After twenty years of rumors concerning a mystery Soviet pianist of enormous power. Americans are finally about to hear him. Here is an exclusive HF interview with the Russian musician.

by Barry James and Vadim Yurchenkov

IN 1955, WHEN SOVIET PIANIST Emil Gilels first appeared in the U.S., he brought word of a young colleague who was capable of the most marvelous pianistic feats. Thus, sprouting from this august source and nurtured by a sparse handful of difficult-to-obtain recordings, the legend of Lazar Berman, pianist of the grand romantic style, took root in the West. But through the years Berman has remained an enigma, partly because of his meager discography and partly because of the limited scope of his rare visits outside the Soviet Union.

He has been to Italy several times, and enthusiastic reports of his appearances there filtering slowly to the U.S. have contributed to the sense of awe and expectancy that seems to surround him.

Beginning this month, American audiences will have the opportunity of hearing-and seeing-the legend unfold into reality: Lazar Berman, at age forty-five, will tour this country for the first time.

The shy and introspective pianist seems acutely aware of the importance of the occasion, calling it "a big unknown and perhaps a big changing point for my career." Coincident with Berman's tour, several of his new recordings will become available here. CBS, through an arrangement with Melodiya, will re lease a two-disc reissue of the Liszt Transcendental Etudes (re-recorded in 163 to replace a 1958 version) and a recently made recording of the Sonata in B minor, the Mephisto Waltz, and Venezia e Napoli, all by Liszt. Deutsche Grammophon will release new recordings of the Liszt Concerto No. 1 and of the Tchaikovsky Concerto No. 1 made with Herbert von Karaj an and the Berlin Philharmonic.

Born in 1930 of a Jewish family with an artistic, intellectual mother and a working-class father, Berman was barely two years old when he began to study the piano. His teacher (who was his mother) entered him in his first talent competition in 1933. Leningrad cultural authorities, recognizing an unusual talent, assigned Prof. Samari Sayshinsky as the boy's teacher. Shortly afterward Berman was placed in a special group of children who were to be trained in music under the aegis of the Leningrad Conservatory.

In 1937 he appeared in a festival of young talent at the Bolshoi Theater in Moscow and at just about that time made his first recording. (He still owns a copy of this rare 78-rpm disc: Fantasy by Mozart performed by "Lialik" [a diminutive] Berman and Mazurka by L. Berman-one of his few attempts at composition.) After the Bolshoi appearance, authorities insisted that the youngster and his family move to Moscow, where, at age nine, he was accepted into the Central Music School as a pupil of Alexander Goldenweiser. Goldenweiser, an arch romantic who has been the largest single influence on Berman's playing, remained his mentor for the next two decades. In 1948, Berman entered the Moscow Conservatory, spending eight years in graduate and postgraduate studies, still under Goldenweiser. He then entered international com petitions and won first prize in Berlin, third at Budapest, and fifth at the Queen Elisabeth competition in Brussels-an experience that prompted him to become a founder of the U.S.S.R.-Belgium Friendship Society. He joined the Moscow Phil harmonic [not the orchestra, but an agency that operates orchestras and other ensembles and rep resents artists] in 1958 and began making concert tours throughout the Soviet Union as well as occasional appearances in the countries of Eastern Europe.

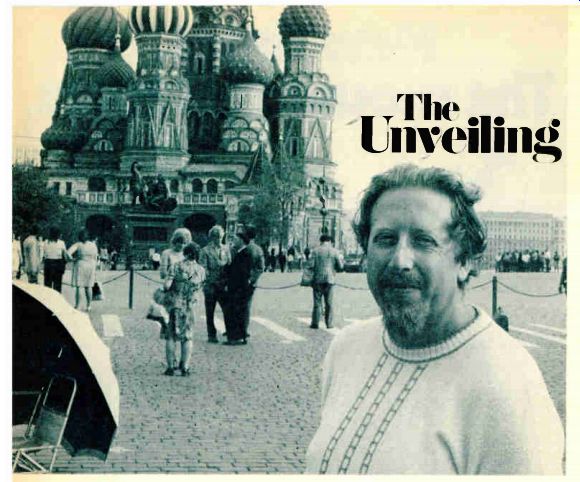

Today, Lialik (some of his friends still call him that) is a large, portly man with a shock of sandy hair, penetrating gray eyes, and a Mephisto-type beard that makes him resemble a Russian Orthodox priest. He is quick to smile, with a flash of gold-capped teeth, and speaks easily with a mellifluous voice in Russian, French, and a little Italian, which he is now trying to learn. Despite the impression of passivity--or even laziness--that Berman makes on a casual observer, he is at times a virtual wellspring of energy (during his last tour of Italy he gave twenty-three concerts in thirty two days). But as with many artists, these peaks of fiery temperament and passionate tension are temporary, set off and sustained by inspiration. With out this, his creativity and enthusiasm seem to flag.

Berman's private life (which he prefers to keep private) centers around Valentina, his second wife, his five-and-a-half-year-old son, Pavel, and their home. His hobbies include stamp- and coin collecting. The small circle of friends that he and Valentina share consists mainly of conservatory teachers and people he has met through the U.S.S.R.-Belgium Friendship Society.

On tour, Berman likes to walk the streets and visit the museums of new towns. "I try to see as much as I can When traveling," he says, "new and exotic things, different people, different customs.

Life is not music alone, and one should not be sub merged completely in one's profession. Only by being an all-around person can one be a good musician." These are the basic facts about Lazar Berman, but they do not tell enough. What kind of man is he-really? How does he approach music? What music does he best like to play? To dig deeper and explore questions such as these, we visited and interviewed Berman several times. This is a composite of those interviews:

HIGH FIDELITY: How did you get started playing the piano?

Berman: My mother began to teach me when I was a little past age two.

HF: Then your family was musical.

B.: My mother was. She hpd studied piano at the St. Petersburg Conservatory under Isabella Vengerova-at the same time Prokofiev did, by the way.

HF: When did you first play in public?

B.: It was in 1933, as I recall. I was about three and a half-still too young to read and write-and Mother entered me in a talent competition.

HF: How well did you play at that time?

B.: Oh, well enough that the authorities in Lenin grad wanted me to have training. There was a special group for children at the Leningrad Conservatory, led by Prof. Samari Sayshinsky, and they put me in that. I remember I played by ear; I couldn't read written music until I was eight. Incidentally, my son Pavel is just five, and he plays the violin and can already read music. Our group was much like a children's music school today, though it was quite a collection of prodigies. Daniel Shafran, the cellist, Yuri Levitin, the composer, and Mark Taimanov, who is a chess grand master besides being a pianist, were in the group too. Unfortunately we were all dispersed during the war. It was a hard time, and many of us gave up music.

HF: What happened then?

B.: In 1937 I played in a talent festival at the Bolshoi. After that my family moved to Moscow, and I went to the Central Music School. That's when I started studying with Prof. Goldenweiser.

HF: What happened to you during the war?

B.: Well, Moscow was very close to the front, so they moved us to Penza. I studied with Prof. [Theodore] Gutman there. Things were not so bad for us considering the circumstances--we were safe, and we ate decently, although I sometimes had to practice with no heat. But what else was there to do? Anyway, they had moved some government offices, some embassies, some theaters temporarily to Kuibyshev, which isn't very far from Penza, so I got to play a performance there. I remember I played the Grieg concerto with the Bolshoi Theater Orchestra.

HF: Was that the first time you played with a symphony orchestra?

B.: No, that was a little earlier--in 1940. It was the Moscow Philharmonic under Grigori Stolyarov; we played Mozart's Concerto No. 25.

HF: And after Kuibyshev?

B.: I returned to Moscow in 1943, after the siege--again with Goldenweiser's class. From 1948 until 1953 I studied at the Moscow Conservatory as an undergraduate, then in postgraduate status until 1957. Since then I have been a soloist with the Moscow Philharmonic [the concert agency], touring the Soviet Union and sometimes Eastern Europe.

HF: When did you first play abroad?

B.: That was in 1951 at the International Youth Festival in East Germany, and I was fortunate enough to win first prize in the pianists' contest. Then I had a concert tour of Czechoslovakia and participated in competitions in Budapest and Brussels. I really enjoyed Brussels.

HF: What did you do during the 1960s? It seems that you were a good deal less active than before.

B.: Yes, that is true. The '60s were slack years for my artistic activities. I did not sign with Melodiya, I had no concert tours abroad, I didn't perform much at all in public. I was very much involved in contemplation and thought, and my artistic out look changed.

HF: Your mention of Melodiya brings up another point: How is it that a pianist of your stature has recorded so little?

B: I have mixed feelings about recording. A record is like a piece of paper-easy to fill, but difficult to fill well. I only want to record what I do best. Then again it's hard for me to retain concentration and interest when I'm recording. For example, in 1967 it was suggested to me that I record all the Rachmaninoff preludes. I went to Melodiya with the idea, and they approved. But somehow I just couldn't keep it going--I lost inspiration, I guess.

The playback is another hard thing. I cannot listen to myself playing. It's too strenuous-like hearing myself as a stranger. There is too much of my soul in it. It's easier just to play the music.

HF: Can you think of any music that you particularly want to record in the future?

B.: Well--yes, the Liszt concertos, Prokofiev's First, Rachmaninoff's Third, Beethoven's Fourth, and the Scriabin. I have never recorded with an orchestra, and if I could do all this I would be happy.

[As of now Berman has recorded Liszt's Concerto No. 1 and Tchaikovsky's Concerto No. 1 with Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic.]

HF: What about travel? Why haven't you per formed more outside the Soviet Union?

B.: I wasn't invited. It is not usual for Soviet artists to travel abroad without a specific invitation.

HF: Is that how your trips to Italy came about?

B.: Yes, as far as I know. There was a group of mu sic lovers in Milan who had heard some of my records and liked them, so they arranged for me to be invited.

HF: Were your performances in Italy successful?

B.: Very. They liked me, and the invitations kept coming. In 1971 my usual concert audiences in Italy numbered 300, perhaps 400 people. Three years later, I was getting about 2,500 at every con cert. Italy has become almost like a second home.

HF: And what of your tour to the United States--was it arranged the same way?

B.: Just about. Jacques Leiser [the New York con cert manager who is handling Berman's U.S. tour] somehow got hold of a record of mine [a recital al bum of works by Chopin, Debussy, Ravel, Rachmaninoff, and Scriabin, reviewed by HIGH FIDELITY, August 1962]. Then he came here to Mos cow and arranged for the tour. I am delighted about the whole thing, of course-and a little apprehensive too. It's a big undertaking and a big un known, perhaps also a big changing point for me.

One thing that worries me is that Steinway pianos [of European manufacture, slightly different from those made in the U.S.] may not be available everywhere in the U.S., and I am not familiar with U.S. and Japanese pianos. I worry a lot about pianos.

HF: Let's talk more directly about you and your music. What about your career-are you happy with it?

B.: Well, my artistic way is quite uneven. I am a nineteenth-century man, a virtuoso, so to speak.

For many years I was carried away with virtuosity, with naked technique, particularly while at the conservatory. My speed became a legend, and I really could play the coda of Chopin's B minor Sonata in fifty seconds. My friends checked it with a stopwatch. It was unfortunate, but we really set up contests, made bets, etc. The only excuse for this was our youth--we thought music was like soccer or something. I thought little about sound, only fingers, speed, perfect notes. The harder a passage was, the more it appealed to me. Of course, after a while, the machinery began to vanish. Then I began to learn and practice sound. I studied recordings of pianists and even singers. I wanted to approach the cantilena as closely as possible; I wanted melodiousness of phrase. By now I can do a great deal of this. When an Italian critic said my piano was better than my forte, I was happy. I was overjoyed when my playing was compared to bel canto. I had been working for that for ten years.,

HF: Would you say that you have one favorite composer?

B.: No-no single favorite. But I do have a favorite style of interpretation. For me, the best style is the one with the most heart and the least possible academism. As a rule I love contrasting music-the interplay of soft and loud. For these reasons I am more than anything a lover of the Romantics, particularly Liszt, Schumann, Rachmaninoff, early Scriabin, Prokofiev. And of course there is Beethoven. To my way of thinking he is usually interpreted far too academically, too smoothly. Every one stresses Beethoven's classicism. I try to show him as a man of passions. After all, Beethoven and Mozart loved, suffered, enjoyed, became depressed, joked. Why is their music to be interpreted in a framework? And why go crazy when playing Liszt or Chopin? All in all, I try to interpret the Romantics more sternly and the Vienna classics less so. And what is classical, anyway? When I read the old authors, I see that fashions have changed-hairdos, dresses. But people are the same.

HF: And what about modern music?

B.: Well, for me modern music ended with Prokofiev. I don't say that other new music is bad, but frankly it is not my métier. Perhaps it all depends on the music one was brought up on. My back ground was Bach, Mozart, Chopin, and Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff, and other Russians.

Today seven-year-olds play music that seems awfully complex to my ears--Prokofiev, Kabalevsky, Bàrtok. Personally, I prefer finding new things in old music to playing new music.

HF: All right. What did you discover in Liszt, for example?

B.: Once, thirty years ago, I was a slave of my hands. They could do anything, so I played Liszt much too fast. Audiences got caught up in the avalanche of sound and would forgive other short comings. Liszt wrote real virtuoso music. Now I try to spiritualize this element; I am the master of my hands. There is even some reserve in my tempos. I try to leave time for the work to be heard, for its contents be digested.

Likewise I've changed my views about Tchaikovsky. I've dropped the bravura interpretation of the First Concerto. I've read a lot of his writings, and I think I understand his soul. Tchaikovsky was not a pompous composer, but a lyricist. So that's how I perform his First Concerto. He didn't put all that grandeur there--it was Bülow. Tchaikovsky devised a modest beginning, with the sound growing from there. In the original autograph score the opening is to be played lyrically and heartily, and that is the way I try to play it. The usual interpretation of the middle of the second movement also, to my mind, goes against the composer's wishes. It becomes a phantasmagoria, with à lot of [E.T.A.] Hoffmann in it. But it is first of all a waltz--pretty and cozy, easy, sincere and hearty. Liszt might have perceived that piece in a fantastic way, but not Tchaikovsky.

HF: Do you have any idols in the world of the piano?

B.: Of course. Every musician has. I could name many, but keeping it short--Sofronitsky, Michelangeli. And by her devotion to art (so unattainable for me), Maria Yudina. I do not seek to become like them. I simply know that there have been such phenomena-that it is possible for human beings to play that well.

------------

Behind the Scenes

Berman records the Liszt B minor Sonata before the organ pipes of the former

Anglican church that is now Melodiya's main recording studio in Moscow.

Berman Before the Mikes When, on the hot evening of May 26, 1975, I entered the Melodiya recording studio on Stankevich Street in Moscow, Lazar Berman was already there, ready to record the Liszt B minor Sonata. Since the workday at Melodiya ends at 6 p.m. and the session was scheduled for 7, most of the staff had gone, leaving just recording engineer Valentin Skoblo and his assistant.

The building that houses Melodiya's main recording facility is an Anglican church that was built seventy years ago and converted for recording in 1960. In its 500-square-foot hall all sorts of recordings have been made-sym phonic, chamber music, choral, and pop. Ray Conniff, incidentally, recorded here late in 1974 with a Russian chorus and band.

Skoblo, who is forty-three, has been in the business for over twenty years and is an old friend of Berman's, the two having worked together many times. The engineers attached to this studio are generalists, able to record practically all genres of music. Each, however, has his own predilections, and Skoblo is predominantly for classical music. He has handled most of the piano recording in Moscow in re cent years.

As Berman was warming up, Skoblo and his assistant were arranging microphones around the Steinway grand-two Neumann mono M 269s and two stereo SM-69s. Then they began to surround the pianist with a " Chinese wall" of panels. When questioned about this, Skoblo replied that high and low frequencies do not record very well in this studio and that, while this is. acceptable for pop music, different circumstances are needed for classical. " Over the past fifteen years we've learned to compensate for it pretty well," he added.

With the pianist properly surrounded (it looked awful, but audio quality is the main thing, after all), Skoblo stopped for a last quick word with him: "Shall we record in segments?" No. Berman wanted to record the whole sonata in a single take.

I left Berman alone with the piano and made my way to the control room, which was equipped with a twenty-four-input Neve console and Swiss-made Studer C-37 recorders. He took the first three notes-and stopped. He seemed disturbed, as if he had heard some noise. Now we too could hear the noise, which seemed to come from a duplicating room underneath the studio, and the assistant went down to stop it. The time was 7:40. Once again Berman put his hands to the keys: single initial notes-the B minor Sonata.

Berman truly loves the music of Liszt, and he was playing it as only he can: quietly, yet seriously, with just the right tone, his grand piano singing. Passage followed passage. Then there were a few minor slips, an arpeggio missed in one place. But on the whole--good. It was 8:10.

He had played the sonata in exactly thirty minutes.

Skoblo invited the pianist in to listen to the take, and Berman entered, his forehead shining with sweat. He joined Skoblo at the console, and the playback began with the two poring over the sheets of music before them. Skoblo pointed out each fault as it occurred, whether in playing or recording. Berman nodded his head and said, "You know, the second take is always the best; it is somewhat of a rule with me. Let's try the whole thing again." Then he added, "I'm glad there is no vocal of mine on the tape. Sometimes I get carried away and be gin to croon." Recording resumed, and surprisingly enough it went a trifle differently. But that trifle was worth a lot: touch became freer and more natural; inaccuracies disappeared; things became easier and more human.

Another playback session. Skoblo, more enthusiastic now, asked him to play the middle of the sonata again, just to be sure. Berman re turned to the keyboard and started to play, but he could not stop and so played right to the end. He looked tired and sweaty. But, satisfied with his playing, he was laughing and joking.

The time was 10:30; in just one three-hour session, Berman had recorded the entire thirty minute sonata. V.D.Y.

-------------

-------------

(High Fidelity, Jan. 1976)

Also see:

Classical: Milstein's Bach ... Die tote Stadt ... Beethoven choral works.