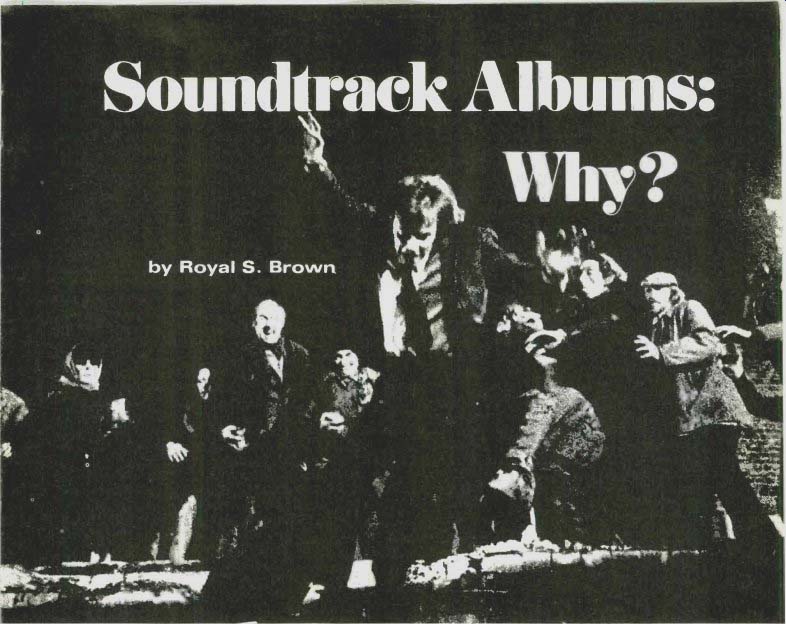

(above image) Accompanied by Alan Price's sardonic rock score, Malcolm McDowell makes his escape from the mob in 0 Lucky Man.

by Royal S. Brown

"Film music cannot be fully appreciated until it is separated from its movie."

[For information. write to Entr'acte Recording Society. P.O. Box 2319. Chicago, Illinois 60690; and Elmer Bernstein's Film Music Collection. P.O. Box 261. Calabasas, California 91302.]

IT STOOD TO REASON that sooner or later the special group of music lovers devoted to the harmonies and melodies coming from behind the movie screen would have their (lay. After years of putting up with overpriced cutouts, often dismal sound quality, and tapes made from TV showings of films whose music could not be heard in any other form, film music aficionados in the past few years have suddenly had the luxury of important reissues (especially from Angel and United Artists), some of the best recorded sound to be heard anywhere (in the RCA Classic Film Scores series and, less spectacularly, on some London Phase-4 issues), and offerings of previously unavailable but absolutely vintage wine in new bottles (RCA and Phase-4 again, plus United Artists, which is beginning a series conducted by Leroy Holmes that will offer, among other things, a complete Max Steiner King Kong).

In addition to this, the Entr'acte Recording Society and Elmer Bernstein's Film Music Collection are making available film scores both old and new and are accompanying their efforts with in formative quarterly periodicals. I could also mention some rather hair-raising piratings, at least one of which-of Bernard Herrmann's score for Alfred Hitchcock's Marnie (on clear red vinyl, yet!) is taken from the actual studio music track for the film.

But in spite of the generally more enlightened attitude shown toward film music these days, the art has yet to be taken seriously by most critics and by a large portion of the movie industry-Hollywood continues to show unflagging skill for bestowing its Oscars on the most mediocre scores. (This year was no exception; four out of five of the original scores nominated were worthy of the award; Hollywood chose the fifth.*) Why, people ask, would anyone risk apoplexy, as many film music buffs seem to do, over music written for a specific function from which, as many (including some film composers) have suggested, it has no business being separated? And how, the detractors continue, can music that is often composed to split second timing be expected to represent anything but pure hack work? For many, the old argument that film music should be seen but not heard, so to speak, still holds. One particularly uninformed editorial recently offered as proof of film music's lack of artistic viability the fact that the author had never seen a film review that mentioned the score.

Of course, the film critics' general snubbing of the musical scores is nothing to be proud of. As it happens, most critics don't talk very much about camera work either; but this in no way detracts from the often exceptional artistic quality of much cinematography, and it is just as unfortunate for us not to have stills from some of Laszlo Kovacs' fine efforts as it is not to have a recording of a major movie score by Erich Korngold. The cinema is certainly the most composite of all arts, and if the actors and directors get the lion's share of the credit (which suits the socio-theatrical proclivities of most film critics) this does not mean that the cinematographers and composers should be reduced to the rank of mere artisans working in the orbit of an artistic giant. If passive "enjoyment" of a movie seems to involve not "noticing" the music or the camera work, there is no excuse for those more deeply involved in the medium not to take into full account the separate arts, each viable in its own right, that go into making up the composite work.

[Rote/Coppola: The Godfather, Part II. The other nominated scores were Goldsmith's Chinatown. North's Shanks, Williams' The Towering Inferno, and Bennett's Murder on the Orient Express.]

Alan Price--Elmer Bernstein--Jerry Goldsmith

Film Music as Art

Although it rarely tries to break any new ground (a criterion of questionable validity in the first place), film music at its best-and often at its less than best-is a perfectly viable art form that often cannot be fully appreciated until it is separated from its movie. Certainly nobody has ever complained about the separation of incidental music from the plays it was written for. But then, most plays were not originally conceived to take musical accompaniment; most incidental music was written by composers much more famous for their concert compositions; and most incidental music has been arranged into a series of formally organized pieces.

Such is rarely the case for film scores; indeed, when they are arranged into a suite, much of the pure background music most film-music buffs wait in frustration to hear frequently is excluded.

For example, as good as it was, the lamented Mercury album (MG 20384) of Herrmann's Vertigo included none of the moody, droning passages that accompanied the scenes in which Jimmy Stewart followed Kim Novak in his car. Nor did Mercury record any of the ominous passages that included an organ in the instrumentation. Not one note of Henry Mancini's suspenseful background music for Charade is contained in the RCA recording (LSP 2755, out of print), which, apart from the excellent title theme, is filled up with mindless, pop-tune Parisiana schlock.

In a film score, even a so-called bridge can have a drug-like ability to give reality a certain color, a certain inevitability found in almost any work of art but rarely with such deliberate immediacy.

The film score is ordinarily expected to create just the proper ambience at just the right time, and rarely is it given anything resembling normal musical temporality to establish it.

While most incidental music fills empty spaces (such as between scenes) or accompanies specific scenes where music would be "realistically" present, movie music comes much closer to the function that can be performed by the orchestral accompaniment of an opera, where the over-all dramatic effect frequently arises from the juxtaposition of the developmental movement with the accumulation of diverse musical episodes. The musical unity tends to be created motivically, a technique many film composers have adopted as their own, but within a frighteningly choppy frame work. Most films have long sections without any music; when it is used, it is sometimes keyed down to the split second to fit a specific action, only to be abruptly cut off or faded out without the benefit of anything like a cadence. In fact, when cadences are added to a film-score suite, they often sound ludicrously out of place.

Creating an Atmosphere

But can such fractionalized music stand on its own? Is it true, as one composer has suggested, that you can't make an LP out of forty-nine bridges? Well, perhaps not forty-nine. But I think it is naive to assume that today's listeners are looking only for attractive themes in sustained, "coherent" musical structures. Musical temporality, harmony, rhythm, and instrumentation have by now been expanded (or annihilated) in so many different ways that I don't find it unreasonable to presume the existence of an audience capable of listening to a bridge-particularly one-for the sheer joy of its sound combinations or for its concentrated core of feeling. And certainly, composing for a specific time period is no more of a restriction than other limitations, of form, structure, harmony, etc., that great composers have al ways been able to turn to their own advantage.

Furthermore, I know of few film scores that do not contain a number of passages, even if they are eventually cut up, of a more extended nature in tended to communicate more generally a particular mood or ambience rather than to punctuate the action.

Add to all this the capital importance played by instrumentation, and you have another strong justification for the recording of film scores. Once again, it is the use of the device very much for its own sake that helps create the film-ambience immediacy. Take the type of violin glissandos heard in the scherzo of Prokofiev's First Violin Concerto, spread them out through an entire string orchestra, repeat them over and over again, and you have the gruesome background accompaniment for murder scenes in Hitchcock's Psycho. (Imagine the same sequences to the tune of, say, one of Maurice Jane's anodyne concoctions.) And when you have the mixed-genre delights of Nino Rota's part circus, part pop, part classical, and generally surrealistic scores for Federico Fellini's 8 1/2 or Juliet of the Spirits, there is matter for a high fidelity feast you'll rarely hear in its full splendor in the movie theater. But even if it is the simple piano solo or flute and harp combinations of Elmer Bernstein's To Kill a Mockingbird, the isolation of these sounds on a recording, combined with the child like beauty of the themes they orchestrate, can re create the entire emotional atmosphere of the film.

This atmosphere counts. Most film-music lovers I know are also movie buffs. Even if fans of a certain composer are delighted to hear scores by him for movies they have never seen, love for film mu sic usually begins in the movie theater or before the TV screen. Besides eliciting a general feeling for the cinematic pace and modes of presentation, the score in fact implies the voice of a Bette Davis, it is the psychological anguish of a man seeking the incarnation of a dream within a labyrinthian San Francisco. A snippet of film music can in many cases jolt the listener into reliving all or part of the picture associated with the music, affording him a kind of instant emotional replay. Because of the immediacy involved, I doubt that even the advent of ready access to films in the home will ever destroy the desire for soundtrack recordings.

With this in mind, I would like to propose that one of the best places to sell film-music records and tapes would be in the theaters. There are, no doubt, solid commercial reasons why, in our various culture emporiums (cinema and concert halls alike), we are glutted with overpriced candy and drinks, programs written by fashion designers, and souvenir Empire State Buildings rather than relevant recordings, scores, and printed information dealing with the works presented. But it strikes me that offering discs and tapes containing music an audience has just heard and very possibly liked, along with or even in spite of the film, could not only supplement profits, but also represent good public relations, particularly if sold with some kind of program material giving full credits (often cut off by curtain-closing, light-raising management) and anecdotal information on how, when, where, and why the film was made.

If not enough different musical segments have been written to justify an entire LP, the producers could take advantage of the 45 single or the EP, even for non-pop, non-title-theme scores. This is still done frequently in Europe and has been responsible for some real treasures, including Antoine Duhamel's Pierrot le fou, Georges Delerue's Le Mepris (Contempt), and Ennio Morricone's Sans mobile apparent (Without Apparent Motive). An alternative or supplement to 45 releases would be multiple soundtrack recordings such as Capitol used to make. Two Michael Winner films-Scorpio and The Mechanic-that played recently as a double feature contained excellent Jerry Fielding scores that would make an attractive coupling. (And why was none of Fielding's music for Sam Peckinpah's Straw Dogs ever recorded?) In any format-full LP, split LP, or 45-I would hope that, instead of several perhaps varied repetitions of two or three principal themes, soundtrack releases of the future could include at least a few of the bridges. Their lack is sorely missed in some of the recent RCA projects, in which we never really hear, for instance, the full breadth of Erich Korngold's instrumental inventiveness or the complete spectrum of the dramatic moods created so skillfully by a Franz Waxman or a Miklcis Rersa.

Their presence, however, is one of the beauties of the Entr'acte Recording Society's release of Bernard Herrmann's score for the Brian de Palma film Sisters. To such "complete" recordings could be added sequences written for but not used in the movie, as is the case on the Stanyan reissue of Rersa's Spellbound score (SRQ 4021).

One reason for the commercial failure of many film-music recordings is that they generally tend to get marketed with pop-music releases and promoted by people with little or no idea of what they are selling. Nor should they be sold and listed as "classical" music. It is just as ludicrous to group John Lewis and the Modern Jazz Quartet with Beethoven as it is to lump together William Walton and the Rolling Stones. Parceling out film mu sic among the pop, classical, and jazz categories would only make matters worse, particularly since there is a lot of overlapping. (How would you classify Andre Previn's Two for the Seesaw, Alex North's Streetcar Named Desire, or Nino Rota's 8 1/2, for instance?) Film music needs to be considered as an entity unto itself.

Finally, I would like to make a plea to film-music buffs to stop bad-mouthing just about everything that is being written today. Every generation creates its own excesses. I shiver to think how much more overpowering two Hitchcock master pieces-I Confess and, especially, Strangers on a Train-would be if they were not polluted by the "old school" schlock written by Dimitri Tiompkin.

And a great symphonic score can be horribly mis used by a director, as was the case with Herrmann's music for Francois Truffaut's The Bride Wore Black.

Granted, the era of Max Steiner and Erich Korngold has passed, but then, so has the era of the fresh and relatively un-jaded romanticism and heroism that justified their sumptuously romantic and heroic scores. Actors now frequently play, not Philip Marlowe, but Humphrey Bogart-either that or they give us an anti-Philip Marlowe, as in Altman's The Long Goodbye. And scores taking themselves completely seriously have no place within this new and often cynical perspective.

But the partial demise of symphonic film mu sic-and even some second-generation composers such as Rersa and Herrmann are still producing excellent scores-has not left a vacuum. If any thing, the opening up of the variety of musical gen res accepted within the cinematic medium can bring about a more nearly perfect marriage of artistic styles than was possible in the past. Try to imagine a film such as Alan J. Pakula's Klute without the excellent score (once scheduled for release by Warner Bros. and then dropped) by Michael Small, who deployed everything from rock to a haunting love theme and weird, icy filigrees and ostinatos to heighten the film's suspense and emotional content. Furthermore, there is at least one new film composer, Richard Rodney Bennett, who has taken the symphonic film score in extremely fruitful directions in such works as Far from the Madding Crowd (MGM S1E 11ST, out of print), Lady Caroline Lamb (Angel S 36940), and Murder on the Orient Express (Capitol ST 11361).

The Current Generation

The following extremely selective list of composers offers examples, presented in no particular order, of relatively recent movie music that I feel is especially successful in both the film and the disc media. I would like to stress that my omission of most of the "classic" composers, who have had numerous articles devoted to them in recent years, in no way implies anything resembling disdain.

In most, but not all, cases, I have singled out scores that have made their way to recordings at one time or another. But as everybody knows, film-music albums go out of print faster than yesterday's Top Forty, and what is $5.98 today may, cost $50 tomorrow. More and more stores, how ever, are tending to hang onto cutouts, and in many places-particularly in New York City and Los Angeles-you are just as apt to find a sought after deletion at half price or less as you are to discover it as an overpriced collector's item. Out-of-print (as of April 1975) recordings are indicated with an asterisk, while foreign LPs, which are still poorly distributed on these shores but can usually be obtained from such outfits as Peters Inter national in New York, are indicated with a double asterisk.

Ennio Morricone. Few recent film composers have been as prolific or have shown the inventiveness of Morricone, who studied composition with Goffredo Petrassi. Characteristic Morricone scores seem to synthesize the Italy of the past, as heard in his frequent churchlike chorales, with the Italy of the present, as heard in the often weird and highly inventive instrumentation, the obsessive ostinato beats or jazz rhythms, and the sometimes jarring harmonies.

Morricone had particularly good success with director Sergio Leone-the collaboration has produced one of the best film scores of the last few years, Duck, You Sucker (United Artists LA 302 G), along with Once Upon a Time in the West (RCA LSP 4736) and A Fistful of Dollars (RCA LSO 1135).

Another masterpiece is Sacco and Vanzetti (*RCA LSP 4612), while Morricone can be heard in a more lighthearted, bossa-nova vein in Metti, Una Sera a Cena (The Love Circle, **Cinevox MDF 3316).

Also strongly recommended are three recent United Artists releases, Burn (LA 303-G), The Battle of Algiers (LA 293-G), and The Big Gundown (LA 297-G). The Red Tent (* Paramount 6019), on the other hand, is much too slushy for my taste. A marvelous sampling from twenty-six of his scores can be heard on a two-disc RCA Italiana set (**DPSL 10599[2]) entitled "Ennio Morricone, Un Film una Musics," which contains such themes as Metti Violent City, The Battle of Algiers, Sacco and Vanzetti, and The Sicilian Clan.

The latter, one of his best efforts, once was avail able on 20th Century-Fox (*TFS 4209).

John Barry. Barry is probably best known for his brassy, frenetically paced James Bond scores. Per haps his best composition for the movies, how ever, is his subtle, night-jazz music for Richard Lester's Petulia, once available on Warner Bros. (*WS 1755).

The James Bond flicks would not have been the same without the Barry scores, and such United Artists albums as Goldfinger (5117), Thunderball, with its gloomy underwater music (*5132; now available only on eight-track cartridge, UA 3012), From Russia with Love (5114), and You Only Live Twice (LA 289-G) create enough atmosphere to keep you on a 007 jag for months. And United Artists now has a two-disc set offering extensive selections of Bond music (UXS 91), including the Monty Norman theme.

Francis Lai; Vince Guaraldi

In a totally different vein, Barry can be heard in the dramatic score for A Lion in Winter (exceptionally well recorded on Columbia OS 3250), which makes excellent use of an "instrument" rarely heard on soundtracks: a chorus. (David Snell's entirely a cappella choral score for Robert Montgomery's Lady in the Lake should certainly be included on an album sometime-say, one devoted to Philip Marlowe scores.) Barry's Iperess File (*Decca DL 79124) and Deadfall (*20th Century-Fox S 4208) definitely de serve re-release. The latter, the result of one of his frequent collaborations with director Bryan Forbes, contains Romance for Guitar and Orchestra written for a concert hall sequence in the film.

Nino Rota. The Rot a-Fellini combination produced some extraordinary music, and both 8 1/2 (*RCA FSO 6) and Juliet of the Spirits (*Main stream 56062) should have remained in the catalog if for no other reason than to document the fertility and vitality of the Italian new wave. Still available is the weird score for Fellini's Satyricon (United Artists 5208), which offers some of the strangest, most intriguing, nonstop sounds you're apt to hear from a soundtrack album. Likewise worth the listening are The Clowns (*Columbia S 30772), Fellini's Roma (United Artists LA 052F), and Amarcord (RCA ARL 1-0907).

Avoid at all costs Rota's gooey music for Franco Zeffirelli's even gooier Romeo and Juliet (Capitol ST 400). On the other hand, The Godfather ( Paramount 1003) has some good moments.

Three Pop-Oriented Scores. To me, one of the best rock scores ever done for a film is Pink Floyd's of ten hypnotic and psychedelic soundtrack for Barbet Schroeder's More (Harvest SW 11178). The recording of Alan Price's sardonic musical commentary for Lindsay Anderson's 0 Lucky Man (Warner Bros. 2710) documents an extremely original incorporation of music into a film. And be sides John Barry's poignant harmonica theme for Midnight Cowboy, the United Artists (5198) album contains his perfect selections of existing pop material for the film, including Nilsson's "Everybody's Talkin' " and the Elephants Memory's psychedelic "Old Man Willow."

Jerry Goldsmith. Some of Goldsmith's best scores--The General with the Cockeyed Id and Seconds--have never been recorded. Others, such as The Blue Max (*Mainstream 56081), are out of print. But The Planet of the Apes (Project 3, S 5023), with its eerie wind and percussion combinations, certainly stands as one of the most inventive and appropriate scores of the last decade, and Papillon (Capitol ST 11260) has both a beautiful title theme and a good measure of vintage Gold smith sounds, as does Chinatown (ABC 848). The Patton disc (20th Century-Fox 902) offers another good Goldsmith score and George C. Scott's famous opening speech in the film.

Vince Guaraldi. The best of Guaraldi's bouncy, nostalgic, jazzy, and otherwise delightful music for the Peanuts animations can be heard in the Warner Bros. album entitled "Oh Good Grief" (1747). It contains music for the original television series, much of which has been reused, along with a good deal of new material, in the feature-length films.

Alex North. Most film-score nuts I know would trade in their amplifiers for a chance to hear the music never used by Kubrick for 2001 (North's score was not the only one rejected), which North has apparently incorporated into his Third Sym phony. Considering the excellence of his output, we should be given the chance to hear this score in one form or another. Another loss is North's music for Cheyenne Autumn, once planned but never re leased by Warner Bros.

Of what's available, the Spartacus album (Decca 79097) represents a milestone in the Ro man-spectacular genre, although there is much more Spartacus music never recorded. And by all means get the partly jazz Streetcar Named Desire on the Angel re-release (36068), coupled with three Max Steiner suites. United Artists has just reissued North's score for The Misfits (LA 273-G).

Francis Lai. It is difficult to forgive Lai for Love Story ( Paramount 6002). But I must admit a weakness for the smooth, flowing sounds of A Man and a Woman (United Artists 5147), and for the more neurotic, mysterious Rider on the Rain (*Capitol ST 584), and United Artists has just reissued the Man-and-Womany Live for Life (LA 291-G).

Henry Mancini. A lot of what's wrong with recent film scoring has been blamed on Mancini; and there is certainly no denying that the bass-ostinato-under-jazz-theme genre established by the Peter Gunn TV music set is an overworked trend.

This takes nothing away from the fact that not only is Mancini capable of writing some of the best melodies being turned out for any medium these days, but he has also been responsible, via his scores, for much of the mood and atmosphere of pictures ranging from the tragedy of Days of Wine and Roses and Soldier in the Rain to the wit and irony of Shot in the Dark and the suaveness of The Pink Panther. (The more or less complete sound track of the latter is available on RCA LSP 2795.) An excellent selection of many of Mancini's finest movie and TV themes, if not the "background" music, can be heard on the two "Best of Henry Mancini" albums put out by RCA (LSP 2693 and 3557). Relatively complete scores currently available include The Thief Who Came to Dinner (Warner Bros. 2700) and Visions of 8 (RCA ABL 1-0231). And then there is the apparently Herrmannesque score Hitchcock rejected for Frenzy ...

Some Jazz Soundtracks. Elmer Bernstein's ominous Man with the Golden Arm, one of the first jazz soundtracks to receive wide recognition, is still available on Decca (78257). A pioneering and utterly successful experiment was done in 1958 by Louis Malle for his first film L'Ascenseur pour l'echafaud (Frantic), for which Miles Davis and four other musicians improvised a taut, bluesy score during a screening (Columbia Special Products JCL 1268). Another classic is the strange, bleak music written by John Lewis for Robert Wise's Odds Against Tomorrow (*United Artists 5061), which should certainly be reissued along with Lewis' score for Vadim's Sait-on jamais? (No Sun in Venice, Atlantic 1284).

The vogue for jazz is definitely dying out in the cinema, and when it is used these days, such as in the Charlie Parker-Sidney Bechet score for Malle's Murmur of the Heart (Roulette 3006), it tends to be "source" music. Most of the best jazz or jazz-oriented movie music on disc-including Ellington's Anatomy of a Murder (*Columbia CS 8166), Previn's Two for the Seesaw (*United Artists 5108), Art Blakey's Les Liaisons dangereuses (*Epic 16022), Bernstein's Walk on the Wild Side (*Mainstream 6083), and Leith Stevens' The Wild One (*Decca 8349)-has been long deleted from the catalogues. But United Artists has just revived Johnny Mandel's searing score for I Want to Live! (LA 271-G).

Elmer Bernstein. One of the greatest of the many sins committed in the name of the Academy Awards took place when the pseudo-Arabian pomp and bombast written by Maurice Jarre for Lawrence of Arabia, still in print on disc (Bell 5 1205), beat out Bernstein's beautifully simple To Kill a Mockingbird (* ava, AS-20). Currently in print Bernstein scores include the exciting The Great Escape (United Artists 5107), with its delightful title theme, and Return of the Seven (United Artists 5146); a recording of the original Magnificent Seven was scheduled but never re leased.

One can only regret that another Bernstein (Leonard) has written just one film score--for Kazan's On the Waterfront--a symphonic suite from which can be heard on Columbia (MS 6251).

Lalo Schifrin. Along with Morricone, Schifrin has proven to be one of the most innovative instrumentators for recent film scores. This combined with his often striking themes has helped him create some of the most intriguing and attractive movie and TV scores done in the Sixties, the best of which include The Fox (*Warner Bros. 1738) and Cool Hand Luke (*Dot 25833), not to mention the popular music for the TV series Mission: Im possible (*Dot 25831). Unfortunately, the only Schifrin soundtrack currently in print is Enter the Dragon (Warner Bros. 2727)-mediocre, but good clean fun.

--------Lalo Schifrin

Pierre Jansen. Of the many other composers I could mention to conclude this all-too-brief listing, I would like to single out a French artist who has worked almost exclusively with one director, Claude Chabrol, for whom he has scored over twenty films since 1960. Jansen's music demonstrates that the so-called "classical" film score is neither dead nor doomed to eternal Self-mimicry.

Working in a style that generally falls somewhere between chamber and symphonic music, he has ranged from the subtle atonality of La Femme infidele to the neurotic disjointedness of La Rupture (which features an ondes martenot in the instrumentation). He has produced some first-class cloak-and-dagger music as well for Chabrol's middle-period films. In the U.S., perhaps only Leonard Rosenman, in the first twelve-tone Hollywood score, The Cobweb (*MGM E 3501 ST), has written film music with a similarly sophisticated "classical" orientation.

If Jansen's name remains obscure, it is because, incredibly, not a single note he has written has been recorded, as far as I know, and because Chabrol's beautifully crafted and often brilliantly original films have, like many European movies, been getting rotten distribution, although the situation seems to be improving. So deeply is director Chabrol committed to music (he once said that, if he hadn't become a film director, he would have been a conductor), plans apparently exist for a Jansen opera based on a Chabrol libretto. I can't wait!

-------------

( High Fidelity magazine, Jul 1975)

Also see:

Karajan: Encounters the Second Vienna School--David Hamilton--DG offers a four-disc set

Re-climbing Everest (remastering recordings of the old Everest label) (Jan. 1990)