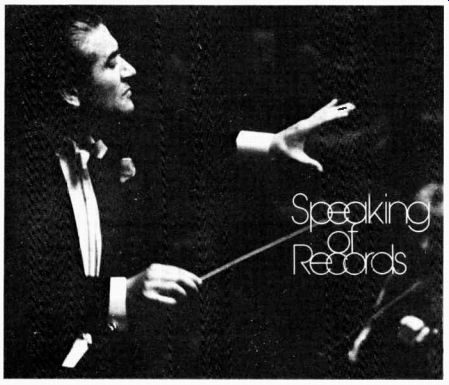

The Conductor Who Refuses to Record

by Paul Moor

"RECORDINGS? The destruction of music!" The vehement speaker was the Romanian-born, stateless conductor Sergiu Celibidache, long resident in Paris.

Celibidache (pronounced chay-lee bee-DAH-kay), now sixty-three, recently hurled these thunderbolts of opinion at Dr. Klaus Lang, a young staff member of the radio station Sender Freies Berlin: " You don't listen to recordings in the same acoustics as those where they were made. Acoustics have a living function, for in stance, in determining tempos. You cannot take a tempo suitable for a hall in Berlin and transfer it to a hall in London. With short reverberation you have to pick up the tempos, with long reverberation you have to take care the tempo doesn't cause musical values to overlap, causing frightful con fusion.

"You yourself are an opponent of recordings, but you do not know it, for you are deaf. You think you are not deaf, because you hear me speaking.

You do not hear what really matters.

A microphone amplifies certain over tones and cancels out others. There may be interesting sounds on a record-from a quite unmusical stand point. What, in a recording, is genuine?" Although Celibidache demands and gets high fees, poses uniquely demanding conditions, and picks and chooses the few engagements he accepts, he has remained less widely celebrated than a number of less formidable conductors whose names regularly appear on record labels. A student of music in wartime Berlin after earlier studies in mathematics, philosophy, and musicology, he made a sensationally impressive debut with the Berlin Philharmonic soon after the war, during the period when de-nazification proceedings had removed Wilhelm Furtwangler from his post. In 1947 Celibidache became that orchestra's chief conductor.

Berlin still reverberates from the imprecations he fired off when he departed in 1952, most of them aimed at Furtwangler, a man never noted for favorably regarding gifted young rivals. Celibidache concedes his own "combative" nature. In recent years in Berlin one has heard that another conductor, Herbert von Karajan, has had three esteemed colleagues on his blacklist whom he has allowed no contact whatever with his manifold enterprises: Celibidache, Bernstein, and Carlos Kleiber.

Celibidache fans tend to idolize him, and he and many Berliners still carry on a mutual love affair even with their Prince Charming long since banished. Not only Berliners treasure the two lone recordings he made long ago before the scales fell from his eyes and ears: Mendelssohn's violin concerto (with Siegfried Bornes) and Scotch Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic (Electrola HZEL 700), and the Tchaikovsky Fifth with the London Philharmonic (German Decca 641909). Celibidache's distaste for recording carries over in his attitude toward radio concerts. " I do not give radio concerts," he says, "I give concerts. If the radio wants to broadcast or tape them, I cannot say no, otherwise I should have to die or find another profession. But if I had the money and could pay for the concert without help from the radio, naturally I should prefer that." He goes on to explain his method of interpreting music: "Analysis is the essential means of preparing an interpretation, but an analysis most conductors ignore completely: phenomenological analysis.

"Let us take, say, a C sharp. The succession and the combination of the intervals that have led to that C sharp are contained in that C sharp, and so is the future of that C sharp. And so I must feel, must sense, the past and the future. But where? In the simultaneity-that is, in what the philosophers call the 'becoming conscious' and not in the ' being conscious.' "On the one hand, what is the material that I may not, cannot, interpret? And what is the relationship between what puts the material into motion and the human consciousness? "What, after all, is music? Movement! What moves? Nothing more or less than our consciousness. One can feel music without hearing tones. The farmer who has nothing more in mind than to express his happiness or his mood in the morning-he sings, but that's not notes, not a score, nothing.

That is a form of dynamics that ex presses itself." Celibidache's demands for rehearsal time make orchestra man agers blanch. " I concentrate now on two orchestras, in Paris the National and in Stuttgart the South German Radio Orchestra," he says [since this interview, Celibidache has severed his connection with the former]. " In Paris I have twelve rehearsals for a concert, in Stuttgart fourteen. The number of rehearsals depends upon the quality of the orchestra, but not in the way you might think. The better an orchestra is, the more you must rehearse with it, for it offers you more possibilities. In a mediocre orchestra, the flutist, for example, can play in only three ways instead of three hundred.

In such a case I expect the orchestra to play together-a little piano, a little forte-and that's that. But if it offers me five hundred different possibilities of producing tone, then which is the best for combining the flute with, say, the bassoon? That is a question of taking time.

"I have conducted the Vienna Philharmonic, a mediocre orchestra. It has one single mezzo-forte--they cannot at all understand structure, the natural order of instruments, sound. And, in addition, no interest. Just imagine, this is an orchestra that makes cuts in Mozart, legalized for all time. In Mozart! Imagine! And such an orchestra re cords twenty Mozart symphonies with a big conductor who does not once open his mouth! That's music to day for you. Not for me. I have no time for such an orchestra." How does he view the younger emerging conductors? "There is not one new conductor who still under stands music or who can grasp the difference between notes and music.

None! They are all note-chasers, and music has nothing to do with notes.

Notes are a vehicle for the transport of a substance. The substance materializes itself through this vehicle, but it is not in the notes. I find myself floating in a bath of musical ignorance such as the world has never known before.

We have no more technicians today." "Why is a conductor's 'personality' supposed to be decisive?" Celibidache continues. " It is a precondition that a conductor have the authority to carry something over to the orchestra, but nobody has asked himself what [to] carry over. Vulgarity! Triviality! "What does the world know about the composer's intentions? For 150 years it has proven that it has under stood nothing. Under Wagner's baton, the Siegfried Idyll lasted thirty minutes, under Bernard Haitink's twelve.

I assume that Wagner knew better. A scandal! And what a scandal Knappertsbusch was! Everyone spoke about his ' broad' tempos-that was not broad tempos, that was nonmusic to the nth degree! He had absolutely no sensitivity to the relationship be tween vertical pressure and horizontal flow, and that, after all, makes all the difference in music. What did Furtwangler leave us in the way of true music? You can't take over one single bar. Who today can realize the composer's intentions? Certainly not Mehta or Maazel or any of those others.

"Urn Gottes Willen, I do not speak of myself. I started out the same way. I do not say now that I can do it. I say only that what I hear is not music. You must tell me if for you what I make is music." And thousands of Celibidache fans in various countries do, vociferously.

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1976)

Also see:

Classical: Milstein's Bach...Die tote Stadt ... Beethoven choral works