reviewed by: ROYAL S. BROWN; ABRAM CHIPMAN R. D. DARRELL PETER G. DAVIS SHIRLEY FLEMING ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE CLIFFORD F. GILMORE HARRIS GOLDS MITH DAVID HAMILTON DALE S. HARRIS PHILIP HART PAUL HENRY LANG ROBERT LONG ROBERT C. MARSH ROBERT P. MORGAN CONRAD L. OSBORNE ANDREW PORTER H. C. ROBBINS LANDON J OHN ROCKWELL PATRICK J. SMITH; SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

------ Nathan Milstein-the Bach sonatas and partitas colossally

done.

AUBER: Marco Spada. London Symphony Orchestra, Richard Bonynge, cond. [Michael Woolcock, prod.] LONDON CS 6923, $6.98.

Marco Spada is another in the long line of mid-nineteenth-century ballets that, important in their time, have long since vanished from the scene, leaving behind merely a name and a shadowy reputation. By res cuing the scores of works like this from oblivion, Richard Bonynge has enriched our knowledge of ballet history, while at the same time restoring to currency a lot of unpretentious, delightful music.

Marco Spada, a three-act work produced in 1857 at the Paris Opéra, is remembered today chiefly because with it Joseph Mazilier, the choreographer, provided a show case for two distinguished ballerinas, Carolina Rosati and Amalia Ferraris-the former an expressive actress, the latter a brilliant technician. The complicated story deals with the difficulties in the path of true love and the part played by Marco Spada, a bandit chief, in smoothing them out.

Though Auber had composed an opéra comique on the same subject five years be fore, his score for the ballet is a pastiche de rived from several of his own works. It is unfortunate that no act-by-act synopsis has been provided with the recording. Listeners who don't own Cyril Beaumont's Complete Book of Ballets will have a hard time relating the music to the scanty story given in Ivor Guest's liner notes, though there are some self-evident pointers-like the allusion to Marco Spada's profession by means of an arrangement for trumpet of " Voyez sur cette roche" from Fra Diavolo.

Auber's music is lively and varied in mood. Both the tunes, which are plentiful and often irresistible, and the orchestration, which is wonderfully deft, betray the unmistakable influence of Rossini. At the same time, one can see what Offenbach took by way of vivacity, wit, and clarity from French opéra-comique. (Balletomanes might be interested to learn that the music for Victor Gsovsky's Grand Pas Classique, currently in the repertoire of the American Ballet Theater, is derived from Marco Spada.) Bonynge, at his best in nineteenth-century ballet music, obtains a spirited performance from the excellent London Sym phony. Good, spacious recorded sound, though each side contains more than thirty minutes of music.

One puzzling detail about this issue: The jacket shows, without any identification, Lucille Grahn and Jules Perrot in a scene from the latter's ballet Catarina, produced in London in 1846, with music by Cesare Pugni. To my knowledge, the only thing it has in common with Marco Spada is that both ballets feature a bandit.

D.S.H. BACH: Art of Fugue. For a feature review, see page 76.

BACH: Sonatas and Partitas for Solo Violin (6), S. 1001 - 6. Nathan Milstein, violin. [Werner Mayer, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 047, $ 23.94 ( three discs, manual sequence). Sonatas: No. 1, in G minor, S. 1001; No. 2, in A minor, S. 1003; No. 3, in C, S. 1005. Partitas: No. 1, in B minor, S. 1002; No. 2, in D minor, S. 1004; No. 3, in E. S. 1006.

Comparisons: Szeryng Odys. 32 36 0013; DG 2709 028 Novotny Supr. 1 11 1101/3

In a July 1974 MUSICAL AMERICA interview Nathan Milstein talked about recording the Bach solo sonatas and partitas for the second time, in his seventies: " I last recorded them twenty years ago. This time I must make them as good as I can. I will never do them again." He has done them colossally.

They were wonderful the first time: brilliantly lucid, warm, and musically penetrating. They always stood, among the gathering throng of fresh versions by various artists, as pillars of sanity and good taste, and they were marked by that sheen of sophistication characteristic of Milstein and paralleled, in my opinion, only by Henryk Szeryng. The new performances are even better than the old, having shed, like un wanted fat, the occasional juicy portamento and having grown just perceptibly more cohesive and tighter in line. The cohesiveness has nothing to do with tempo-the Preludio of Partita No. 3, for example, is a bit slower in the new version than the old, but it breathes more, and the faultlessly terraced dynamics keep every phrase precisely in place. In his handling of dynamics alone, Milstein reaches what must be a new plateau in this literature. (The Allemande of Partita No. 2 is another case in point, but there are many.) In considering any version of the sonatas and partitas one is always reminded that the faster movements present one set of performance problems and the slow movements quite another. In the doubles, allegros, preludes, and even the Gigue of Partita No. 2-all those movements that run along in unceasing eighth- and sixteenth note patterns-any artist of stature is able to lean with the right amount of stress on the pivotal note of the phrase without breaking the pulse or distorting the written time value too severely. (Szeryng achieves this emphasis more by accent than by rhythmic stress; Milstein achieves it by holding onto the note a hairsbreadth past its allotted time.) The slow movements and the fugues, so incredibly complex in their subdivisions of the beat, are something else again. If one wanted to pick a quarrel with Milstein, one might point to the Largo of Sonata No. 3, in which he departs with utter aplomb quite radically from the time values as written, giving to sets of even sixteenths a lilt that makes them sound almost like sets of triplets. Or, in the Adagio of the same sonata, where the texture suddenly thins out at measure 34, he allots breathing space between phrases that some violinists might link more closely. But it is hard to object strenuously to such small liberties, for they are fruits of wisdom and of an enormous and justified self-confidence. The music pulses with life, and only once-in the Fugue of Sonata No. 3-does Milstein seem to me to lose the underlying beat.

The Chaconne is monumental-less silken than Szeryng's and absolutely fire breathing in such passages as the first section in thirty-second notes. The piece as a whole will leave you limp. I found myself surprised, though I probably shouldn't have been, at the amount of passion Mil stein can summon, for all his social graces; the old Chaconne showed this aplenty, and the new edition hasn't lost a single volt.

When I last had occasion here to review new releases of these sonatas I was much impressed with the Supraphon set by Bretislav Novotny (March 1975). It is poles apart from Milstein's: craggy, deliberate, granitic. Novotny's severe viewpoint leads him to chisel every note out of stone. Some times, in his austere intellectualism, he lets a long lyric line break up a bit in order to do justice to an individual note group within it. Milstein views the whole fabric at longer perspective. In his balance of cerebration and sensuousness, he manages to get the best of both worlds. S.F.

BEETHOVEN: King Stephen ( incidental music), Op. 117; Choral Works. Ambrosian Opera Chorus; London Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas, cond. [ Paul Myers, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33509, $6.98.

Ouadriphonic: MO 33509 (SO-encoded disc), $7.98. Choral Works: Meeresstille und glückliche Fahrt, Op. 112; Elegiac Song, Op. 118; Opferlied, Op. 121b (with Lorna Haywood, soprano); Bundeslied, Op. 122.

Like most great composers, Beethoven wanted to write operas, and the period 1810-14 is when the Beethoven operas that we might have had--Macbeth, Brada mante, The Ruins of Babylon, Attila, The Return of Ulysses, Romulus and Remus--were considered. This is also the time of the revised Fidelio and of the theater music for Egmont, King Stephen, and The Ruins of Athens.

Beethoven's flair for theater music is apparent in the Egmont score, even when the music is detached (or semidetached) from Goethe's play. It is apparent, too, in King Stephen. We still lack a complete recording, but Michael Tilson Thomas gives us more of the music than figured in the Schdrizeler/Turnabout and Oberfrank/Hungaroton discs. His omissions are of No. 5, a brief melodrama during which Stephen seats his bride Gisela on the throne beside him, and twelve pages of melodrama in No. 8, before the final chorus. The text of Kotzebue's King Stephen is so short-it is a celebratory tableau with music rather than a play-that it might perhaps have been possible to include it without running over the side (which, as it is, lasts 23 1/2 minutes). Even if the speeches between numbers were abbreviated, it would be good to have the speeches with music-and, at the least, a full libretto, which would tell us, for ex ample, that the andante maestoso crescendo of No. 7 accompanies a tableau of a fine mist dispersing to reveal the town of Pesth.

The performance is first-rate: bold, ar resting, and theatrical, from the first clarion calls to attention from the trumpets and the horns. Thomas seems to have got exactly the right timbres from the LSO, which plays in a very direct, candid, and "classical" way-plenty of punch, but no forcing of the tone and no Romantic fatness. The pretty "bridesmaids' chorus" all'ongarese goes with great charm; the graphic and picturesque qualities of the music are vividly presented. My only quibble is at the mannered détaché of some of the choral singing, when, in an effort to ensure clean articulation, the Ambrosians seem to be imitating the pizzicato of their accompaniment.

King Stephen is a score to value. So is The Ruins of Athens, which fills the other side on the Turnabout and Hungaroton discs. The choral works on the other side of the new Columbia are less remarkable, but at any rate three of them fill a gap in the catalog. The Elegiac Song-which should surely be done by four voices, not a chorus-needs more sostenuto, more legato singing than it receives here. The Opferlied is somewhat in the vein of Elisabeth's prayer in Tannhauser. The Bundeslied is rather a bore-four square identical verses, with wind accompaniment, and then a fifth with protracted cadences that the first clarinet festoons with arpeggios.

Becalmed Sea and Prosperous Voyage is also available in a Boulez performance (Co lumbia M 30085), as a filler to the Fifth Symphony; another, by Leitner, was until recently available in one of DC's Beethoven Edition boxes. (I amend the customary English translation of the title because, as To vey put it: " Calm Sea misses the point and suggests the poor landlubber's sine qua non for a prosperous voyage.") The "becalmed" section comes off none too well, because the Ambrosian sopranos' high A's are rather scrawny and the choral chording is not always precisely tuned. But Thomas is very good at raising the wind-first freshening little zephyrs and then a good, stiff blow that brings the vessel and its crew bounding exultantly into port.

Texts and translations are provided, but not in parallel columns. Three Kalmus pocket scores, Nos. 433, 439, and 1019, contain all the music. A.P.

In quad: The sound is reasonably spacious without being obtrusively (or memorably) quadriphonic. R.L.

-- Michael Tilson Thomas A Beethoven score to value.

BLOW: Coronation Anthems; Symphony Anthems. Soloists; King's College Choir, Cambridge; Academy of St. Martin-in-the Fields, David Willcocks, cond. ARGO ZRG 767, $ 6.98.

If Handel's magnificent but peculiarly English anthems are somewhat removed from us, even when performed by a good mixed choir, how much more so the Restoration anthem, with its boys, countertenors, and falsettists. John Blow (1649-1708) was an influential composer of modest and very un even talent. Among his many routine and lifeless works there are some fine songs and motets, a nice masque, and the first English opera, Venus and Adonis. The anthems re corded here are not outstanding works; Blow being basically a lyricist, the large form and the ostentatious splendor of the coronation anthem, so congenial to Handel, did not suit him. Though there are interesting moments, on the whole one's attention is soon exhausted.

The performances, however, must share the blame. The ensemble of boys, countertenors, and tenors, with lesser roles for the basses, is not a ravishing one, but I has ten to say that the boys of the King's College Choir turn in by far the best performances. Boy trebles and altos are often glassy and innocently expressionless, but how glorious the youngsters sound here compared to the voices, lacking both color and resonance, of the countertenors and the cautious tenors. Caution (or is it a tradition unknown to us?) characterizes the whole production. The lovers of "historical accuracy" à outrance will have a field day. but we commoners are left longing for a little substance, color, and bite. P.H.L.

BRAHMS: Concerto for Violin, Cello, and Orchestra, in A minor, Op. 102.

SCHUMANN: Fantasy for Violin and Orchestra, in C, Op. 131. Ruggiero Ricci, violin; George Ricci, cellot; New Philharmonia Orchestra and Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra', Kurt Masur, cond. [Robert Auger, prod.] TURNABOUT TV-S 34593, $3.98.

Comparison

Brahms: Ferras, Tortelier, Kletzki Sera S 60048 The major attraction here is the filler work, Schumann's rarely heard fantasy for violin and orchestra, a late-period composition full of brooding intensity but offset by enough airy brightness and humor to keep it memorably afloat. Those with an aversion to late Schumann are advised that the writing is at times quirky, that develop mental passages are typically cryptic (some will say "disjunct"), and that Schumann's scoring frequently favors somber mass over detail. Still, the fantasy is a stronger work than the D minor Violin Concerto, and the solo line cuts through the thick symphonic backdrop with more effectiveness than is sometimes the case with the two Konzertstücke for piano and orchestra. Ruggiero Ricci's clear, rather acerbic, knife-edged style helps in that respect, and his unsentimental phrasing is just what the piece needs. Kurt Masur and his distinguished Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra provide memorable, granite-like solidity in the best "traditional" manner. (The fantasy is most often heard in an edition by Fritz Kreisler; in the absence of any indication from Turn about to the contrary, I assume that Ricci uses the original version.) There is nothing actively wrong with the Brahms double concerto, though the soloists are a bit wiry and, in the slow movement, a shade sentimentally hairpin prone. The tempos, slow to begin with, are not ideally sustained; phrasing tends to choppiness. The New Philharmonia plays well but doesn't match the solidity that Masur gets from his own orchestra in the Schumann. The more sonorous Seraphim version by Ferras, Tortelier, and Kletzki, taken at similarly deliberate tempos, is more of a piece interpretively, and indeed it holds its own against the full-priced versions.

Get this well-recorded disc for the Schumann, though; you will find the fantasy well worth knowing. H.G.

Brahms: Sonata for Piano, No. 3, in F minor, Op. 5; Rhapsody in G minor, Op. 79, No. 2. Bruno Leonardo Gelber, piano.

CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CSQ 2084, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc). There is little evidence here of the affinity for Brahms that the Argentine-born Gelber showed in his Odeon recording of the First Concerto. The structure of the sonata is constantly weakened by spasmodic little agitations and holdbacks. The line usually goes limp at lyrical second-theme groups, and the commanding material of the opening sounds thin and percussive. There are occasional hints of imaginative voicing, but for the most part this is a petulant, fidgety reading of music that must be big and free-wheeling.

I see no point in recommending this disc with superlative accounts of the sonata readily available from Arrau (Philips 6500 377), Rubinstein (RCA LSC 2459), and Curzon (Stereo Treasury STS 15272). At budget price, the latter is an outstanding bargain.

H.G.

CHOPIN: Waltzes (18). Aldo Ciccolini, piano. SERAPHIM S 60252, $3.98.

This edition of the waltzes would be out standing even at full price. Ciccolini, a superbly aristocratic artist, strikes an almost perfect balance between metric regularity and caressing leeway. He commands a fastidious, silken legato and is capable of a ravishing pianissimo, which he uses here appropriately and often. His fingerwork glistens, and the difficult passagework has a brilliant, slightly dry. sparkling quality.

Most of the tempos tend toward briskness.

As a result, the music sounds airborne but never rushed. Along with the elegance and facility go many sparks of drama and memorable individual turns of phrase; note, for instance, the wide dynamic range and incisive little spurts in the E minor Waltz, No. 14 of the standard set.

Ciccolini plays four of the five posthumously discovered pieces included in the excellent Henle edition (omitting only No. 17) and follows the Henle sequence, which places two of the added pieces before No. 14. Like Abbey Simon (who recorded all nineteen waltzes on Turnabout TV-S 34580, November 1975), Ciccolini sticks basically to the Fontana text in those waltzes for which Henle gives both Fontana and the substantially different manuscript version.

The sound is bright and glistening. Altogether, a wonderful record, and one to set alongside those of Lipatti (Odyssey 32 16 0058), Haas (Epic and Mercury Wing, deleted), and Rubinstein (RCA LSC 2726). Si mon, while not quite in this class, is a wor thy contender if you desire all nineteen waltzes. H.G.

DALLAPICCOLA: Il Prigioniero. For a feature review, see page 78.

DEINISSY: Orchestral Works, Album 6: La Bete à joujoux; Printemps. Orchestre National de l'ORTF, Jean Martinon, cond. [ René Challan, prod.] ANGEL S 37124, $6.98 (SQ encoded disc). Comparisons: Ansermet (same coupling) St. Tr. STS 15042 Boulez ( Printemps only) Col. M 30483

This final disc in Angel's successful traversal of "The Orchestral Music of Debussy" is not strictly "orchestral Debussy," but then nobody has come up with a satisfactory definition of just what does constitute Debussy's "orchestral works." The symphonic suite Printemps was originally a choral piece by the then twenty-five-year old composer, which won a Prix de Rome but was subsequently destroyed by fire; it came into its present form in 1913 through the ministrations of Henri Busser. In that same year, Debussy finished the two-piano sketches of his children's ballet La Bone à joujoux but somehow left the orchestration to be completed by André Caplet.

No matter such quibbling. All's well that ends well, and Martinon's series certainly does, with a worthy rival for Ansermet's disc of these charming and effectively scored works. The latter now costs only about half as much as the new record, but the 1958 sonics, though perfectly clear, are in truth a bit dry and boxy. Angel's sound is brilliant and spacious, with quite impactive bass transients.

Martinon presents La Boite à joujoux with a vividness of characterization wanting in Ansermet's more reserved and steadily controlled interpretation. Yet the latter has a jeweled subtlety, a lilting reticence that is enduringly magical, and the Suisse Romande oboes are more plaintive than their Parisian counterparts.

In Printemps, however, Martinon is decisively most successful in capturing the frequent shifts of motion and thus expression.

Boulez (coupled with the Nocturnes and the clarinet rhapsody) is even more rigidly metronomic than Ansermet, though he does bring a degree of point and swagger to the final dance tune that neither Ansermet nor Martinon matches. Also, the Columbia version is played with the most sensitive ensemble discipline and balance of the three; note, for example, the doubled flute and piano of the opening. On Angel, some of the more climactic textures are a bit blurred in the live ambience of the Salle Wagram. You may not, in short, find any of the three the perfect realization of the music, but neither can you go far wrong. A.C.

Delius: North Country Sketches; Life's Dance; A Song of Summer. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Charles Groves, cond. [John Willan, prod.] ANGEL S 37140, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

North Country Sketches is a de facto Four Seasons, conveying to this hearer the individual ambience of the times of year even more vividly than the corresponding works of Vivaldi, Haydn, Milhaud, Glazunov, et al. The first section, "Autumn-the wind soughs in the trees," is set for the darker colors of the orchestra and keeps modulating downward, with outbursts of sobbing and wispy melodic disembodiments.

The second section, "Winter Landscape," is a series of bleak pronouncements in icy, block-like harmonies against a mockingly simple four-in-a-bar accompaniment.

"Dance" may not explicitly mention summer, but its bright and delicate pastel shades and the lazy mazurkalike rhythm leave little doubt of the warm indolence in the air. The finale, "The March of Spring," travels incognito as a typically Delian, rhapsodic stream of consciousness but is actually a skillfully tailored set of variations, the theme of which-a majestically swaggering outburst of British chauvinism-unfurls itself only at the end.

Charles Groves, conducting the same orchestra that made the previous recording of the North Country Sketches, under Beecham (now on Odyssey Y 33283, with Appalachia), provides a meaningful alternative to that two-dozen-year-old classic. The differences in approach are threefold: Groves maintains great metrical constancy rather than Sir Thomas' more flamboyant rubato; Sir Charles builds climaxes sparingly while Beecham allowed a headier dynamic range; and the engineers or performers on the new recording have balanced choirs more evenhandedly, in contrast to the prevalent upper-voice leading of their predecessors, thus laying bare more of the harmonic values. I find both ways effective and suited to the piece.

The second side of this Angel issue offers two scores for which there is no competition from Beecham. Though Sir Thomas never recorded A Song of Summer, Barbirolli did-twice (most recently in a Delius Bax-Ireland collection on Angel S 36415). Groves's gentle, carefully sustained molding of the idyllic still-life scene is, however, as perfect a rendition as I could care to imagine.

For some reason, nobody has ever before recorded the 1912 Life's Dance--even though most books and articles on Delius mention it as an important composition and one that he twice revised before being finally content. The original title was The Dance Goes On, and the work has a whirling and obsessive propulsiveness (mixed ...

Charles Groves A major addition to Delius discography

... with more reflective interludes) that will remind some of the Liszt Mephisto Waltz, except that Delius' music always has an inner intensity I rarely find in Liszt. The orchestration is bold and incisive, and Sir Charles and the RPO have a fine time with it.

This major addition to the Delius discography is well recorded and pressed. The jacket features excellent notes by Eric Fenby (who else?) and a beguiling color photo of the Yorkshire countryside. If I can't go there in fact, at least Delius' music takes me there in spirit. A.C.

In quad: This is the kind of sound one has grown used to in basic quadriphonics. Instruments are well defined at the front, and there's lots and lots of hall ambience at the back. If any music thrives on such lush, sensuous sound, it is that of Delius. Delightful. R.L.

DVORAK Symphonies: No. 7, in D minor, Op. 70; No. 9, in E minor, Op. 95 ( From the New World), Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Václav Neumann, cond. VANGUARD/SUPRAPHON SU 7* and SU 8 1 ', $3.98 each.

Supraphon's new cycle of the Dvorak symphonies under the admirable direction of Vsiclav Neumann has appeared in its entirety abroad; now Nos. 7 and 9 join No. 8 (SU 2, February 1974 and May 1975) in the domestic catalog.

No. 7 gets a particularly impressive reading, which combines the brooding light and shade of the "traditional" approach (e.g., Talich's 78s and Sejna's early LP) with the taut discipline and precision of interpretations like Szell's (in Columbia D3S 814) and Rowicki's (Philips 6500 287). Neumann secures clear, precise execution and a great deal of balanced clarity--no small feat in this thickly scored work. But for all the punctiliousness (especially welcome is the straightforward phrasing of the last movement's second theme, which so many conductors heave and haul with lavish rubato) the over-all impression is one of rustic geniality. The wind playing is particularly poetic and memorable.

The New World follows a similar path but doesn't generate sufficient vitality on the one hand or burnished lyricism on the other. Again the lines are smooth and long, the orchestral playing both precise and tonally attractive, yet somehow I miss the exciting crack of the whip almost from the outset-for instance, in the introduction's low-strings-and-percussion answering motif. Nor is the famous Largo as eloquently rendered as in the wayward but very special Kubelik / Berlin performance (DG 2530 415). For the record, Neumann does not take the first- movement repeat, which does not bother me.

As usual with Supraphon's best orchestral work, the engineering is long on ambience without sacrificing detail; all the instruments sing out with just enough air around the choirs. Vanguard's pressings are altogether smoother than the Czech original of No. 8 (the only one of these I have heard), and Lois Gertsman's balanced, succinct notes unearth some interesting detiails concerning Dvorák's appointment at New York's National Conservatory of Music. I hadn't known, for example, that it charged only what students could pay and provided many scholarships to blacks. H.G.

Hamm: Chandos Anthems: No. 2, In the Lord put I my trust: No. 5, I will magnify Thee. Caroline Friend, soprano: Philip Lang ridge, tenor; King's College Choir, Cam bridge; Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, David Willcocks, cond. [Chris HazeII, prod.] ARGO ZRG 766, $6.98.

Though some writers, especially the Germans, consider Handel's Cljandos Anthems an Anglicized version of the German cantata style that Zachow taught to his young pupil in Halle, they are anything but the Lutheran cantor's art. In fact, these works, undoubtedly influenced by some of Blow's and Purcell's anthems, represent a unique, thoroughly English species of church music, dynastic and ceremonial, here pastoral, there dramatic, but without the profound Christian commitment we associate with Bach's cantatas. The Established Church was at this period a worldly, political organization, and the eighteenth century Englishman was partial to the Old Testament, because he regarded the English as another chosen people, with the Lord in variably and victoriously on their side.

The Chandos Anthems express this spirit to perfection and are firmly part of the English tradition, for which reason they are little understood and appreciated else where, even in the other English-speaking countries. It follows that the comparisons with Bach must be severely limited, for both the spirit and the techniques employed are worlds apart. These anthems are somewhat uneven, a number of the arias not quite reaching the high level of the choruses, and at times there is a dutiful but not very exciting choral fugue, but all of them contain great music, and some, like the eighth anthem, belong to the glories of the literature. And, of course, it was in these compositions that Handel laid the foundation for the grandeur of the choral style bet ter known from the oratorios.

The texts of the anthems recorded here, Nos. 2 and 5, are culled from several psalms.

Handel was no mean Biblical student and usually selected his passages from the Bible or the Book of Common Prayer himself. But the selections were made on a dramatic, not a theological, basis; Handel wanted contrast and a variety susceptible to musical exploitation.

Both works have borrowed music, mainly from Handel's earlier--or later--music; at times it is difficult to ascertain which version comes first. But it does not matter; Handel's transplanting technique is phenomenal. When he borrows anything, from a cadence to a whole piece, from his own or from another composer's music, the transplant as a rule appears natural and particularly suitable to its new surroundings.

Nineteenth-century historians and critics were terribly embarrassed by what they considered plagiarism on the part of England's national musical hero, some angrily declaring that a theft is a theft whatever the name applied to it. They did not yet know that the sainted Bach borrowed just as much as Handel-or any other baroque composer. After all, both Handel and Bach (who, by the way, purloined a bit from the sixth Chandos Anthem for his St. Matthew Passion) could compose "new" music at the drop of a hat; but, in accordance with baroque musical aesthetics, if some existing music was just right for the occasion, they made use of it no matter where it came from.

This recording is disappointing. A pall of emotional restraint, almost neutrality, hangs over what should be healthy, warm, and extroverted music. Everything is done diligently and conscientiously; why, the performers even sing Handel's misspellings rather than make the obvious changes (but the text is printed correctly!). Willcocks also retains the aria "Happy are the people," which scarcely belongs in the fifth anthem; it is markedly inferior to the rest, and there are no reliable sources for it. The boy trebles, though good, are by nature colorless, and they cannot muster enough volume when singing in low positions; when ever this happens there is imbalance in the choral sound. The pace and the dynamics are monotonous. There is no excitement and little drama, only a performance that is correct and competent (words whose import in critical vocabulary differs from their meaning in ordinary parlance). Of the soloists, tenor Philip Larigridge is a valiant singer, but his voice has a limited sensuous appeal; these arias are Italianate and require bel canto warmth. The soprano, Caroline Friend, is timid and wobbles a little; even a gentle aria calls for a round and colorful voice, and she shows little individuality. The orchestra is good, and the sound better than average.

All concerned, beginning with the conductor, misread the tone and quality of this marvelous music, which is quite surprising coming from an all-English ensemble. They usually know from long-embedded tradition that, unlike the German Lutheran, who beseeches the Lord, the Anglican informs Him of the situation, asking for ratification.

And no one embodied this confident and proud spirit more convincingly than the naturalized Briton from Halle. P.H.L.

Honegger: Symphonies: No. 1; No 4 Deliciae basiliensls). Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Serge Baudo, cond. [Eduard Her zog, prod.] SUPRAPHON 110 1536, $6.98.

Comparison--Symphony No. 1: Tabachnik/Orch. National Inédits ORTF 995 042

Comparisons--Symphony No. 4: Munch / Oral. National Mus. Her. MHS 981 Ansermeti Suisse Romande Lon. CS 8816 Although the Swiss-born Honegger had much stronger ties to the Germanic tradition than did his cronies of Les Six, he did not begin his First Symphony until 1929 (his first catalogued work dates from 1910). Commissioned by Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony and completed in 1930. Honegger's first effort at " absolute music" for full orchestra has been overshadowed by his four later symphonies; its premiere recordings appeared only recently.

True, the First Symphony lacks the expressive depth of its successors. And its musical language hardly makes for "easy" listening. Particularly in the first movement, Honegger applied to a wholly abstract context the "futuristic" writing familiar from Pacific 231 (1923): the marcato rhythms, harsh dissonances, marked instrumental contrasts, and thick-textured contrapuntal writing (including, in the middle of the first movement, a fugue hidden amidst other goings-on). But any deficiencies are largely offset by the pure energy of the first and third movements, the rhythmic and instrumental inventiveness and the wistful lyricism of the second, and the occasionally jazzy exuberance of the fourth.

The Fourth Symphony, one of Honegger's most warmly lyrical creations, contrasts strikingly not only with the First, but with the bleakly pessimistic Second (1941) and Third (1945-46) as well. Inspired by the "delights of Basel" and dedicated to Paul Sacher and the Basel Chamber Orchestra, the Fourth moves between a feeling of calm, pastoral nostalgia and a folk- inspired jocularity that can be heard especially in the third movement. The orchestral ambience is also much more placid and chamber-like than that of the First, though individual instruments like the piano are used to good effect.

This Supraphon disc belatedly completes Baudo's traversal of the Honegger symphonies. (Nos. 2,3, and 5, along with Pasto rale d'été, Chant de joie, and Pacific 231, were released domestically some years back on two Crossroads discs. All three discs have been boxed in a German set, Eurodisc/Supraphon 87 601 XK.) In both works, Baudo gives very good performances that do not quite measure up to the competition. Tabachnik's First Symphony for Inédits ORTF features fuller, deeper re corded sound and a better orchestra with a larger string section, a vital element in all of Honegger's orchestral works. Furthermore, the Tabachnik disc offers the only recordings of the marvelously dynamic "mimed symphony" Horace victorieux (1920-21) and the rarely heard Mouvement symphonique No. 3. In fact, though, neither recording of the First does the work full justice; especially in the final two movements, my standard remains a concert performance by Munch and the Boston Symphony.

Munch did record the Fourth, and his ac count, with the indispensable Dutilleux Cinq Métaboles, is one of the gems of the Musical Heritage Society catalogue. Ansermet's Fourth has the best sound, and its coupling is a searing performance of the Third Sym phony. The Supraphon disc, however, per forms an invaluable service by providing relatively convenient access to the First Symphony, in a quite satisfying interpretation. Unfortunately the Czech-pressed disc serves the efforts of Baudo and the Czech Philharmonic markedly less well than the German-pressed set noted above. R.S.B.

KORNGOLD: Die tote Stadt, Op. 12.

Marietta. Marie Carol Neblett (s). Juliette Gabriele Fuchs (s). Lucienne Patricia Clark (s). Brigita Rose Wagemann (ms). Paul Rene Kollo (I) Gaston; Victorin Anton de Redder (t). Count Albert Willi Brokmeier (1). Frank Benjamin Luxon ( b). Fritz Hermann Prey ( b). Talz Boys' Choir; Bavarian Radio Chorus and Orchestra, Erich Leinsdorf, cond. [Charles Gerhardt, prod.]

RCA RED SEAL ARL 3-1199, $20.98 (three discs, automatic sequence). Quadriphonic: ARD 3-1199, $23.98 (three Clued radiscs).

As a great fan of Erich Wolfgang Korngold's film music, as well as what concert music I have heard (including the violin concerto and the powerfully dramatic symphony), I must confess to great disappointment in his first large-scale opera Die tote Stadt (The Dead City), completed in 1920 when he was twenty-three. Not that the music is all that bad, although little of it has the appeal of many of the composer's other works, but it is by and large bad music drama.

Based on Bruges la Morte by the nineteenth-century Belgian symbolist Georges Rodenbach, the libretto concerns itself, in classic symbolist fashion, with death and absence, here in the form of an obsession with a dead woman and her reincarnation in an earthly double. Typically-and essentially, for the metaphysics involved-the tale ends in the triumph of the non-flesh, of non-presence, of death.

Yet this " reworking" of Bruges la Morte represents a classic case of pre-Hollywood Pollyanna-ism. By using the gimmick of putting the " negative" part of the story into a dream, the libretto is able to justify the final conversion of the hero to the forces of life. Christopher Palmer, in his long apologia in RCA's extensive booklet, states that the librettists were trying to avoid the "exclusivity," whatever that means, of the symbolist aesthetic (which is hardly " exclusive" to France). But either you work within the limits of a certain domain envisaged by an author or you turn to a different writer; by tacking a happy ending onto Rodenbach's lugubrious vision, and by applying a nicely Germanic, logical distinction between "real" life and dream to a work that assumes an ambiguity between the two, the libretto very simply emasculates the work's narrative as well as its thematic impact.

Unfortunately, the operatic style seconds almost every step of the way the librettists' non-conception of the story. Perhaps the tale does not need a Debussy (who knew and admired Rodenbach), although the possibility, suggested by Palmer, is intriguing.

Carol Neblett--A skillful, dynamic Marietta/Marie.

But I was constantly dumbfounded by how badly Korngold's swirling flourishes and fortissimo emphases capture the mood indicated by the stage directions or even by the words that are being sung. Indeed, Korngold time and again has his singers pompously declaiming lines that seem to call for startled understatement, his orchestra thumping away with histrionic punctuation where one would want a misterioso feeling.

It is all rather like Richard Strauss man qué (notwithstanding producer Charles Gerhardt's protestations to the contrary in the booklet), with all the Straussian gran diloquence but none of the mood (and I am not one of Strauss's greatest fans). Perhaps the greatest problem is the writing for the main character, Paul, who carries at least 60% of the burden. Korngold's strategy for communicating the torment of an obsessed, death-oriented soul is a series of exclamations at roughly the volume level of a New York subway. Perhaps I am overreacting to René Kollo's grating performance-color less, strained, wobbly, and, to make matters worse, too closely miked. But surely some of Kollo's difficulties relate to the writing itself, both verbal and musical.

The other singers and the orchestra make an excellent impression. Soprano Carol Neblett's diction may not be perfect, but I would rather hear her rich, fluid voice singing nonsense syllables than hear Kollo bleating perfect German. Beyond the ingratiating ease of Neblett's vocalism, there is a skillful and dramatic use of dynamic and timbral contrast, the voice subtly changing hue as it moves from range to range. Fortunately Marietta/Marie has much of the op era's best vocal writing, including the Act I "Lute Song." It is, however, the orchestra that proves the opera's most interesting character-not in a dramatic way, but in the manner of a talented acrobat performing skillful, even graceful, feats above the stage to distract the audience from a boring melodrama. Although here and there I note a certain stodginess characteristic of Leinsdorf performances, in general he elicits crisp and sonorous playing from the orchestra, and most of the opera's best moments (concentrated in Act H) belong to the instrumentalists. With respect to orchestral idiom, though in no other respect, I can agree with Gerhardt that Korngold's thoroughly original style has nothing to do with Strauss's (or, for that matter, with Puccini's, another often suggested influence). As producer of this recording, Gerhardt is the nearest thing it has to a hero (despite the overmiking of Kollo). The orchestral playing is reproduced with that special lus ter familiar from the recordings he and his frequent collaborator George Korngold have made for RCA. At least the most at tractive aspects of Die tote Stadt have been done full justice. R. S. B. Lim: Hungarian Rhapsodies (5). Claudio Arrau, piano.

DESMAR DSM 1003, $6.98 (mono) [from COLUMBIA originals recorded 1951-52, previously unreleased]. No. 8, in F sharp minor; No. 9, in E flat; No. 10, In NO. 11. In A minor; No. 13, in A minor.

One of the most inspired repertory adventures of the brand-new Desmar company was obtaining from the International Piano Archives the rights to issue for the first time these recordings, made in 1951-52 for Columbia but inexplicably never released by that company.

If you're already an Arrau fan, you'll re member that he studied with one of Liszt's own last pupils, Martin Krause, that he first won the prestigious Liszt prize at the age of only sixteen, and that at least three of his current Philips releases are devoted to Liszt originals (802 906 and 6500 043) and transcriptions (6500 368). A hasty check of his earlier discography doesn't turn up any other Hungarian Rhapsodies, which enhances the value of the five present examples. They become well-nigh invaluable, however, for both the gusto and the magis terial bravura with which the Arrau of nearly twenty-five years ago endows these pianistic showpieces. And, what is far more unexpected, the recording itself not only does full justice to Arrau's robustly ringing tonal qualities, but also achieves (despite its rather dry acoustical ambience) a truly remarkable presence.

If there are more such gems as this in the International Piano Archives, Desmar (or IPA itself) can do keyboard connoisseurs an incalculable service by prying them from the vault. R.D.D.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 5, in C sharp minor; Kindertotenlieder. Christa Ludwig, mezzo-soprano*; Berlin Philharmonic Or chestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Hans Hirsch and Hans Weber, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2707 081, $ 15.96 (two discs, manual sequence). Comparisons-symphony: Solti/Chicago Sym. Lon. CSA 2228 Walter/N.Y. Phil. Odys. 32 26 0016 Bernstein/N.Y. Phil. Col. M2S 698 Haitink/Concertgebouw Phi. 6700 048.

Comparisons--Kindertotenlieder: Ludwig, Vandernoot/Philharmonia Sera, S 60026 Baker, Bernstein/Israel Phil. Col. M33532 Ferrier, Walter/Vienna Phil. Odys. 32 26 0016 or Sera. 60203 Prey, Haitink/Concertgebouw Phi. 6500 100.

The belated Karajan-Mahler matchup (this is likely the beginning of an eventual cycle; due shortly is Das Lied with Ludwig and Kollo, with the Rückert-Lieder on Side 4) is an incongruous one. Could any conductor be more removed-stylistically and temperamentally-from the world of the Bohemian Jew and his barbed ironies? This Fifth does" sound like an external conception, rather than one evolved through long and intimate involvement with the music and its ambience. The reading is often fanatically literal-minded, yet without apparent comprehension of the composer's intent. The ending of the first movement is marked with a progressive diminuendo; the final ppp stroke of the bass drum is virtually inaudible. Conversely, when the Adagietto reaches fff, the Berlin strings scream wildly. The marking "some what more restfully" for the trio-like section of the Scherzo brings violin playing that is oily and effete. Tempo relationships are exaggerated, notably in the Scherchen-like contrast of the three basic pulses of the opening funeral march. Mahler's piano roll of this movement (and Solti's set, among modern recordings) attests that the point can be made more discreetly.

There is much, too, that Karajan misses altogether in this performance. In the second movement, tempo indications from No. 13 through the end are ignored or distorted, so that the basic structure is pulled out of recognizable shape. (It is, though, a series of grand and hyperbolic dramatic gestures.) Karajan fails to join the Adagietto and finale, as indicated by the score's attacca, and in the finale he falls into the frequent trap of anticipating by several pages the pesante slowdown actually called for six bars after No. 33: The instrument used in the Scherzo sounds like no woodblock I've ever heard, but something more metallic. There are also minor blemishes in playing and balance.

In fairness, there are exciting and intense things in Karajan's Fifth including much brilliant playing, and no recording is perfect. (There is indeed such interpretive latitude in the piece that over-all timings range from Karajan's 74 minutes to Abravanel's 61.) Yet Solti's has for me the most legitimate and vivid drama and virtuosity, along with spectacular engineering. Both New York performances, Walter's and Bernstein's, contain more humanity and warmth, with a genuinely Viennese lilt in the Scherzo. Haitink best explicates the contrapuntal rigors and orchestral shading of this most " absolute" of Mahler's scores.

Christa Ludwig's earlier Kind ertotenlieder is still available and at the Seraphim price easily constitutes the best coupling by a female singer of this and the Wayfarer Songs. Still admirable are the warmth and urgency, the superb projection of the text, and the driving and haunted intensity of the rapidly moving final song (" In diesem Wetter"). But time has taken some of the bloom from her vocal equipment: some hardening of the tone, a biting off of consonants at phrase ends, a shade less finely spun legato. For many, DC's more transparent and open sonics will compensate, and Karajan steers the ship more confidently than Ludwig's earlier conductor, Vandernoot. On the other hand, some of the Berliners' playing strikes me as less idiomatic than the Philharmonia's--the oboes, for example.

There is a rich choice of first-rate recordings of this intimate and heartbreaking cycle. The recent Baker/Bernstein (October 1975) is a grand, flowing, darkly passionate performance, but both Ludwig and Baker must still be judged by the standard of Kathleen Ferrier, whose eloquent presentation of this music with Walter and the Vienna Philharmonic is available on Odyssey as the filler for Walter's Fifth Sym phony and on Seraphim in a Ferrier miscellany (to mention only current domestic issues). One copy may be enough, but don't settle for less than that! Still, I would suggest that one's first Kindertotenlieder should be a man's recording; the cycle is about a father's grief, and both poet and composer were fathers. As I find both of Fischer-Dieskau's recordings too calculated and self-admiring, my choice would be Prey/Haitink, for the simple and unpretentious clarity and ease of the singing, the ideal pacing, the plangently expressive first-desk work of the Concertgebouw, and the technical splendor of the recording.

A.C. MEYER Issis: Songs. Dietrich Fischer Dieskau, baritone; Karl Engel, piano. [Andreas Holschneider and Cord Garben, prod.] ARCHIV 2533 295, $7.98.

Menschenfeindlich; ich das Liedchen klIngen; Die Rose. die Lilie, die Taube, die Sonne; Komm; Der Garten des Herzens; Sie und ich; Sicilienne, Standchen. Due Rosenblatter; Le Chant du dimanche; Le Poète mourant, Cantique du Trappiste; Scirocco; Mina Our long-standing gratitude to Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau for his unceasing efforts to enlarge the boundaries of song literature falters in the face of the present record.

Meyerbeer's songs prove banal in the extreme, and Fischer-Dieskau's performances seem calculated to underline their weak nesses.

All fourteen titles come from the collection of Forty Songs ( French and German), published in Paris in 1849, and fall into two categories: lyric pieces (a sicilienne, a serenade, a gondolier's ditty, and various nature pieces, including settings of Heine's "Mr' ich das Liedchen klingen" and " Die Rose, die Lije") and more dramatic effusions, like the long " Cantique du Trappiste" and the even longer-indeed, endless seeming--"Le Poète mourant," which is really a pictorial scena. All are essentially strophic in form, even " Le Poète mourant," which makes use of a contrastingly freer introduction and conclusion. To the danger of boredom inherent in melodic repetition Meyerbeer was by no means deaf. To accommodate changes in mood and verbal sense he is quick to vary both the vocal line and the piano accompaniment, and in search of dramatic expressivity he is not afraid to employ some surprisingly bold modulations.

These songs, in other words, are by no means the products of an insensitive hack.

Meyerbeer was indeed a hack, but an acutely sensitive one. He meant well enough, but he simply lacked the requisite inspiration. One hardly needs to invoke the genius of Schumann in the case of the two Heine poems referred to above to realize how vapid and contrived Meyerbeer's lyric talents were. His lack of melodic inspira tion is immediately and equally apparent from such pieces as the quick and playful "Scirocco" and the lugubriously sanctimonious "Le Chant du dimanche."

Fischer-Dieskau takes up the composer's cause as if performing a painful duty. All the recent mannerisms that have proved so disconcerting to his old admirers are present here: violent dynamic shifts, sudden bursts of vehemence, the arbitrary emphasis of a single word, long stretches of singing under the note. New to my ears and equally unbearable is Fischer-Dieskau's tendency in legato singing to omit trouble some consonants and to swallow unaccented syllables.

Karl Engel plays well, though the recording unduly minimizes his share in these proceedings.

Disconcertingly enough, the texts-all given in English, French, and German-are printed in an order different from that in which they are sung. In the two cases where Meyerbeer used French versions of German poems Archiv offers English translations of the German originals rather than trans lations of what the composer actually set, though the differences, especially in the case of " Le Chant du dimanche," are con siderable. D.S.H.

Mozart: Piano Works. Michael Cave, piano forte. ORION ORS 75185, $6.98.

Adagio in B minor, K. 540. Sonatas: in D. K 311; in B flat, K. 333. Variations on Paisiello's " Salve tu, Domine," K. 398.

The period pianoforte in these performances has a mellow, resonant sound below and the characteristic harpsichord-like twang in the higher reaches. Michael Cave's performances are facile and musicianly, achieving most admirable results in the impassioned B minor Adagio. Sometimes, especially in the development section of K. 333's slow movement, he bears down rather heavily and squarely on the writing, possibly to suit the instrument.

For both playing and listening to this music, I much prefer a conventional concert grand. For starters, try Gieseking (Seraphim) or Kraus (Odyssey).1-1.G. Mutter Thamos, Konig in Aegypten (incidental music), K. 345 (with Symphony No. 26, in E flat, K. 184). Karin Eickstaedt, soprano; Gisela Pohl, alto; Eberhard Büchner, tenor; Theo Adam and Hermann Christian Polster, basses; Berlin Radio Chorus; Staatskapelle Berlin, Bernhard Klee, cond. PHILIPS 6500 840, $7.98.

Thamos, King of Egypt was Mozart's first excursion into the field of incidental music.

In such a work, popular in Germany in the latter part of the eighteenth century and the first of the nineteenth, the overture pre pares the audience for the drama to follow, the other instrumental pieces are descriptive of mood and action, and the choruses add their comments and summarize the moral lessons; there is very little solo singing. Thamos does not have an overture, but Mozart sanctioned the use of his K. 184 symphony for this purpose. The first version of the incidental music dates from 1773, but what is recorded here is the second, of 1779, an immense improvement, in which Mozart added what turned out to be the finest piece, the concluding chorus.

Baron Gebler, the author of the play, was e a high-ranking civil servant who dabbled in letters. His play is atrocious, but one aspect of it commands our attention: It has Masonic ramifications that appealed to Mozart, and there is an unmistakable kinship to The Magic Flute in this music. Since it is most unlikely-indeed impossible-that this miserable play will ever be revived, how can we rescue the great music Mozart associated with it? This recording, a coproduction of Philips and East Germany's Deutsche Schallplatten, does the right thing in giving us the complete score, but I am thinking of concert performances enabling the public to enjoy music that Mozart himself regarded highly.

Of the five orchestral interludes, the third, in G minor, and especially the fifth, in an agitated D minor, are good pieces that pre figure the music of the Queen of the Night. The others, taken out of context, are of modest interest and probably expendable.

It is quite another matter when we come to the choruses. The first of these, a hymn to the rising sun, is an attractive composition in sonata rondo form, in which little duets serve as episodes. The latter somewhat diminish the value of the piece, but it remains thoroughly viable. The second chorus (No. 8 in the score) is one of the best choral pieces in Mozart's canon, and the final chorus (No. 7b) is simply tremendous. It opens with a bass solo that immediately re calls the Commendatore in the final scene of Don Giovanni; it is stunningly dramatic and very well sung by Theo Adam. This is really a large-scale operatic finale that could grace any of Mozart's great operas.

The jubilant end once more points to the joyous close of The Magic Flute. It seems to me that the two good entr'acte symphonies and the three choruses would be eminently suitable for concert performance.

Mozart uses a rich orchestra including three trombones, which do not play colla parte but have a powerfully dramatic role.

The elaborate orchestral accompaniment is beautifully coordinated with the choral set ting; the faithful musical declamation of the text is nowhere disturbed. The Philips soloists are good, the orchestra mobile and accurate, and the chorus first-class. The conductor, Bernhard Klee, must be a good operatic hand: He does not miss the dramatic implications and has a good sense for a flexible tempo. The sound is excellent. P.H.L.

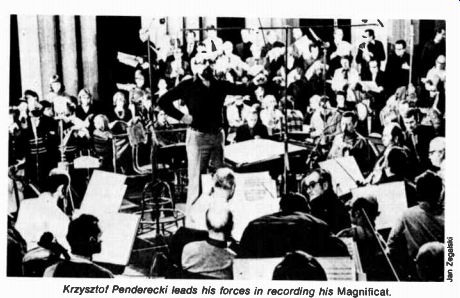

PENDERECKI: Magnificat. Peter Lagger, bass; soloists and boys' choir of the Cracow Philharmonic Chorus; Polish Radio Chorus, Cracow; Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Krzysztof Penderecki, cond. ANGEL S 37141, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

Few composers today are writing religious music as deeply moving and radiant in spirit as Penderecki.

In his Magnificat (1973-74), he praises God in the manner of one who lives in dark ness; it is a glorification that rises de pro fundis, from the depths, as the chorus, tentatively, with more hope than joy, sends its words heavenward. The technique is distinctively that of this composer, but in this music he has become more conservative and traditional. Older forms such as passacaglia and fugue are employed; meters are

-------- Krzysztof Penderecki leads his forces in recording

his Magnificat.

comparatively simple and regular, yet the writing for choruses, soloist, and orchestra is clearly in the Penderecki style, a style that is (obviously) fully grasped by Penderecki the composer but (less obviously) also fully realized by the composer as conductor.

The atmosphere of the recording is one of great spaciousness, and I found that SQ de coding and four speakers enhanced this effect. A recording as fine as this should stimulate concert performances of the Magnificat. This is important religious mu sic, rising from the matrix of our own times, and it is something we must hear to under stand our world and ourselves. R.C.M.

Pitokortzv: Symphony No. 5 in B flat, Op. 100. London Symphony Orchestra, André Previn, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.]

ANGEL S 37100, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

Comparisons: Bernstein/ N.Y. Phil Col. MS 7005 Ansermet/ Suisse Romande Lon. C56406 Martinon/ Paris Conservatory St. Tr. STS 15195

The Fifth is the most popular of Prokofiev's "contemporary"-style symphonies (in other words, excluding the Classical) and arguably the greatest. In presenting his view of it against the heavy recorded com petition, André Previn scores a qualified but respectable success.

My reservations are primarily structural.

Though the opening Andante can by itself thrive on Previn's spacious handling, and the Adagio third movement on the kind of swift pacing heard here, the combination in one performance tends to shift the center of gravity. Within the first movement, more over, each return to tempo primo should restate a basic pulse, but this reading doesn't quite gauge that precisely enough- what is heard at No. 8 of the MCA score seems faster than what comes at No. 23.

The sinister brass ostinato starting at No. 48 in the scherzo, though marked l'istesso tempo, is taken with the rather popular grotesque deliberation of so many conductors.

In the slow movement, the string tone at No. 59 is tentative rather than lushly passionate, which may result from faulty rhythmic control (two-against-three be tween first and second violins).

So much for reservations. On the credit side, the over-all phrasing of the work has a flow and dignity that emphasize its serenity rather than its frenetic motor energy. ( Prokofiev regarded this as a " symphony about the spirit of man.") Thus, attacks may not have the bite and fierceness found in other performances, but there is no want of polished nuance, of careful attention to expressive meaning and to the blends of timbre among winds, low strings, and the obbligato piano.

The humaneness and restraint of Prenin's approach and the fine sound will undoubtedly win many adherents for this edition. Those seeking something more heatedly emotional are directed to Bern stein's sweeping treatment: enormous in scale, seething with drama, and also quite rich in texture. I lean especially to Ansermet's wryly pointillistic and swaggering interpretation, which is very vividly recorded. For the budget-conscious, Martinon's taut and febrile first recording (now on Stereo Treasury) is recommend able, at least until Odyssey reissues the Szell. Of the others, Sargent (Everest) and Ormandy ( Odyssey) are passable; Oistrakh (Melodiya/Angel), Horenstein (Vox), and Karajan (DG) forgettable. The Fifths of both Prokofiev symphony cyclists, Marti non (Vox) and Rozhdestvensky (Melo diya/Angel), are compromised by raucous playing and recording. A.C.

rÉ -31 Ptiacati: The Fairy Queen. Honor Sheppard, Jean Knibbs, and Christina Clarke, sopranos; Alfred Deller and Mark Deller, countertenors; John Buttrey and Neil Jenkins, tenors; Maurice Bevan and Norman Platt, baritones; Stour Music Festival Chorus and Orchestra, Alfred Deller, cond.

VANGUARD EVERYMAN SRV 311 / 2 SD, $7.96 (two discs, automatic sequence).

Comparison: Britten/English Chamber Orch. Lon. OSA 1290

Unlike Benjamin Britten's recent recording of Purcell's Fairy Queen (July 1973), for which the score was edited with great skill and taste, this version by Alfred Deller and his Stour Music Festival forces (recorded by Harmonia Mundi) follows the original manuscript of 1692, thus providing an inev itable and instructive comparison.

The original manuscript is incomplete, most of it not in Purcell's hand and patently a hastily put-together affair. As I listened to Deller's recording, it became clear why Britten felt it necessary to edit the score.

While the "original" version still offers magnificent music, there are thin spots, in complete measures, and obviously sketchy orchestration. Notably, the continuo had to be supplied; its absence in Deller's version is particularly noticeable.

This recording has many admirable qualities. The chorus is superb and marvelously in tune, as is the orchestra (the recorders and trumpets especially are brilliant), and the sound is first-class. The singers are good, and their airs are attractively sung.

Unfortunately there are flaws, chief among them a somewhat enforced daintiness that hurts the music. And while the solo ensembles are remarkably well done when the tempo is slow or moderate, they become a bit chaotic when fast coloraturas or par landos are sung with that come-come-trip it-trip-it buoyancy. The tempo in such ensembles should always be governed by the ability of the singers to maintain clarity of enunciation and part-writing, something that Britten always does. I also have some reservations concerning such naturalistic effects as the tongue-tied singing of the ine briated Poet; without visual support, the device of off-key singing can be merely irri tating.

In sum, this is a commendable and gener ally very attractive presentation, but Brit ten's version seems to me preferable be cause of its uniformly controlled observance of the musical values and the absence of any period mannerisms. P.H.L.

RACHMANINOFF: Aleko.

Aleko The Old Gypsy Zernfira The Young Gypsy The Old Gypsy Woman Chorus of the Sofia TVIR Ensemble; Plovdiv Symphony Orchestra, Rouslan Raychev, cond. MONITOR HS 90102/3, $7.96 (two discs, automatic sequence). Nicola Ghiuselev (bs)

Canal& Pellfov (bs)

Blagovesta Karnobatlova (s)

Pavel Kourshoumov (1)

Tony Christova (a)

Aside from an aborted setting of Maeterlinck's Monna Vanna ( don't confuse it with Février's completed, and once voguish, piece on the same subject), Rachmaninoff's operatic output is restricted to three one-act works. Of these, Aleko is the best-known by name, for the simple reason that its baritone cavatina once received an eloquent recording by Chaliapin, and has been turned to ever since by low-voiced Slays in search of some un-hackneyed lyric heartbreak. It is also tho first of the com poser's operas to receive more than a single complete recording. (The Covetous Knight is currently available on Melodiya /Angel SRBL 4121; Francesca da Rimini has yet to he recorded.) Aleko is a student work, dating from Rachmaninoff's twentieth year. It sounds it, too, though in saying this I don't mean to dismiss it. The score contains a number of nice melodic ideas and a firm, if conventional, grasp of vocal and instrumental effect. It is laid out in a traditional series of closed-form numbers, and the ones that carry the expressive burden-the payoff numbers-find the composer responding with a modest but real inspiration.

The weakness lies in the tougher compositional challenge of actually " making" the score-providing solutions of reasonable interest for all the moments that are not lyrically or dramatically obvious, creating developments and transitions that have some leading force. And in these respects the work is altogether too predictable. It sounds as if Rachmaninoff had his heart in the bigger moments but didn't get his head sufficiently into the rest.

The opera is drawn from a Pushkin poem called The Gypsies. These Bohemians are, as we might expect, romanticized figments whose overriding concern in life is avoidance of any means for regulating the rebellious sexuality of their women. Each generation, the work seems to say, sees the same pattern of faithlessness repeated, and each responds by saying, "Well, there you are, what can you do ...?" Aleko himself, presumably because he was raised among the uptight settled folk, does not share quite so resigned an attitude with respect to his young wife Zemfira and, in fact, finishes off both her and her lover. It is a sort of Tabarro of the steppes, if we allow for the melancholy irony of Aleko's final condition: Having fled the constraints of lawful society, he finds himself acting out the role of vengeful enforcer and now is truly alone on the lone prai-ree. Though the libretto is by none other than Nemirovich-Danchenko, very highly regarded as a director and teacher, it is rather like the score-conventionally effective and unambitious, con tent with setting forth situation and incident without much care or sense to the psychology behind them.

The new recording does not make the most powerful imaginable case for Aleko.

The orchestra makes a decent enough basic sound, but there is no real delicacy or sharpness in the playing, and, whenever rhythmic precision and unanimity are important, ensemble and conductor are in trouble. This music, with its secondhand Tchaikovsky and Rimsky-ized Borodin (particularly the Polovtsian Dances, heard distinctly in the opening chorus), and with much reliance on harps glissing through strings tremolando, needs all the nuance and care it can get, and this is only adequate.

Nicola Ghiuselev's voice sounds as darkly beautiful here as it does on the Bulgarian Khovanshchina recording. The tessitura hangs a trace high for him (the role does call for dramatic baritone, and Ghiuselev is a bass), but he manages with only one or two clumsy moments, and he brings a general kind of emotional vitality to the part without ever kindling much of an imaginative flame. The second bass part contains the most persuasive sustained passage apart from Aleko's cavatina-an other male complaint, involving Zemfira's mother. Dimiter Petkov sings its more subdued moments quite beautifully, the fuller ones with a kind of encirclement technique.

The Zemfira, Karnobatlova, does a solid, basic, sing-the-notes job with a ditto medium-weight soprano; the tenor Kourshoumov, who has a listenable lyric tenor with some of that Slavic alloy up top, spends too much of his time six or eight hertz below pitch.

The recording is reminiscent of some of the good early stereo work: full-bodied, full- ranged sound, with overly distinct channel separation. The packaging pro vides a quick synopsis, glosses of the more important passages, and a complete Russian libretto without translation or transliteration. I think it is legitimate to note that there is just an hour of music spread over the four sides; surely one side could have been devoted to another piece, or possibly some Ghiuselev bass arias. This is short measure, " budget" price or no.

The previous recording. now about twenty years old, should also have at least a discographic note. It was Concert Hall CHS 1309. Bolshoi under Golovanov, with Nina Pokrovskaya, Ivan Petrov, Alexander Og nivtsev, and Anatole Orfenov. Complete on a single disc, it was also a better performance from the conductor and all the male soloists. ( It is especially good to hear Ognivtsev as the Old Gypsy, sounding notice ably better than he has on more recent re leases.) Its sound, however, was far worse than Monitor's, and in any event it is unobtainable except perhaps in rarity shops. C.L.O.

SAINT-SAË NS: Orchestral Works, Vol. 1. Ruggiero Ricci, violin' ; Laszlo Varga, cello'; various orchestras. VOX OSVBX 5134, $10.98 (three QS-encoded discs, manual sequence). WorIcs for Violin and Orchestra': Concertos: No. 1. in A minor, Op. 20; No. 2, in C, Op. 58: No. 3, in B minor. Op.

61; Introduction and Rondo capriccios°, Op. 28; Havanaise, Op. 83 (with Luxemburg Radio Orchestra, Pierre Cao, cond.). Romance, Op. 48; Morceau de concert, Op.

62; Caprice andalou, Op. 122 (with Philharmonia, Reinhard Peters. cond.). Works for Cello and Orchestra': Concerto No. 1, in A minor, Op. 33; Allegro appassionato, Op. 43 (with Luxemburg Radio Orchestra, Louis de Froment, cond.). Concerto No. 2, in D minor. Op. 119 (with Westphalian Symphony Orchestra, Siegfried Landau, cond.). Comparison-cello works: Walevska, Inbal/Monte Carlo Phi. 6500 459 Since the Saint-Saëns cello works here (plus an inconsequential suite) have been anticipated by Walevska and Inbal for Philips (September 1975), it's in the violin and-orchestra domain that Vox's enterprise proves most valuable.

Ricci, long notable in this repertory, is an apt choice for soloist, and he naturally be gins by replacing his older versions of the familiar Third Concerto (for Vox in 1948), and Havanaise and Introduction and Rondo capriccioso ( for London in 1960). He goes on not only to replace his pioneering First Concerto (for Decca in 1965), but also to provide the first recording ever of the long-obscure Second Concerto, plus what well may be firsts (in this country at least) of three rarely heard shorter concerted pieces.

All the novelties prove to be markedly more effective than one would assume from the fact that they long have been almost completely unknown to nonspecialist listeners. The so-called Second Concerto, Op.

58, was actually the first, composed in 1858, some nine years before Op. 20, but inexplicably not performed in public until 1880. I say "inexplicably," because it proves to be a decidedly characteristic product of the composer's elegant craftsmanship. While it not unreasonably sounds a bit old-fashioned at times, it has genuine dramatic moments and, in particular, an excitingly joy ous windup guaranteed to bring the house down in concert performances. All three shorter pieces also are distinctive display cases for a bravura soloist like Ricci: a prodigally episodic Morceau de concert, a romantically rhapsodic Caprice andalou, and a lighter-weight but gracefully engaging Romance.

Unexpectedly though, the popular Third Concerto comes off less satisfactorily than any of the other violin works. Ricci himself permits his occasional moments of over intensity elsewhere to get out of hand here, while the orchestral playing, routine at best throughout the entire set (regardless of which organizations are involved), is at its roughest and most heavy-handed. But per haps a considerable part of the blame should be assigned to the engineers for this particular 1973 session. Most of the other recordings, made on various dates in 1974, sound better, although even they--at least when reproduced in stereo only-are rather lightweight sonically and over-dry in acoustical ambience. Quite possibly they may achieve fuller tonal body in quadriphonic playback.

The cello works are generally somewhat more successfully recorded, yet even in this respect they are surpassed by the greater warmth and richness of the competing Phil ips versions. And while it's good to hear Laszlo Varga (for some years principal cel list with the New York Philharmonic) given such ample stardom, his admirably skillful playing here seems relatively small-toned and lacking in personality projection in comparison with the more flamboyant but far more exciting Walevska performances.

What is perhaps most valuable is the added weight of Varga's testimony, so different from Walevska's yet carrying no less conviction, to the musical as well as display vehicle significance of the long- neglected Second Cello Concerto. With each rehearing I'm more impressed by it, finding it ever harder to understand why so effective a work hasn't yet achieved the concert hall triumphs it is so masterfully designed to win. R.D.D.

S HOSTAKOVICH: Symphony No. 5, Op. 47. Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, cond. [Jay David Saks, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1149, $6.98. Tape: » ARK 1-1149,

$7.95; .0J- ARS 1-1149, $7.95. Quadriphonie: ARD 1-1149 (Quadradisc), $7.98; ART 1 1149 (0-8 cartridge). $7.95.

Comparisons: Ormandy/Philadelphia Previn/London Sym M. Shostakovich / U.S.S.R. Sym.Col. MS 7279 RCA LSC 2886 MeL/Ang.SR 40163

There is something about the Shostakovich Fifth, surely the most played and recorded symphony of the past half-century, that renders it performer-proof; it never fails to have a stirring effect. Not that all performances are equal. For example, most conductors ( including the composer's son Maxim). in responding to the " natural" contours of the music, gloss over the fact that the tempo speedups in the first movement actually are marked later than one would assume from the character of the passages. And there is no textual sanction for opening the finale at the breakneck (if irresistible) speeds employed by Bernstein, Previn, Rodzinski, Silvestri, and others.

Ormandy's Columbia recording found him at his un-hysterical, dignified, and musicianly best, and the new version is if any thing even better. In many of his recent recordings-such as the Tchaikovsky Fourth (ARL 1-0665, July 1975) and the Rachmaninoff Second (ARL 1-1150, December 1975)-I have been alarmed by the phlegmatic and mannered qualities creeping into his typical straightforwardness, but here he achieves an almost Klemperer like massiveness and intensity. Ormandy/ RCA times out some three minutes longer than Ormandy/Columbia, and the extra breadth reflects a taut, craggy sense of concentration, a sustained inwardness and grandeur-all immensely affecting. Note, for example, in the first movement the finely graded adjustments at the poco stringendo ( No. 31), the largamente climax, and the return to the basic moderato pulse of the movement. The hairpins in the string bass introduction to the scherzo are neatly pointed, and the percussion details in the coda of the finale have never been so meticulously clear.

The playing of the Philadelphians is among the best they've clorie lately for discs. The recorded sound, in contrast to the dry, steely, gimmicked Rachmaninoff Second, has all the depth, smoothness, and bloom one could ask for.

The fine liner notes are by HF's regular Shostakovich reviewer, Royal S. Brown, which incidentally is why he isn't reviewing this record. That said, I must add that I can't second his July 1972 recommendation of the Maxim Shostakovich account, for I am more bothered by its occasional loose ness of discipline and the shrill and coarse sonics. Previn's RCA recording is sweeping and reckless but finer-grained and more effective over-all. He will doubtless surpass that decade-old effort when he gets around to an EMI remake, but even then the new Ormandy will offer severe competition. My personal favorite, though, is the Skrowaczewski/Minneapolis, whose lithe energy, structural insights, vital tension, and crisp and biting sonics are quite special indeed; I hope it returns soon as a Mercury Golden Import. A.C. In quad: At the opening of the first movement the canon between the violins (at the left front) and tho cellos and basses (at the right back) makes plain what sort of record ing this is to be: very quadriphonic. During much of the two movements on Side 1, I have the feeling that the orchestra is being picked apart before my very ears and isolated in well-defined compartments all about me. The remaining two movements fare much better, particularly in the pas sages for massed strings, and are in fact very exciting. But the over-all impression for most listeners will, I fear, be one of discreteness rather than discretion. R.L.H

SIBELIUS: Symphony No. 1, in E mi nor, Op. 39; Belshazzar's Feast, Op. 51'. Orchestra and London Symphony Orchestra, Robert Kajanus, cond.

TURNABOUT THS 65045, $3.98 (mono) [from English COLUMBIA and HMV originals, recorded 1930 and 19321.

The Finnish conductor Robert Kajanus was reportedly his great compatriot's favorite interpreter of his music, and he recorded much Sibelius for English Columbia and HMV in the early electrical era. All of those recordings have been reissued in England in World Records' pair of "Great Sibelius Interpreters" sets (SH 173/4 and SH 191/2), from which this Turnabout Historical Series disc is drawn.

In the 1970s. the anonymous English orchestra heard in Kajanus' First Symphony sounds ragged and under-rehearsed. Motifs passed from one instrumental line to an other cannot be followed clearly in the fog of casual articulation and balance. The tubby and constricted recording is no help either. Tho performance itself is characterized by a constantly undulating, "old-fashioned" rubato, which doesn't help convey a clear idea of the symphony's structure.

However, the reading does generate a sense of grand passion and spontaneous excitement and conviction. Often the instrumental sounds are impressive, with full and singing cellos and bold and snarling brasses. Worth hearing certainly, but as an over-all statement of the score no challenge to such modern accounts as those of Barbirolli (Angel S 36489) and Bernstein (Colum bia M 30232). Kajanus' reputation is better served in the lightweight but atmospheric Belshaz zar's Feast incidental music, which benefits greatly from two years of recording progress and the presence of a real orchestra, the London Symphony. The con amore string playing in the second section and the plangent oboe finale are old and dear friends to anyone who has grown up with the shellac originals.

I do hope that Turnabout will give us more of Kajanus' best Sibelius, notably the Third and Fifth Symphonies and the most powerful of all recorded Tapiolas. A.C.

SrockHAusEN: Kurzwellen; Setz die Segel zur Sonne. The Negative Band. [Carl Stone, prod.] FINNADAR SR 9009, $6.98. Tape: 910I CS 9009, $7.97; TP 9009, $7.97.

Short Wave is a longish work (36:40), here played on percussion, piano, saxophone, and various electronic instruments by a group of six young men recently students at Walt Disney's California Institute of the Arts. As ig the case with many works of Stockhausen, the score consists of signs telling the performers what to do rather than notation of any kind, but among these signs there are so many bypasses and exceptions that they almost cease to exist.

The work sounds like a cross between the rasp- and-squeal routine characteristic of electronic music fifteen years ago and the dense, free clotted improvisation practiced by Omette Coleman and some other jazz men five years before that.

Set Sail for the Sun is a much shorter ( 13:26) and, for me, much finer piece, thanks largely to its continuous, hypnotic use of the tam-tam. One of the best pieces of mu sic I ever heard was a composition by La Monte Young consisting of nothing but forty-five evenly spaced and evenly shaded strokes on the tam-tam. Until we get a record of that, Set Sail for the Sun will have to do. A.F.

Strauss, R.: A German Motet, Op. 62; Two Songs, Op. 34. Soloists; Heinrich Schütz Choir of London, Roger Norrington, cond. [Michael Bremner, prod.] ARGO ZRG 803, $6.98.

A paradox: Here are no less than three rarely heard works by a major composer brought to disc for what must be the very first time in well-nigh ideal recordings of performances that cope nobly with the scores' impossible demands-yet the record can be safely recommended only to institu tional libraries and perhaps fanatical Straussians and ambitious choir-trainers.

The plain fact is that the choral writing here, in as many as sixteen parts (and in the German Motet calling for soloists in addi tion) is just too thickly complex for aural only comprehension, let alone immediate enjoyment. There are genuinely beautiful, deeply moving passages in these intricate settings of poems by Rückert and Schiller, and Norrington's fine British choir gives [...]