by JOHN EARGLE

One of the promises of the CD revolution that is now being fulfilled in abundance is the reissue of the best of the various "golden ages" in phonographic history. In many cases, we are hearing these old recordings as they've never been heard before, with more clarity than we'd ever thought was in the grooves or master tapes. The major companies are scouring their vaults, looking for their best and earliest source material, and transferring it to digital formats for further processing or direct transfer to Compact Disc.

Philips is doing something that is rare for a major label: They have gone beyond their own vaults and are rereleasing some of the classic recordings of the old Everest label, which thrived as a division of Belock Instrument Corp. during the '50s and early '60s.

Most readers of Audio are aware that Associate Editor Bert Whyte was responsible for the technical side of these recordings. In its day, Everest was celebrated for the quality of its recordings, and only on rare occasions did the major labels match what Everest did on a routine basis. As an engineering student during the late '50s, I was enamored of their two-track reel-to-reel tapes and had amassed quite a collection of them, expensive as they were. For those without a tape player, there were the noisy Everest stereo pressings, which gave little indication of what was really on the master tapes.

Later, when I came to know Bert Whyte, I had the privilege of hearing his own proof copies of the carefully prepared tape duplicating masters. These gave me an even better idea of how truly remarkable the recording technology was.

Whyte pioneered the use of three-track magnetic recording on 35-mm film. With a speed of 90 feet per minute (18 ips), track widths of one-quarter inch, and a very thick base material, the medium was extremely quiet, had virtually no print-through, and exhibited excellent time-base stability.

Not all Everest recordings were made with 35-mm film, and standard 15-ips, three-track half-inch tape was also used. In the early '60s, Belock decided to get out of the record business, and the company was sold. Its image receded, and pressing quality got even worse.

The legend remained, however, and record and sound buffs have never forgotten Everest's original accomplishments. Bert Whyte's greatest contribution was his ability to emphasize the sonic values of rich modern scoring without getting in the way of the music or detracting from it in the least. Over 30 years later, this remains a worthy goal for all recording engineers.

For their first group of Everest reissues, Philips has picked five examples of the 35-mm technology, and they have processed them with the remarkable NoNoise system developed by Sonic Solutions of San Francisco, which is the culmination (at least for now) of the long search for systems that can remove noise already present in recordings.

Such systems have nothing in common with the dbx, Dolby, and other noise-reduction systems that attack noise before it becomes a problem, by compressing the signal during recording and expanding it during playback. In this way, the signal can be maintained well above the noise floor of the medium during recording; playback processing restores the program's original dynamics while pushing the noise floor lower.

Once a noisy recording has been made, there are limited options for quieting it. Over the years, static techniques such as low-pass filtering and removal of discrete noises through tape editing and dynamic techniques such as program-directed filtering have both been used. Their effectiveness has varied, depending on the nature of the program, but in general, it is felt that any kind of filtering removes music at the same time it removes noise.

Many years ago, Harry Olson of RCA developed a novel method for removing noise from recorded program material.

His technique was to divide the spectrum into octave bands by way of sharp filtering. Within each band, he established a user-variable noise-floor threshold. Any signal below the threshold could be defined as noise and be "squelched." When the several bands were recombined through further filtering, the noise was all but gone and the music left virtually intact.

In 1984, at the AES Conference on the Art and Science of Recording, Roger Lagadec, then of Studer Revox, demonstrated a digital version of the Olson scheme, this time using 256 discrete frequency bands. Although the system was demonstrated in mono, the results were impressive. We could hear that the threshold of noise, if set too high, could affect the ring-out of reverberation. It became obvious that good musical judgment had to be exercised to produce acceptable results.

With cyclical interferences such as hum, buzz, and the like, it is possible to sample the interfering signal, duplicate it, and return it in opposite polarity, achieving a virtual cancellation without affecting the music in the least. The NoNoise process accomplishes all of this. In addition, it can detect discrete disturbances, such as clicks, and replace them with a replica of previous cycles of music waveforms so that absolute playing time is not affected.

Digital technology can do all of this with the appropriate programs. The processes are not cheap, and good ears must be constantly at hand to ensure that good taste prevails. It is always wise to leave a little of the noise floor audible. After all, some of that noise was in the original venue.

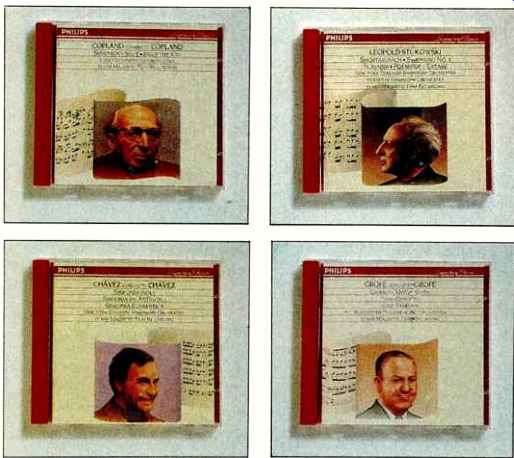

I have listened to four of Philips' Everest reissues made with NoNoise, and the listening is almost magical. With the background noise all but inaudible, it is easy to imagine that you are hearing the "line out" of the recording console. The sound may be quieter than what the recording crew heard when they played back the masters, and details of the soundstage become remarkably clear. One also hears a characteristic of the day, the sound of the early Neumann U-47 microphones, with their relatively undamped high-frequency peak. Nothing bad, but not a match for the ultra-smooth microphones of today. Let's look at the four discs I have auditioned: Leopold Stokowski is represented by the Shostakovich Fifth Symphony, performed by the New York Stadium Symphony Orchestra, and Scriabin's "The Poem of Ecstasy," performed by the Houston Symphony Orchestra (422-306-2). The Stadium Orchestra was in reality the New York Philharmonic, which at the time was under contract to Columbia (now CBS) Records and could not record for other labels under its own name. The recording was made in the eighth-floor ballroom at Manhattan Center in 1958, and it stands up well today. The immediate ambience and "bloom" of such rooms as the one in Manhattan Center are rare in the United States, but such spaces are highly valued in England and Europe and account for the sound heard on many imported recordings.

After many years of inactivity (due to changing of hands and unfortunate carpeting), the old Manhattan Center ballroom is once again coming into its own as a recording venue; its carpet is now covered, on request, by thick sections of particleboard, thus restoring the original reverberation. The Houston Symphony recording, dating from 1960, does not come off as well, mainly due to acoustics.

The music of Mexico's Carlos Chávez, conducted by the composer, also features the New York Stadium Symphony Orchestra recorded in Manhattan Center in 1958 (422-305-2). The program consists of Sinfonía India, Sinfonía de Antígona, and Sinfonía Romántica, all richly scored works making use of native coloristic elements--exotic music for exotic tastes.

Copland's Third Symphony and "Billy the Kid" Ballet Suite are conducted by the composer with the London Symphony Orchestra (422-307-2). The recording venue was Walthamstow Town Hall, near London, a room famous for recordings for four decades. Normal seating is removed, and the orchestra is placed toward the center of the room. Just a few microphones are needed to pick up the ensemble, with an assist from the dense array of early lateral reflections in the space. These 1958 performances hold their own with any of today.

The Eastman Theater in Rochester, New York was the venue for Ferde Grofé's " Grand Canyon" Suite and Piano Concerto, also conducted by the composer, with pianist Jesús Sanroma and the Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra (422-304-2). The recording was made in 1960. The Eastman Theater is a quirky room, large and with particularly disturbing reflections from the fascia of the balcony and loge.

Under such conditions, a fairly close-in approach to the orchestra was dictated. This works quite well on the " Grand Canyon" Suite, with its detailed scoring and reminiscences of studio writing.

Grofé certainly knew what he wanted and brought out the best in the Suite.

The Concerto is a lesser work, and even the consummate virtuoso Sanroma cannot carry it off.

The fifth release in the series will be Stravinsky's "Ebony" Concerto, featuring Woody Herman, plus "Petrouchka" and Symphony in Three Movements--all with Eugene Goossens conducting the London Symphony Orchestra. I look forward to a hearing.

As I survey these four releases, it becomes apparent that the best current recording techniques, as applied to classical orchestral recording, have nothing over what was done 30 years ago. Such men as Bert Whyte, RCA's Lew Layton, Kenneth Wilkinson of British Decca, and a handful of others set down the rubrics for those who followed.

Everest has truly been re-scaled, and the view is loftier than ever.

(source: Audio magazine, Jan. 1990)

Also see:

Audiophile Recordings: Polished Antiques (Sept. 1982)

Engineering the Boston (Aug. 1990)

The Audio Interview: Avery Fisher--The Gift of Music (Sept. 1990)

============