reviewed by:

ROYAL S. BROWN ABRAM CHIPMAN R. D. DARRELL PETER G. DAVIS SHIRLEY FLEMING ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE CLIFFORD F. GILMORE HARRIS GO LDSMITH DAVID H AMILTON DALE S. HARRIS PHILIP HART PAUL HENRY LANG ROBERT LONG ROBERT C. MARS H ROBERT P. MORGAN CONRAD L. OSBORNE ANDREW PORTER H. C. ROBBINS LANDON HAROLD A. RODGERS J OHN ROCKWELL PATRICK I . SMITH SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

---- Heinz Holliger A prodigally gifted oboist.

BACH, C.P.E.: Concertos for Oboe, Strings, and Continuo: in B flat; in E flat. BACH, J . S.: Sinfonias to Cantatas Nos. 12 and 21. Heinz Holliger, oboe; English Chamber Orchestra. Raymond Leopard, cond. PHILIPS 6500 830, $7.98.

A coolly objective evaluation of any current Holliger recording is quite impossible for those of us who find this prodigally gifted young Swiss oboist another Pied Piper of Hamelin whose first notes cast a spell potent enough for him to lead us--ecstatic--where he wills.

This time he again draws us back into the High Baroque to surprise us with a new, or at least refreshened. appreciation of the art of Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. One of C.P.E.'s two fine oboe concertos. W. 165 in E flat, is by no means unknown (indeed, one of its earlier recordings was by Holliger, in 1966 on Monitor), but the other, also com posed in 1765, will be new to most of us if it isn't actually a recorded first. Yet what points up the wealth of both invention and feeling in these works is Holliger's inspired prefacing of each with a shorter piece for the same combination of oboe and strings by Papa Bach himself. Even the composer of the rhapsodic sinfonias from the cantatas Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen and lch hatte viel Bekiimmernis would be the first to agree that his own noble eloquence is fairly matched by the slow movement of the B flat Concerto bearing the hallmark of a distinctively different individuality. Jo hann Sebastian might well be proud too of Carl Philipp Emanuel's consistently skilled craftsmanship and might even envy a bit a jaunty swagger rarely evident in his own lively but never quite as casual moments.

No one familiar with Holliger's Bach/ Couperin/Marais program (Philips 6500 618. June 1975), or for that matter any of his other previous recordings, needs to be told about his flawless executant artistry or the delectable piquancies of his timbre colorings. And since he is well-nigh ideally accompanied and recorded, the only opening left here for the mildest of complaints is that the protean Holliger is not given the opportunity of writing his own jacket notes. as he has done so ably in some earlier releases. He certainly would have given us better source documentation, including the W (for Alfred Wotquenne thematic cata logue) numbers for both concertos. R.D.D.

BARTOK: Violin Works, Vols. 1-2. Denes Zsig mondy, violin; Anneliese Nissen, piano. [Har old Powell, prod.] KLAVIER KS 535 and KS 542, $6.98 each. vos. 1: Sonata for Violin and Piano. No. 1; Rhapsody No. 1; Six Romanian Dances. Vol. 2: Sonatas: for Violin and Piano, No. 2; for Solo Violin.

Denes Zsigmondy is an intense violinist who gets hair-raising effects when playing on the bridge, or pizzicato, or with mute, etc. When simply bowing in the ordinary manner, he is less convincing and is prone lo flatness. Anneliese Nissen, no mere "accompanist." plays up a storm at the key board; she also overarpeggiates chords, just as her husband overslides-Bartok is quite specific in indicating glissandos, appoggia turas, and the like. Zsigmondy and Nissen try their best to keep up with Bartok's fre quent tempo changes, but a tendency to exaggerate causes them to lose over-all direction.

Probably the most practical alternatives are the Stern/Zakin disc of the two num bered sonatas (Columbia M 30944) and Ricci's account of the unaccompanied sonata (Stereo Treasury STS 15153). Stern is in his finest virtuoso fettle here, dead in tune all the way and driving the music with almost barbaric thrust, even if some of the tricky tempo switches along the way are blended out. Zakin's usual self-effacing discreetness is actually a plus here, since it makes it possible to hear both instruments all the time. Ricci may not be the ideal per former for the solo sonata (he has to slow down to maneuver the entrances in the monstrously difficult fugue), but he's technically better than Zsigmondy and his budget-priced disc offers a valuable sampling of twentieth-century violin literature, with works by Hindemith. Prokofiev, and Stravinsky.

Andre Gertler has recorded most of the Bartok violin repertory several times over, and his current Supraphon series (SUAST 50481, 50650, and 50740) includes the un numbered 1903 violin-and-piano sonata, the real "No. 1." Much as I respect Gertler's idiomatic musicianship, however, his playing strikes me as a little low-powered for this knotty stuff. If cost and convenience are no concern, you might look for the long out-of-print imported coupling of Menuhin's solo sonata and Sonata No. 1. and the various Szigeti/Bartok performances- Sonata No. 2 and the rhapsodies on Van guard Everyman SRV 304/5, the Romanian Dances in the six-disc Columbia M6 X 31513. Wonderful performances all, but not a very practical solution. A.C.

Beethoven: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra: No. 2, in B flat, Op. 19; No. 4, in G, Op. 58. Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich, piano; BBC Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 6500 975, $7.98.

Comparison: Fleisher, Szell /Cleveland Orch. Col. MAX 30052 These performances complete the Bishop Kovacevich/Davis Beethoven concerto cycle; No. 4 is possibly the best thing in it.

The suitably brisk tempos of No. 2 are not always perfectly maintained, and Bishop Kovacevich unfortunately adopts a rather mincing, staccato approach to this admittedly classical work, as he often does in Mozart. Davis' reduced orchestra does yield felicitous woodwind balances, but overall I prefer a bolder conception, like the Fleisher/Szell and the Schnabel/Do browen (in Seraphim IC 6043). In No. 4, however, Bishop-Kovacevich blends toughness and athleticism with introspection. Davis provides rhythmically taut, crisply organized orchestral support, and the recorded sound is bright and impactive. All that is missing is the extra eloquence of the Fleisher/Szell performance, slightly warmer in color and richer in nuance.

Philips has now boxed the Bishop-Kovacevich / Davis cycle as 6747 104 (four discs for the price of three), though without the sonatas that originally appeared as fillers for Nos. 1 and 3. On rehearing, I am somewhat more impressed by the previously issued performances. These are truly ensemble conceptions, with excellent solo/ tutti dovetailing and obvious comprehension on the part of both soloist and conductor. Bishop-Kovacevich uses Beethoven's cadenzas and is scrupulous about such de tails as pedal markings. For me, though, the contemporary standard in these works re mains the Fleisher/Szell set, for its un matched immediacy of emotional response, rollicking humor, and to-the-manner-born ease. At $13.98, the Columbia set is a remarkable bargain.

Save for some excessive resonance in the chromatic runs of No. 3's first-movement cadenza (which may simply be over pedaling), the engineering is very fine

-------------------

The Bach Cantata Project Reaches Fifty

by Andrew Porter

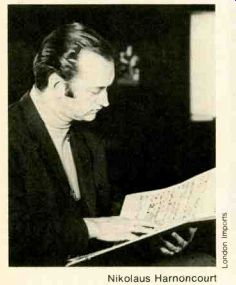

------ Nikolaus Harnoncourt

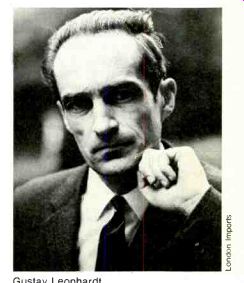

With these three volumes, Dos Kantaten werk, Telefunken's complete recording of all the Bach cantatas, has reached its half century and marks the occasion by including in Vol. 13 three indices of the achieve ment to date: the first fifty cantatas classified by the church year, by chronology of composition, and by number. The level of execution remains as high as ever. There is no trace of a routine slog through the Ge samtausgabe. The character of each cantata, and of each number within it, is vividly realized. For those who may be coming in at this reel, let me recall briefly that the works are sung by all-male forces and are played on instruments of Bach's day, or re constructions thereof, by two masterly ensembles, Nikolaus Harnoncourt's Vienna Concentus Musicus and Gustav Leon hardt's Amsterdam-based Consort.

Comparisons with conventional modern performances, using what Harnoncourt insists are basically late-nineteenth-century instruments, are beside the point. They may, they often do, have great expressive merit-but simply to listen to the opening chorus of No. 39, and the colors of the chords as they drop in turn from recorders, eighteenth-century oboes, and strings, should be enough to convince anyone that with these Telefunken performances we enter a new (or old) and better world. The sound of these performances is so beautiful; and, with two small reservations mentioned below, the recording quality is ideal.

But the beautiful sounds are part of the sense. Listening to the pointed, eloquent articulation of the solo violin and the oboe, as they accompany the alto in the first aria of No. 39, makes the kind of Bach playing we usually encounter sound like a rough approximation, or at best a transcription.

In No. 39, with an expansive opening chorus and a picturesque use of instruments, and No. 40, a jubilant cantata for the Second Day of Christmas, and then again in Nos. 45 and 46, the Hannover Boys Choir, previously heard in Vol. 9, returns to the series. (Who the choral tenors and basses are we are not told.) It is an excellent ensemble. firm and forthright, clean in articulation, and it provides a good soloist, who, like the other trebles of the series, lacks only a trill to be completely satisfying. The tenors strike me as a shade light.

Rene Jacobs is a wonderfully deft alto. I last heard him in a bouncy comic-servant role in Cavalli's Erismena, at the 1974 Holland Festival; he is a singer to cure anyone's possible dislike of countertenors, with a voice firm, virile, pleasing in timbre, perfectly secure, sounding true divisions not at all fluttery but struck out exactly as if by little hammers. He has a good trill. He is the only singer who ventures little embellishments of the vocal line, in the aria of No. 45 (a marvelous duet with Frans BrUggen's flute). The voice "peaks" a little at C and above, acquires a force that can disturb the evenness of line. There are moments, in Nos. 39 and 45. when I feel he is ar-ti-cu-lating the melody a little too carefully-like an organist giving out a fugue in a very resonant building-but this is in keeping with Leonhardt's general approach.

At times--the outstanding examples are the opening chorus and closing chorale of No. 39--Leonhardt seems to sacrifice line to clarity of attack; the chorale is given out note by note. In blurry church acoustics, the echo would join the notes into a melody; the Telefunken recording quality is not at all dry, but not so resonant as to call for detache precision. Leonhardt's endings can also be abrupt--especially the close of No. 46, which seems suddenly to breakoff. But one can usually find some reason in the mu sic that has prompted his particular treatment, for he can also be large and broad.

The opening chorus of No. 45, a long "expository" treatment of the text, richly scored, is accorded a radiant performance.

As we proceed to No. 41, a rollicking New Year (or Feast of the Circumcision) cantata, and No. 42, for Low Sunday, the Sunday af ter Easter ("At the Sunday Quasimodoge niti," Telefunken's English "translation" calls it; I had to consult a German-English dictionary to see what was meant), a difference between Leonhardt and Harnoncourt becomes apparent. It is implicit throughout the series, but highlighted here, fortuitously, by the juxtaposition of pieces and by recording quality. The opening chorus of No. 41 is a brilliant affair with trumpets and drums, and the first movement of No. 42 (perhaps to spare a choir worn out by its Passion and Easter tasks) is an instrumental sinfonia in Brandenburg vein; each of them is here fiercely, even a little roughly, presented, with a touch of harshness in the recorded sound. This emphasizes the difference between Leonhardt's delicate precision and meticulous, beautifully calculated detail and Harnoncourt's greater readiness to let things go and let things flow. I do not want to make too much of it, but I imagine that anyone who attentively follows the series will soon be able to spot which conductor is in charge.

The anonymous Vienna choirboy of Nos. 41 and 42 strikes his words with delightful conviction. There is a slight edge around the recording of Paul Esswood, the countertenor of the Vienna recordings, almost as if he had been tizzed up with artificial resonance, and I remarked this again in Nos. 44 and 48. He starts "peaking" a little higher than Rene Jacobs, from D upward. Kurt Equiluz, the tenor of the series from No. 41 to No. 49. is lyrical, expressive, altogether satisfying. The recitative and aria of No. 45 is an especially taking example of his direct, clear singing-candid, fervent, but not hectoring. Ruud van der Meer, who joined the enterprise at Vol. 10, is a bass with an urgency of utterance that makes one prick up one's ears every time he enters--in Nos. 41, 42, 43, perhaps most of all in No. 44 when he sings "Es sucht die Antichrist, dass grosse Ungeheuer, mit Schwert und Feuer." Outside Dos Kantatenwerk his name is unknown to me; I want to hear more of him.

In Vols. 12 and 13. the soloist of the Vienna Choir Boys is allowed an individual credit, and Peter Jelosits deserves it. He is a treble who commands long, clean, lovely divisions. He has a beautiful tone and excellent coloratura. There is no thinning out as he rises to A. He essays no trills (an occasional mordent at a cadence is the most he ventures), yet one feels that with a little encouragement he could easily have managed them. With cogent words he announces, in No. 47, the qualifications for calling oneself a real Christian. As the Bride in No. 49 ("Ich bin herrlich, ich bin schan") he sings with sparkling tone.

The bass soloists have been the most changed members of the enterprise: Max van Egmond through the first five volumes, and then appearances by Walker Wyatt.

Siegmund Nimsgern, Ruud van der Meer.

and now in Vol. 12 Hanns-Friedrich Kunz.

They are all good. Van Egmond, in Nos. 39 and 40, expresses the words exquisitely but without overemphasis. In No. 46, Kunz has a storm aria. "Dein Wetter zog sich auf," with slide-trumpet obbligato. which he sings brilliantly. (The trumpeter and his instrument are unidentified in the otherwise detailed personnel lists.) In Vol. 13, Harnoncourt surprises us by making a long "romantic" rallentando to the close of the first chorus of No. 47. No. 49 (Dialogus), without chorus, is a duet cantata for bass and treble, Bridegroom and Bride (the text for the day was the parable about the wedding guest who didn't have the right clothes and was thrown into outer darkness. Matthew 22)-an aria apiece and a final duet in which Master Jelosits, unsupported, holds a chorale line with steady shine through the figuration of the bass and the orchestra. No. 50 is a torso, a magnificent double chorus with trumpets and drums.

The material that accompanies the al bums has been rightly praised: One booklet contains brief introductions to each cantata (in Vol. 13. Ludwig Finscher takes over from Alfred M IT as author), a learned essay on some aspect of the cantatas as a whole, and texts with English and French translations: another, full scores of the works concerned. All the same, the material is not quite as good as it could be. The cantata texts are printed not as verse, but in run-on style. The English is not a translation, but a rhymed singing version that is often ingenious but sometimes not quite true to the German original. ("I am joyous. I am glad,/for I know my Saviour loves me" is hardly a precise rendering of "Ich bin herrlich, ich bin schand Meinem Heiland zu entztinden.") The lesson for the day is not always identified.

The scores of Nos. 39, 41. and 43-45 are given in reductions of the Neue Bach Aus gabe edition, six pages of the original clustered on one of the new format, legible with keen eyes in a good light. The others are in a face similar to that of the NBA. a little less spidery as regards the notes but with the words slightly less sharp. These non-NBA scores do not always accord with the performances (though differences are usually pointed out in the booklets): In No. 46, Leonhardt omits the trumpets and oboes of the first chorus, as a later addition; in No. 47, the obbligato of the soprano aria is played by a solo violin (an autograph part, probably for violin, survives), but the printed score still gives it to organ. There are also verbal differences between score and performance in that aria and in the subsequent recitative; "Staub" is changed to "Stank"-man becomes "muck, stink [in stead of "dust"), ash, and earth." The essays are: Vol. 11. Detlef Gojowy on emblem books and their influence on the imagery of Bach's texts; Vol. 12. Emil Platen on the structure of the opening choruses; Vol. 13, Christoph Wolff on the use of the organ. The first is particularly interesting, but the English translations of all three are graceless to the point of being un readable. Non-Lutherans may also need help with the nomenclature of the church year. I have mentioned Quasimodogeniti above; "At the Sunday Estomihi" is more familiar as Quinquagesima, and "At the Sunday Exaudi" is the Sunday after Ascension. Small points, but worth making, since as the series progresses, its presentation is being improved. Miniature the scores may be. but, being printed now in black on white, they are at least easier to follow than were the buff pages of the first albums.

------ Gustav Leonhardt.

The edition follows the old numerical sequence, which corresponds neither to chronology nor to the church calendar, so any album will provide cantatas from different periods and in different moods. Buy one, and you will probably be hooked; I echo C.F.G.'s advice when he reviewed Vols. 4 and 5: "My strong and unqualified recommendation is to acquire each of these history-making volumes as it appears."

BACH: Cantatas, Vols. 11-13. Various soloists; Hannover Boys Choir, Leonhardt Consort, Gustav Leonhardt, cond. (in Nos. 39, 40, 45, 46); Vienna Choir Boys, Chorus Viennensis, Vienna Concentus Musicus, Nikolaus Harnoncourt, cond. (in Nos. 41-44, 47-50). TELEFUNKEN 26.35269 ( SKW 11), 26.35283 ( SKW 12), and 26.35284 ( SKW 13), $13.96 each two-disc set (manual se quence). vol. 11: No. 39, Brich dem Hungrigen dein Brot: No. 40. Dazu ist erschienen der Sohn Gottes: No. 41. Jesu, nun sei gepreiser: No. 42, Am Abend aber desselbigen Sabbats' Vol. 12: No. 43. Gott fahret auf mu t Jauchzen': No. 44. Sie werden euch in den Bann tun': No 45. Es ist dir gesagt, Mensch. was gut Mt. No. 46. Schauet doch und sehett. Vol. 13: No. 47. We, such selbst erhohet, der soli erniedriget werden': No. 48, Ich elender Mensch. wer word mich erlosen': No. 49. Ich geh und suche mu ye, langen': No. 50. Nun ist das Heil und die Kraft. ['Boy soprano from the Hannover Boys Choir: Rene Jacobs, countertenor: Manus van Altena. tenor: Max van Egmond. bass ' Boy soprano from the Vienna Choir Boys (Peter Jelosits in Nos 43-44, 47-50): Paul Esswood. countertenor; Ruud van der Meer. bass Rena Jacobs. countertenor; Kurt Eguiluz. tenor: Hanns-Friedrich Kunz.

----------------------

(cont.)

throughout, and the remastered No. 1-1 did fiot have the other earlier discs on hand for direct comparison-shows a. definite improvement in dynamic range. The imported pressings are superb as usual. H.G.

[For more on Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich, see this month's "Behind the Scenes."]

BEETHOVEN: Quintet for Piano and Winds, in E flat, Op. 16*; Octet for Winds, in E flat, Op. 1 03'. Rudolf Serkin, piano"; musicians from the Marlboro Music Festival. [" Mischa Schneider, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33527, $6.98 ['from MS 6116, 1960].

BEETHOVEN: Trio for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano, in B flat, Op. 11. HAYDN: Trio for Flute. Cello, and Piano, in G, H. XV:15., Richard Stoltzman. clarinet--; Michel Debost, flute', Alain Meunier" and Peter Wiley, cellos; Rudolf Serkin, piano. [Mischa Schneider, prod.] MARLBORO RECORDING SOCIETY MRS 7, $7.00 postpaid (Marlboro Recording Society, 5114 Wissioming Rd., Washington, D.C. 20016).

The best performance on these discs is not new; the excellent Columbia Beethoven oc tet, first issued in 1960 (coupled with the Dvorak wind serenade), is characterized by split-second ensemble. judicious balances, beautiful tone color, and romping high spirits. The giant flutist Marcel Moyse conducts these stellar players with splendid vitality and the best of good classical taste.

The new coupling for the octet, the Op. 16 Quintet, is a disaster from virtually every standpoint. A quarter-century ago Rudolf Serkin math, a superb recording with members of the Philadelphia Wind Quintet, and I have heard a number of subsequent Marl boro readings that whetted my appetite for this recording. One can sense Serkin's basic influence, but the performance vacillates between pedantic rigorousness and ram bling self-indulgence. Ensemble is often ragged, the rhythmic impulse lags, the wind playing is overblown. Serkin himself ap pears badly off form (the fingerwork is noodly and uneven, ornaments are bumpy, and he often rushes passagework). Far more valuable would be an Odyssey reissue of the Serkin/Philadelphia version; meanwhile, that by Ashkenazy and the London Wind Soloists (London CS 6494) is easily the best available.

Both performances on the Marlboro Recording Society disc are well above the level of the Columbia Beethoven Op. 16.

The Haydn flute trio is excellent: rather se vere coloristically, but full of linear thrust and dramatic tension. The Beethoven clari net trio is certainly praiseworthy, but the performance is a bit straitlaced for so high spirited a work. The excellent clarinetist, Richard Stoltzman, sounds a trifle pinched and nasal here (he can be heard to far better advantage on his Orion recital disc, ORS 73125, November 1973), and I am not fond of the cellist's rather spready. old-fash ioned shifts. Serkin's disciplined pianism binds things together but, alas, also clips the music's wings whenever it starts to soar. H.G.

BEETHOVEN: Symphonies (9); Overtures. Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Georg Solt, cond. [Ray Minshull and David Harvey, prod.] LONDON CSP 9, $50.00 (nine discs, manual sequence).

Symphonies: No. 1, in C. Op. 21: No. 2, in D. Op. 36; No. 3, in E fiat. Op. 55 (Eroica); No. 4, in B flat, Op. 60; No. 5, in C minor, Op. 67; No. 6, in F. Op. 68 (Pastoral); No. 7, in A. Op. 92; No. 8, in F. Op. 93: No. 9. in D minor. Op. 125 (with Pilar Lorengar, soprano; Yvonne Minton. mezzo; Stuart Burrows, tenor, Martti Talvela. bass; Chicago Symphony Chorus)'. Overtures: Coriolan, Op. 62; Leonora No. 3, Op. 72a'; Egmont. Op. 84'. rfrom CSP 8, 1973; ' from CS 6800.19741

These performances are generally athletic and unaffected, and they benefit from the services of a superb orchestra. Less appropriate, to my ears, is the massively rever berant engineering; the classical orchestra would be better served by a leaner, crisper pickup. In the following rundown, the indi vidual performances are discussed in the order of the set's couplings.

The first disc pairs Nos. 1 and 8, and this is one of the better Firsts on modern rec ords. The second movement is a trifle rushed and inflexible, and the third-move ment trio, though aided by some feathery violin playing, is metronomic without being really rhythmic. But I like the opera-buffa approach to the outer movements, and the staccato string playing in the finale has much of the felicitous Rossini-like quality that made Toscanini's First so memorable.

The reduced orchestra's sound is not helped by the brashly inflated acoustics, but detail is good enough. One curious note: Solti's newfound penchant for repeats (the man who recorded a Fourth and Seventh with none whatsoever reportedly now be lieves that every repeat in the symphonies is essential to Beethoven's architecture) leads him to introduce an uncalled-for and structurally disruptive da-capo repeat in the Menuetto.

There is nothing small-scaled about Solti's Eighth, but his red-blooded reading lacks something in point and precision. Detail is again good (you can hear the cellos in the third-movement trio as clearly as on Toscanini's 1952 recording), but it doesn't always add up correctly. Such moments as the beginning of the first-movement reca pitulation and the sardonic fortissimo in terjection of the strings in the second move ment are disappointingly mild-mannered.

A goodish performance, but not to be com pared with Casals ( Columbia MS 6931), Szell (in his cycle, Columbia M7X 30281), and Toscanini (in Victrola VIC 8000; avoid the rechanneled single discs). Only a lu gubriously paced minuet keeps Karajan (DG 2707 013) out of the top, group.

No. 2 occupies a single disc, preceded by the previously issued Egmont, lumbering and turgidly recorded. After a mechanical introduction, the first movement of the symphony is decently paced and con trolled. The Larghetto drags oppressively the tempo is simply too slow, with no give and take in the shaping and little singing quality in the phrasing. The scherzo, though, is bright and well paced, the finale forthright and unsubtle. By far the best Sec ond known to me is Toscanini's 1939 NBC performance (not the one in the Victrola set), but Szell (in his cycle) and Scherchen ( Westminster, deleted) are also worthy. So too is Karajan (DG 138 801), though a bit overrefined.

No. 3 runs to a third disc side; the first movement gets a side to itself because of Solti's broad tempo and his observance of the repeat. (The finale of the Eroica is fol lowed by the first movement of No. 4, which is completed overside.) The opening chords are rather limp, but at least we are spared the nasal cellos of Solti's 1959 Vienna Philharmonic version. Though the basic tempo for the first movement seems much slower than before, there is surprisingly little actual difference; the impression probably results from Solti's currently less frenetic handling of contrapuntal passages.

Save for occasional loss of impetus, this is a good first movement, though Solti still hasn't shown me that the repeat can be taken without straining interest. The extremely broad Marcia funebre is blemished by some fussy, theatrical tenutos at the end, which transform the sublime into the merely sentimental. In the scherzo, Solti still slows down for the trio, but now he makes a gradual, Walter-like transition from his crisp basic tempo. The new ver sion is certainly an improvement, but I pre fer a single tempo for this movement, as with Toscanini, Busch, Weingartner, and Leinsdorf / Rochester. The finale is simply poor: all sorts of studied lengthenings and the like, broken line, and even some lethar gic, imprecise playing.

Solti's 1951 Fourth with the London Philharmonic displayed a sturdy conception: happily the new version is not all that dis similar, save in matters of repeats and engi neering. The slow introduction has a re fined, poised line. The main allegro is well phrased, with every instrumental choir fall ing neatly into place. There is some ravishing pianissimo string playing, and the easing of line just before the recapitulation is similar to Toscanini's and Karajan's, though less subtly gauged. The Adagio suffers somewhat from the long reverberation time, and the reading is slightly amorphous and squarely weighted. The remaining movements recover splendidly (with the third-movement trio taken in tempo), and the playing throughout has wonderful spirit and solidarity. All that is missing is the in comparable shaping of Toscanini and Karajan (DG 138 803), but Solti joins Barn (DG 2530 451) just behind them.

No. 5 is preceded by the previously re leased Leonore No. 3, which is admirably disciplined but lacking in spirituality, with exaggerated contrasts that verge on vulgar ity. The symphony gets a big, burly treat ment. The music of the first movement is robust enough to withstand the muscle-bound tempo and lack of internal shaping; not so the second, saved only by some impressive pianissimo string playing. The third move ment begins with overly sentimental ritards, but the cellos and basses are pow erful and clean in the trio. There is a good transition to the massive finale, which is clear and well judged but somehow unex citing. On the whole, this Fifth is no match for those of Toscanini, Cantelli, and Carlos Kleiber (DG 2530 516). No. 6, contained on one disc, suffers most of all from Solti's generalized ap proach and the gummy, inflated sonics. The quivering trills and other effects, which can re-create the sounds of nature so wonder fully, are neutralized by the bloated tex tures and reproduction. Solti makes some serious errors of judgment: The tenutos at bars 203-4 of the third movement are taste lessly prolonged; the climactic reappear ance of the finale's second theme is beset with a horrid Luftpause; the coda of the fi nale is unbearably sentimentalized by a dirgelike treatment. The London catalogue already boasts a far better Pastoral at budget price, Monteux's with the Vienna Philharmonic (Stereo Treasury STS 15161). By contrast, No. 7 (with CorioIan as a filler) is the prize of the cycle. Solti's Vienna Seventh was the best of the three sym phonies he recorded then; the new version is still better. The introduction, which for merly lumbered a bit, now moves at a per fectly measured tempo. As before, the flute introduction to the vivace sounds fresh (how wonderful to be spared that nasty little comma), and the dotted rhythm is masterfully judged. At several points in the first movement, Solti has noticeably tight ened his rhythmic grip. The Allegretto is ex quisitely paced, the crescendo graded with masterful poise, though some may prefer the more personal, singing second movement of the 1959 version. The scherzo is tre mendous: swashbuckling, magnificently sprung rhythmically, full of verve and deli cacy, effectively contrasted dynamically.

For once the trio is suitably brisk, in the Toscanini manner. The finale, slightly broader than before, now serves as a logical summation of what has preceded it. A mag nificent performance, lacking only the ir replaceable individuality of Casals (re viewed separately this month) and Toscanini.

The coupled Coriolan is shaped and pro jected with clarity and taste. My only quibble, a small one, is with Solti's insist ence on slowing down before both appear ances of the second theme. The sound of Coriolan and the Seventh is the best in the cycle (both were taped in Vienna, but then so was the Sixth): Though there is massive solidity to the low strings, there is also great clarity-note the crisp, frosty definition of the flute in the symphony's first movement.

Separate issue of this disc is worth watching for.

No. 9 (spread over four sides) impresses me even less than when I first reviewed it (May 1973). The rich tutti sound compensates somewhat for the prevailing limpness of the first movement, but the second is horrid, with its rasping overtones from closely miked bassoons and timpani that sound like sledgehammers. The Adagio oozes, with virtually no phrasing at all: the basically direct finale is hurt by an overly fast march and a murky fugato. This is a Ninth for people who prefer a sonic blast to mu sic. Fortunately Solti shows elsewhere--notably in the First, Fourth, and Seventh-that he's capable of more. H.G.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 7. For an essay review, see page 83

BERLIOZ Symphonie fantastique. For an essay review, see page 83

BRAHMS: German Folksongs. Edith Mathis, soprano"; Peter Schreier, tenor.; Karl Engel, piano"; Leipzig Radio Chorus, Horst Neumann, cond.$ [Rudolf Werner, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 057, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). German Folksongs (42); Children's Folksongs (14)'; German Folksongs for four-part chorus (9)s.

This album contains a lot of songs: fourteen Children's Folksongs and fifty-one German Folksongs (forty-two -for solo voice, nine for four-part chorus). No doubt the scale of this venture stems from the current passion for comprehensive documentation. I can hardly believe there are many music lovers who would care to subject themselves more than once to so enervating an experience as hearing these sixty-five absolutely discrete pieces at a stretch. Or even-to speak for myself-hearing a single side's worth. There is simply too little variety of sentiment and sensibility to hold my attention even that long.

In addition, the individual songs are not only fairly undistinguished, but often, be cause of the strophic form in which all are couched, numbingly monotonous, not withstanding Brahms's skill as an arranger. The four musically identical verses of "Sand mannchen" (No. 4 of the Volkskinderheder) wear out their welcome long before the end.

(In light of the obfuscation that Werner Morik brings to his album notes. it should per haps be said that comparatively few of these pieces are authentic folksongs.

Brahms was misled into accepting as genuine a large number of outright forgeries, together with several numbers originally intended as parodies of folksongs and others with no connection to folk music at all--e.g., "Sandmannchen," which derives from a melody in a seventeenth-century Psalter.) Despite all this, the performances here are good. Peter Schreier is particularly expressive and attractive. Edith Mathis, apart from being somewhat lacking in personality, is not always comfortable with the high keys in which most of this music is pitched.

Where the tessitura is comparatively low, however (as in, for example, "Da unten im Thole"), she is often very winning. In any case, she, like Schreier, avoids the disingenuousness and dramatic overemphasis that mark the Schwarzkopf/Fischer-Dieskau performance of the Deutsche Volkslieder on Angel SB 3675. There is also slightly less recourse on DG than on Angel to the dubious practice of dividing up certain songs between the two singers as if they were dramatic scenas.

Karl Engel provides solid accompaniments for Mathis and Schreier. In the four-part choruses, the Leipzig Radio Chorus is very fine. The recording is clear and spacious, though in the Volks kinderlieder, sung by Mathis alone, the acoustic is perhaps too intimate.

Texts and translations. The latter, being singing translations, are only approximate in meaning. Though un-credited, most of them are by Albert Bach and were commissioned by the original Berlin publisher when the songs were new. The surfaces of my review copy were rather noisy, a sur prising fact, given DC's scrupulousness in such matters. D.S.H.

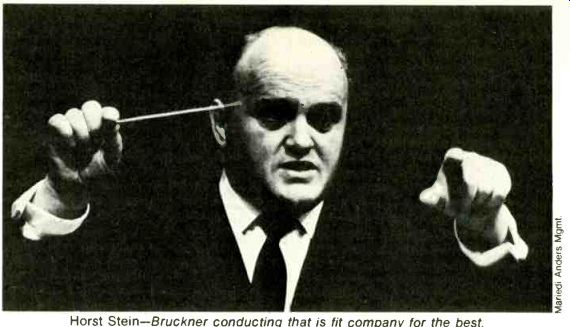

Bruckner: Symphony No. 6, in A (ed. Nowak). Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Horst Stein, cond. LONDON CS 6880, $6.98.

Comparisons Haitink/Concertgebouw Phi. 6500 164 Steinberg /Boston Sym. RCA LSC 3177

It was only four years ago that the Bruckner Sixth finally received, with the release of the Haitink/Philips and Steinberg/RCA editions, recordings with the thrust, power, and brilliance for which the music had long cried out. As one might have predicted from HorstStein's Bruckner Second (November 1975), his Sixth is fit company, and even improves on them in a few respects. For one thing, London's engineering has an immediacy and warm expansiveness lacking in the somewhat dry RCA and backwardly miked Philips acoustics. (For once the Haas and Nowak editions do not differ significantly, so the three performances are textually more or less comparable; score references below are to Nowak.) Though the first movement is properly heroic and assertive in all three readings, only Stein observes the gear change for the lyrical counter-theme, and without losing momentum; Steinberg and Haitink all but ignore the bedeutend langsamer (cue B). Stein continues his masterly shaping in the well-judged acceleration and return to the initial tempo (cue M). Both the Vienna Phil harmonic and the Concertgebouw are a bit tidier in ensemble in this movement than the Boston Symphony, whose violins' eighth-note ostinatos at the very beginning are slightly nervous.

-------- Horst Stein--Bruckner conducting that is fit company for the

best.

I wish Horst Stein had subdued his slightly too full-blooded low strings in the opening of the Adagio; subsequently there is little to fault in this sensitive and well-shaped interpretation. The lyrical phrasing of the closing pages could hardly be bettered.

Haitink is a bit less ardent in this movement. and the Concertgebouw tone is cooler and more restrained. Steinberg's well-performed Adagio is the only uninterrupted one on disc; both Stein and Haitink have side breaks at G-relatively tolerable.

In the Scherzo, Haitink's swift reading captures all the mercurial shifts of color, thanks to the Concertgebouw's superior coordination. Steinberg and Stein set broader tempos, but the former maintains a taut and swaggering gait; Stein's under articulation of the low-strings march rhythm accompaniment deprives the movement of its sense of menace. In the trio, only Stein observes the langsam marking, achieving a jovially parodistic effect that contrasts with the martial impact of the faster Haitink and Steinberg readings.

The somewhat ambling finale needs all the animal energy it can get to hold together, and all three conductors provide this. The Boston version is notable for its brash abandon, while the Concertgebouw attacks the sudden fortissimo outburst for trumpets and horns at bar 22 with such calm precision that I still find it the most sheerly terrifying moment in all Bruckner.

The new version is especially impressive for its steady control of transitional pas sages and for the secure coordination of the violins' alternating pizzicatos at P. A final clincher: On my copies at least, the London pressing is the cleanest and quietest of the three. A.C.

DvoRAK: Concerto for Cello and Orchestra, in B flat, Op. 104. Lynn Harrell, cello; London Symphony Orchestra, James Levine, cond.

[Charles Gerhardt, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1155, $6.98. Tape: trli ARK 1-1155,

$7.95; REARS 1-1155, $7.95. Quadriphonic: ARD 1-1155 (Quadradisc), $7.98; ART 1 1155 (0-8 cartridge), $7.95.

Since the landmark mono recordings of the Dvorak 13 flat Concerto-in the Thirties the taut, imperious Casals/Szell (Seraphim 60240), a well-nigh definitive account; in the Fifties the richer, more flexible Rostropovich/Talich (last available on Parliament)- there have been numerous distinguished accounts: the introspective Starker/Susskind (Angel S 35417), the muscular yet plastic Starker/Dorati (Mercury SRI 75045), the crisp if somewhat offhand Fournier/Szell (DG 138 755), the solid middle-of-the-road Gendron/Haitink (Philips 802 892), the lyrical Tortelier/Sargent (in England, HMV SXLP 30018), and the colorful and freshly idiomatic Chuchro/ Waldhans (Supraphon SUAST 50667). And yet here is a recording more illuminating, eloquent. and exciting than any of the others.

Lynn Harrell is a remarkably secure and perceptive technician and musician, yet in this performance he and James Levine have integrated the solo cello spatially and emotionally into the whole ensemble. Instead of challenging the orchestra, Harrell constantly forms ad hoc concertino groupings with its soloists. Levine has examined the score closely, both in its detail and in its over-all contours. I have rarely heard the first movement hold together so well with so clear a differentiation between the basic allegro and the slower tempo for the secondary thematic material. In the remaining movements he occasionally anticipates ritards slightly, but that is more than offset by his scrupulous execution of countless other tempo modifications.

Many of Levine's orchestral revelations depend on precision of instrumental execution, which often produces a sense of hearing the music for the first time. The London Symphony is in its very top form, and the recording is technically extraordinary. The album packaging is attractive; my pressing was first-rate. A.C.

In quad: There is more sheer majesty in this recording, perhaps, than in any four-channel disc I've heard. The orchestra really hangs together with no sense of electronic manipulation, though the large-scale orchestra-plus-audience treatment may suggest the proportions of, say, the Mahler orchestra more than those one is used to in Dvorak. The effect is, unfortunately, spoiled by the extremely gritty surfaces in the first movement on both copies I've tried.

R.L.

GAGLIANO: La Dafne. For an essay review, see page 84

HANDEL: Cantatas: Delirio amoroso; Nel dolce dell' oblio. Magda Kalmar, soprano; Liszt Chamber Orchestra, Frigyes Sandor, cond. [Andras Szekely, prod.] HUNGAROTON SLPX 11653, $6.98.

Neither of these cantatas is among Handel's great works in this genre, but they are both pleasant enough.

Delirio amoroso hardly lives up to its text. It is, rather, a bravura piece for coloratura soprano, concerted solo instruments, and small orchestra. The cantata--almost a testa in length--is indeed too long and repe titious, but it has a nice overture and a couple of fair arias. It would make a better impression somewhat pruned and without repeats. Nel dolce dell' oblio is one of the pastoral cantatas: light and close to the then prevailing intermezzo tone. This is a slight piece, but not without a certain charm, and the recorder, which enhances the pastoral tone, blends nicely with the voice.

Magda Kalmar has a bright and fresh voice that carries well; unfortunately she seems to be a little closely miked. This promising young artist takes the extensive vocal convolutions with ease, and she has temperament. What she still needs to learn is the fine art of coloring the voice. All the instrumental soloists are good and the little orchestra is competent, but conductor Sandor is a bit stodgy and scarcely differentiates between the pathetic and the pastoral. P.H.L.

HAYDN: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra: in G, H. XVIII:4; in D, H. XVIII:11. Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, piano; Zurich Chamber Orchestra, Edmond de Stoutz, cond. [David Mottley, prod.] ANGEL S 37136, $6.98.

This is a shocking record. The sound is coarse, loud, lumpy, and one-dimensional; the piano tone sounds as if the microphone has been placed in the innards of the instrument, while the orchestra gives the impression of the combined string body of the New York Philharmonic and the Boston Symphony.

Michelangeli goes through these pleasant rococo concertos with a ferocious and relentless banging. Perhaps the inept recording has something to do with his harshness, but Michelangeli fully matches the engineering with his musicianship. There is never a shade of flexibility or a bit of sensitive phrasing, never those delicate changes in tempo and dynamics that make the re turn of a rondo theme a joy or the onset of the recapitulation an event anticipated with excitement. In addition he consistently arpeggiates his chords and in general keeps his two hands in different time zones, a style of playing that went out with the square rigger. A most annoying habit of the Italian pianist is to keep his foot on the pedal until further notice; at the end of sections the evanescent reverberations create a Cathedrale engloutie effect as suitable for this style as lederhosen for a formal dinner.

Too bad, for these are nice compositions.

P.H.L. HAYDN: Concertos: for Violin. Harpsichord, and Strings, in F; for Two Flutes and Orchestra, in P. Jacques Manzone, violin; Francoise Petit, harpsichord; orchestra, Henri Claude Fantapie, cond. Jeanette Dwyer and Claude Legrand, flutes; Mozart Society Orchestra, Guido Bozzi, cond.' ORION ORS 75198, $6.98.

In the Esterhazy household Haydn was a composer, conductor, and producer, but he was not a virtuoso soloist, and for that reason his concertos are overshadowed by his symphonies. Unlike Mozart, he did not re quire a concerto literature for his personal use.

The concerto for violin and harpsichord dates from his early Esterhazy period, and one can imagine it as intended for the com poser to play with his concertmaster, the same artist for whom he wrote so many solos in the symphonies of these years. The original manuscript is lost, not an uncommon event for early Haydn, but this performance, from a modern scholarly text, has the proper note of authenticity.

The concerto for two flutes is an arrange ment, by either Haydn or a trusted aide, from the fifth of five concertos composed around 1786 for two lire organizzate, the lira organizzota being a somewhat un wieldy cross between a hurdy-gurdy and an organ that enjoyed a brief popularity in France and Italy. When Haydn wanted to play this work in England, he chose more conventional instruments, and since the original version isn't likely to be heard of ten we need not have any fears about accepting it in this second form.

Bernard Herrmann

in 1942 A welcome revival of his early symphony.

The performers, clearly better known in Europe than in the U.S.. are good and well recorded. They play in the best French tradition, with a degree of lightness, verve, and melodic sensitivity that gets to the heart of these scores. Neither concerto can be regarded as profound, but the work for flutes is a lot of fun, and the interplay of the two soloists in the earlier work reveals typical Haydnesque mastery of unusual forms.

R.C.M.

HAYDN: Trio for Flute, Cello, and Piano, H. XV:15-See Beethoven Quintet for Piano and Winds. Op. 16.

HERmaNN: Symphony. National Philharmonic Orchestra, Bernard Herrmann, cond. [Gavin Barrett, prod.] UNICORN RHS 331, $7.98 (distributed by HNH Distributors, Box 222, Evanston, III. 60204).

Bernard Herrmann's extraordinary 1941 symphony unfolds expansively in the form of a multi-contoured, moody, often bleak tonal landscape (Herrmann ranks with Sibelius. Barber, and Vaughan Williams among the greatest of musical landscape seascape artists), within which motivic fragments take form and disappear in unfathomable cycles. The composer establishes a symphonic momentum quite unlike the more immediate dynamism of his film music.

Especially attractive is Herrmann's structural use of instrumentation; repeated hearings increasingly reveal the subtlety of his contrasts within and among orchestral choirs. He will, for example, use near-cluster effects in the brasses to counteract the simplicity of a motive, sometimes juxtaposing several winds in very close harmonies, as in the hauntingly icy trio of the night marish scherzo. By the end of the finale, Herrmann has begun to superimpose ideas in almost Ivesian fashion--not surprising in view of his close ties, as a young conductor, with his great predecessor.

It is saddening that a work of this quality has remained virtually unknown for over thirty years, but there is some consolation in the delight of rediscovery. In this well engineered English recording, Herrmann leads the National Philharmonic in a glowing, subtle, and sonorous performance whose control and understatement invite the listener to participate especially deeply in the emotional fabric of the work.

R.S.B.

Hiller: Sonatas for Piano: No. 4; No. 5. Frina Arschanska Boldt and Kenwyn Boldt, piano. [Giveon Cornfield, prod.] ORicti ORS 75176, $6.98.

As heard in these two sonatas, the style of Lejaren Hiller (born in New York in 1924) is very deliberate--too deliberate for my taste.

The Fourth Sonata (1950) is supposed to be humorous, each movement based on a different pianistic style. Yet Hiller rarely manages to do anything really funny, whether in the late Romanticism of the first movement, the blues of the second, or the tarantella of the fourth. Only the third movement trio, with its herky-jerky mock seriousness, got a smile from me. Else where, parody or no, the music just sounds like plain-and-simple bad composing.

The Fifth Sonata (1961) has more serious pretensions and features one movement, the third of the four, written in an ultra quiet, space-filled style entirely in the piano's upper registers. But again everything seems to have been planned out abstractly, with little feeling of inevitability in the musical progression. While this can work in a more avant-garde style, in Hiller's more conservative idiom the paradoxical effect is the opposite of deliberation-rather like bad improvisation. Furthermore, the writing in both sonatas is long-winded; even good ideas are spoiled by overelaboration, as in the twelve-and-a-half-minute-long third movement of the Fifth Sonata.

Kenwyn Boldt seems to have reasonable command of the Fifth Sonata. Frina Arschanska Boldt admittedly has somewhat inferior material to work with in the Fourth, but some of her playing, especially in the finale, sounds amateurish. Perhaps, however, there was nothing else to do with the movement, and the badly tuned piano is no help. R.S.B.

MOZART: Cosi fan tutte, Fiordiligi Dorabella Ferrando Guglielmo Despina Don Alfonso K. 588.

Gondola Janowitz (s)

Brigitte Fassbaender (ms)

Peter Schreier (t)

Hermann Prey (b)

Ren Grist (s)

Rolando Panerai (b)

Vienna State Opera Chorus; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Karl Bohm, cond. [Werner Mayer, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709059, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence) [recorded live at the 1974 Salzburg Festival].

While this set-taped at a live Salzburg performance on Karl Bohm's eightieth birth day. August 28, 1974-adds little to the Cosi discography, it gave me much pleasure, thanks principally to the Fiordiligi and the over-all flavor of the performance.

Even those not partial to Gundula Janowitz will have to credit her courage in tack ling so fearsome a part as Fiordiligi in a live recording. In fact, there are only a few mi nor points that might have been smoothed out in the studio; as vocalism this ranks with the best of the extraordinary Fiordiligis on record. Granted she tends, particularly when singing in Italian, to under articulate words often to the point of near vocalise; for me the emotions are so vividly communicated by modulation of her hauntingly pure timbre and by sensitive phrasing that I can't object.

Since Cosi depends so heavily on right ness of proportion, both internal and over all, live-performance recording might not seem particularly advantageous-or even desirable. But in this case there is an un mistakable gain in continuity and theatrical presence, and Bohm secures a level of orchestral execution and vocal balance that would easily pass muster in the studio. He does not seek crisp accents, but there is a wonderful sense of flow missing from his similarly slowish 1963 Angel recording; in that respect the 1974 performance is closer in spirit to his 1955 Vienna recording (now on Richmond). Of signal importance is the superb engineering: The voices are well to the fore, though not excessively so, with an individual clarity matched only by the Davis/Philips set.

Against these virtues stand two serious flaws. First, the cuts. Just to hit the high points: in Act I, a chunk of the "Sento, o Dio" quintet, some of the military music, the Ferrando/Guglielmo duet "Al fato clan lep,ge" (a "standard" cut, but a bad one), and chunks in the finale: in Act II, a stanza of Despina's "Una donna a quindici anni," Ferrando's "Ah! loveggio" (another "standard" cut, but more defensible if you don't have a tenor who can sing it) and also his "Tradito, schernito," Dorabella's "E amor un ladroncello," half of the middle section of the Fiordiligi/Ferrando duet "Fragli am plessi," and chunks in the finale. These cuts are of course outrageous, live performance or no, and one can only marvel at the chutz pah of Gunther Rennert, director of the Salzburg production, when he writes in his booklet essay: "The sole criterion for the solution of all questions of interpretation is the score, whose authority is binding on both conductor and producer, and within which the very substance of the work is rooted. Style and interpretation are dependent on it." For a man who loves Cosi as much as Bohm purports to, he was awfully acquiescent in this butchery; but then his first Cosi recording used a rather similar "edition." Still, now that we have three note--complete versions readily accessible (Leinsdorf/RCA, Solti/London. Davis/Philips), the Salzburg set can be considered for its value as a supplementary version. And some of the cuts have a silver lining, for they minimize the impact of the other serious defect: Peter Schreier's screechy Ferrando. He has previously recorded the role quite decently, and he did a lovely "Un aura amorosa" and "Tradito, schernito" on a London Mozart-aria disc: in fairness to a fine singer, this outing can be safely over looked.

Most of the remaining singers register in the plus column. Brigitte Fassbaender has a darker tone than most Dorabellas. and she makes some nice character points. Reri Grist's one tone color is fortunately well adapted to Despina, and she's better than most of the rather sorry competition. Hermann Prey repeats his admirable Guglielmo from the Jochum/DG set and does his best to keep Rennert's camped-up staging out of his singing.

On the debit side is the Alfonso of Rolando Panerai, who already has an excel lent recorded Guglielmo to his credit (the old Karajan set). His warm baritone should suit Alfonso well, but his vocal production is so erratic that a live performance is apt to give us too generous a portion of flat, hol low crooning, which is the case here. I'd still like to hear what he could do in the studio. The Vienna State Opera Chorus sounds quite ghastly in its mercifully brief contributions.

In addition to the complete sets (among which my choice remains the Solti), there are several others that have more to say about Cosi than this one. I would call particular attention to the Jochum/DG, a per formance of special coherence that may not survive in the catalogue much longer with the arrival of the newcomer. K.F. 1E31

MOZART: Quartets for Flute and Strings: in D, K. 285; in G, K. 285a: in (96) C, K. 285b; in A, K. 298. Michel Debost. flute: Trio a Cordes Francais. SERAPHIM S 60246 $3.98.

Comparison: Rampal, Stern, Schneider, Rose Col. M 30233 On the way to Paris in 1778, Mozart paused in Mannheim, hoping to get a job (he didn't) or a wife (she jilted him). Instead he met a ripoff artist, a Dutch flutist named De Jean, who knew genius when he saw it, commissioned chamber music and concertos for his instrument, and welshed on his debts. It was all the more depressing since Mozart was not at all fond of the flute, found it tedious to compose so much for it so quickly, and moreover needed the money not only to pay bills, but to prove to his papa back in Salzburg that he was not largely wasting his time (which, in the last analysis, he was). From this episode come the three K. 285 quartets, uneven works for the mature young Mozart and perhaps with a fake movement or two added by a less skilled hand. K. 298 dates from Paris a few months later, when his fortunes really came to low ebb.

As is often the case with Mozart, great as his trial may have been, the music is light, lyric, and sparkling and conveys a sense of joy. These flute quartets are among his most popular early chamber works and are amply represented in the current catalogue, with the Columbia edition of Jean-Pierre Rampal, Isaac Stern, Alexander Schneider, and Leonard Rose probably dominant. If you have that on your shelves, you're in fine shape. If you're shopping for the music, consider the current Seraphim, which is first-class in style and performance, equally well recorded, and three dollars cheaper.

Like Mozart, I find all of this too much for one sitting. Taken one quartet at a time, it is charming indeed, entertainment music at its most refined. And, although the Rampal performances are somewhat brisker and more animated, Debost's lyric playing is a pleasure to hear. You can't lose. R.C.M.

MOZART: Quintet for Clarinet and Strings, in A, K. 581''; Quartet for Oboe and Strings, in F, K. 370'. George Pieterson, clarinet; Pierre Pierlot, oboe`; Arthur Grumiaux and Koji Toyoda, violins; Max Lesueur, viola; Janos Scholz, cello. PHILIPS 6500 924, $7.98.

Tape: NM 7300 414, $7.95.

Both of these masterpieces receive distinguished performances on this well-recorded disc.

The young Dutch clarinetist George Pieterson plays with a coolly linear sound. He can be tangy and robust when required, and I like his straightforward phrasing very much. His performance of the sublime clarinet quintet is ideally matched to the work of the Grumiaux-led string ensemble, which similarly pays heed to the crisp articulation and the purity and niceties of classical style. The Larghetto is perhaps too straitlaced for full effect, and in both of the third-movement trios I question the practice of pausing slightly and then proceeding at a tempo slower than that of the menuetto proper. The last-movement variations, however, are airborne here, and ...

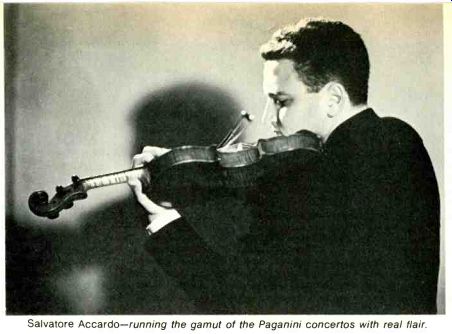

-----Salvatore Accardo-running the gamut of the

Paganini concertos with real flair..

... surely no other team has better integrated the adagio fifth variation. A superb reading, then, even if it doesn't, except in the last movement, dislodge the Deplus/Danish Quartet version (in Telefunken 56.35017, December 1974). The oboe quartet receives one of its great recorded performances. Pierre Pierlot's phrasing, like that of his string colleagues, is full of excitement and enlivening impulse, and his breath control and digital facility are justly celebrated (though I would prefer less vibrato). H.G.

PAGANINI: Concertos for Violin and Orchestra (6). Salvatore Accardo, violin; London Philharmonic Orchestra, Charles Dutoit, cond. [Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2740 121, $34.90 (five discs, manual sequence).

Concertos: No. 1, in D. Op. 6; No. 2, in B minor, Op. 7; No. 3, in E (ed. Szeryng); No. 4, in D minor (ed. Szeryng); No. 5, in A minor (ed. Mompellio); No. 6. in E minor (ed. Mompellio) [from DG 2530 467, 19741.

Comparisons: Ashkenase, Esser (Nos. 1, 2) Friedman. Hendi (No. 1) Grumiaux, Bellugi (Nos. 1, 4) Perlman, Foster (No. 1) Rabin, Goossens (No. 1) Tretyakov. Yarvy (No. 1) Szeryng. Gibson (No. 3) Bellugi (No. 4) DG 139 424 Victr. VICS 1647 Phi. 6500 411 Ang. S 36836 Sera. S 60222 Mel. iAng. SR 40015 Phi. 6500 175 Col. M 30574

It was only a matter of time before one of the world's more intrepid virtuosos decided to run the gamut of the six Paganini violin concertos that are now (one way or an other) extant and to produce a complete set.

In a sense, Salvatore Accardo seemed des tined to take up the challenge, since he was the first player to win first prize in the Paganini Competition, in 1958, and often plays, we are told, on Paganini's own Guarneri del Gesa. His release in 1974 of the reconstructed Concerto No. 6 bode well for this undertaking, and now it has come to fruition with resounding success.

It is true, I suppose, that if you can play one Paganini concerto you can play them all. It is not quite true that if you have heard one of them you have heard them all, for No. 1 is much more interesting than the sequence-riddled No. 5, for example, and the famous "Campanella" finale of No. 2 is one of the most attractive movements in the en tire set. In the main, listening to five discs of Paganini consecutively--even with time out for eating, sleeping, and honest wage-earning-produces eventual paralysis, both emotional and lumbar, and is not to be recommended. Only so many passages of tenths, so many harmonics, so many flying bow strokes, so many left-hand pizzes can be absorbed with anything like strict attention, and even Paganini's sweet slow melodies begin to sound perfunctory. Still, it is a worthwhile venture to get all the concertos into one box, and Accardo has done it with real flair.

A word about the origins of the more obscure concertos. No. 3, as fiddle fanciers will remember, was obtained by Henryk Szeryng from Paganini's heirs several years ago and was introduced by him in concert and on disc. His edition is used here. No. 4 was revived in Paris in 1954 (Accardo plays a Szeryng edition also). No. 5 existed in a transcription for violin and piano and was reconstructed by Federico Mompellio, an Italian musicologist, and introduced in Vienna in 1959; it has not been previously recorded, as far as I know. No. 6 was found in a London antique shop in 1972 in a violin/guitar version; it was orchestrated by Mompellio and introduced by Accardo a year and a half ago. (I reviewed the recording in October 1974.) Mompellio did his job well: The orchestrations are full of vitality and give due attention to woodwind coloring and brass pronunciamentos. As for cadenzas, Accardo has written his own for four of the concertos and revised Emile Sauret's for No. 1 and Remy Principe's for No. 5. He stops at nothing, providing a miniature Caprice on each occasion. Coming as these cadenzas do on top of twenty minutes or so of acrobatic virtuosity, they seem al most de trop; the cadenza for No. 4, for in stance, is nearly four minutes long. But it is Accardo's show, and one can't blame him for making the most of it.

Accardo has made these works his property, and this integral set will surely stand as a landmark of sorts for a long time to come. His tone is brilliant, his temperament bold, his technique superb. This is not to say that some competing versions of individual concertos are not of equal accomplishment or do not offer attractive view-points slightly at variance with his. In No. 1, for instance, Grumiaux's marvelous recording is a bit more precisely defined rhythmically and more cohesive and elegant in its surface shaping. Perlman is a more dazzling technician-somewhat more articulate in fast passages-and moves along with less emoting in the lyric moments, all to the good. Friedman runs very close to Accardo in approach and in tonal brilliance. Rabin's version remains winning but is at a lower emotional pitch. Ashkenase and Tretyakov are cast into the shade by comparison.

In No. 3, Accardo is more extroverted and aggressive than Szeryng, who emerges with a lower profile-less tightly rhythmic in the fast movements, and less nuanced (though still lovely) in the Adagio, altogether a "softer" performance throughout.

In No. 4, Grumiaux again is beautifully musical and mellower in tone; Ricci is less coherent in the first movement, sings nicely in the second, but misses the pulse of the finale.

The London Philharmonic handles its share of the proceedings in a spirit that matches Accardo's. Those long introductory tuttis, with their big chordal exclamations and general air of storm and bustle, are played to the hilt. Rhythm is always alert, and details of orchestration are given their fair share of attention. A Paganini soloist could not ask for more.

He could, however, ask for more in the way of program annotations: DC's booklet offers some roadblocks. An essay on "The Social History of Virtuosity" is printed in German and French, and one on "Paganini and His Six Concertos" in English and Italian. The latter piece is addlepated to start with, and the translation into English renders such sentences as this (referring to the D major Concerto): " It bears the number, Opus 6 because it was published by his son Achille in 1851 through Schonenberg and Schott, the first in Paris and the second at Mainz, ending with No. 5 the series of com positions printed during Paganini's life by Ricordi in Milan, the only works having a number, while others had been printed in unauthorized editions." Got it?

S.F.

Alexander Nevsky, Op. 78. Betty Allen, mezzo-soprano; Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia; Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, cond. [Jay David Saks, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1151, $6.98.

Tape: 1101 ARK 1-1151, $7.95; ARS 1 1151, $7.95. Quadriphonic: ARD 1-1151 (Quadradisc), $7.98; ART 1-1151 (0-8 cartridge), $7.95.

Comparison: Alexandroy Pro Musics Orch. Turn. TV-SU M

As in his pioneering Forties recording for Columbia, Ormandy still conducts Nevsky with technical aplomb and seamless assurance. The breadth and heroism of the epic unfold in a natural way, with no ponderous italicization and no hysteria. If the Mendelssohn Club will hardly be mistaken for the Red Army or Bolshoi chorus, it is at least solidly professional, free of obtrusive "American collegiate" choral mannerisms.

Betty Allen is vigorously competent, though not in a class with Ormandy's previous soloist, the then-in-her-prime Jennie Tourel.

The ultimate Nevsky remains to be re corded. Reiner (RCA, deleted, unfortunately sung in English) caught best the music's snarling and brooding menace. Previn (Angel S 36843) offers splendid execution and vivid recording, but his approach is too civilized for me. Schippers (Odyssey Y 31014) has Lili Chookasian's darkly eloquent singing of the "Field of the Dead." The real sleeper is the recent Turnabout re lease, which even has a filler--a respectable Love for Three Oranges Suite conducted by Froment. The Nevsky performers are identified only as "Pro Musica Orchestra and Chorus, conducted by G. Alexandrov." The performance seems to be from an actual concert by a genuine (and extraordinarly vital) Russian chorus, with an orchestra that is adequate enough, some nervous brass playing excepted. The mystery mezzo really knows what her song is all about, even if she can't float a smooth legato line in the manner of the younger Tourel or of Chookasian. Alexandrov reads the score with incomparably invigorating energy and plasticity.

Sonically, the new Ormandy Nevsky falls between the edgy, over-miked Rach maninoff Second Symphony (December 1975) and the smooth, suave Shostakovich Fifth (January 1976). The violins are bright, as is the extremely detailed percussion, but not strident or glossy. The various instrumental and vocal forces are vividly captured and well-balanced. A.G.

In quad: I become increasingly disturbed by the slightly acid, slightly grainy sound that seems to plague the Philadelphians on Quadradiscs. The velvet in RCA's London Symphony recording of the Dvorak Cello Concerto reviewed this month proves that the harshness given the Philadelphians is not an inherent by-product of Quadradiscs.

Yet there it is, compounded by a miscellany of extraneous surface noises at some parts of my review copy.

This is a shame-the effect is otherwise superb. Being encircled by orchestra and chorus really works, with the antiphonal exchanges of the battle music and some of the choral passages adding much to the excitement and vividness of what is, after all, descriptive music. It does not add to the sense of one's being in the presence of a real orchestra in a real hall (a quality that the Dvorak, for example, achieves magnificently). Rather, the listener is con fronted with an arbitrary deployment of musicians placed and recorded in the studio so as to achieve specific musical, dramatic, and sonic ends. R.L.

Reger: Quintet for Clarinet and Strings, in A, Op. 146. Karl Leister, clarinet; Doric Quartet. [Ellen Hickmann, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 303, $7.98.

Not long before his death in 1916, Max Reger wrote a clarinet quintet that he obviously intended to take its place alongside those of Mozart and Brahms. Reger was not, even by the most tolerant standards, a modest man, and in his time his ego was nourished by a coterie of critics who saw in him the logical heir of Beethoven and Brahms. He still commands considerable respect in Germany, though his music seems by now to resist export to other countries.

Though there might be other responses to the combination of clarinet and strings. Reger, like Mozart and Brahms, is inspired to a rather elegiac mood. His quintet differs from his masters' in its greater contrapuntal emphasis, blending the wind instrument more into the string body. In his first movement, Reger expands conventional sonata form by adding to the exposition a third subject with its own key; this theme later figures prominently in the slow third movement. In the second movement, his scherzo seems to have as much trouble getting off the ground as Brahms's similar movements often have, and I find the slow movement lacking in strong inspiration. The finale, a long theme and variations, is possibly the strongest section musically; perhaps Reger was most comfortable spinning out variations on his own or others' themes.

The only alternative to the new DG recording by Karl Leister and the Droic Quartet is that by the Bell'Arte Ensemble in one of the Vox Boxes devoted to Reger's chamber music. I have not heard that performance, but this one is very good: It takes this kind of solid German playing to bring clarity to Reger's often involuted textures. I should also note that this performance, though spread over two sides, runs only 33:42. P.H.

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV: Scheherazade, Op. 35. Sidney Harth, violin; Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Zubin Mehta, cond. [Christopher Raeburn, prod.] LONDON CS 6950. $6.98.

Comparisons: Haitink / London Phil. Phi. 6500 410 Rostropovich /Orch. de Paris Ang. S 37061

The latest warhorse to come out of the gate wearing the Mehta/Los Angeles/ London colors well may be another favorite of the fans who earlier put their money on the same stable's Strauss Zarathustra (1969), Saint-Saens Organ Symphony (1971). Holst Planets (1973), and last September's "Virtuoso Overtures." But on my card this Scheherazade is insuperably handicapped by an overweight and excessively mannered jockey. Mehta's drearily stodgy third movement is even slower, yet less flowing, than Rostropovich's, while both his first and fourth movements are heavily labored.

The Los Angelos play well and are powerfully recorded, as always, yet the Rostropovich/Parisian version is far more dramatically vivid except for the London engineers' magnificent gong roar in the finale's shipwreck climax.

Over-all, for more transparent yet glowingly warm sonics as well as for the most grippingly magisterial reading to date, the 1974 Haitink/Philips version remains un challenged. For that matter, both the distinctively individual versions by Beecham (Angel S 35505) and Ansermet (London CS 6212) remain incomparable despite their 1958 and 1961 technologies. R.D.D.

Rouen: Overtures. Academy of St. Martin in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner, cond. PHILIPS 6500 878, $7.98. Tape: 1101 7300 368, $7.95.

Il Barbiere di Siviglia; L'Italiana in Algal; La CambiaW di matrimonio; La Scala di seta; Tancre a Il Signor Bruschino; Il Turco in Italia; L'Inganno WIC.

This record simply obliterates the competition. Thanks to the chamber-orchestra sized string section and the quality of execution, every wind line in these works emerges with the full import Rossini clearly intended, and for that matter the vividly re corded strings are as full and precise as any I've heard in this music. Listen to the opening string pizzicatos of L'Italiana in Algeri, crisp yet bursting with color, followed by the bold, melting oboe solo; then all you'll need to know is that every bar in these eight overtures maintains that standard. Marriner's pacing is unerringly just, and the orchestral realization (the dazzling wind soloists might deservedly have been identified) makes everything else on records-except the overture in Silvio Varviso's complete Barbiere (London OSA 1381), which also uses reduced strings-sound like a generalized run through.

In Marriner's hands, the two little-heard overtures here, La Cambiale di matrimonio and L'Inganno felice, have quickly become favorites of mine. The former in particular is a zestful romp every bit the equal of Sig nor Bruschino, and I share Geoffrey Crankshaw's incredulity (in his fine liner notes) that so mature a piece could have been written by a student. The absence here of such staples as Cenerentola. Gazza ladra, and the bigger pieces-Tell. Semiramide, and Siege of Corinth-strongly suggests the imminence of a sequel. The sooner the better. K.F.

SAINT-SAENS: Symphony No. 3, in C minor, Op. 78 ( Organ). Bernard Gavoty, organ; Orchestre National de l'ORTF, Jean Martinon, cond. [Rend Challan, prod.] ANGEL S 37122, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

Tape: EP 4XS 37122, $7.98; 8 XS 37122, $7.98.

Comparison: Zamkochian. Munch /Boston Sym. RCA LSC 2341 Wait just a minute!

This is definitely not just another sonic spectacular or just an other Saint-Saens Organ Symphony show piece performance.

It's exceptional, first, in that it represents the completion of the first integral recording of the five existing Saint-Saens sym phonies, by Martinon and the Orchestre National--Nos. 1 and 2 on Angel S 36995 (July 1974), the early unnumbered sym phonies in A and F on S 37089 (August 1975). It is more rewardingly exceptional, how ever, in that it is triply distinctive in interpretation, execution, and recording--an accomplishment achieved hitherto only by the long-reigning, generally preferred.

grandly expansive 1960 Munch version for RCA and to a far lesser degree by the smaller-scaled but poetically lyrical 1963 Ansermet version for London (currently available in a Stereo Treasury reissue, STS 15154). Now Mart ion. undoubtedly benefiting from his experience of having re corded the Organ Symphony earlier (with the same orchestra but a different organist, Marie-Claire Alain) in 1971 for Erato/Musical Heritage Society, gives us the most fiercely virile and dramatic reading I know, making the recent one by Ormandy for RCA (ARL 1-0484) sound almost pablum bland in comparison. Both the orchestral sound and the sound of Gavoty's appropriately "symphonic" organ of the Eg lise Saint-Louis des Invalides are the most quintessentially "French" of any version to date. And the Pattie audio engineering is an outstanding triumph of power, bite, and solidity achieved without sonic blurring even in the long reverberant period of the cathedral locale.

To be sure, the close, ultra-vivid realism, to say nothing of the muscular strength, of this treatment may not be to every listener's taste. And for all the dramatic excitement, there is no direct challenge to the grandeur, sonic warmth, and well-nigh magical atmosphere of the forever unique Munch version. But Martinon's Saint-Saens is unique as well. It also is outstanding technologically in a highly individual way, even when played back in stereo only. R.D.D.

SCHUBERT: Quartets for Strings: No. 12, in C minor, D. 703 (Quartettsatz): No. 14, in D minor, D. 810 ( Death and the Maiden). Melos Quartet. [Rudolf Werner, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 533, $7.98. Comparison Collegium Aureum 01 BASF KHC 22959

Last November, I welcomed the Collegium Aureum Death and the Maiden as a good middle-of-the-road performance, steering a path between the generally mellow approaches of many European ensembles and the generally high-gear, high-polish attitude of many American groups. The Melos Quartet is in the middle of the same road, but to less consistently good effect.

There is nothing whatever wrong with this performance, but in the first two movements one is aware of chances missed, of explorations not taken-mainly in the matter of bringing out inner, answering voices, for the emphasis here is on the top line. And while the Melos obviously aims at a lyric shaping of the Allegro and avoids a tight pouncing on the dotted-eighth-note figure, the final result is just a little bit stolid. (The Melos does not, incidentally, take the exposition repeat; the Collegium Aureum does.) Another chance missed, I thought, was in the third variation of the second movement, where the three-part cello chords can simply lift you out of your seat if they are played with muscle. They are all too docile here. The last two movements go very well, however, with the Presto crisper and more sharply defined than that of the Collegium Aureum.

The Quartettsatz stands up to the com petition-that of the Guarneri (RCA LSC 3285), for instance, though the Melos is slightly more relaxed and more broadly conceived. The players don't miss the chance to shape the dynamics with flexibility, and that is half the battle. S.F.

SCHUBERT: Quintet for Strings, in C, D. 956. Guarneri Quartet; Leonard Rose, cello. [Peter Dellheim, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1 1154, $6.98.

Comparisons: Juilllard Ot. Greenhouse Col. M 32898 TátraiQt,Szilvósy Hung. LPX 11611 Taneyev Ot, Rostropovich West. WGS 8299

For all the performance problems Schubert poses to ensembles, he seems to bring out the best in them. How else to explain the fact that the Guarneri here offers the fourth strong version of the C major Quintet in the past year and a half? In September 1974, I dealt with the Juilliard and Tatrai editions, quite different from each other, and each with much to say for itself. Make way now for the Guarneri, which runs side by side with the Juilliard in terms of finesse, sensitivity, and attention to detail. The Tatrai, an impressive performance, has more rugged contours, less smooth ensemble, some times more sonority. It is Schubert in country clothes, if you will, and in this resembles the Rostropovich/Taneyev version, reviewed in June 1975, which strides into the music with a healthy directness and without worrying too much about subtleties.

The Guarneri has always made a specialty of knowing what to look for below the top line in a score, and that sense of acute adjustment and balance prevails here. A special depth is given to the development section of the first movement, for example, and to the second subject of the finale, where the second-violin and viola parts underneath those first-violin triplets are given a chance to make their point, rather than being subdued to background status, as is often the case.

The Guarneri's first two movements here give a general impression of chasteness: the readings are mellow and refined, due in part to the translucent sweetness of first violin ist Arnold Steinhardt's tone-less biting and muscular than Robert Mann's in the Juilliard version. In the last two movements the gloves come off; there is plenty of grit and a healthy swing to the scherzo, and in the finale all five players bite into the sforzandos with a vengeance. In such company as this, both the Tatrai and the Amadeus versions recede somewhat into the back ground. The Guarneri and the Juilliard, along with the quite different Taneyev, set a beautifully high standard. S.F.

Schubert Sonata for Piano, in D, D. 850; German Dances (16), D. 783. Alfred Brendel, piano. PHILIPS 6500 763, $7.98.

This is one of the more successful discs in Brendel's Schubert series.