their counterparts on Archive (Musical Heritage doesn't even compete in this department). Three ladies share six female roles and it is fascinating to see how each of them has managed to differentiate the separate characters. Cathy Berberian plays the Messenger not as a god-sent herald of doom but as a shy and hesitant girl overcome with the bad news she must bring Orfeo. A shepherd does describe her as "gentle Sylvia," one of Euridice's girl friends, but I had never suspected this human side to her character before. As Speranza, Miss Berberian is somewhat more majestic, as befits this allegorical personage. Eiko Katanosaka convinces as both a light soprano soubrette (La Ninfa) and a warm-voiced mezzo (Proserpina), while Rotraud Hansmann's touching humanity as the luckless Euridice is in sharp contrast to her impersonal La Musica of the prologue. Charon and Pluto are splendid in their infernal roles. That both Archive and Telefunken could find basses to cope with the tessitura of Charon's part is extraordinary--that they are both so good is a miracle.

Monteverdi was quite careful in describing the constituency and use of the large, diverse orchestra available to him in Mantua for the first performance in 1607. Festival productions in princely courts regularly featured a great variety of instruments and the most famous virtuosos in Italy had been summoned for this occasion. Monteverdi divided the ensemble into two choirs to symbolize the realms of the earthly (strings and recorders) and the infernal (trombones and cornettos). Continuo instruments were chosen both for variety and their suitability as accompaniment for particular characters. The low buzzing of the regal, for example, perfectly conjures up the menacing figure of Charon. Harnoncourt assigns most of Orfeo's accompaniment to the harp, a happy choice musically as well as symbolically since the broken chords on the harp contrast nicely with the stolid progressions of the little organ, another stalwart of the continuo section. Telefunken's stereo layout sets earth and its representatives on the left, the underworld and its inhabitants on the right, an arrangement that further enhances these instrumental contrasts. As we have come to expect, Harnoncourt's ensemble is superb. The string tone in particular is outstanding: soft yet clear, producing a chamberlike ambience wholly appropriate to a work that was originally intended for performance in a very small hall. The recorded sound, I should mention, is glorious.

Like Wenzinger and Corboz, Harnoncourt is cautious if not downright ascetic in his application of vocal ornamentation.

The conductor argues in the liner notes that since Monteverdi went to the trouble of writing out what decoration he wanted (in some places), he obviously didn't want anything further added. Yet the contrast between the spots where the composer did specify particular embellishments and the great bald patches where he did not, strongly suggests to me that he expected some sort of cadential ornamentation but wasn't especially concerned about which of the standard formulas the singers elected to use. Moreover it seems like a waste of a splendid opportunity, given the extraordinary abilities of the cast. Cathy Berberian's trillo (a trill not on two notes but on one) is absolutely perfect; I long to hear it more often.

Harnoncourt's second argument against ornamentation is equally familiar but, I suspect, more treacherous. "In our opinion," he says, "embellishment should be applied even more sparingly in a recording since every improvisation is fundamentally something unique which, when heard again ... becomes ridiculous." Surely discreet cadential formulas and expressive trills are no more ridiculous than the extravagant ornaments Monteverdi wrote out for "Possente spirto." What underlies Harnoncourt's statement, however, is the assumption that a recording is not a performance caught as it might exist in time, but a ponderously authoritative permanent record. This dangerous approach could lead to some pretty deadly results--I foresee Rameau and Couperin without ornaments, expressionless Chopin played without rubato, the Art of Fugue on a computer-all to preserve the purity of the text.

Telefunken has assigned each of the five acts to one side, and instead of filling out Side 6 with an appropriate selection of madrigals, songs, or dances, we are given a lecture in German on the instrumentation chosen for the performance. This is fine for practicing your German-Harnoncourt speaks slowly and clearly and is much easier to understand than I had expected--but still rather redundant since most of the information is available in the excellent notes.

MONTEVERDI: Orfeo. Rotraud Hansmann (s), Euridice and La Musica; Eiko Katanosaka (s), Proserpina and La Ninfa; Cathy Berberian (ms), Messaggiera and La Speranza; Lajos Kozma (t), Orfeo; Nigel Rogers (t), Pastor 2 and Spirito 1; Kurt Equiluz (t), Pastor 3 and Spirito 2; Günther Theuring (ct), Pastor 1; Max van Egmond (b), Apollo, Pastor 4, and Spirito 3; Nikolaus Simkowsky (bs), Caronte; Jacques Villisech (bs), Plutone; Capella Antiqua; Concentus Musicus, Nikolaus Harnoncourt. cond. Telefunken SKH 21, $17.85 (three discs).

-------------

(High Fidelity)

Also see: Classical Records Review ( Apr. 1977)-- Marriner's Messiah, Davis' Dvorak, etc.