reviewed by

ROYAL S. BROWN ABRAM CHIPMAN R. D. DARRELL PETER G. DAVIS SHIRLEY FLEMING ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE CLIFFORD F. GILMORE HARRIS GOLDSMITH DAVID HAMILTON DALE S. HARRIS PHILIP HART PAUL HENRY LANG ROBERT LON( ROBERT C. MARSH ROBERT P. MORGAN CONRAD L. OSBORNE ANDREW PORTER H. C. ROBBINS LANDON J OHN ROCKWELL HAROLD A. RODGERS PATRICK J . SMITH SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

---- The Vegh Quartet-impeccable and revelatory Beethoven.

BACH: Brandenburg Concertos (6), S. 1046-51. English Chamber Orchestra. Johannes Somary, cond [Seymour Solomon, prod.] VANGUARD VSD 71208 , 9. $13.96 (two discs). Quadriphonic: VSO 30049/50, $15.96 (two SQ-encoded discs).

Much of Johannes Somary's recorded work has left me with a feeling of cool respect: it has taken his Bach finally to turn me on.

Last year's B minor Mass (Vanguard VSD 71190/2, March 1975) had not only disci plined and clear-textured choral work (not unknown in his Handel oratorios), but also original and cogent ideas about tempos and ornamentation. In the Brandenburg’s, there are fewer surprises but a dominant vigor, well-built expressive line (within what is acceptable in a modern framework), and alert and confident execution.

In No. 1, brisk tempos are the rule, even for the Menuet-an idea that may have orig inated on records with Boyd Neel, though Somary misses Neel's rollicking treatment of the Polonaise. Like so many conductors,

-----------------

Explanation of symbols

Classical:

- Budget

- Historical

- Reissue

Recorded tape:

- Open Reel

- 8-Track Cartridge

- Cassette

-----------------

Somary understates the poignant tragedy inherent in the Adagio, a movement I con fess preferring to hear in the "anachronistic" style of Casals (especially in his earlier, long-deleted Prades set). Carl Pini here plays a genuine violino piccolo, and the rendition includes apt embellishments. No. 2 is moderately lively throughout, with a se cure, if not roof-raising, performance of the clarino trumpet part by John Wilbraham.

Somary's solution to the phantom middle-movement problem of No. 3 is a brief harpsichord cadenza from Harold Lester. The rhythmic and dynamic characterization of the two outer movements is excellent, with superb clarity and stereo separation of the respective trios of violins, violas, and cellos. David Munrow and John Turner are the recorder soloists in No. 4.

Unless you're heretical enough to want flutes in this work (I do), there's nothing to complain of here.

In No. 5, Lester's harpsichord cadenza is delivered with real ferocity, and the ensuing tutti attack will jolt you right out of your chair. Also notable in the first movement is the smooth blend of flute and violin.

The slow movement includes an expressive cello reinforcement of the lower keyboard voice, which I have not encountered often.

No. 6 is not memorably expressive, but Somary has chosen his instrumentation wisely: Gambas are used instead of cellos to help differentiate the lower "concertino" voices from the continuo, which here substitutes a wiolone for double bass.

Somary provides good liner notes, and the engineering' is warmer and mellower than usually provided him. While nobody could ever declare one set of the Brandenburg’s the best for all time and tastes, the new one adds a serious contender to the elite group. It is less than a year since Van guard issued the Davison/Virtuosi of Eng land set, on Everyman (SRV 313/4 SD, September 1975), and that is a hard act to follow. That Somary's account is no anticli max speaks volumes of praise.

A.C.

BEETHOVEN: Quartets (6), Op. 18. Vegh Quartet. TELEFUNKEN 36.3504 2, $20.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Quartets, Op. 18: No. 1, in F; No. 2, in G: No. 3. in D. No 4. in C minor: No 5, in A No 6. in B flat

BEETHOVEN: Quartets (3), Op. 59. Ouartetto Italian. P HILIPS 6747 139, $15.96 (two discs, manual sequence). Quartets, Op. 59: No. 1, in F; No. 2, in E minor; No. 3. in C.

With Op. 18, the Vegh Quartet completes its second recorded Beethoven cycle, and one senses here a subtle shift in its interpretive values. The group's wisdom and deep involvement were unmistakable in their set of the middle quartets (Telefunken 36.35041, September 1974), but they were accompanied by a certain deliberation.

---------------------

Critic's Choice

The best classical records reviewed in recent months:

ADAM: Cello Concerto.

BARBER: Die Natali. LOUISVILLE LS 745, Dec.

BACH: Sonatas and Patinas. Milstein. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 047 (3), Jan.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 7. Casals. COLUMBIA M 33788, Feb.

BERLIOZ Symphonie fantastique. Karajan. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 597, Feb.

CHERUBINI: Requiem in D minor. Muti. ANGEL S 37096, Dec.

CHOPIN: Waltzes. Ciccolini. SERAPHIM S 60252, Jan.

DALLAPICCOLA: II Prigioniero. Dorati. LONDON OSA 1166, Jan.

Dvorak: Cello Concerto. Harrell, Levine. RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1155, Feb.

Dvorak: Symphony No. 7. Neumann. VANGUARD/SUPRAPHON 7. Jan.

GAGLIANO: La Dafne. Musica Pacifica. COMMAND COMS 9004-2 (2), Feb.

HERRMANN: Symphony. Herrmann. UNICORN RHS 331, Feb.

PENDERECKI: Magnificat. Penderecki. ANGELS 37141, Jan.

Rossini: Overtures. Marriner. PHILIPS 6500 878, Feb.

SCHUBERT: Quintet in C. Guarneri Quartet, Rose. RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1154, Feb.

SCHUBERT, SCFIUNIANN: Songs. Ameling. P rams 6500 706, Dec.

Schumann: Songs. Fischer-Dieskau. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 543, Dec.

Sibelius: Symphonies Nos. 5, 7. Davis. PHILIPS 6500 959, Dec.

TIPPETT: A Child of Our Time. Davis. PHILIPS 6500 985, Feb.

WEBER: Euryanthe. Janowski. ANGEL SDL 3764 (4), Feb.

WORK: Songs of the Civil War Era. Morris, Jackson, Bolcom. NONESUCH H 7131 7, Feb.

Boston Musica VIVA: 20th-Century Chamber Works. DELOS DEL 25405 and 25406. Jan.

---------------------

Even there, however, there were exceptions-for instance, the fast-paced finale of Op. 59, No. 2-and in Op. 18 the Vegh seems to have gained momentum. These performances of Beethoven's most virtuosic quartets are not only technically impeccable, but interpretively revelatory as well-in deed, quite the best segment of an altogether distinguished series. (The late quartets, for the record, are on Telefunken 46.35040, August 1975.) From the opening phrase of Op. 18, No. 3 (the Vegh follows the conjectured order of composition rather than the published sequence), one hears these sublime and inventive works interpreted as "Beethoven" rather than "early Beethoven." In place of the customary, and certainly appropriate sense of wide-eyed, youthful wonderment.

the Vegh strives for a grander emotional scale. In the second and fourth measures of the scherzo of Op. 18, No. 1. the cello's eighth notes are stressed in such a way as to point up that movement's uncanny-and for me previously unsuspected-resemblance to the second movement of Op. 130. The thematic resemblance between the opening of Op. 18. No. 2, and the second scherzo of Op. 131 is intensified by the Vegh's treatment. The tough, organic. yet highly expressive third movement of Op. 18, No. 5, anticipates the variation movements of Opp. 127 and 131 (not to mention those of the Opp. 109 and 111 Piano Sonatas). Such details-and countless others in all six performances-are subtly pointed and, however unusual, always in the con text of uncommon attentiveness to the letter of the score.

The Budapest Quartet took a similarly ripe view in its stereo Op. 18, but the result verged on italicized over-inflection and lacked brio, notably in the heavy opening movements of Nos. 5 and 6. The Budapest's more straightforward 1951 set remains preferable. The Vegh, by contrast, always delights with sprightly, well-scanned rhythm. My only half-quibble is with the finale of No. 1; it is brilliantly headlong and well-articulated, but the idiosyncratic structural pointing is a trifle arbitrary. I un hesitatingly call the Vegh's accomplishment the best Op. 18 we have had, and Op. 18 has always been uncommonly well treated on records, with excellent sets currently available from the Budapest (the 1951 performances, Odyssey 32 36 0023), the Hungarian (Seraphim SIC 6005), the Juilliard (Columbia M3 30084), and the Bartok (Hungaroton SLPX 11423/5). With the release of the three "Rasumovsky" quartets, the Quartetto Italiano's Philips cycle lacks only Op. 18, Nos. 2 and 4. The Italiano's Op. 59 is analogous to Claudio Arrau's well-known approach to many of Beethoven's piano sonatas: rich in tone; rather broad; lyrically, and often rhetorically, inflected.

Though the broadly paced opening movement of Op. 59, No. 1, has a bit too much exaggeration of detail for my taste, the scherzo is beautifully sprung rhythmically and clear as a bell texturally. The rich Adagio is eloquently songful, and the "Russian theme" finale, while on the sedate side, is convincingly dancelike. In the quasi-cadenza that leads to the finale, the first violin is rather spread in tone and overly careful in its phrasing.

The Italiano's performance of Op. 59, No. 2, does not seem to me ideally appropriate to this very different work, with its pistol shot opening and Eroica-like terseness.

Right at the outset, the quartet lets the air out of the sails with ritardandos on the sixteenth-note figurations of bars 4 and 7 that nullify the breathless impact of the silent bars 5 and 8. At several points in this movement the Italian does work up to the requisite speed and tautness, only to dissipate the admirably accumulating momentum with a rhetorical effect. The Molto adagio second movement is expressive, but again a bit soft and bland; rhythmic details tend to be generalized and smoothed away.

Though the Allegretto is not slow, the rhythm is on the slack side, especially in the trio. The Presto finale goes at a good clip and is helped by the strong presence of the lower voices, but it comes too late to save the performance.

Op. 59, No. 3, is admirable in every way a reading full of thrust and impact. The tempos are middle-of-the-road (no attempt to rival the New Music Quartet in following Beethoven's metronome markings), but nonetheless rhythmic and exciting. One of the best performances in the Philips cycle.

Both the Vegh and the Italian are generous but not compulsive about repeats. Phil ips' sound is rather similar to Telefunken's in the welcome prominence of the lower voices, and the Philips pressings too are superb.

H.G.

BIRTWISTLE: The Triumph of Time; Chronometer'. BBC Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Boulez, cond.; tape realization by Peter Zinovieffs. ARGO ZRG 790, $6.98

It's marvelous how a properly chosen visual image can color and direct one's reaction to a piece of music. One can't hear Hindemith's Concert of the Angels without seeing Mathis Granewald's celestial musicians flying about; similarly, Pieter Brueghel's engraving called The Triumph of Time, well reproduced on the sleeve for this record, dominates one's feelings about Harrison Birtwistle's magnificent score.

In his notes, Birtwistle says the musical ideas he employs here had already crystallized before he saw the picture, and he paraphrases Beethoven's "more an expression of feeling than tone painting." Nevertheless, he goes on to draw parallels be tween his work and Brueghel's, especially in their slow, inexorable march. That sounds romantic and obvious, more like Mahler than Birtwistle, but the music doesn't; it sounds like Birtwistle and him alone.

The engraving is a very complicated allegory. Time rides in a cart pulled by the horses of day and night. calmly devouring one of his own children and surrounded by every conceivable symbol of impermanence, destruction, decay. oblivion. Birtwistle speaks of his work as suggesting "the over-all image of the procession: a freeze frame; only a sample of an event already in motion; parts of the procession must al ready have gone by, others are surely to come; a procession made up of a (necessarily) linked chain of material objects that have no necessary connections with each other...."

The music grips one's attention from the first note and holds it through a symphonic fabric as bitterly magnificent and as devoid of sentimentality, good nature, or affirmative escape as Brueghel's colossal print. The performance by Pierre Boulez and the BBC Symphony is as fine as the score, with that perfect clarity, that sec quality that is so characteristic of Boulez.

Chronometer, on the other side, is a tape piece based or the sounds of all manner of clocks and clock-bells, some of them clearly identifiable in terms of their sources, some completely transformed.

The record reminds me a little of those percussion pieces put out in the early days of stereo to amaze us with the fidelity of the sound and with the fact that it could be made to come now from one speaker and now from the other. And several times during the course of Chronometer the sound seems to project itself free of the speakers and to exist in space before you. But this is no audio trickster's piece of jugglery. If The Triumph of Time sounds like Pieter Brueghel, Chronometer sounds like Hieronymus Bosch; those creaks and croaks and shrieks and gallopings could come only from the great Flemish artist's depiction of hell. A.F.

++++++++++++++++++++

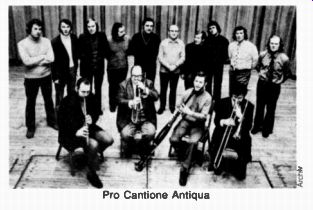

Pro Cantione Antigua

Bringing the Fifteenth Century to Life

by Susan T. Sommer

REVIEWING EARLY MUSIC can be a disheartening task; so often the repertoire or the performances are undistinguished. In Archiv's new collection of Dufay and Dun stable motets, we now have a recording that reveals the sheer musicality of these major works of the fifteenth century on their own terms. The combination of magnificent music and superb performance makes this one of the most beautiful records I have ever heard.

The iso-rhythmic motet is a triumph of musical organization, a structure of hierarchic rhythmic patterns reflecting an organic unity and proportion that, according to the medieval mind, mirrors the proportions governing the universe. It is easy to describe iso-rhythmic techniques in forbid ding intellectual language; intricate repetitive patterns lend themselves to intricate repetitive prose, too often irresistible to the theorist or the historian. It is more difficult to recall that these motets were written by musicians, and it takes a human performance to remind us of the humanity of their creators.

There are four iso-rhythmic motets on this disc: the splendidly elegant Supremum est mortalibus and the early Italianate Vasilissa ergo gaude by Guillaume Dufay, and Preco proheminencie and Veni Sancte Spiritus by his great English contemporary, John Dunstable. The uncompromising structure of the Dunstable works, which bring together pre-chosen melodic, rhythmic, and symbolic patterns in a dazzling set of combinations, makes them potentially even more forbidding than the Dufay mo tets. Interspersed among these monumental creations are five songlike motets--no less wonderful, but warmer and sweeter in their effect on the listener. One recalls the brilliant fan vaulting of a late Gothic cathedral, the glow of a Van Eyck altarpiece.

But cathedrals are there for the looking, at least for those who can afford the trip. Music, on the other hand, is dependent on the performance, and performance of early music has had to wait for a good deal of scholarly spadework and instrumental training before even the outlines of the artifacts began to appear. The past quarter century has seen an explosion of musicians who specialize in the pre-baroque styles. But technique, even virtuoso technique, is not enough to make a truly great musician. Great music speaks through the heart as well as the body, and it must be absorbed into the heart in congenial surroundings.

Even the greatest performers need to live with a piece or a style before they can share its life and communicate it to others. With this record, masterpieces of early music have finally been united with the technique to perform it and the understanding to bring it to life after centuries of oblivion.

What is it about Bruno Turner and the Pro Cantione Antique's performance that leads me to such unaccustomed rhapsody? Although the group is relatively new, I have not always enjoyed its recordings. Occasionally it is too austere in its sound and too unremitting in its tempos for my taste. In the Dufay and Dunstable motets, however, a small ensemble made up of the very best singers of this music makes a sound that is clear but never cold, beautifully molded to the subtle contours of the melodic curves yet bright and forthright when the music calls for precise definition. The instrumental support of the rebecs and winds, when it is used, underscores the lines without obscuring the essentially vocal nature of the music. The lyrical performances of Dufay's exquisite Flos florum and Alma redemp torts Mater by Paul Esswood and James Bowman respectively can only be matched for beauty of sound and subtlety of dynamics by the trio of lower voices, Ian Partridge, James Griffett, and David Thomas, in Dunstable's warm but spacious Salve Regina.

The isorhythmic structures are so delicately balanced that only when they move at the right speed in their own atmosphere can all the pieces fall into place. In this set, the tempos are ideal. Suddenly the ear can perceive the complex but logical and completely satisfying way in which separate and distinct melodic and rhythmic lines interrelate. It is a breathtaking experience.

Now it is all available for anyone with $8.00 on this fine Archly disc. The sound is of high quality throughout; texts and translations are provided, and the trilingual notes by Turner are interesting enough to inform and perhaps encourage listeners to learn more on their own.

DUFAY AND DUNSTAILE: Motets. Pro Cantione Antigua; Hamburg Wind Ensemble for Old Music, Bruno Turner, cond. [Andreas Holschneider and Gerd Ploebsch, prod.] ARCHIV 2533 291, $7.98.

DUFAY: Supremum est mortalibus, Flostlorum; Ave virgo quae de caelis; Vasiiissa ergo gaude, Alma redemptoris Mater. DUNSTAIILL Vern Sancte Spintus; Salve Regina; Beata Mater, Preco proherninencie.

++++++++++++++

Bosom: Quartet for Strings, No. 1, in A. Borodin Quartet. ODYSSEY/MELODIYA Y 33827, $3.98.

The work that the Russian music specialist M. D. Calvocoressi hailed as the earliest first-rate example of chamber music by a Russian composer was not the well-known Tchaikovsky First Quartet of 1871 or the Borodin Second (famous for its Notturno slow movement) of a decade later, but the now practically forgotten Borodin First of 1875-79. That quartet once enjoyed considerable esteem, and Borodin himself, only a month or two before his untimely death, relished the news that it had been success fully performed overseas, in Buffalo, New York. Yet when has it been played recently in this country? I wonder how many discophiles own one of the only two recordings I can trace, both by the Vienna Konzerthaus Quartet for Westminster: first a 1950 mono LP, then a 1983 stereo disc that apparently won scant attention although it didn't go out of print until 1971.

It's a joy to report that the present resuscitation of this unjustly neglected work, appropriately carried out by the Russian ensemble named after the composer, eloquently demonstrates not only Borodin's generally acknowledged inventive powers, but formal and contrapuntal skills extraordinary for an amateur and self taught musician, as the chemical engineer was presumed to be. And even if the work itself were less immediately delectable than it unmistakably proves to be, this disc still would be a "must" for the infectious enjoyment and (at times almost too much) enthusiasm with which it is played- a radiance fully captured in the glowingly warm Melodiya recording. Add Boris Schwarz's help fully informative jacket notes and a budget price to make up a true best buy! R.D.D.

BRAHMS: Violin and Viola Sonatas. Pinchas Zukerman, violin and viola; Daniel Barenboim, piano. [Gunther Breest, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 058, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Sonatas for Violin and Piano: No. 1, in G, Op. 78: No. 2. in A. Op 100; No. 3, in D minor. Op. 108; Scherzo in C minor, from FAE Sonata. Sonatas for Viola and Piano: No. 1, in F minor, Op. 120. No. 1; No. 2, in E hat, Op. 120, No. 2.

The Brahms violin sonatas have always been handsomely represented on records, with a discography that includes such memorable performances as those of Busch /Serkin (Nos. 1, 2), Szigeti/Horszowski (No. 2), Szigeti/Petri (No. 3), Kochanski/Rubinstein (No. 3), De Vito/Fischer (Nos. 1,3), and Goldberg/Balsam (Nos. 1-3). Even so, there is always room for a new edition as passionate and resplendently reproduced as the new Zukerman/Barenboim set, which is fully competitive with the best.

As might be expected. Zukerman and Barenboim treat the music in all-out emotional fashion. Their tempos are for the most part leisurely, with a good deal of expressive leeway. Zukerman's vibrato is lavish, but his sound is so potent and intense that one gladly accepts the excesses when they come. Barenboim plays with enormous sweep and energy; yet in the violin sonatas. at least, he never covers his partner. His is rugged. bass-oriented Brahms playing-heeding finer details, but mostly pursuing a grand line and quasi-orchestral contrasts and sonorities. He achieves considerable textural contrasts, even though his is not a particularly colorful style. Best of all, one senses an unfailing continuity and architecture despite the momentary indulgences. The sound, from New York's Manhattan Center, is rich and sonorous.

There was no logical reason for making this a three-record set, for the three violin sonatas and the early "FAE" Scherzo are accommodated neatly on the first four sides. I suspect that many will regret that the third disc, with the two viola sonatas, was included, for the performances are far less persuasive. The most serious problem is faulty balance, probably the result of several factors.

First, I would guess that Zukerman is less secure on the viola than on the violin, which he has been playing brilliantly most of his life. His viola playing here is not exceptional: The sound has nowhere near the soaring projection of his violin playing.

(The tone is rather scrappy and uneven. with an irregular vibrato and fractionally unreliable intonation.) Second, Zukerman ...

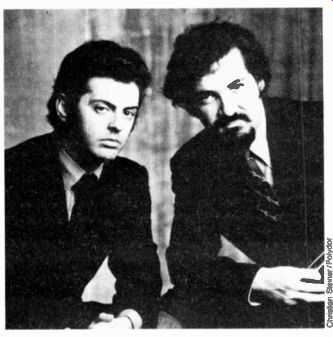

--------- Daniel Barenboim and Pinchas Zukerman- Passionate and resplendent

Brahms violin sonatas.

... puts himself at a further disadvantage by adhering to Brahms's own frequently gauche transcription from the clarinet-sonata originals, a case of absurdly misplaced purism. The composer doesn't seem to have fully comprehended the viola's possibilities as a solo instrument, and viola technique has improved immensely since his day: as a result. certain adjustments must be made for the music to sound properly. While Brahms's octave lowering occasionally pro vides a luscious sonority that the clarinet could not duplicate, much of the time the downward transposition makes no sense at all (except to accommodate less-skilled players), and in that register much of the passagework is simply covered by the piano. Twice in the first movement of the E flat Sonata Brahms begins a descending line in the viola's "comfortable" middle register and then, in mid-phrase, has to shift upward when he runs out of notes! Even granting that handicap. Zukerman's musical grasp of the viola sonatas seems far less imaginative than in the violin sonatas, and Barenboim too sounds far less at home.

The keyboard rendering alternates between excessive preciosity (the drooping tempos and languishing reverse accents in much of the E flat Sonata) and boorish inconsiderateness (the contrived rubato when the piano takes the main theme near the beginning of the first movement of the F minor Sonata). Unlike the violin sonatas, the viola sonatas have not been well treated on disc.

There are exceptions: The Primrose/Firkusny coupling (Seraphim 60011) has plenty of temperament and dash, not to mention the sheer beauty of Primrose's sound; Primrose also uses a judiciously edited version of the solo part (his own?) that keeps much of what is good in Brahms's arrangement but a It urds the viola greater brilliance when needed. For my taste, however, the slightly placid performances by Georg Schmid and Magda Rusy (MHS 691) come closest to conveying the true character of these elusive works, in particular the E flat Sonata. Although Schmid. like Zukerman, uses Brahms's text.

he gets better balance from his pianist and recording engineers. H.G.

Murree.: Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra-See Prokofiev: Cinderella.

CARTER: Double Concerto for Harpsichord and Piano with Two Chamber Orchestras*: Duo for Violin and Piano'. Paul Jacobs, harpsichord; Gilbert Kalish, piano; Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, Arthur Weisberg, cond. Paul Zukofsky, violin; Gilbert Kalish, piano. [Helmuth Kolbe and Joanna Nlickrenz, prod.] NONESUCH H 71314, $3.96.

The condition of dichotomy is fundamental in much of Elliott Carter's recent music, and the present coupling brings together two intriguingly different manifestations of the principle. In each case, the tonal contrast between two instruments is the germinal force of the piece. with all the musical dimensions aligned to dramatize that basic opposition of sonic character.

The Double Concerto (1961) surrounds each of the keyboard instruments-the harpsichord with its plucked strings, the piano with its struck strings--with a chamber ensemble that develops its material from the character of its respective solo instrument. Between the first rustlings of the metallic percussion and the final click of the claves, Carter creates a world of sound-or, rather, two worlds of sound that fade in and out, contrast, coalesce, collide, and finally disintegrate. There is wit here, and high drama in the slow movement, where, after accelerating and decelerating patterns have woven circles (literally, in space) around solemn sustained winds, the key boards compete in cadenzas, the piano out pacing the harpsichord and then, so to speak, outrunning itself in frantic accelerando, leaving a breathless silence to be timidly broached by silvery bell sounds.

There is virtuosity unbounded and color-not only for the soloists, but also for the four percussionists. With all its complexity, the Double Concerto is very much a gut experience: One feels the players strained to limits, and one feels the shape of the piece very directly-its tensions and climaxes, its growth, stasis, and collapse after the final tearing confrontation of the two groups with their irreconcilable musical habits.

This new recording-the third to date of the Double Concerto-is the best yet. From this statement should be inferred no slight on its predecessors, both of which represented "the state of the art" when they were made. There are valuable things to be heard in them, especially the crystalline brio of pianist Charles Rosen. But the piece has been played ever more frequently in recent years. and perhaps most frequently by the Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, yielding a tangibly more cohesive execution of many details. The openness and clarity of the recording helps, too.

The Duo for Violin and Piano is one of two chamber works that Carter completed in 1974. (A recording of the other, an ebullient brass quintet, should be along from Columbia soon.) Here the dichotomy of sonority is unadorned: The sustained tone of the bowed violin is set against the constantly decaying tone of the piano, without external mediation. Alongside the concerto, the colors are austere, and so is the argument. The piano begins with long notes, the violin with much activity, and the roles develop from there, alternating aggression and withdrawal. Again, the utmost in virtuosity is demanded, and the performance is pretty remarkable. I could wish for kinder sounds, and less rhythmic freedom, from Paul Zukofsky's violin; the close miking lends a raspy quality that is not, I think, part of the work's own character. Gilbert Kalish's playing is, quite simply, fabulous in its accuracy and directness.

Illuminating notes by the composer complete another of Nonesuch's admirable contributions to the recorded literature of American contemporary music.

Dasussr: Piano Works. Aldo Ciccolini, piano. SERAPHIM S 60253, $3.98.

Suite bergamasque; Pour le piano; Deux Arabesques; Reverie; Ballade; Dense.

Ciccolini rightly plays these works in a "romantic" rather than "impressionistic" style. He has plenty of color and nuanced delicacy but is not loath to accent boldly and take rhythmic license: His controlled yet swashbuckling treatment does wonders with the Preludes of Pour le piano and the Suite bergamosque. Ciccolini's ostinato playing is remarkable in the Menuet and Passepied of the Suite bergamasque. while sensuality and formal considerations are ideally blended in songfully meditative pieces like "Clair de lune" from the Suite and the Sarabande of Pour le piano, Reverie, and Ballade.

The rippling filigree of the two Arabesques doesn't preclude attention to larger basic structure-note how Ciccolini adroitly builds the chordal superstructure behind No. 2's scintillant figurations. The superbly vital, symphonic. and angular statement of the Danse reminds the listener of the rhythmic innovations that prompted the work's original title, Tarantelle sty rienne; the spirited little piece could scarcely sound more orchestral, even in Ravel's 1925 orchestration.

An irresistible bargain, with a distinct plus in the sharply etched yet impactively atmospheric reproduction.

H.G.

Dvorak: Slavonic Dances; Legends; et at For an essay review, see page 77.

FAURE: Barcarolles (13). Jean-Philippe Collard. piano CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CS 2078. $6.98.

Like so many musical terms, "barcarolle" can be applied to a broad variety of styles; about all that is expected is a mildly rocking 6/8 or 12/8 rhythmic flow. Faure's thirteen barcarolles, composed between 1883 and 1921. range in genre from the sicilienne (No. 4 in A flat. Op. 44) to the nocturne (No. 10 in A minor, Op. 104: No. 2 in G, Op. 41; and at least the openings of several others). For all that variety, the barcarolle remained especially suited to Faure's unparalleled gift for writing lovely keyboard figuration. The supple filigree continually weaving its way in short ripples back to the point of departure beautifully enhances the essential barcarolle lilt. In addition to the stylistic variety, Faure's harmonic language ranges from a Chopinesque fullness in the early barcarolles to an almost inscrutable vagueness in the later ones. In No. 7 in D mi nor. Op. 90. the occasional appearance of some rather Debussyesque chords leading to unexpectedly romantic resolutions creates some startlingly rich effects.

Unless you want the complete Faure piano music, in which case Evelyne Crochet's sets on Vox (SVBX 5423 and 5424) are recommended, Collard's recording of the barcarolles is a must. These are much warmer, more resonant performances than lean Do yen's on Musical Heritage (MHS 1772. September 1974), made so by Collard's fluid pedaling and his beautifully rounded tone definition. One or two pieces with minor flubs might have been redone, and the sound quality is not brilliant, but these are minimal drawbacks in an otherwise exceptional album. R.S.B.

Guam: Symphony No. 3, in B minor, Op. 42 (Ilya Murometz). Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra, Nathan Rakhlin, cond. Columbia /MELODIYA MG 33832, $7.98 (two discs, automatic sequence).

Comparison Ormandy /Philadelphia RCA LSC 3246 Whether one considers duplications the bane or the glory of today's enormous discography treasure house, it's not too often that we can profitably compare two versions of the same work that are both first rate in distinctively different, wholly com plementary ways. Back in June 1972 I wrote a rave review of the incandescent recorded performance by Ormandy of the apotheosis of symphonic romanticism, Gliere's Ilya Murometz Symphony. That achievement still sounds as thrilling as ever, but now whatever it may have lacked is supplied by the new Melodiya recording, and its every merit is paralleled by comparable (or even superior) yet markedly contrasting merits.

Most significantly, at least to purists, the new version is complete-the first such full score recording since the Scherchen/West minster mono set of 1953. It runs a bit over fifteen minutes longer than Ormandy's moderately cut, almost exactly hour-long reading (although Rakhlin's often slower, indeed often nobly deliberate tempos ac count for part of the longer duration), and it's almost twice as long as the cruelly abbreviated 1958 Stokowski/Capitol edition currently available in a Seraphim reissue.

Rakhlin--who hasn't been heard on records, as far as I know, for a good many years-proves that in the interim he has grown into a truly magisterial conductor able to provide a reading of impressive epic breadth, virile dramatic impact, and rhada manthine somber power. Where Ormandy is sensuously poetic and his Philadelphians tonally opulent, Rakhlin is spellbindingly bardic and his Moscow orchestra tonally darker and rougher but muscularly grip ping. The recording techniques, too, are no less polarized: RCA's glowing, lucid, softly focused; Melodiya's more sharply focused, more vividly realistic, and boldly "ringing." For many home listeners nowadays the musical adventures of the mythical bogatyr Ilya Murometz may seem too highly ro manticized as well as far too long even in Ormandy's trimmed-down version. But, al though they may fear that the still longer and far more grimly "Russian" Rakhlin version may be more than they can stand, they are sure to be jolted if not transfixed by its potent basilisk fascinations (or at the very least by programmatic evocations and sonic scene painting that put the best Hollywood film scores to shame). If for nothing else, this release is surely unique for the in credibly sustained intensity of many of its passages and for the almost imperceptible rises in its monumentally long crescendos.

At the reduced price of this two-disc set, there can be no complaint over the fact that the third side contains no more than the eight-minute Scherzo, especially since this enables the symphony's four movements to be distributed unbroken, one to a side.

R.D.D.

GOTTSCHALK: Piano Works, Album 2. Leonard Pennario, piano. [Patti Laursen, prod.] ANGEL S 36090, $6.98. Tape: 9* 4XS 36090, $7.98; e , 8XS 36090, $7.98.

Battle Cry of Freedom, 0. 62: Berceuse, 0. 27; Mazurk in F sharp minor, 0. 298; Grand Scherzo, 0. 114; Polka in B flat, 0. 273. Tournament Galop. 0. 264; Columbia, 0. 61; Marguerite, 0. 158; La Gallina, 0. 101; Ballade. 0. 271; 0. ma charmants. 6pargnez-moi. 0. 182; Suis-mois. 0. 253.

Unlike most sequels, this one (to Angel S 36077, March 1975) proffers just as brilliant playing and recording and even more imaginative and rewarding programming. At least four of the twelve selections here are, to the best of my knowledge, recorded firsts: the irresistibly toe-tickling, flashily virtuoso grande valse brillante, Marguerite, and three little pieces rediscovered only recently and published last year by the New York Public Library-the now sparkling, now nostalgically songful Mazurk, the amusingly insouciant if old-fashioned Polka, and the gentle, disarmingly simple Ballade.

But if the rest of the program is not brand-new, it is exceptionally well varied- from the jingoistic Battle Cry of Freedom through such catchy divertissements as La Gallina, Suis-moi, and the Tournament Galop to the truly charming O, ma charmante and the salonish Berceuse. And all is topped by two of the composer's master pieces: the truly grand Grand Scherzo and the fascinatingly jaunty Columbia rhap sody on Foster's "My Old Kentucky Home." As in his earlier program, Pennario plays with obvious relish and dazzling bravura- lacking only the more relaxed and lilting grace of the best Gottschalk performances by Eugene List, just as the glittering sonics lack only a warmer acoustical ambience.

R.D.D.

HANDEL: Organ Concertos (12). Herbert Tachezi, organ; Vienna Concentus Musicus, Nikolaus Hamoncourt, cond. TELEFUNKEN 38.35282, $20.84 (three discs, manual sequence)

HANDEL: Organ Concertos (16). E. Power Biggs, organ; London Philharmonic Orchestra, Adrian Boult, cond.

COLUMBIA D3M 33716, $13.98 (three discs) [from K2S 602, 1958, and M2S 604, 1959].

The Handel organ concertos, most of which were written for performance between acts of the composer's oratorios, are one of the high points of baroque chamber music.

They raise particularly difficult performance questions-and not only those of ornamentation, always a problem area in baroque music. Handel's notation here is especially sketchy: For example, not only are the cadenzas left to be improvised by the organist, but frequently, also, lengthy passages within the main body of the movements and even entire movements. In this and other regards, these two sets of recordings provide a fascinating, instructive comparison.

The Columbia release, a bargain reissue of the Biggs/Boult version originally issued in separate two-discs sets, takes an essentially "traditional" position. Although a baroque organ is used (one apparently often played by Handel himself), the orchestral instruments are modern. Ornamentation is kept to a minimum; the improvised sections, when included at all, tend to be short in length and tame in conception. Several of the movements to be entirely improvised are simply omitted, and in one of these, marked Adagio e Fuga (in Op. 7, No. 3), only the Adagio appears. Dynamics remain essentially constant for given musical segments, producing the well-known baroque "terraced" effect, and tempos are on the slow, safe side.

Herbert Tachezi and the Vienna Concentus Musicus present a very different picture of this music. A hallmark of the group is the use of authentic instruments, and this holds here both for the organ and the orchestral instruments. (Another difference is the use of harpsichord as a continuo instrument.) As a result, the ensemble balance is quite different: The organ is better able to hold its own in tutti passages, where it is completely inaudible in the Columbia version-indeed, I suspect it usually is not playing at all; and the woodwinds (mainly a pair of oboes, almost always playing in unison with the first and second violins) have a much more telling effect on the over-all sonority. But beyond such specific matters, the sound is in general much less homogeneous than is the case with modern instruments, not only when various instruments play simultaneously. but also within the playing of an instrument alone, where timbre varies considerably depending upon register, dynamic level, or both.

This last point is related to another important matter: Tachezi, Harnoncourt, and the Concentus Musicus do not accept the absence of dynamic detail in Handel's score as an indication that constant levels are to be maintained within each musical segment. Rather, they take this as an invitation to inject their own performing personalities into the score, an accepted practice in baroque times. This lends their playing a higher degree of variety, particularly evident in the use of dynamic swells over short groups of notes.

Perhaps the most noticeable difference, however, is the vastly more adventurous attitude toward ornamentation and elaboration. Handel's basic two-part organ writing is more consistently filled out with inner voices, and the ornamentation is both freer and more extensive. Moreover, repeated sections (always taken, another significant distinction) are normally treated as opportunities for variation and elaboration. The cadenzas, improvised sections, and improvised movements are longer and musically more developed. Finally, the whole approach to the baroque style is much more aggressive and sharply focused: Tempos are brisk, trills begin off the principal note (Biggs usually ignores this generally accepted baroque practice), and individual voices are differentiated in articulation.

In fairness it should be said that the Biggs /Boult set is certainly successful within the framework of its assumptions.

But after hearing the new recording it is impossible not to be struck by the relative lifelessness and, above all, the lack of surface color of the older one. This is not to say that the Harnoncourt version is entirely without problems. Details of articulation are often slavishly adhered to in the larger ensemble, so that frequent recurrences of material-as in the opening movement of Op. 4, No. 1- result in a certain stiffness. Also, tempos are occasionally so flexible that continuity is lost, as happens in the first movement of op. 7, No. 5, where the slower tempo of the sections for organ alone repeatedly interrupts the forward motion and produces a mannered effect.

Despite these minor reservations, the Telefunken set provides a wonderful ex ample of how fresh baroque music can sound when approached in a spirit of re creation. (It is ironic that the "old"--i.e., original-approach to this music seems to create a much livelier and more "up-to-date" quality.) The Columbia reissue is admittedly a bargain. And even with the crowding of four discs onto three, the sound re mains remarkably clean. (It should be noted that nothing from the original sets has been lost in the transfer. Repeats are frequently omitted and in one case-the second Menuet of Op. 7, No. 3-a complete movement is missing, but these were missing before.) One also gets four additional concertos (published without opus number and based largely on other music by the composer). But the over-all superiority of the newer set seems evident.

R.P.M.

HENZE: Kammermusikl-X11; In Memoriam: Die weisse Rose. Philip Langridge, tenor.; Timothy Walker, guitar : London Sinfonietta, Hans Werner Henze, cond. [Peter Wadland, prod.] L’OISEAU-LYRE DSLO 5, $6.98.

Hans Werner Henze used to be the contemporary composer best-or perhaps, with Benjamin Britten, equal best-represented on records; their works were recorded al most as fast as they were written. What Decca/London did for Britten, Deutsche Grammophon did for Henze. But now Deutsche Grammophon has struck the whole of its extensive Henze series from the British catalogue; in this country, only three of the DG records remain. The Decca/ London group has come to Henze's rescue, with this new Oiseau-Lyre release and, on its Headline label, Composes and the Sec ond Violin Concerto (to be reviewed next month). Kammermusik, as it seems to be called now, was originally entitled Kammermusik 1958, with the subtitle "uber die Hymne 'In lieblicher Moue' von Friedrich Holderlin." It belongs in time and in spirit with Henze's Kleist opera Der Prinz von Homburg (also composed in 1958), in which a romantic German prince is lost in classical dreams, amid a world of Prussian militarism. And it precedes the outpouring of love music in the early Sixties: Ariosi, Being Beauteous, the Cantata della Baba estrema. It is an other manifestation of that encounter that seems to be the inspiration of so much Ger man art from Goethe onward-between the German poet/painter/composer and Mediterranean antiquity. As Henze puts it: This time it is an encounter between Ger many and Greece in the vision of a poet whose mind is clouded with madness, who stammers in fragments with beautiful, apparently incoherent phrases. I can feel and understand this link to the ancient world. In our eyes, our landscapes alter and take on Hellenic features.

Holderlin's translations of Antigone and Oedipus Rex have been set by Carl Orff.

Britten has composed a Holderlin cycle.

Holderlin (1770-1843), like Goethe and Schiller, looked to ancient Greece as a Golden Age but mingled his dreams of an tiquity with an ardor for the restoration of that age. His writings, in the words of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, "are the production of a beautiful and sensitive mind"- but it was also a mind increasingly disturbed; from 1807 he was in an asylum.

What once seemed mad came in time to seem modern; Stefan George and Rilke are his disciples.

The beautiful text of In lieblicher Bldue is furnished with the record, and also-but not in parallel, not even on the same page- an English translation. Henze's Kammermusik-and this is nowhere made plain-is not simply a setting of it, but a series of twelve movements. Three movements are for the instrumental octet (clarinet, horn, bassoon, and string quintet), three are for tenor and guitar, three are for tenor and the instruments, and three are "tentos" for the guitar solo. (Is "tento" a form of the Spanish tiento, a kind of ricer car?)

These Three Tentos have been re corded separately by Julian Bream, on RCA LSC 2964. In the score, each is titled by a phrase from one of the songs.

So Kammermusik is at once a setting of and meditations and improvisations upon the Holderlin text. It was begun in Greece, composed to a commission from Hamburg Radio, first performed there and then soon afterward in England, where I heard it with its original soloists, Peter Pears and Julian Bream. Philip Langridge sings it very ably but without matching Pears's sensitivity to words, line, and tone; he is clear and steady, but there is not much sense of rapture.

Timothy Walker's playing of the guitar solos seems to me highly accomplished; I have not made a direct comparison with the Bream version. The London Sinfonietta instrumentalists are excellent-especially the clarinet of Antony Pay. The recording, in excellent balance, produces an effect of intimacy without cramping.

In 1963 Henze added an epilogue to the piece, for the octet-an Adagio to mark the sixtieth birthday of Josef Rufer. It includes a "semi-quotation" from Schoenberg's First Chamber Symphony. It is played here, and it is a beautiful piece of music.

In Memoriam: Die weisse Rose is a double fugue for seven winds and strings, written for the Congress of European Resistance Movements held in Bologna in 1965. "The White Rose" was an anti-Nazi student group that formed in Munich in 1942; its founders were executed a year later. The piece, a moving one, is mainly elegiac, with some dramatic incident. It is composed in the spirit of Bach's Musical Offering.

I have never been, or wanted to be, a per son who listens to and judges music "absolutely," uncolored by associations-in this case those brought to a hearing of Kammermusik by my own romantic feelings about Holderlin, Greece, and the German Greek encounter that has produced so much art I value. The allusive artists-Berlioz, Tippett, Henze, Crumb are examples who spring to mind-illumine, reinterpret, and enrich my imaginative world. Kammermusik can be analyzed and shown to be an excellent piece of construction. (So I discovered when working carefully through two movements to be sure of this; a study score is published by Schott /Belwin-Mills.) More simply, I would commend it as a romantic vision, "the production of a beautiful and sensitive mind." A.P.

MARTINU: Concertos for Violin and Orchestra, Nos. 1-2. Josef Suk, violin; Czech Phil harmonic Orchestra, Vaclav Neumann, cond. [Eduard Herzog, prod.]. SUPRAPHON 1 10 1535, $6.98.

The contrast between Bohuslav Martinfl's two violin concertos is all the more striking because both works immediately signal their composer. The First (1932-34) strikes out in directions that recall Albert Roussel, in the rather brittle vigor of the churning rhythmic language, and on occasion the Stravinsky violin concerto, in the some times acid leanness of the harmonic and instrumental textures and the manner in which thp violin soars above them. The Second (1943) moves into a universe of much deeper emotivity, opening with the broad, dark, and calmly tragic lyricism of the first movement; clearing the clouds in the subtly giocoso, highly syncopated second movement; and ultimately bursting, as so often happens in the composer's music, into a hazy Brahms-cum-Dvorak sunlight in which the brooding overtones announced in the first movement have almost vanished.

Both works have immense appeal. I have always found the Second Concerto (which I knew via an old Artia recording with Bruno Belcik, also conducted by Vaclav Neumann) one of Martinu's most moving corn- positions, in spite of some awkwardness caused, it seems to me, by indecision as to which emotional direction to pursue. But the earlier work comes as something of a revelation. In addition to the neoclassical spaciousness and energy, there is intriguing use of instrumental effect, particularly striking in the strings/woodwinds/violin interplay opening the charmingly ingenuous second movement.

Both concertos put the violinist through quite a workout, demanding almost non stop playing and frequent shifts from wide range, leaping passagework to bursts of broad, soaring lyricism. But Josef Suk ob viously has this music in his bones; even the occasionally harsh bowing adds a not un welcome coarseness here and there. Suk's is a highly Slavic style, with a rich vibrato and a soulful tendency to swell in the midst of the most meaningful notes of certain melodic passages, and there is no question that it perfectly suits the composer's aims.

Neumann keeps the orchestra under excellent control-no small feat, as Martina tends to treat the solo violin as almost its equal. With Supraphon's decent, if unexciting, recorded sound, this record should at tract listeners of all musical persuasions.

R.S.B.

MATHIAS: Dance Overture, Op. 16; Invocation and Dance, Op. 17; Ave Rex, Op. 45'; Concerto for Harp and Orchestra, Op. 50'. Osian Ellis, harp: Welsh National Opera Chorale: London Symphony Orchestra, David Atherton, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.] L'OisEAu-1203E SQL 346, $6.98.

This recording of four works by William Mathias introduces the young Welsh com poser to American audiences.

Three of the works are short and fill one side of the disc. The Dance Overture is one of those brilliant, happy, breezy, folk-tune type pieces that are an English specialty; Vaughan Williams used to run up three of them every morning before breakfast.

Mathias is no Vaughan Williams, but the composition is nevertheless a pleasing ex ample of its tradition. In the Invocation and Dance the style takes on a slow introduction and develops a big climax; this is actually a short, one-movement symphony that should do marvelously on the semi pop concert circuit. Ave Rex is a delightful cycle of five carols for chorus and orchestra. It is much more rugged and brilliant than such things usually are but has a superlatively lovely slow movement to balance its vigor.

A harp concerto by a Welsh composer and with a soloist named Osian ought to be the last word in bardic weep-strain, laugh strain, and glory-strain. But Mathias' work is rather poky and academic, except in its Adagio appassionato, wherein it at least hints at its potentialities. A.F.

MOZART: Piano Works. Claudio Arrau, piano. PHILIPS 6500 782, $7.98.

Fantasy in D minor. K. 397; Fantasy/Sonata in C minor, K. 475/457; Rondo in A minor, K. 511.

Arrau has of late played strangely little Mozart for a pianist who plays so much Beethoven. This disc includes just those selections one might have expected to appeal to so "serious" an artist, perpetually in search of musical profundities. All four works are in a minor key and are either strongly influenced by Bach (the prelude like introduction to the K. 397 Fantasy, the highly contrapuntal K. 457 Sonata) or permeated by a vein of somber emotionalism.

The C minor Fantasy, K. 475, gets a compelling statement. Arrau's tone-solid, velvety, varicolored-is monumentally impressive, and he uses it with excellent taste in a moderately paced interpretation full of clarity and acumen. The rhythm is notably well sprung, and the phrase scansions are unfailingly logical. The Alberti bass at the beginning moves ahead at just the right measured clip, neither too ruminative nor too pushed. One constantly feels the important distinction between downbeats and secondary accents, and the many little personal touches never disrupt the metric progress. A truly three-dimensional performance.

The ensuing C minor Sonata. K. 457, I find less satisfying. This logical, impersonal view of tragedy makes its greatest impact in a sort of non-interpretation that merely un folds the phrases and formal dimensions with patrician, compassionate impersonality. Arrau tries to humanize the music by reading between the lines, and I don't think the lines can take it. Too often the rhythm becomes overloaded by little caesuras and adjustments, and the powerful gravity of the music is thus compromised. To cite just one unsettling detail: Arrau executes the trills at the beginning of the first movement directly after the upward arpeggios, so that they begin, or appear to begin, a fraction too soon.

The D minor Fantasy. K. 397, begins with a lot of caressing rubato and an unusually big sonority. At one point in the final D major allegretto section, Arrau takes a long appoggiatura in the left hand that strikes me as a shade willful and studied. Otherwise this is a relatively uncontroversial reading-robust and full-throated. "Full throated" also describes Arrau's treatment of the highly vocal A minor Rondo, K. 511.

His tempo is rather broad, his handling of the arialike passagework always ready to yield to some inflection or expressive de vice. A near-Chopinesque account, almost the opposite of Schnabel's severe, but equally perceptive, performance (Seraphim 60115). Try to hear this record for yourself. The pianism is exceptional in its articulation and voicing, even with Arrau's liberal ped aling. The interpretations are distinguished too, though except in the K. 475 Fantasy they lack some of the symmetry and spontaneity I want in Mozart. The technical work is up to Philips' usual superlative standard.

H.G.

Ockghem: Maria Motets. Prague Madrigalists, Miroslav Venhoda, cond. TELEFUNKEN 6.41878, $6.98.

An admirable selection of beautiful motets by one of the master composers of the Re naissance. Texts celebrating the Virgin Mary inspired Ockeghem to some of his finest works, among them settings of the famous Marian antiphons, Salve Regina, Ave Maria, and Alma redemptoris Mater, and a most elegant motet, Gaude Maria.

The performances by the Prague Madrigalists, the well-known Czech vocal and instrumental ensemble conducted by Miroslav Venhoda, are both expressive and vital. Still, they are occasionally marred by intrusive doublings and other instrumental hokum. Attractive, but perhaps not for pur ists.

S.T.S.

PROKOFIEV: Cinderella, Op. 87 (excerpts from the ballet) Britten: Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, Op. 34. London Symphony Orchestra, Andrew Davis, cond. [Paul Myers, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33891, $6.98.

Comparison-Cinderelle (complete): Rozhdestyensky Moscow Radio Sym.

Mel. /Ang. SRB 4102

Comparison--Young Person's Guide: Britten/London Sym. Lon. CS 6671

This is the Columbia-label debut of the up and-coming young British conductor who won the musical directorship of the Toronto Symphony last fall. And, since I've heard him on records before only as a continuo player, it's my first chance to realize how impressive his credentials are as a potential super-virtuoso.

Barely into his thirties, Davis already commands remarkable self-assurance, a sure, taut grip on his players, and genuine powers of personality projection. Here he gives high-voltage performances of such...

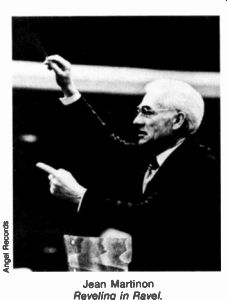

Jean Martinon--Reveling in

Ravel.

...disparate materials as thirteen of the fifty items in Prokofiev's Cinderella ballet and Britten's familiar orchestral Young Per son's Guide. (The Guide is done, as in the composer's 1964 London recording, without didactic narration. The latter was fine for the original sound-film presentation and in recorded versions for school or self-educational use but rapidly becomes superfluous in home listening.) Both performances are appropriately recorded with comparable forcefulness and vivid presence. But while this disc is likely to appreciate in value as a historical documentation of a world-famous conductor's early career achievements, I must qualify my commendation of it to aficionados of either Prokofiev or Britten in general or of these particular works. For Davis' (undoubtedly temporary) weakness is his present propensity for over-intensity, need less emphases, and even a suggestion of arrogance. As a consequence, his Cinderella excerpts lack the warmth and balletic grace of the 1967 Rozhdestvensky/Angel complete set (or of the 1962 Ansermet/Lon don disc of mostly the same selections), and his Young Person's Guide, electrifying as it is, lacks the more relaxed verve and humor with which the composer himself infuses this showpiece. Of course Davis' faults are characteristically those of an uncommonly gifted youngster, and he is still well worth hearing-and watching out for in the future.

R.D.D.

PUCCINI: Mass in A. William Johns, tenor; Philippe Huttenlocher, bass; Gulbenkian Foundation Chorus and Orchestra, Lisbon, Michel Corboz, cond. RCA RED SEAL FRL 1-5890, $6.98. Ouadriphonic: FAD 1-5890 (Ouadradisc), $7.98.

Puccini's Mass, a youthful work dating from 1880, remained unpublished-though not. as RCA's liner notes claim, unknown- until 1951. Father Dante del Fiorentino, who instigated the work's publication, called it Messa di Gloria, though its original title is simply Mass for Four Voices and Orchestra-the four voices being tenor, baritone, bass, and mixed chorus. There is no soprano solo.

In the twenty-five years that have followed the work's resuscitation, Puccini's Mass has hardly become a familiar repertory piece. The composer himself con signed it to oblivion and ransacked it for subsequent compositions: The opening of the Kyrie found its way into Edgar, and the charming, dancelike Agnus Dei became the madrigal sung at Manon Lescaut's Act II levee. Nevertheless, though it is unlikely that the Mass will ever make a wide appeal to concertgoers, one can only welcome a new recording of this unpretentious piece and say that, quite apart from its interest to Puccinians, it is at the very least easy to listen to. Hardly any of this music bespeaks religious conviction, but a great deal of it reveals the musical fluency-if not yet the quality, the sheer vigor, the sweep-that marks Puccini's mature operas.

Michel Corboz' performance, a little slack and easygoing, is disarmingly affectionate. Chorus, orchestra, and soloists are capable, I assume that Philippe Htitten-!ocher, listed as a bass, takes on both the bass and baritone assignments. The Erato recording is resonant. No text is supplied, and no notes on the performers. D.S.H.

RAVEL: Orchestral Works, Albums 1-2. Orchestre de Paris, Jean Martinon. cond [Rene Challan, prod [ ANGEL S 37147 and S 37148, $6.98 each SO-encoded disc.

Album 1: Bolero, Rapsodie espagnole; La Valse; She herazade Ouyerture de Merle. Album 2: Daphnis at Chloe (complete ballet; with Paris Opera Chorus).

The most novel item in the initial installments of Jean Martinon's new Ravel series is the previously unrecorded Sheherazade Overture, composed in 1898 for an opera Ravel never wrote. As it turns out, the over ture, though not without a certain Orient flavored charm, has more fluff than sub stance. Its excessive motivic repetitions and whole-tonisms give the impression of Debussy viewed through Dukas-colored binoculars. Furthermore, although the performances of the short works on Album 1 are fully competent, especially in the multi hued Bolero. I had the feeling that conductor and orchestra were not always in perfect sync.

But the Daphnis et Chloe! Of all the recordings of the complete ballet made so far, this is certainly the most satisfactory over-all. Martinon shows exceptional sensitivity in delineating the horizontal progression of the work's many episodes, al most sneaking up on its frequent shifts in direction before the listener is aware of them, so that the sense of balletic, as well as musical, flow develops in amazingly subtle waves. In addition, within the vertical structures he creates more depth of instru mental color than any other conductor, including the vertically oriented Pierre Boulez (Columbia M 33523, December 1975). Martinon obviously revels in Ravel's breathtaking tonal spectrum, which leads him to open the ballet in a manner some may find excessive. Yet never before have I heard the glorious instrumental expanse leading the spectator into Daphnis shaped with such richness. And throughout, the multiplicity of orchestral nuance enhances all of the ballet's other elements--in particular the harmonies, which take on an un canny fullness. The whole rendition lacks only a more energetic "Bacchanale" and a less sour flute solo toward the end of the "Pantomime" to make it definitive.

The recorded sound has a certain mellowness that characterizes a number of quadriphonic recordings I have heard in stereo. But there is no lack of brilliance and depth here, and, if Angel's sound does not match Columbia's in the hair-raising up front sonics given Boulez, it does seem perfectly molded around Martinon's conception of the work. And I must say that the mellowness of sound has a particularly good effect on the brass, which Martinon rounds out with special care throughout both of these records. Unfortunately the surfaces of my copies were less than great, and the Daphnis was also pressed badly off-center. R.S.B.

SCHOENBERG: Das Buch der hangenden Garten; Brettl-Lieder; Early Songs. For an essay review, see page 73.

SCUBERT: Sonata for Piano, in B flat, D. 960. Gabriel Chodos, piano. [Giveon Corn field, prod.] ORION ORS 75179 $6.98.

Chodos' interpretation of the Schubert B flat Sonata, one of the high points of the classical repertory, is planned along heroic lines, with elaborately pointed detail, grandiose tempos, and yet a pervasive directness and simplicity that I find quite touching.

Chodos repeats the first-movement exposition, and I approve wholeheartedly; the dramatic first ending, as I have previously noted, transforms a dreamy nocturne into a commanding edifice. The second-movement tempo rightly heeds the qualifying "sostenuto" more than the basic "andante"; the requisite flow is always present, but the music takes on a meditative seriousness that carries the listener hypnotically through all the magnificent changes of tonality. The scherzo, like Schnabel's, is moderately paced, yet delicacy is never seriously slighted in this precise, rhythmically reliable reading. The finale, while not overly fast, always moves with impetus.

Chodos' account of the sonata ranks with Curzon's (London CS 6801) and Michele Boegner's (MHS 1042) as the finest currently available. The piano sound could do with more richness and space around it, and my pressing was noisy. H.G.

SCHUBERT: Songs. Elly Ameling, soprano; Dalton Baldwin, piano. PHILIPS 6500 704, $7.98.

rn Abendrot; Die Sterne: Hecht und Trriume; Dec liebl lche Stern; Rosamunde: Romance; Dec Einsame; Schlummer lied; An Sylvia; Des Madchen; Minnelied; Die Liebe hat gelogen; Du liebst mich nicht; An die Laute: Dec Blumen brief; Die Manner sind nuichant Seligkelt.

This is another excellent recital from what must surely be the finest Lieder partnership today. "An die Laute," with its perfect ac cord between rippling accompaniment and lighthearted vocal line, is a good example of the rapport between Elly Ameling and Dalton Baldwin-and also of the extraordinary quality each artist achieves: the pianist with his subtlety of rhythm and certainty of touch, the soprano with her delicacy of manner and purity of style.

There is not a song here that they fail to bring to life. For example, "Der Einsame," that marvelously affectionate portrait of self-satisfaction, is as vivid as any version I know. By the time we get back to the cricket in the final stanza we have experienced an entire life-style. And, as always, Ameling never sacrifices the music for dramatic effect. The small but telling emphasis she gives to "bang" (anxious) in the first stanza of "Der liebliche Stern" is enough to mark her as an uncommon artist.

It ought to be mentioned that in the first part of Side 1, Ameling's voice does not sound as tonally pure as it usually does.

Whatever the reason, a couple of songs that call for sustained tone, like "Im Abendrot" and "Nacht und Treiume," are marked by a tone that is both cloudy and flickering. By the middle of the side all is well, and there after there is no impediment to one's pleas ure. The last song of all, "Seligkeit," is, in fact, as perfect a Lieder performance as I know.

The recording is a little close. There are texts (not always in agreement with what Ameling sings) and translations (some literal, some for singing). D.S.H.

SCHUBERT: Songs. For an essay review, see page 73

SMETANA: The Bartered Bride (in German). Mane Esmera, aa Ludmila Hata Hans Wenzei Teresa Stratas (s)

Janet Perry (s)

Margarethe Bence (s)

Gudrun Wevezzow (ms)

Rene Kollo (t)

Heinz Zednik (1)

Kruschina Kezal Spnnger Micha Muff Jorn W. Ohlsng (b)

Walter Berry (b)

Karl Donch (b)

Alexander Malta (bs)

Theodor Nicola! (bs)

Bavarian Radio Chorus and Orchestra, Jaroslav Krombholc, cond. [Hans Richard Stracke, Oscar Waldeck, and Theodor Holzinger, prod.] EURODISC 89 036 XGR, $23.94 (three SQ-encoded discs, manual sequence; distributed by German News Co., 218 E. 86th St., New York, N.Y. 10028).

Comparison: Lorengar. Wunderhch, Kempe EMI 1C 153 28922/3 Anyone interested in acquiring an authen tic Bartered Bride will have to search in specialty shops for one of the Supraphon versions that at various times have circulated in this country-either the 1960 Chala bala set or, better yet, the 1954 Vogel. The present recording is, of course, inauthentic.

Though the difference between Prodana Nevesta and Die verkaufte Braut is large4 a matter of vocal coloration and rhythmic stress, there is no doubt in my mind that the original Czech imparts a greater vigor and liveliness to Smetana than can ever be achieved in translation. Nevertheless, even [...] the opera Berry, who, intelligent artist though is, sounds out of his element in these rustic ca perings, for which he seems to lack the necessary common touch. The remainder of Krombholc's cast, however, is good. especiaily the Wenzel of Heinz Zednik. Orchestra and chorus are first-rate.

Heard stereophonically, the quadriphonic recording is extremely rich, though the highs sound constricted and the vocalists are too near the microphone. (Perhaps the latter has to do with the fadt. that, though made in a regular recording studio, the performance actually constitutes the aural portion of a Munich television production.) An eight-page booklet with photo graphs of the production and notes on the artists (in German only) is included, but no text. The German text used here is a new translation by Kurt Honolka; though it pre serves some of the familiar phrasing of Max Kaleck's old version, it is otherwise more up to date in diction and should have been printed in the booklet. D.S.H.

SMETANA: The Bartered Bride: orchestral excerpts. For a review, see page 77.

STRAUSS, R.: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30. Norman Carol, violin; Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, cond. [Jay David Saks, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-1220, $6.98. Tape: VI ARK 1-1220, $7.95; CI.] ARS 1-1220, $7.95. Quadriphonic: ARD 1-1220 (Quadradisc), $7.98; ART 1-1220 (0-8 cartridge), $7.95.

Comparisons: Ormandy/Philadelphia Col. MS 6547 Haitink Concertgebouw Phil. 6500 624.

No historically minded discophile is likely to find any recording that surpasses this one in documenting the changes in audio technology that have taken place since 1984, when Ormandy and the Philadelphians first recorded Zarathustra for Columbia. The earlier version was hailed as something of a sonic landmark in its own day (and indeed it still sounds mightily impressive), but the new one is-even in stereo only-a super-spectacular of the mid-Seventies.

If that's what you want in a Zarathustra, fine. If, however, you're more interested in the musical performance than its recording, you'll find no comparable interpretative growth in Ormandy's present reading: It's just as episodic, even more mannered (the violin-solo passages are much more saccharine), and generally more overtly sensationalized than before.

I find no real challenge here to such orthodox, portentously dramatic readings as the recent one by Susskind for Turnabout (QTV-S 34584), much less the transcendentally poetic one by Haitink for Philips, which for me continues to reign supreme.

Technically, the latter masterpiece also is far closer to what a fine orchestra actually sounds like in a fine hall, but I must concede that that is scarcely as hair-raisingly thrilling as some of the out-of-this-world sonics of this new RCA disc.

R.D.D.

STRAVINSKY: Concerto for Piano and Winds*: Ebony Concerto': Symphonies of Wind Instruments; Octet. Theo Bruins, piano"; George Pieterson, clarinet'; Nether lands Wind Ensemble, Edo de Waart, cond.

PHILIPS 6500 841, $7.98.

STRAVINSKY: Octet; Pastorale; Ragtime; Septet; Concertino. Boston Symphony Chamber Players. [Thomas Mowrey, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 551, $7.98.

Comparison: Stravinsky Col. M 30579, MS 7054 Here are two substantial helpings of Stravinsky, primarily from the middle period, including several works not currently available save in the composer's own versions.

First, let me offer almost unreserved praise for the Netherlands Wind Ensemble disc; in intonation, unanimity, balance, and dynamic precision, it pretty consistently surpasses earlier recordings. Chord successions are clearly and logically voiced, textural overlaps and augmentations are seamlessly achieved, and the phrasing never fails of sensitivity and (where appo site) wit. I like the way Theo Bruins's piano chordings match the weight of the wind sonorities, the feathery staccatos that George Pieterson achieves in the Ebony Concerto's last movement, the impulse and verve of all the playing, and the clean, natural recorded sound. I'll still hang on to the Stravinsky versions-they have a certain angular elegance, even at their most un kempt-but this Philips disc now takes pride of place for these four works.

The Boston disc doesn't reach quite the same exalted level but should prove useful nevertheless, for it supplements some of Stravinsky's least satisfactory recordings.

Notably among those is the Pastorale, in which the Columbia disc offers a limp oboist and a flat violinist. The Columbia Septet, which banishes the important piano part to the rank of distant accompaniment, is also of limited value, and here we have no trouble discerning the work of Gilbert Kalish (who seems to be on just about every record I review these days-a happy circumstance!). Ragtime may have more swagger at the composer's hands, but the new one is certainly neater. Honors are more even in the other two pieces, but this is certainly a record for Stravinskians to consider seriously.

D.H.

STRAVINSKY: Sonata for Piano, in F sharp minor. Tchaikovsky: Sonata for Piano, No. 3, in G, Op. 37. Paul Crossley, piano. PHILIPS 6500 884. $7.98.

The late Igor Stravinsky believed his early (1903-4) piano sonata to have been lost, but the manuscript was in fact preserved in the Leningrad State Public Library and (along with a 1902 Scherzo for piano) has recently been edited by Eric Walter White and published by Faber Music. Now the earliest Stravinsky work on records (it predates the Symphony in E flat), it is something less than a pre-figuration of future genius.

Like the symphony, and in some ways like the Tchaikovsky sonata with which Paul Crossley has ingeniously chosen to couple it, the Stravinsky sonata proceeds with a rather balletic squareness of phrasing, relying on repetitions and sequences to fill out its leisurely approximation of classical procedures. Neither of these sonatas is closely or concisely argued in the Beethovenian sense, or pregnantly, allusively discursive in the manner of the German Roman tics, although Stravinsky surely aims higher in terms of emotional weight, and none of his movements is as insubstantial as Tchaikovsky's fluffy Scherzo. Less than a decade from here to The Rite of Spring - that's a long way, and this record will let you measure the distance aurally.

Crossley strikes me as an admirable ad vocate, a clean and straightforward player who doesn't force the music beyond its expressive capabilities. I suspect that the showier bits of the Tchaikovsky could be still more effectively flaunted (perhaps Richter does that, on a Monitor record that I wasn't able to lay hands on in time), but that is no great matter. Philips' sound is gorgeously natural, and the surfaces are impeccable. D.H.

VivaLot Juditha triumphans

Vagaus Judaha Holofernes Abra Ozias Elly Ameling (s)

Birgit Finnila (ms)

Julia Haman (ms)

Ingeborg Springer (ms)

AnneIles Burmeister (ms)

Jeffrey Tate, harpsichord; Berlin Radio Soloists' Ensemble; Berlin Chamber Orchestra, Vittorio Negri, cond. PHILIPS 6747 173, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Vivaldi, his name a household word today, was a discovery of the twentieth century; we might even say that real appreciation of that eighteenth-century composer is no more than a generation old. At the opening of our century, writers on music began to wonder who this fellow was whose concertos Bach found good enough to transcribe for his own purposes. In 1903, when the German musicologist Arnold Schering published his important history of the instrumental concerto, the musical world suddenly became aware of the existence of a major composer hitherto unrecognized; then in 1948 Marc Pincherle's fine study and thematic index of Vivaldi's concertos made it clear that here was a key figure of baroque music.

Yet our picture is still incomplete, be cause with the exception of Corelli, who never wrote vocal music, most major com posers of the Italian high baroque made their reputation with operas and church music, and all we know of Vivaldi are comparatively few of his hundreds of concertos and the Gloria. Vivaldi research is still groping, made inordinately difficult by his more than usual baroque self-borrowings, lack of information about his activities be fore 1705, and the absence of reliable dating of his works. Surely "Op. 1," appearing when he was twenty-seven, could not have been the first work of this incredibly productive composer. The real unknown, how ever, is the operista, Vivaldi the dramatic composer. We must always remember the great influence opera exerted, from Monteverdi to Wagner, on all branches and genres of music, and Vivaldi was indeed a prolific composer of operas and concerted sacred music; one theater in Venice alone produced eighteen of his operas.

This was an age in which opera, oratorio, and cantata formed one large family of dramatic music. Even Carissimi, who com posed oratorios but no opera, is a pure musico-dramatist, and the Italian oratorio, in which the role of the chorus is minimal, can hardly be distinguished from opera. This recording of one of Vivaldi's two Latin ora torios is therefore most welcome as a representative specimen of a totally unfamiliar portion of his oeuvre. Since performance and recording are both excellent, and the conductor is also a musicologist who hews closely to the original manuscript from which the recording was made, we get a good and authentic glimpse of Vivaldi the dramatist.

While Bach had to struggle at the Thom asschule with a largely inadequate musical establishment, Vivaldi, at the Pieta, the great orphanage-conservatory in Venice where he was resident music master for decades (though there were some interruptions), had at his disposal superbly trained instrumentalists and singers. Re liable contemporary observers repeatedly stated that the orphaned-girls' orchestra was superior even to the famous Paris op era orchestra. So Vivaldi could experiment to his heart's content with a veritable laboratory. The consumption of music at the Pieta was enormous, and most of it was furnished by the resident maestro.

As we listen to Juditha triumphans, com posed in 1716, we soon realize that Vivaldi's style is a union of the two genres that were the epoch-making contribution of Italy to musical history: opera and the concerto.

Opera furnished new means of expression to instrumental music, while the concerto endowed opera with orchestral organization, also creating such subspecies as the aria concerto, i.e. arias with an obbligato solo instrument. A glance at Bach's arias in his cantatas and Passions will immediately confirm this. Recent research discloses that it was not only Vivaldi's exciting new genre, the concerto, that fascinated the German cantor, but his vocal music too; even the B minor Mass shows this influence.

Vivaldi was called the "Red Priest," but he was a redhead in more than one sense.

His impetuosity (which at times led him to sloppiness and mere sequencing) is vividly present in this oratorio, and without its ad verse features. The first aria in moderate tempo is No. 15: then we continue with unabated sprightliness, the violins dancing around the voices at top speed, until No. 27, and the next restrained piece is No. 46; but there is not one real adagio or largo in the entire work.

Vivaldi's coloristic imagination, unprecedented for his time, is present every where. In the rousing opening and final scenes, the trumpets and drums create a festive and triumphant clangor; in No. 15 a viola d'amore solo with the accompaniment of low strings conjures up most unusual sounds; other solo-with-strings combinations-clarinet, trumpet, oboe with organ, etc.-are equally original and surprising. One aria is accompanied by four large lutes and harpsichord, still another has a mandolino concertato with pizzicato strings-the variety is endless and the fine extended ritornels offer ever new so norities.

The arias are of the da capo variety. The writing is idiomatically vocal, though very demanding, as there are many extremely virtuosic coloratura passages-some of Vivaldi's girls must have been young Tetrazzinis. We have here a large work filled with prevailingly captivating music, but there are some features that considerably diminish our enjoyment of this splendor of color, good tunes, and rich imagination.