reviewed by:

- ROYAL S BROWN

- ABRAM CHIPMAN

- R. D. DARRELL

- PETER G DAVIS

- SHIRLEY FLEMING

- ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN

- KENNETH FURIE

- HARRIS GOLDSMITH

- DAVID HAMILTON

- DALE S. HARRIS

- PHILIP HART

- PAUL HENRY LANG

- ROBERT LONG

- IRVING LOWENS

- ROBERT C. MARSH

- ROBERT P. MORGAN

- JEREMY NOBLE

- CONRAD L. OSBORNE

- ANDREW PORTER

- H. C. ROBBINS

- LANDON HAROLD

- A. RODGERS PATRICK

- J. SMITH

- SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

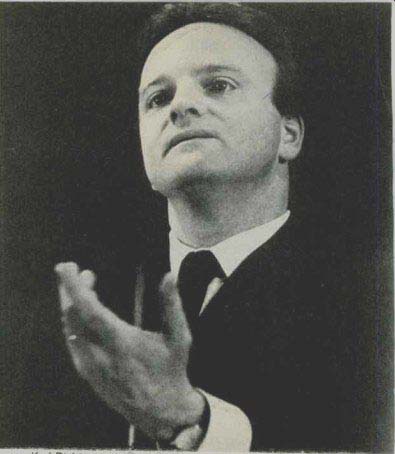

-------- Karl Richter-sometimes lively, sometimes leaden Bach

===========

Explanation of symbols:

Classical:

[B] Budget

[H] Historical

[R] Reissue

Recorded tape:

[O] Open Reel

[8] 8-Track Cartridge

[C] Cassette

==========

BACH, C.P.E.: Trio Sonatas: in B minor, W. 143; in C, W. 147; in B flat, W. 161. Eugenia Zukerman, flute; Pinchas Zukerman, violin; Samuel Sanders, harpsichord; Timothy Eddy, cello. [Thomas Frost, prod.] COLUMBIA M 34216, $6.98.

In his emulation of Menuhin's breadth of musical interests, Pinchas Zukerman is exceptional among today's young superstar fiddlers both for his repertorial catholicity and for his readiness to shift roles from violinist to violist, from soloist to conductor, from virtuoso soloist to chamber ensemblist. No doubt his relish for shared concertizing and recording has been strengthened by the ability of his flutist wife to join him as she already has in three earlier Columbia releases. Eugenia Zukerman is versatile too, doubling as jacket annotator for many of her husband's or their joint programs. In deed she does so again for the present batch of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach's trio sonatas. none of which is otherwise listed in Schwann, although W. 143 and 147 can be had on Supraphon 1 11 0640 (with two more trio sonatas, W. 145 and 148), W. 161 on MHS 971.

Since the two early works, W. 143 and 147, are merely pleasant, superficial examples of routine rococo music-making in which the flute and violin parts dominate, the relative reticence of the continuo players is not unjustified. But they are only slightly more outspoken in the W. 161 of 1751, which approaches more closely the nature of the classical-era trio. And in all three works the ensemble is further unbalanced both by the violinist's excessively polite deference to the flutist and by the lack of meld between his elegantly fine-spun string tone and her cooler, less polished wind tonal qualities. In the bright and clean, if lightweight, recording of these generally spirited performances, an occasional over-intense high-register flute note stands out jarringly. R.D.D.

BACH: Cantatas. Edith Mathis, soprano'; Anna Reynolds, mezzo2; Peter Schreier, tenor; Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone'; Theo Adam, bass-baritone': Munich Bach Choir and Orchestra, Karl Richter, cond. [Gerd Ploebsch, prod.] ARCHIV 2533 313. 312, and 306, $7.98 each.

2533 313: No. 23. Du wahrm Gott und Davids Sohn' No 87, Risher habt ihr iichts gebeten in meinan Namen

2533 312: No. 92, Ich hab' it Gottes Herz und Sinn ; No 126, Frhalt' uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort 2533 301: No. 34, 0 ewiges Feuer' No. 58, Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt : No. 175. Er rufet seinen q,hefen mit Namen.

The recording of the first two discs listed above was begun in May 1973 and completed in June and October 1979 and January and February 1974 sessions. The third disc was begun in February 1974 and completed in January 1975; its contents have al ready appeared in Vol. 2 of Archiv's Bach jumbo packs (2722 019, not yet released in this country; it collects nineteen cantatas on eleven discs, plus a bonus record of Kirkpatrick playing harpsichord works).

The recording dates, punctiliously noted in usual Archly style, make it clear that the cantatas were not done as integral performances but were built up number by number in a manner presumably determined by the artists' availability in Munich The unevenness of the result, however, cannot be ascribed to this, since the best of the three records (2533 312) and the dullest of them (2533 313) date from the same period. The reason must be Karl Richter's oft-noted unpredictability as a Bach interpreter. Some times he is lively and imaginative some times he plods along like the most leaden of Kapellmeisters.

Nos 92 and 126 are u stunning pair of cantatas and they are performed in exciting fashion No. 92. Ich hah' in Cottes Herz und Sinn, contains a storm at sea a chorale breaking off after each phrase into accompanied recitative--which Dietrich Fischer.

Dieskau sings in arresting, even hair-raising fashion. The storm continues in the subsequent tenor aria ("See, see, how every thing is tern off, breaks, falls"), which is done with a fine energy by Peter Schreier. The next bass aria tells of the "raging of the bu star., ,vi. is.'' in the kind of blnstery mariral imagery that Fischer-Dieskau..! always seams t!: relish--though I'm not sere how mesh I enjoy his bouncing along the l:111. returns iii sr. the. ehor,le Ilk 1:.;,..VtiVe :^"c of Le._ She,,,herd t the pastor.-.! piping of an oboo Nc 92 is an exteo,led .:anteta, to the second side. AL th^.'- t -hestra is only two oboes […]

No. 126, Erhalt' uns, Herr, bei deinem Wort, is short but grand. "Luther on the warpath again" is Alec Robertson's phrase for it; a trumpet joins a pair of oboes. But the most lively aria, the bass's "Sturze zu Boden," has continuo only. The singer leaps or runs between the E below the bass staff and the E above it; Theo Adam sings it all in fine style and with fine voice. Richter adds a bassoon to the continuo bass line, which goes tumbling down into the abyss and then swiftly clambers up again, step by step, until the bass's fierce defiance seems to send it plummeting once more. There is also a very taxing tenor aria containing bar after bar of rapid, elaborately spun coloratura, alternating roulades and repeated notes. Richter takes it at a spanking pace, and Schreier brings it off by the skin of his teeth.

The three works on 2533 306 are Whitsun cantatas. No. 34, O ewiges Feuer, is a re write of a wedding cantata (No. 34a), an attractive piece with a particularly attractive alto aria, warmly and smoothly sung by Anna Reynolds. No. 68, Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt, contains the celebrated and oft-recorded "My heart ever faithful." To discover it in its original setting is a joy:

There is a lively cello obbligato, and at the end, when the voice has done, violin and oboe break in to make a trio-sonata coda.

Edith Mathis is not quite ideal, for her voice seems to have darkened; she does not efface memories of Isobel Baillie. But to hear the original accompaniment (Miss Bailine had full orchestra; Margherita Perras had organ; I forget what Schumann-Heink had) is a delight. In No. 175. Er rufet seinen Schu fen, the pastoral imagery of the text is reflected by three recorders, here not always precisely in tune. There is a very florid bass aria, which Fischer-Dieskau sings in his bouncing-along-the-notes manner.

Nos. 23 and 87 are the disappointments.

Du wahrer Gott is a magnificent work that Bach composed, it seems, to demonstrate resourcefulness and mastery, when applying for the Leipzig job. But Richter trudges through it; his textures are thick and heavy.

And so they are in Bisher haht ihr nichts gebeten, where his slow tempo makes the alto aria seem interminable, and the lilting 12/8 of the tenor aria (in a major key. after three arias in the minor) has no spring.

In Nos. 23 and 34, comparisons arise with the Telefunken Das olte Werk versions sung by boys and men and played on instruments that Bach would have recognized. Richter's performances represent something between the old Bach style of Mengelberg and Albert Coates and the "authentic" Bach style of Harnoncourt and Leonhardt. And while they are closer to the latter-orchestra and chorus are slimmed: the inflections are not nineteenth-century Romantic; the players have made moves in a baroque direction-they still must seem like a step backward to anyone familiar with the Telefunken series. That series has some way to go before it reaches Nos. 92 and 126; and therefore anyone impatient to possess those cantatas can safely he recoil) mended to Richter's vivid performances.

The album essays by Reinhard Gerlach are interesting: three short studies, complementary but not overlapping, of the cantata as a literary form, in relation to Bach's handling of it. Especially interesting are a few detailed notes on the changes, in the cause of directness, that the composer introduced into the texts by Mariane von Ziegler, the poetess of Nos. 68, 87, and 175.

-A.P.

============

Critic's Choice

The best classical records reviewed in recent months.

BACH: Flute Works. Robison, Cooper. VANGUARD VSD 71215/6 (2), March.

BACH: Italian Concerto; French Overture. Kipnis. ANGEL S 36096, Jan.

BARTOK: Bluebeard's Castle. Troyanos, Nimsgern, Boulez. COLUMBIA M 34217, Feb.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 6. Ferencsik. HUNGAROTON SLPX 11790, March.

CHERUBINI: String Quartets. Melos Ot. ARCHIV 2710 018 (3), Jan.

GOTTSCHALK: Piano Works. List, Lewis, Werner. VANGUARDVSD 71218, March.

HANDEL: Organ Concertos. Rogg. CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CSO2 2115, 2116 (4), Jan.

HAYDN: Symphonies Nos. 99, 100. Bernstein COLUMBIA M 34126, Feb.

Liszt: Concerto No. 1 et al. Ginerrez, Previn. ANGEL S 37177. Kiss, Ferencsik. HUNGARATON SLPX 11792. Berman, Giulini. DG 2530 770. Feb.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 3. Home, Levine. RCA RED SEAL ARL 2-1757 (2), March.

MESSIAEN: Quatuor pour la fin du temps. Tashi. RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1567, Jan.

MEYERBEER: Le Prophete. Scotto, Home, McCracken, Lewis. COLUMBIA M4 34340 (4), March.

Mozart: The Impresario. Cotrubas, Welting, Davis. PHILIPS 9500 011, Feb.

NIELSEN: Orchestral Works. Blomstedt. SERAPHIM SIC 6097, 6098 (6), Feb.

Rossini: Elisabetta. Caballe, Carreras, Masini. PHILIPS 6703 067 (3), Feb.

SCHUMANN, SCRIABIN: Sonatas. Horowitz. RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1766, Jan.

SHOSTAKOVICH: Quartets Nos 8, 15. Fitzwilliam Qt. OISEAU-LYRE DSLO 11. Cello Concerto No. 2. Rostropovich, Ozawa. DG 2530 653. Feb.

Tchaikovsky: The Nutcracker. Dorati. PHILIPS 6747 257 (2), Jan. Swan Lake. Previn. ANGEL SCLX 3834 (3), March.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Symphony No. 5. Karajan. DG 2530 699, Jan.

WAGNER: Die Meistersinger. Fischer-Dieskau, Ligendza, Domingo. Jochum. DG 2713 011 (5) Bailey, Bode, Kollo, Solti LONDON OSA 1512 5). Feb.

WALDTEUFEL: Orchestral Works. Boskovsky. ANGEL S 37208, Feb.

LEON BATES: American Piano Works. ORION ORS 76237, March.

Jost Crummy Operatic Recital. PHILIPS 9500 203, March.

DAVID MUNROW: Art of Courtly Love. SERAPHIM SIC 6092 (3). Instruments of the Middle Ages and Renaissance. ANGEL SBZ 3810 (2). Feb.

CLAUDIA MUM): Edison Diamond Discs, Vol. 2. ODYSSEY Y 33793, March.

FREDERiCA VON STADE: French Opera Arias. COLUMBIA M 34206, Feb.

==============

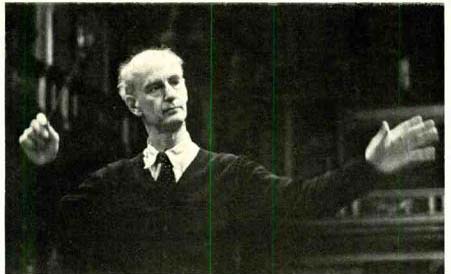

Berlioz: Requiem, Op. 5. Stuart Burrows, tenor; Choeurs de Radio France. Orchestre National de France, Orchestre Philharmonique de Radio France, Leonard Bernstein, cond. [John McClure, prod.] COLUMBIA M2 34202, $13.98 (two SQ-encoded discs, automatic sequence). Tape: NE, MT 34202, $15.98

BERLIOZ: Requiem, Op. 5. Robert Tear, tenor; City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Louis Fremaux, cond.

[David MoRley, prod.] ANGEL SB 3814, $13.98 (two SQ-encoded discs. automatic sequence).

Comparison:

Davis / London Sym. Phi. 6700 019 The Berlioz Requiem is among the classic challenges for the recording engineers-so much so that the musical challenge it presents may easily be relegated to second place. In the long run, though, it's the performance that counts. I can still listen with pleasure and excitement to the wartime French recording conducted by Jean Fournet, for example, since it strongly conveys the thrust of the work, if hardly all of its breadth and depth. Of course the Requiem is, among other things, about sounds in space, about the contrast between immense sounds and small ones-but unless these sounds are shaped with purpose and intensity the most splendid reproduction will de liver to us only a hollow shell.

Another important postulate: For all that its instrumental extravagance-the brass bands and kettledrums, the trombone-and-flute chords-has garnered most of the headlines over the years, the Requiem is a choral work. The tenor soloist appears only briefly, in a single movement; no matter how good, he can hardly carry the work or at least make it tolerable (as, for example, superior soloists in the Verdi Requiem can to a significant degree counterbalance inadequate choral work). And even when the orchestra is crucially involved, as in the main section of the "Lacrymosa," the primary line is conveyed, un-doubled by instruments, in the chorus; weakness here can vitiate the entire effect.

That is what happens, I am afraid, in the Fremaux performance. so that this rather central tableau in Berlioz' epic polyptych fails. Elsewhere, the citizens of Birmingham don't do badly. Their sound is, in fact, more homogeneous than that of Bernstein's stronger-voiced Parisians, and somewhat more smoothly registered (although this advantage is rather offset by disc distortion in the loudest passages). The crunch comes when these new recordings are confronted with the work of the London Symphony Chorus in Colin Davis' Philips recording, which is clearly the result of much more de tailed rehearsing and shaping. The individual lines are more finely distinguished, the phrases in each line carve up and down with more sense of destination and climax.

None of these performances is entirely free of ensemble inexactitude-keeping together the cellos, contrabasses, low winds, and choral basses is a frequent problem.

probably compounded by their geographical dispersion in the recording halls-but the music that comes off the Philips recording is by far the most vividly imagined and executed; only there, for example, do the counterpointing rhythms of the "Lacrymosa" speak out with full authority. Only there does the Dies free emerge as a complex series of phrases, not just a long sausage of a melody.

Not that the two new recordings are really very much alike. As intimated. Bern stein has the stronger forces to work with, and he rouses them to considerable excitement in the big moments. Elsewhere, there are some relatively inert passages; the emergence of a pulse under the first choral entry ("Requiem aeternam") is obscure, and the movement never really gets under way. Complementarily, Fremaux is rather good here, with a nice swing that often serves him in good stead. Bernstein has his demonstrative moments, too-big distentions of tempo at the climaxes in the Offertorium, for example, that far exceed (and precede) Berlioz' indications of "un poco ritenuto"; as much expansion as the composer wanted is already composed into the piece here, with the thinning-out of rhythmic density.

The Bernstein performance was recorded in the chapel of Les Invalides in Paris, the site of the work's first performance (Scherchen's Vega/Westminster recording of two decades ago, now on Turnabout THS 65017/8, was also recorded there-rather dimly and distantly). Angel doesn't report the locale of its recording, but the space is evidently of comparable dimensions if somewhat less overbearing resonance. In Les Invalides, at one point in the "Rex tremendae" the echoes of "Confutatis male dictis" pretty well submerge the chorus' suddenly soft "Jesu," and when all six choral parts get going in the "Quaerens me" a certain congestion results. Angel's sound has less immediate impact, while the Phil ips engineers (working in London's West minster Cathedral) managed the happiest compromise of all: keeping the initial sound forward and clear, the resonance sufficiently distant that it doesn't obscure what's going on (check out the string figurations in the Offertorium, for example).

As for that tenor soloist: The first time around the Sanctus, Stuart Burrows walks off with most of the honors, using sweet head tones to pretty ravishing effect, but on the repetition he seems strained and has to lunge for one B flat. Angel's Robert Tear is throughout too loud and in serious technical difficulties (a point to the EMI engineers here, for the bass-drum strokes are more "felt" than heard-much the best realization of the effect Berlioz wants). On Davis' recording, Ronald Dowd is certainly too loud, but his tone is consistently firm and the lines are very cleanly shaped.

All three of these recordings give us the shorter version of the "Quaerens me," as published in the orchestral score-some thing that the editor of Columbia's liner notes evidently does not know, for the excised words ("culpa rubet vultus meus") are printed in the text on the liner. But then Columbia's annotator seems to be unaware of the repeat of the "Hosanna," let alone the fact that the entire final movement is re-capitulatory. At that, his work is preferable to the gossipy history and patronizing musical observations that Angel offers. Here again, Philips gains the palm, with a literate and knowledgeable essay by David Cairns.

-D.H.

Technical and quad note: Columbia in forms us that the Bernstein recording is to be replaced by a remastered, two-channel-only version, which will be indicated by a "2" series stamper number. As no date is given for its appearance, this review is based on the version that has been in circulation for several months.

If your cartridge can track the loudest passages of the recording (and some top-of-the-line models can't), it has unusually good dynamic range. It could, in fact, be recommended as a very rigorous cartridge test.

Both recordings of the Berlioz Requiem offer full and well-balanced quadriphonic sound, with most of the performing forces at the front and large amounts of hall ambience (particularly the Columbia recording) at the sides and rear. When the "Tuba Mirum" comes along with all the fancy stuff, both disci are reasonably equal to the task. The edge on positional accuracy is with the Angel, which not only pinpoints the auxiliary brass choirs well, but also seems to preserve more of the details of the music. The Columbia trades away some of the finer points in favor of a powerful, sweeping opulent sound that fairly over whelms the listener at times.

It would be hard to say whether it is the intrinsic qualities of the music that make it so, or whether it is a matter of recording technique, but these discs represent a severe test for a matrix decoder. One full-logic unit that we tried produced anomalies such as a thunderous roll of the timpani (in the "Tuba Mirum" on Columbia) that parted like the Red Sea to allow free pas sage of the choral basses. A replay using a less ambitious but more accurate decoder gave a more credible sonic image.

-H.A.R.

BRAHMS: Quintet for Clarinet and Strings, in B minor, Op. 115. Richard Stoltzman, clarinet; Cleveland Quartet. [Jay David Saks, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1993, $7.98.

Tape: MO ARK 1-1993, $7.95, a ARS 1 1993, $7.95.

Richard Stoltzman is a clarinetist with real personality, a limpid sound. and a memorably wide dynamic range. But in the first movement of the Brahms clarinet quintet both he and the Cleveland Quartet members tend toward a self-indulgence at odds with the music. Thus the already too dreamy tempo (hardly an allegro) is perversely slackened at bar 51 for the sake of a largely irrelevant, kittenish clarinet portamento. And while the recording balance admirably makes the clarinet a team member rather than a soloist, Brahms's crucial part writing is compromised by the players' failure to form a genuine ensemble. As a result, the movement's stark energy and rhythmic urgency are sapped.

The remaining movements, however, are quite wonderful. In the Adagio the gently autumnal treatment pays dividends, and the last two movements are given with more verve and altogether crisper incisiveness. I felt a bit uncomfortable with the cellist's mannered rubato in the final variation; such harmonic pointing can be achieved through phrasing and dynamic subtlety rather than conspicuous distortion of the basic rhythmic ostinato.

Whatever my reservations, this is a serious, if controversial, presentation of one of Brahms's most sublime works. By comparison, I now find the admirably robust and straightforward Ettlinger/Tel Aviv version (Oiseau-Lyre SOL 146, September 1973) somewhat extroverted and lacking in nuance.

--H.G.

-----------Arthur Grumiaux Distinguished Brahms performances

BRAHMS: Sonatas for Violin and Piano: No. 1, in G, Op. 78*; No. 2, in A, Op. 100% No. 3, in D minor, Op. 108'. Trio for Violin, Horn, and Piano, in E flat, Op. 40.* Arthur Grumiaux, violin; Francis Orval, horn (in Op. 40);

Gyorgy Sebok, piano. PHILIPS 9500 161* and 9500 108', $7.98 each.

Comparisons-sonatas:

Szeryng, Rubinstein RCA LSC 2619, 2620 Zukerman, Barenboim in DG 2709 058 These are distinguished performances, gorgeously reproduced, but they may not be to all tastes. The emphasis is on refinement and delicacy. Grumiaux at his best is a remarkable instrumentalist, a violinist with impeccable intonation, perfect bow control, and aristocratic musical impulses.

Thus from the very beginning of the G major Sonata his firmly centered, luscious tone and superior sense of flowing line create a lofty mood, fully seconded by Gyorgy Sebok's knowing, sensitive chamber-style playing.

That is the merit-and, to some extent.

the limitation-of these interpretations. The more passionate, solistic elements of the stormy D minor Sonata, for example. are played down and consequently less dramatic than in the Szeryng/Rubinstein and Zukerman/Barenhoim performances.

While the C major and, to an even greater degree, A major Sonatas are admirably served by the Grumiaux/Sebok approach, the D minor Sonata and the horn trio, for all their interpretive elegance and distinction, strike me as slightly lacking in drama and brio. Francis Orval, a horn player previously unknown to me, contributes a liquid legato and chaste phrasing. with just a trace of saxophone-like vibrato. The balance in the trio, incidentally. is exemplary: All three instrumentalists are in just ratio with out any loss of impact or inner-voice clarity.

The more I hear the Zukerman/Barenboim DC, set. the more I like it (the violin sonatas, at least: the coupled viola sonatas are a different story). The touch of gypsy vibrato in Zukerman's tone raises the music's emotional temperature, and Barenhoim is more willing than Sebok to assert himself solistically. As a result, Zukerman and Barenboim tend to complement Grumiaux and Sebok, succeeding best in the D minor Sonata. Neither Sebok nor Barenhoim.

however, can challenge the keyboard work of Rubinstein, who manages to create remarkably sophisticated ensemble effects without in any way lessening his normal individualistic ardor. Since Szeryng can rival Grumiaux for every-note-in-place aristocratic musicianship and seems, on this occasion, to have been sparked by Rubinstein's greatness, the RCA performances hold a slight edge over the Philips and DC.

Add to these the excellent individual ac counts of these pieces by Oistrakh, Szigeti, Milanova, and others. and you realize that few works have been as lucky on disc.

-H.G.

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 2, in D, Op. 73.

Danish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Jascha Horenstein, cond.

UNICORN UNS 236, $6.98 [recorded in concert, March 16, 1972] (distributed by HNH Distributors, Box 222, Evanston, Ill. 60204).

This performance, from an actual studio concert, does not represent Horenstein at his best. In the first place, instrumental balances are faulty: Inner voices (especially second violins and violas) are exceedingly reticent compared with upper and lower lines. Then, either the engineers have compressed the dynamic range or really good soft playing is absent. Phrasing tends to break down into bar-by-bar fragments, most notably in the slow movement, where the problem is compounded by the very broad tempo (which itself runs down toward the end). Orchestral discipline is not up to what I would expect from either Horenstein or the Danish Radio Symphony: note the ragged brass chording at bar 348 of the first movement and the late woodwind attack at bar 62 of the Adagio.

The approach itself is a weighty one.

From the first movement (with repeat) on, all goes rather deliberately, yet without the sweeping ardor and lushness of sound that I find most suitable for a "big" Second. It's an approach with a respectable following including Szell and Haitink, to judge from their recordings-but among current SCHWANN listings I'll stick with Boult (Angel S 37032), Monteux (Stereo Treasury STS 15192), Steinberg (Westminster Gold WGS 8153), and Karajan (DG 138 925).

-A.G.

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 4, in E mi nor, Op. 98. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Fritz Reiner, cond. [Charles Gerhardt, prod.]

RCA GOLD SEAL AGL 1-1961, $4.98.

This performance, previously available only in the Reader's Digest recordings series, is typical of Reiner in many ways, including the immaculate polish. Indeed, the Chicago Symphony in his Brahms Third, recently reissued in the Gold Seal series as AGI.1-1280, has nothing on the Royal Phil harmonic in unflustered accuracy and gleaming brightness of sonority.

Phrases are always turned with dapper understatement, and there is a certain impersonality. This Brahms Fourth doesn't fit any of the neat pigeonholes: luxuriantly Romantic, firmly Teutonic, rigorously incisive. Reiner often had the knack of making fast tempos Weill leisurely and slow ones taut, or at least light, sometimes one isn't even sure which sleight of hand is being performed. I think the finale is one of the steadier ones around, and the scherzo has plenty of martial energy.

I'll go out on a limb: You can't get a better Brahms Fourth at the price.

-A.C.

BRITTEN: A Charm of Lullabies, Op. 41; Folksong Arrangements. Bernadette Greevy, mezzo-soprano. Paul Hamburger, piano. LONDON STEREO TREASURYSTS 15166, $3.98.

Folksong Arrangements: O can ye sew cushions?: There's none to soothe; O wsly. waly; The Ash Grove; Sally Gardens; The trees they grow so high; Come you not from Newcastle?: Sweet Polly Oliver: Bonny Earl o' Moray; Oliver Cromwell

A Charm of Lullabies was composed in 1947 to five texts by various poets The moods and character of the Lullabies are 3'2 contr2sted as one end imagine; Britten's settings fit the words vucci ct1y; and the piano is a creative pa-tae" But for me the ultimate art-song purtruyal of childhood's wide-eyed wonderment remains Mussorgsky's Nursery cycle--Britten always strikes me as the cleverly stylized producer of chic repertoire, even when he is trying to speak directly to the heart.

The accompaniments to the ten Britten arranged English folksongs )N9 -1"i hero provide ample opportunities fir r `!,e composer's fancy. "The Ash Cr, . ' ample, features evocative use I '''.v: ity.

Bernadette Greevy gives perfurma.. of Peter Pearsian vividness, and the 1970 (not previously issued here) is discreet-though my copy had somewhat noisy surfaces Full text c,4e,-nvided. A.C.

Buxteriude: Cent.4..t Wachet auf, ruff uns die Stiinn. Jesu meine Freude; Herzlich lieb hob i^h Dich, o Herr. Herrad Wehrung and Gundula Berndt -Klein, sopranos; Frauke Haasemann, mezzo; Friedreich Melzer, countertenor; Johannes Hoefflin, tenor; Wilhelm Pommerien, bass; Westphalian Choral Ensemble, Southwest German Chamber Orchestra, Wilhelm Ehmann, cond. NONESUCH H 71332, $3.96.

The works on this disc are called "cantatas, ' a designation as vague as "concerto"-the two being interchangeable when applied to this genre in the seventeenth century. (Bach still called most of his cantatas concertos.) We might say that the entire century was under the auspices of the concerto principle, whether the mu sic was instrumental or vocal. The aim was to loosen the uniform texture of a composition by creating contrasts: chorus vs. chorus, chorus vs. solo, solo vs. instruments, and cc forth.

The cantatas recorded here are "spiritual concertos"; they are not church music like most of Bach's cantatas, but early examples of public concert music of an elevated sort.

Such cantatas were performed in Ltibeck cathedral at-evening musicals" (Abend musiken) for the enjoyment and edification of the well-to-do business patrons of the Hanseatic city. They ere fine works, rich in ideas colors, and moods.

The performances, while decent enough, bring, out these qualities only in spots, Conductor Wilhelm Ehmann doctored the first cantata, Wachet auf, a bit, adding trumpets and a trombone. While this is not a musicological crime, as Buxtehude was no stranger to large ensembles and such additions were often made in his time, these works are predominantly lyrical and intimate and do not need reinforcement. More over, faulty microphone placing makes the brass too prominent. Much of the playing is too uniform, even plodding. The singers, except for the sturdy bass Wilhelm Pommerien. are timid, and the prevailing color is somewhat gray. Sopranos Herrad Wehrung and Gundula Berndt -Klein do well in the quiet strophes, and countertenor Friedreich Melzer is not at all bad, but the Italianate roulades are not taken with enough freedom by the German singers, and Ehmann's rhythm is soft and lacking in variety. The chorus is good, if a little distant: the organ continuo is good.

-P.H.L.

CHOPIN: Polonaises. Maurizio Pollini, piano.

[Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 659, $7.98.

Tape: (F.0 3300 659, $7.98, Polonaises: No. 1, in C sharp minor. Op. 26, No. 1; No. 2, in E flat minor. Op. 26. No. 2; No. 3, in A, Op. 40. No. 1; No. 4, in C minor, Op. 40. No. 2; No. 5. in F sharp minor, Op. 44; No. 6, in A flat, Op. 53; No. 7. in A flat, Op. 61 (Polonaise-fantaisie).

The piano sound on this otherwise splendid disc is a trifle bleak and clangorous--a result, one suspects, of both engineering and playing. (Pollini's pianism. for all its coloristic sensitivity, veers more toward the linear than toward the massive or ripely sensual.) But the ear is quickly reconciled, and only in the Polonaise-Fantaisie was my enjoyment diminished by the actual tone quality. Pollini's account has purity of feeling, a distinguished sense for rubato effects, and a welcome structural grasp. yet I found it too inhibited emotionally, lacking in color and magical atmosphere.

In a more overtly linear piece like the C sharp minor Polonaise, however. Pollini's rare sensibility is just what is needed. His rhythm is full of both snap and lilting, subtly nuanced flexibility. In the companion E flat minor Polonaise, he avoids thick textures and gives the music brooding poignance: I have heard more explosive readings but few that rival this one for eloquence and detail. The popular A major is taut, symmetrical, and rather Mozartean in feeling. (Mozart was, after all, a spiritual forebear of Chopin, even if one is surprised to he reminded of it in this particular piece!) Pollini's exquisite voicing again pays dividends in the opening section of the C minor, which can so easily sound square and podgy (compare Frankl and Ohlsson). The new account of the big F sharp minor is surprisingly similar to the one the eighteen-year-old Pollini made directly after winning first prize in the 1960 Warsaw Chopin competition, a tribute to his early maturity.

There has been a heightening of perception, most conspicuously in the complex central section. I have heard only Horowitz (and not on record) give an unarguably greater account.

The biggest surprise is Pollini's Op. 53, which recalls Arthur Rubinstein's proprietary way with the score: Their performances have the same sense of expansion and rhetorical inflection. Perhaps this will put to rest once and for all the notion that Pollini is a dry, metronomic literalist.

-H.G.

Couperin: Concerts royaux (4); Noveaux concerts (10). Heinz Holliger, oboe; Aurele Nicolet, flute; Thomas Brandis, violin; Josef Ulsamer and Laurenzius Strehl, viole da gamba; Manfred Sax, bassoon; Christiane Jaccottet, harpsichord. [Andreas Holschnei der and Gerd Ploebsch, prod.] ARCHIV 2712 003, $31.92 (four discs, manual sequence).

For sheer elegance the music on this handsomely produced set would be hard to heat.

Couperin may plumb greater depths of rhetorical pathos in the Legions de tenebres and reveal a still more individual vein of fantasy in his later harpsichord pieces, but these instrumental consorts (for that, not concertos, is the correct English translation here) show him as the supreme master of the social music of his time and place. A highly civilized time and place, it goes with out saying. Versailles and Paris in the decade between 1714 and 1724.

The four Concerts royaux, the composer tells us, were originally written for the aged Louis X IV's Sunday chamber concerts at Versailles in 1714 and 1715, the last years of his life, though Couperin did not publish them until 1722, as an appendix to his third book of harpsichord pieces. The remaining ten consorts, more diverse in style and character, came out two years later and re flect a wider spectrum of taste. Among them we find not only the more or less standard sequence of idealized dance movements, but also a full-scale suite, "Dans le goat thecitral," consisting of airs each with its own clearly marked choreographic character, and another, called Ri tratto dell'amore, in which the individual titles ("Le Je-ne-sqay-quoy." "La Noble (ierte") evoke the whimsical world of the harpsichord suites.

The Italian name for this consort reminds us, incidentally, that the whole set of ten bears the subtitle Les Cotits-reunis, refer ring to the supposed union in these pieces of the current French and Italian styles of instrumental music. Couperin was too complete a professional not to have achieved what he set out consciously to do, hut for us it is certainly the French style that predominates, with its finely chiseled but always lyrical melodies and its subtle refinements of harmony and rhythm. And these are the qualities that this group of players (who are augmented in the "theatrical" consort by an additional flute. oboe, and violin) seems consistently to relish. Following Couperin's own hint, when he tells us in his preface to the Concerts royaux that they were originally played by a violinist, two oboist/bassoonists, and a viol player, with Couperin himself at the harpsichord, the present recording shares the music sensibly between these instruments, throwing in a flute for good and entirely appropriate measure.

Purists may be offended that Heinz Holliger and Ann Nicolet are not (at least so far as I can tell) playing on eighteenth-century instruments. No doubt this is the reason why Archly has forsaken its usual practice of including full details of the instruments in the accompanying notes, even though we are told precisely when and where the recording was made. But al though my sympathies are usually with the purists (who wants to be an impurist, after all?), I have to admit that the refinement of Holliger's and Nicolet's playing soon converted me. Not quite at once in Holliger's case: his line is so tautly drawn, his ornaments so replete with nervous tension, that at first I was tempted to dismiss his playing as anachronistic. But the tension is con trolled with such exquisite taste that one finishes by being seduced. Thomas Brandis' violin, which certainly sounds like an authentic eighteenth-century instrument, is no less eloquent in its silvery way, and the bass viols of Josef Ulsamer and Laurenzius Strehl gambol and descant in the most urbane manner in the two consorts for-instrumens a l'unisson" that they share.

The recorded sound is beautifully balanced, and the pressings beyond reproach.

One tiny cavil, though, on behalf of disc jockeys and catalogers: Why adopt sepa rate numerations for the two sets of con sorts on the record labels, and a continuous one in the album notes, so that the same work appears variously as No. 10 and No. 14?

-J.N.

CRUMB: Makrokosmos II. Robert Miller, piano. [Thomas Frost, prod.]

ODYSSEY Y 34135, $3.98.

This is the second of three works entitled Makrokosmos written between 1972 and 1974. (The first and third have already been recorded by Nonesuch, on 1-1 71293, June 1974. and H 71311. October 1975, respectively.) Like Vol. 1. Vol. 2 is scored for solo piano, amplified by means of a conventional microphone, and consists of twelve pieces divided into three groups of four each, with each piece bearing a descriptive title as well as the name of one of the twelve signs of the Zodiac. (Vol. 3, Music for Summer Evening, scored for two amplified pianos and two percussionists, has a different formal layout.) This score contains many of the features that have come to be identified with Crumb's style: The piano sound is altered through the use of such external props as paper, glass tumblers, and a wire brush: strings are played pizzicato: harmonics are employed; the pianist sings, chants, and whistles as well as plays his instrument.

Yet for all these sonic innovations, the piano writing is closely bound to the nineteenth-century virtuoso tradition; the kinds of figurations and textures used, even such special effects as the sudden opposition of registral extremes, have their close parallels in Schumann and Liszt. The spell of such later composers as Debussy and Bartok can also frequently be detected, not least of all in the title and formal organization of the piece. These associations are nu doubt intended by the composer, and provide the work with a "historical resonance" that supplies an interesting accompaniment to those acoustical resonances Crumb uses to such telling effect: sounds that gradually die out while being sustained by pedal, etc.

Despite its division into twelve sections, Mokrolsosinus II creates a distinctly unified impression. As pianist Robert Miller re marks in his excellent liner notes, there is a sort of intensification to the eighth piece and then a gradual relaxation thereafter until the composition reaches its peaceful close. Yet each piece also projects a distinct character of its own: and each evokes clearly the associations suggested by its title, whether through literal sound imitation, as in No. 9 (-The Cosmic Wind"). or through a more general evocation of its character, as with the ominous minor chords in No. 8 ("A Prophecy of Nostradamus").

The performance by Miller is very fine, though his whistling is somewhat shaky in No. 10 ("Voices from 'Corona Borealis' ") a real tour de force for the whistler, who must not only play as he whistles, but also, in one section, apply "Monteverdi trills" (produced by "a rapid series of staccato ejections of breath"). The recorded sound is excellent: and in addition to Miller's helpful notes, the names of the movements are listed as well as the composer's suggested markings for the character of the individual pieces (e.g., "Exuberantly, with primitive energy" for No. 1).

-R.P.M.

Dvorak: Symphony No. 7 in D minor, Op. 70. Concertgebouw Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond.

PHILIPS 9500 132, $7.98. Tape: 7300 535. $7.95.

Comparisons:

Szell / Cleveland Orch. in Col. D3S 814 Rowicki/London Sym. Phi. 6500 287 Kubelik / Berlin Phil. DG 2530 127 Monteux/London Sym. St. Tr. STS 15157 Neumann /Czech Phil. Van. SU 7 The most somber, and perhaps greatest, of Dvorak's symphonies has always fared well on disc (to the admirable recordings listed above I could add half a dozen or more not currently available domestically), and this newest version, the beginning of a Davis/Concertgebouw Dvorak cycle, continues the tradition.

Davis' interpretation generally belongs to the taut school exemplified by Szell and Rowicki. Tempos throughout, while never rushed, veer toward militancy, with great heed paid to rhythmic energy and regularity of phrasing. In the third movement, Davis clarifies the subordinate theme more explicitly than anyone I have heard, and in the finale's second theme he will have none of the rhapsodic heaving and hauling often encountered (which admittedly can be done to good advantage, as Kubelik shows in his Berlin recording).

Yet unlike Szell-and, to a lesser degree, Rowicki-Davis manages to secure this knife-edged precision and refinement of tone and balance without sacrificing the heft of Dvorak's scoring, thanks no doubt to the superbly vigorous, dark-toned playing of the Concertgebouw. Similarly, he captures something of Monteux's robust energy without the momentary ensemble lapses and textural crudities. Some may still prefer the more lyrical approach of Neumann or the more rhapsodic one of Kubelik/Berlin, but I am tempted to award Davis and the Concertgebouw pride of place.

Philips' moderately distant, yet exquisitely defined recording captures the bite and dynamic range to perfection.

-H.G.

ELGAR Enigma Variations-See Schoen berg: Variations for Orchestra.

FOSTER: Songs, Vol. 2. Jan DeGaetani, mezzo-soprano; Leslie Guinn, baritone; Camerata Chorus of Washington; Gilbert Kalish, piano and melodeon; Douglas Koeppe, flute and piccolo; Howard Bass, guitar; James Weaver, piano. (Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] NONESUCH H 71333, $3.96.

The Voice of Bygone Days: Better Times Are Corning; Linger in Blissful Repose: There Are Plenty of Fish in the Sea: My Old Kentucky Home: Soiree Polka: Larry's Good Bye. Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming: We Are Coming. Father Abraham. 300.000 More: Come with Thy Sweet Voice Again; Katy Bell; Hard Times. Come Again No MC:3; Village Bells Polka; The How for Thee and Me; Sur -^! -Longings.

When Jan iiel,aeiani and Leslie Guinn brought out the first volume of songs by Stephen Foster (Nonesuch H 71268). I was absolutely ecstatic about their work. This was the way Foster should be sung; the record was living proof that he was a really great composer. All you had to do was to sing what he had written, and the man's genius shone through.

The sequel is a profound disappointment: for the producers have gone fancy: The fifteen Foster selections are arranged in no less than thirteen different ways. We have the singers not only with piano accompaniment, but with melodeon, with guitar, with flute, with piccolo, with chorus, and with every permutation and combination thereof. Only three songs are sung by DeGaetani straight (that is. with simple piano accompaniment); Guinn sings only one.

It may be quite true that way back then a Foster song would be accompanied by a guitar or melodeon if a piano wasn't avail able, and if a flutist happened to be visiting he might have thrown in his two cents. But to find this kind of olla podrida all at the same time would have been a virtual impossibility.

Furthermore, I must say that Guinn shows a decided tendency to veer away from the printed notes-in "My Old Kentucky Home," for instance, he varies both rhythm and melody. And by and large, the materials in Vol. 2 are not nearly so well chosen as those in Vol. 1 (which, however, only scratched the surface). Nevertheless, DeGaetani can do no wrong, and the best things about the disc are the songs she sings so sympathetically and simply.

I was also disappointed in the work of the Camerata Chorus of Washington, which is featured in "Come Where My Love Lies Dreaming." In his choral writing, Foster arranges his voices STAB, and the main melody is invariably given to the tenor.

This is particularly noticeable in this song, where the lower voices flow on serenely while the soprano unexpectedly enters with a sort of simple descant. For some reason, the Camerata's sopranos invariably manage to sound screechy when they should sound velvety.

Full texts of the songs as sung are provided, but not all the verses in the originals are sung. The instruments, mostly from the collections of the Smithsonian Institution.

and contemporaneous with Foster and are fully described. The note by Jon Newsom of the Library of Congress strikes me as more literary than informative. One further small point: There does not seem to be any way to discover whether the piano accompaniments are being played by Gilbert Kalish or James Weaver. Or doesn't it matter?

-I.L.

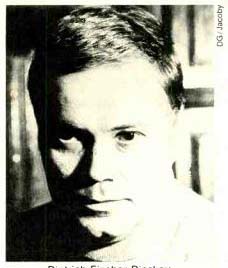

------- Wilhelm Furtwangler-conducting and composing with variable

results

FRANCAIX: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra; Suite for Violin and Orchestra; Rhapsody for Viola and Small Orchestra. Claude Paillard-Francaix, piano; Susanne Lautenbacher, violin; Ulrich Koch, viola; Luxemburg Radio Orchestra, Jean Fraricaix. cond. TURNABOUT TV-S 34552, $3.98.

FRANCAIX: Divertirnento for Flute and I u1ia.nber Orchestra'; Suite for Solo Flute, Quintet for Winds*. Ransom Wilson, flute, urplieus Chamber Ensemble*; Musical Heritage Wind Quintet'. MUSICAL HERITAGE MHS 3236, $3.50 (Musical Heritage Society, Musical Heritage Building, Oakhurst, N.J. 07755).

Unlike Poulenc, whom he superficially resembles here and there, Francaix does not usually use contrasting material to provide relief from his sometimes jaunty, sea -.c times warmly flowing, but always super-suave musical ideas, which instead often are repeated to the point of puerility. His music may be "completely, unabashedly, and irrevocably French," as Ransom Wilson points out in his liner notes for the Musical Heritage disc; but it is so only in accordance with a cliche, belied by countless Gallic endeavors, that would have all French artists concerned primarily with stylistic hedonism.

The concertante idiom is the one in which Framiaix is perhaps the most successful. for the tensions created between soloist and orchestra help compensate for the sameness that tends to water down his style. In the four concertante works on these two recordings-the piano concerto (1936), the suite for violin and orchestra (1934), the rhapsody for viola and small orchestra (1946), and the divertimento for flute and orchestra (arranged in 1974 from an earlier flute/piano piece)-the composer uses the almost constantly moving solo parts as a latticework around which myriad melodic and instrumental patterns weave their attractive ways. None of it is very "deep," even in the sense that Satie and Poulenc are deep. And those enamored of concertante pyrotechnics won't find much to gasp at here, although the reworked flute part in the divertimento has more virtuoso eclat than the solo writing in the other three works. But if Framiaix relentlessly concentrates on flat surfaces, in these pieces he has at least made the surfaces extremely attractive through some judicious tautening.

I must say, too, that the short solo-flute suite (1962) manages to sustain the listener's attention and that the 1948 wind quintet, which has a particularly appealing theme-and-variations third movement. de serves its popularity. I found the performance of the quintet somewhat blunted, especially in the way the mosaically composed instrumental lines lack definition. Ransom Wilson, on the other hand, is obviously an extremely accomplished and versatile flutist, with a sharp attack and an ability to radically change the character of his playing to suit an individual passage or movement. Note. for instance, his almost muted performance of the slurred, chromatic perpetuum mobile of the divertimento's third movement.

The Musical Heritage disc also benefits from extremely good sound reproduction.

Turnabout's sound and performances are unexceptional but good enough not to be bothersome.

-R.S.B.

FRANCK: Symphony in D minor.* WAGNER: Siegfried Idyll.' Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Wilhelm Furtwangler and Hans Knap pertsbuscht. cond LONDON TREASURY R 23207, $3.98 (mono) ['from LONDON LL 967, 1954, 'from LL 1250. 1955]

FRANCK: Symphony in D minor; Redemption (symphonic piece). Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim, cond. [Gunther Breest, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 707, $7.98 Tape: CFO 3300 707, $7.98.

FRANCK: Le Chasseur maudit; Nocturnes; Psyche (orchestral version). Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano', Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim, cond. [Gunther Breest, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 771, $7.98 Rehearing Furtwangler's bizarre interpretation of the Franck D minor Symphony, one wonders whether he knew what "lento" (or "allegro non troppo." or "a tempo") means. Admittedly, some of his tempos taken separately might-with some stretch of the imagination-be justifiable: put them together, however, and you have trouble.

In the first movement, which poses real problems of transition and structural unity even in the best circumstances, Furtwangler inverts and virtually destroys the nor mal dichotomy between the Lento and Allegro non troppo sections. In his overly brisk Lentos. all the spiritualism and mystery simply vanish (and that. after all, is what the piece is about). The tempo barely changes for Allegro non troppo and, in fact, gives the illusion of getting slower. Then. at the grandiose recapitulation. there is a lurch at the return of the alleged Lento.

Only at the very end, when Franck augments the note values, is there anything approaching what the tempo ought to have been from the start.

There are more problems: the disregard for both a tempo markings, the uncalled-for ritenuto along with the molto diminuendo at bar 226, the swollen portentousness of the string figurations at bars 191-95, the generally unidiomatic, monochromatic Vienna woodwind playing throughout the symphony. (In the second movement, the all-important English horn sounds particularly threadbare and starved.) The second movement is not so much eccentric in tempo as stodgy and overemphatic, but the finale returns us to the aimless meandering of the first movement.

The sound, however, is highly acceptable; this is one of the last and, from a purely technical standpoint, best of Furtwangler's Vienna recordings.

Since Daniel Barenboim is an ardent admirer of Furtwangler, one is not surprised to discover in his first movement the same fast Lento and slow Allegro, the same fondness for overripe expressive lingering. The second movement goes more crisply, and the Orchestre de Paris, while less decisive than the Vienna Philharmonic, has more of the requisite opulence. Ironically, Barenboim projects Furtwangler's tempo aberrations less decisively and authoritatively, and the resulting performance sounds more mystical, less hard to like.

The shorter Franck pieces are acceptably played, and Barenboim is not insensitive to the music's beauty. My own feeling is that this literature is best served by under playing its prominent rhetorical and mystical qualities. Toscanini's "Psyche et Eros" is a case in point: Heard alongside that plastic, yet more firmly delineated account, Barenboim's, well played as it is, sounds turgid and overripe. But make no mistake, he is improving as a conductor.

Knappertsbusch's Siegfried Idyll is a curious filler for the Franck symphony, and it happens that Furtwangler himself re corded the piece with the Vienna Philharmonic for EMI (available in Seraphim IB 6024). Knappertsbusch's genial, mellow approach works passably here, but one looks in vain for the tensile shaping of phrase and line practiced in divergent ways by Furtwangler, Toscanini, Kubelik, Walter, and Cantelli. The sound holds up well; the strings sound even rounder and warmer than in the Furtwangler Franck.

H.G.

Furtwangler: Symphony No. 2, in E minor. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Wilhelm Furtwangler, cond. [Fred Hamel, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2707 086, $15.96 (two discs, mono, manual sequence) [from LPM 18114/5, recorded December 1951].

Wilhelm Furtwangler's activity as a composer was divided into two periods. As a boy, his extraordinary musical gifts were early manifest, and he pursued composition equally with performance: works in various media, climaxing in a Te Deum that was first performed in Essen in 1911. But the demands of his conducting career-first the need to learn a broad repertory, which his early, humanistically oriented education had ignored, and then the growing demand for his services-severely circum scribed the time available for composition.

Ironically, it was the advent of the Nazis that changed this; after the 1934 showdown with Goebbels over Hindemith, when he re signed all his positions, and during similar periods of enforced inactivity later on, Furtwangler again found time to compose: two violin sonatas, a "Symphonic Concerto" for piano and orchestra, and three symphonies (the final movement of the third not completely revised when he died in 1954).

The Second Symphony was written during the last years of the Second World War, and completed in Clarens, Switzerland, on October 18, 1945. But you would hardly guess this from the music, which shows little trace of any developments since, roughly, the turn of the century. Furtwangler evidently resumed composition where he had left off decades earlier. Not that he was unaware of what had passed in be tween: He had conducted at least three Mahler symphonies in the pre-Nazi years, and many works of Schoenberg, Bartok, Hindemith, Stravinsky, Honegger, and Prokofiev as well, and he believed that the mu sic of his contemporaries deserved active support. But his heart was in tonal music, in the great German tradition that he considered inextricably dependent on the tonal system. (Schoenberg. an equally fervent musical nationalist, sought to make his peace with that tradition by demonstrating that all his innovations were firmly rooted therein.) To understand this, we should note that the Germanic fin-de-siècle cultural milieu about which we know the most-Vienna was hardly typical; its ferment of ideas and personalities played no role in Furtwangler's youth. In Munich and Berlin, his up bringing faced southward, to Greece (his father and his tutor, Ludwig Curtius, were both noted classical archaeologists) and Italy (his fiancée, Bertel Hildebrand, was the daughter of a famous architect who kept a house in Florence). In these formative years he was exposed to all the arts in their classic manifestations: a world in which Aeschylus, Michelangelo, Goethe, and Beethoven held equal places--and Mahler, Freud, and Klimt none at all. That aspect of nineteenth-century German culture which yearned after the Mediterranean is one of its most appealing, and it was Furtwangler's spiritual home during what seems to have been an idyllic youth so it is not surprising that his musical sympathies remained rooted there.

The language of the Second Symphony is, then, conservative: a big, brooding four-movement symphony in classical forms, with clear-cut themes, developments, and returns. Its aspirations are high-in those days. you didn't write a piece lasting an hour and twenty minutes unless you planned to say something pretty weighty.

But the lengths are not covered in the leisurely, long-phrased strides of Bruckner this is more nervously active music (though a certain obsessive quality in the duple-metered scherzo does recall Bruckner). and very tightly reasoned thematically. Often, in fact, one feels that the lengths are not so much covered as filled out, that the relatively neutral expressive character of the themes doesn't bear the weight they are called upon to support by the massive structure. And the prevailingly gray character of the orchestral writing (perhaps accentuated by a rather dim recording job, especially in the first two movements) doesn't make for greater variety.

I've known this recording for about fifteen years, and come to respect much of the symphony for its professional skill. Despite all my admiration for Furtwangler as a musician, however. I cannot find it a successful piece, least of all in the final pages--victory grasped from despair--where the scoring turns conventionally grandiose.

This may not be the final word, however; though the symphony was recorded in 1951 and published in 1952, a 1954 letter to a conductor planning a performance refers to a "second conclusion." This recording was made several years after the 1948 premiere. and the Berlin Philharmonic had not played the work in the meantime, which may account for some patches of uncertain execution. In another letter to that same conductor. Furtwangler said that the recording of the symphony was "certainly in many ways authoritative, but partly a series of tempos later became faster." Tapes of later performances are in existence that might confirm this (and also clarify the matter of the "second conclusion")-but the discs are, in any case, a fervent enough brief for the work.

Deutsche Grammophon's double-fold sleeve includes a slightly abridged translation of the analysis by Peter Wackernagel that appeared on the original issue, plus a brief biographical sketch by Karla Hacker and a photo of the composer/conductor, occupying some 240 square inches of space that might more usefully have been devoted to thematic citations, more historical detail, or to a translation of Furtwangler's own "Prefatory Note to the Premiere of the Second Symphony."

-D.H.

HANDEL: Messiah (ed. Hogwood). Elly Ameling, soprano; Anna Reynolds, mezzo; Philip Langridge, tenor; Gwynne Howell, bass; Nicholas Kraemer, harpsichord; Christopher Hogwood, organ; Academy and Chorus of St. Martin in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner, cond. [Chris Hazell, prod.] ARGO D18D 3, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape: OS K1 8K 32, $23.95.

Comparison:

Davis/London Sym. Phi. SC71AX 300 From 1742 until a few days before Handel's death in 1759, there were fifty-six performances of Messiah, each determined to a considerable extent by the circumstances; portions of the score were omitted, new numbers added, others transposed to accommodate new singers, and so forth. As Christopher Hogwood, the editor of the version recorded here, says, Handel left "not one Messiah, but many." Actually, the situation is not so bad. Judicious selections from among the different versions of Messiah have been made within the last decade or so by Alfred Mann, Watkins Shaw, and John Tobin (the latter's score published in 1965 in the Halle critical edition of Handel's works now in progress).

Hogwood disapproves of these "standard performing editions," substituting the first London version, which survives only in a late-eighteenth-century copy. This is a legitimate decision, and we are grateful to this devoted scholar for letting us hear Handel's first thoughts, with several numbers that deviate from what we are used to.

But it is difficult to accept Hogwood's claim that the London version, which is not always unequivocally clear and portions of which had to be reconstructed, is better than Shaw's or Tobin's-in the absence of a definitive version, selections must be made in any event. And surely some of the additions and changes that Handel made are worth considering, as the product of second thoughts or the availability of better singers. (The "official" Tobin score prints the important variants in an appendix, the same procedure followed by Arthur Men del in his invaluable edition of Bach's St.

John Passion, which similarly survives in four versions.) Neville Marriner's performance is admirable in many respects. I have never heard a better-trained, more accomplished and ac curate boys' choir, the orchestra is first class, the general performing discipline is exemplary, and the sound is good. Yet there are some disappointing contradictions.

On the one hand, Marriner, an excellent and cultivated conductor, follows the modern enlightened way of dealing with baroque music: The tempos are bracing (even, in many instances, too fast); the proportion of the performing forces is correct and well balanced, avoiding the pyramids of sound favored by the old-line choral societies; the dynamics are tasteful; most numbers are sharp and clean, if often too fast and pointed. Colin Davis, in his remarkable recording, also displayed ample virtuosity but hit just the right degree of brilliance to bring out the incomparable charm of these pieces.

The contradictory quality comes in the self-conscious sentimentality of the solo numbers. Elly Ameling and Anna Reynolds, both very good singers, fairly tremble with emotion; some of the recitatives are really unctuous. Also, "I know that my Redeemer liveth" should not be performed, as it is here, like a French minuet, which is just as sentimental, if in a different sense, as when it is soulfully dragged. Ameling still delivers some fine singing, with her ringing high tones, and Reynolds too can sing well when she is not inhibited-interpreting "He was despised" she seems to emulate Handel's friend, the tragedienne Susanna Gibber.

who reportedly had "a mere thread of a voice." Tenor Philip Langridge is also a little awestruck but holds his own, though his is not a bel canto voice; bass Gwynne Howell is good. Both men struggle a little with the coloratura.

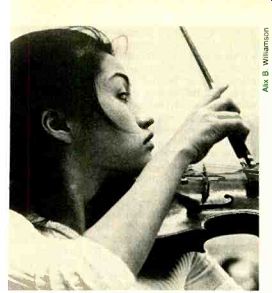

---------- Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau A new look at Ives

Finally, a word about an important aspect of the performance: the overdone embellishment, which I take to be the editor's work. In the baroque era the performer was king, but some composers, like Lully and Handel, did not permit undue liberties, and we know that in many instances the doo dads were excessive. Common as well as musical sense demands that with changed circumstances and sensibilities we should hold such embellishments to a tasteful minimum. In this recording, "I know that my Redeemer liveth" is covered with the musical equivalent of costume jewelry. (I am aware of the existence of such a sequin-studded version, contemporaneous with Handel but anonymous, but who would want to break up such a glorious melody with meaningless curlicues?) The so-called fermata cadenzas at the end of pieces or sections are, as usual, inept sallies into the musical void. Pier Francesco Tosi's famous Observations on the Florid Song (1742) should have been taken to heart. "Some." he warns, "after a tender and passionate Air make a lively merry cadence: and after a brisk Air, end with one that is doleful." Exactly this is being done these days, in the name of historical accuracy! Double-dotting, another fetishism, is also a bit exaggerated by Marriner, especially at the opening of the overture. Surprisingly in such a scholarly venture, the continuo is nearly inaudible, leaving the arias accompanied by violins and bass, which depend on replenishment by the harpsichord, bereft of harmonic support.

Still, Marriner's recording is worth considering as a supplement to Davis', both for the textual variants and for the many exquisitely performed numbers it contains.

-P.H.L.

IVES: Songs. Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, baritone; Michael Ponti, piano. [Cord Garben, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 696, $7.98 At the Fiver; Elegies Ann Street; A Christmas Carol; From "The Swimmers"; West London; A Farewell to Land: Abide with Me; Where the Eagle; Disclosure; The White Gulls; The Children's Hour; Two Little Flowers; Autumn;

Tom Sals Away; Ich grolle nicht; Feldeinsamkeit; Weil' auf mir; In Flanders Fields.

Since my October 1974 Ives discography, in which I noted that the songs represented a still largely untapped source of some of the composer's finest and most accessible mu sic, we have had Jan DeGaetani's wonderful Nonesuch disc (H 71325, August 1976) and now this collection by Fischer Dieskau. Although I cannot say that his achievement matches DeGaetani's, this is certainly a fascinating and valuable contribution to the Ives shelf. Simply to have someone of his musical background and experience deal with this literature is an ex citing and intriguing prospect.

From Ives's roughly 150 songs, Fischer Dieskau chooses a varied group of nineteen that covers the entire thirty-five years of the composer's productivity. Included are five songs not previously available on record ("Elegie," "Abide with Me," "Where the Eagle." "Disclosure," and "Weil' auf mir"); and although some of the better-known songs do appear-such as "At the River" and " Ann Street"-emphasis is wisely placed upon those that are less frequently performed.

In the performances, Fischer-Dieskau never simply takes the obvious course but shapes the pieces in unusual and unexpected ways. Indeed, my chief complaint with this disc is that the works seem over-interpreted: Fischer-Dieskau is so intent upon constantly "doing" something with his voice-articulating every possible nuance and inflection-that the music tends to get buried beneath the performance. One of the most impressive aspects of DeGaetani's disc is the way she meets the music on its own terms, neither condescending to it nor trying to make of it something that it isn't. Particularly irritating is Fischer Dieskau's habit of scooping into (or out of) notes, presumably to lend them more expressive warmth; this rarely works with Ives.

Yet there is much that is excellent about this disc. I particularly like the performances of four early settings of texts taken from European art songs (three in German, one in French), and the reading of "West London" is as beautiful as any 1 have heard. One problem in approaching this disc may simply be that we are accustomed to hearing Ives done in a certain way, by home grown voices. Fischer-Dieskau does not fall into the trap of trying to sound like a different kind of singer from the one he is, and I suspect that I will come to like these readings better as I become more accustomed to them.

All Ives lovers should welcome the appearance of this collection, offering as it does a real alternative to what is otherwise available. And while texts are provided, Fischer-Dieskau's English is consistently intelligible (though his determination to sound "American" frequently gives his voice an unpleasantly nasal timbre). Michael Ponti's sensitive accompaniments are a real plus. R.P.M.

KABALEVSKY: Colas Breugnon, Opp. 24/ 90.

Jacqueline Valentina Kayevchenko (s) Mlle. de Termes Albma Chitikova(s) Selina Nina Isakova (ms) Duke d'Asnois Anatol Mishchevsky(t) Robinet Nikolai Gutorovich (1) Giffiard Yevgeny Maximenko (b) Colas Breugnon Leonid Boldin (bs-b) Chamaille Gyorgy Dudarev (bs) Chorus and Orchestra of the Stanislaysky / Nemirovich-Danchenko Musical Theater, Georgi Zhemchuzhin, cond. [Yuri Kokzhayan and Nikolai Danilin, prod.] COLUMBIA/ MELODIYA M3 33588, $20.98 (three discs, automatic sequence).

This opera, Kabalevsky's first, was initially performed in 1938 in the composer's native city, Leningrad. Though its overture and an orchestral suite drawn from the opera gained a certain currency, the piece itself did not hold the stage. Kabalevsky puttered over it for thirty years, finally producing a revised version in 1968 (hence the dual opus listing). This second version has evidently achieved some success in the Soviet Union, and is the work recorded here by forces of the Moscow company that is descended from Stanislaysky's Opera Studio, and that has also been responsible for recordings of Prokofiev's The Duenna and Shostakovich's Katerina Ismailova.

Colas Breugnon is drawn from a tale by Romain Rolland, set in the Burgundian town of Clamecy during the 1500s. The hero, Colas, is a sculptor and carver of evidently irrepressible spirits. As represented in the opera, he is one of those in vented legends intended to embody the presumed free and noble attributes of a particular region, as well as those of the socially useful artist. In his character there are undertones of Daudet's Tartarin of Tarascon or the stage-romanticized Villon. He flouts the social order and defies the aristocracy, asserting the artist's right to expression in a society that assigns him servant status. Kabalevsky was attracted by Colas' stance as "artist of the people"--and in best Russian tradition, this means nervy satirist of the privileged classes. Colas endures humiliations, a bad marriage, plague, loss of family, and finally destruction of his entire life's work, but ends with optimistic sayings about life and a final act of bravado-the unveiling of an equestrian statue of the villainous duke, portraying him seated backward on an ass. Beneath all this runs the theme of Colas' lifelong love for Selina, who like Colas makes the wrong marital choice when young and headstrong.

The dramatic problems of the work arise in part from the difficulty of finding actions and situations suitable for showing us just why we should be captivated by Colas (villagers exclaiming "Oh, that Colas!" are not enough) or interested in his situation with Selina (they both seem merely pigheaded), and partly from a conflict in lyric stage method: The material indicates epic treatment, but Kabalevsky's compositional approach leans toward rather protracted development of choruses, monologues, and other conventional forms, carried along by expository dialogue. Neither problem is really resolved, but there is enough in the music to create at least some interest, and it is only fair to hedge judgments a bit-a recording is no way to get to know a piece like this, and it is conceivable that the Mos cow company, whose members really know how to act, makes the work entertaining and absorbing in the theater. A truly charismatic performer in the title role would do a great deal for the work.

I enjoyed the opera more as it went along, and more at second hearing than at first.

Kabalevsky's harmonic language will be familiar to anyone who has heard the conservative side of Prokofiev, and so will the sonorities, heavy on xylophone, snare drum, and muted trumpet. The first half is incessantly chattery, and though the over ture and Colas' patter song are sprightly enough and there is a pleasant song for Selina, none of these numbers do anything un predictable, and a great deal of the connecting material is dressing for characters and stage gestures that are decidedly vieux jeu to work, it would have to be inspired, not merely competent.

The writing becomes more personal and lyrically inventive in the "serious" scenes that surround the onset of the plague and the death of Colas' wife. The hero is given two monologues of some intensity, there are striking descriptive moments in the orchestral writing, and Jacqueline's death is touchingly set. The scene of a meeting be tween Colas and Selina, forty years after their youthful attraction, has some suggestive delicacy. To my ear, it is in the intimate, even sentimental side of the story that Kabalevsky does his more comfortable work; much of the "brashness" sounds like nicely crafted put-on, and the satirical commentary has little of the pungency that marks similar operatic passages in Rimsky, Prokofiev, or Shostakovich. Still, there is enough here to make me curious about a carefully cast, brilliantly directed and acted stage production, whenever that may come to light.

The performance has a great deal of vivacity--Georgi Zhemchuzhin is a real theater conductor, and the company's orchestra (supplemented, I suspect, for recording purposes) plays with considerable address, if not the utmost refinement. The men of the cast are more listenable than the women.

Leonid Boldin, an up-through-the-ranks veteran of the company, has a firm lyric bass with a trace of quick oscillation in sustained writing. He sounds quite lovely in several of the cantante passages and (like so many Slavic basses) shows off an adept mezzo voce. Much of his writing is of a parlando nature, and here he tends to sound like any above-average Russian character bass. I respected and enjoyed his work, but he did not quite persuade me that Colas is the magnetic, charming rascal he is sup posed to be, which is only to say that he does not transcend the writing.

Anatol Mishchevsky used to sing roman tic tenor leads with the ensemble (and, for all I know, does yet). He still has plenty of voice, though to judge by present evidence it is beginning to sound dry and constricted around the break and to lose some of its malleability. In what amounts to an ex tended character part, he gets off some ringing top notes and throws himself into the caricature with a will. Gyorgy Dudarev is a solid basso for the quasi-buffo part of the.

Cu.e, Yeygeny Maxirnenko a guttural-sounding baritone for the important but musically thankless role of a toady for the duke who is Colas' sexual rival.

Nina Isakova, the Selina, is an experienced MEZZO whose voice now inclines to some harshness and heaviness. She sings reliably, but at least in purely aural terms does not convey the allure intended in the music. Valentina Kayevchenko, as the wife.

does a committed piece of vocal acting, but her lyric soprano has taken on a case of thc Slavic shrills. To compare the singing of these two women with their earlier work in the Duenna recording is to have specified the sort of stiffness and wiriness that scer-..,!. to invade the vocalism of almost all Russian female singers as they move out of their youthful primes.

The sound is decent enough, though the soloists are at points rather aggros:,ivc.ly with us, and the empty-room acoustic is in evidence. The booklet includes libretto with a careful, annotated transliteration by Dr. Albert Todd and some informational background notes by Boris Schwarz. -C.L.O.

KODALY; Hary Janos: Suite.

PROKOFIEV: Li Kije: Suite, Op. 60. Philadelphia Orchestra.

Eugene Ormandy, cond. [Jay David Saks. prod.] RGA RED SEAL ARL 1-1325, $7.98.

KODALY: Nary Janos: Suite.

PROKONEV: Lt. Kije: Suite, Op. 60. Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, Antal Dorati, cond. [Raymond Few, prod.] LONDON PHASE -4 SPC 21146, $6.98. Tape:4E0 SPC5 21146, $7.95.

Comparison--same coupling: Szell/Cleveland Col. MS 7408

Neither of these conductors succeeds in projecting the quite individual satiric wit of these scores. Ormandy, who introduced the Nary Janos Suite to records more than four decades ago with the Minneapolis Sym phony, has not here captured the music's sardonic bite and wild fantasy. and the lushness of the Philadelphia Orchestra, at least as recorded by RCA, doesn't suit either piece. Both works, though brilliantly scored, need more dry -point etching to match their humor. Dorati comes closer to meeting their textural requirements, but he too lacks the necessary wit to carry them off successfully. Murcovcr, the intensely detailed Phase -4 recording dues not Baiter the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic. Dorati's performance of the Kodaly with the Philharmonia Hungarica in their set of that composer's orchestral works (London SA 2313) was in every respect better.

Among the many recorded performances of these scores. I still return to Szell's coupling: The lean sound of the virtuoso Cleve land Orchestra and Szell's rather strained sense of fun seem infinitely more idiomatic in both pieces. For the record, both Ormandy and Dorati use a cimbalom in Flory Janos and opt for the instrumental version of the Romance in Lt. Kije.

-P.H.

Law: Symphony in G minor; Rapsodie nor vegienne; Le Roi d'Ys: Overture. Monte Carlo Opera Orchestra, Antonio de Almeida, cond. PHILIPS 6500 927, $7.98.

Edouard Lalo's Symphony in G minor (1885-86), like many such minor Romantic pieces, starts out with the suggestion of a rather heroic theme, does very little with it, moves on to other themes (some quite at tractive) that likewise have little place to go, and ties its loose ends together with fairly empty dramatic flourishes. Much of the symphony sounds to me like excellent accompaniment to vocal lines that were never devised, or perhaps a curtain-raiser for a curtain that never rises. Attractive as much of the music is, it leaves me with an empty feeling.

Much more effective, despite the blatant Wagnerisms that pervade Lalo's work, are the overture to the opera Le Roi d'Ys (here, at least, one knows the curtain will go up) and the Presto from the two-movement Rapsodie norvegienne, the composer's orchestral arrangement of his violin-and-orchestra Fantaisie norvegienne. The cute folksiness of the Rapsodie's opening movement, however, does little for me.

In some of the big tutti passages, the Monte Carlo Opera Orchestra sounds quite impressive, and it is helped by Philips' big, present sonics. In more subdued passages, though, weaknesses appear, particularly a thin-toned, often flat oboe. Antonio de Almeida is good enough with the flashier material, but I do not find much cohesiveness in his approach to the symphony. -R.S.B.

MASSENET: Le Cid: Ballet Music. Lamento d'Ariane.

MEYERBEER-LAMBERT: Les Pah neurs. National Philharmonic Orchestra, Richard Bonynge, cond. [Michael Woolcock, prod.] LONDON CS 7032, $6.98. Tape: CS5 7032, $7.95.

Richard Bonynge's coupling of Les Putineurs and the ballet music from Le Cid competes with Jean Martinon's equally proficient version of the same music with the Israel Philharmonic (London Stereo Treasury STS 15051). What gives Bonynge a distinct advantage, however, is the six-minute excerpt from Massenet's late and neglected opera Ariane, one of the many ac counts of Ariadne on the island of Naxos with which the history of opera is studded.

The actual nature of the excerpt is un clear. From the note by dance historian Ivor Guest, you are led to expect the ballet mu sic, whereas the title, "Lamento d'Ariane," refers to an orchestral peroration from the third act. Some of that music is, indeed, heard here, though at least half is taken from other places in the score. Confusing though all this is. Bonynge's arrangement enables us to hear some characteristically elegant and sensuous Massenet for the first time on records. Good sound and pressing. -D.S.H.

MENDELSSOHN: Symphony No. 4, in A, Op. 90 (Italian). A Midsummer Night's Dream: Overture; Scherzo; Nocturne; Wedding March. Boston Symphony Orchestra, Can Davis, cond. PHILIPS 9500 068, $7.98. Tape: 413 7300 480, $7.95.

A disappointing record after the successful Davis/BSO Sibelius Fifth and Seventh Symphonies (Philips 6500 959, December 1975). Whether from the actual playing or from the engineering, the sound is frequently opaque and brash. Timpani are too prominent when they should blend into the ensemble, and the basses are murky when clear definition is needed thematically, especially in the Italian Symphony. Nor are Mendelssohn's dynamics correctly projected.

Certainly such sound is completely al odds with the magic and fantasy of till Midsummer Night's Dream music, and that lack of nuance also detracts from the Halian Symphony, a work that Davis' renowned affinity for Berlioz should have made especially congenial to him. I am surprised that Davis approved the release o these performances. P.1-1 MEYERBEER-LAMBENT: Les Patineurs-Sei Massenet: Le Cid: Ballet Music.

MOZART: Operatic and Concert Arias, an essay review....