reviewed by: ROYAL S. BROWN ABRAM CHIPMAN R. D. DARRELL PETER G. DAVIS SHIRLEY FLEMING ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE HARRIS GOLDSMITH DAVID HAMILTON DALE S. HARRIS PHILIP HART PAUL HENRY LANG ROBERT LONG IRVING LOWENS ROBERT C. MARSH ROBERT P. MORGAN JEREMY NOBLE CONRAD L. OSBORNE ANDREW PORTER H. C. ROBBINS LANDON HAROLD A. RODGERS PATRICK J. SMITH SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

BACH: Canons on the First Eight Bass Notes of the "Goldberg" Aria. For a review, see page 84.

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1, in C minor, Op. 68. Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel, cond. [Michael Woolcock, prod.] LONDON CS 7007, $6.98. Tape: CA CS5 7007, $7.95.

After the broad introduction, Maazel begins the exposition of the First Symphony at a lusty speed, but within a couple of measures the pace slackens abruptly. Then, most curiously, when he observes the rarely taken repeat the exposition begins again without the initial brisk tempo. It goes that way throughout. A Luftpause here, a sudden emergence of some textural strand there, but no balancing of such de tails at analogous structural points. The reading turns into a series of random happenings, with orchestral playing to match.

For aficionados of the first-movement repeat, the excellent Kertesz/Vienna version (CS 6836) can be safely recommended. Levine's Chicago recording (RCA ARL 1-1326) is an object lesson in coherent virtuosity, American-style, and in urgent freshness of conception. For those who prefer Old World dignity, Haitink and the Concertgebouw (Philips 6500 519) speak a traditional tongue. If you want irresistible impulse, the recently issued Furtwangler/Berlin (DG 2530 744) indulges same with a sense of purpose and meaning. A.G.

--

Explanation of symbols

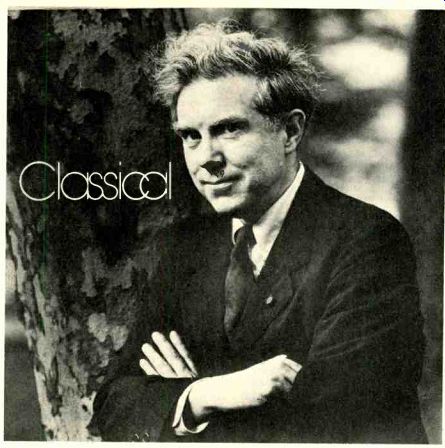

Classical:

B. Budget

H. Historical

R. Reissue

Recorded tape:

Open Reel

8-Track Cartridge

Cassette

--------

CARTER: Brass Quintet: Eight Pieces for Four Timpani: A Fantasy Elliott Carter-infinitely flexible mode of musical discourse About Purcell's Fantasia upon One Note. American Brass Quintet, Morris Lang, timpani'. [Thomas Frost, prod.] ODYSSEY Y 34137, $3.98.

As each new work takes shape, it becomes increasingly clear that the mode of musical discourse developed by Elliott Carter over the past three decades is infinitely flexible, capable of encompassing ever fresh expressive ends. Within this mode of discourse (a term I prefer to "musical language," which implies things-pitches, say, or harmonies, or specific gestures-rather than the relationships in which Carter's music deals most fundamentally), the composer can conjure up scenarios to suit any purpose and, more specifically, any instrumental combination. As if to demonstrate that flexibility, Carter has, since the big, turbulent Concerto for Orchestra (1969), produced several works for small combinations, each completely distinctive in its unfolding: the Third String Quartet (Co lumbia M 32738); the Brass Quintet here re corded for the first time; the Duo for Violin and Piano (Nonesuch H 71314); and the still-unrecorded song cycle with instruments, A Mirror on Which to Dwell, to poems by Elizabeth Bishop, his first vocal work in many years. (By the time these words appear in print, a new orchestral work will have been introduced-and re corded-by Boulez and the New York Phil harmonic.) In the Brass Quintet, the metaphors of conversation-discussion, argument, and so on-that some of us have applied to the string quartets still retain some applicability, but there are special twists to the work's progress. Among the five individuals, one (the horn) is "more individual" than the others-at times downright obstreperous. During the earlier course of the piece, the instruments take turns teaming up in contrasting duos and trios that alternate and overlap with sections in which each concentrates on his particular vocabulary of materials. Eventually the horn asserts himself strongly, in a cadenza to which the others respond with fierce and startling octaves. A second kind of climax is then reached by all five together (that is, "separately together," in the usual Carter sense), after which they fall back on the slow music that, since the beginning, has been heard frequently in the background.

This time the sustained notes form rich harmonies rising to an eloquent climax. This communal effort dissolves, but after recalling earlier arguments the characters in this drama do agree to settle on crescendo trills for an ending.

The writing throughout makes fantastic demands, both on the players' command of their instruments and on their rhythmic fluency. Brasses are by nature exuberant, and there is boisterous music-but also other kinds: Imagine trumpets slithering their way through the characteristic Carter scorrevole passagework that we know from the string quartets or the keyboard music.

At another extreme, the warmth of the slow movement recalls the solemn chorales that lie at the heart of the Double Concerto.

The Carter Brass Quintet is a challenge ambitious ensembles will find hard to resist, especially as set forth in this fine recording by the American Brass Quintet, who commissioned the piece. Its performance is simply amazing: In terms of ensemble, fluency, rhythmic and dynamic control, and tonal blend, it will be very hard to equal. As a token of gratitude, the quintet received from Carter a Christmas present, in the form of a splendid setting of Purcell's famous five-part Fantasia on One Note, which concludes the present disc.

Between the two brass pieces are sandwiched Carter's Eight Pieces for Timpani. a percussion parallel to the Eight Etudes for Wind Quartet. Six of these were written in 1949 and revised in 1966, at which time the other two (for pedal timpani) were added to make the present set. They can be a brave show in concert, where the player is visible (and these days most percussionists have cultivated a degree of visible showman ship)-although Carter asks in the score that not more than four be played at one time. I think this is worth keeping in mind when listening to the record; although the pieces are quite different, the medium is a limited one, and these are not "percussion spectaculars." Rather, except for the two 1966 pieces, which concentrate on glissando rolls and resonances, they are studies in rhythmical and metrical transformations-the kind of thing that lies at the base of the First String Quartet, finished in 1951.

Against the intentionally restricted back ground of kettledrum sound, one can concentrate on the shifting accents, groupings, and tempos; these are good "listening exercises" to prepare for the major Carter works--e.g., keeping track of how the two march tempos in the last piece are related, or how the gigue in the seventh piece turns into a waltz.

I have heard performances of the timpani pieces with more shape and dramatic flair than this one-though perhaps that impression was due in part to the visual aspect mentioned above. Like the rest of the disc, it is quite well recorded. The composer's liner notes are apposite and instructive. D.H.

GEMINIANI: Sonatas for Cello and Continuo (6), Op. 5. Anthony Pleeth, cello; Christopher Hogwood, harpsichord; Richard Webb, continuo cello. [Peter Wadland and Raymond Ware, prod.] L’OisEAU-LYRE DSLO 513, $7.98.

While Francesco ("The Furious") Geminiani (1687-1762) has been best represented on records by his concertos grossos, he was most important historically as a Corellian pupil violinist whom Handel was proud to accompany and as author of an influential treatise on the art of violin playing. But he also contributed a notable early work to the repertory of the cello, which had just begun to emerge as a solo instrument around, the beginning of the eighteenth century.

The present set of sonatas, published in London in 1747, has been occasionally rep resented on discs before now but usually only by a single example played on a modern instrument with piano accompaniment.

The L’Oiseau-Lyre release is triply significant for providing all six sonatas (in A, D minor, C, B flat, F, and A minor); for its realization of the continuo part by a harpsichord and second cello; and for the use of all period or replica period instruments, including even the cello bows. Better still, the young Pleeth's performances are authoritatively straightforward, he is deftly if less boldly accompanied, and the close, vividly sonorous recording is powerfully realistic.

Add a four-page trilingual notes--booklet that includes a facsimile of the original edition's title page, and we obviously have an invaluable discographic document.

But after having given it due honor, it must be added that the music itself, for all its harmonic and technical innovations, is not particularly interesting melodically or rhythmically. And the initially arresting, robustly gutty sonorities eventually tend at least for non-specialists-to become wearisome.

-R.D.D.

HANDEL: Double Concertos. No 1 in B flat; No. 3, in F. Overtures: Agrippina; Arianna. Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner, cond. [Christopher Bishop, prod.] ANGEL S 37176, $7.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

The Marriner all-Handel discography for Argo and Angel is becoming impressive quantitatively (three sets and five singles in the current Schwann-1 catalog), but it is even more impressive qualitatively. Marriner and his Academy players have the rare knack of generally coming at least close to satisfying musicologists in their insatiable search for stylistic historical authenticity while at the same time infecting non-specialist listeners with their own relish for the music itself.

The present program is no exception. And while the very early Agrippina Overture has been recorded before (notably by Richter for DG), as have these two of the three concerti a due cori (usually as fillers for Royal Fireworks Music releases), I've never heard any of them played with more piquancy and gusto or recorded with more vivid presence (in stereo-only as well as in quadriphonic playback). That's true, too, of the program's novelty, the first recorded version of the grandly expansive and excitingly driving overture to the 1734 opera Arianna in Creta. For everyone who shares my conviction that Handel's music at its best is incomparably satisfying and invigorating. this disc is not to be missed!

R.D.D.

-------------------

Critics Choice

The best classical records reviewed in recent months:

BACH: Cantatas Nos. 92. 126. Richter. ARCHIV 2533 312, Apr.

BACH: Flute Works. Robison, Cooper. VANGUARD VSD 71215/6 (2), March.

BARTOK: Bluebeard's Castle. Troyanos, Nimsgern, Boulez. COLUMBIA M 34217, Feb.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 6. Ferencsik. HUNGAROTON SLPX 11790, March.

BRAHMS: Violin Sonatas. Grumiaux, Sebok. PHILIPS 9500 108, 161 (2), Apr.

CHOPIN: Polonaises Pollini. DG 2530 659, Apr.

COUPERIN: Concerts royaux. Holliger et al. ARCHIV 2712 003 (4), Apr.

CRUMB: Makrokosmos II. R. Miller. ODYSSEY Y 34135, Apr.

Dvorak: Symphony No. 7. Davis. PHILIPS 9500 132, Apr.

GOTTSCHALK: Piano Works. List, Lewis, Werner. VANGUARD VSD 71218, March.

Listz: Concerto No. 1 et al. Gutierrez, Previn. ANGEL S 37177. Kiss, Ferencsik. HUNGAROTON 5LPX 11792 Berman, Giffin'. DG 2530 770. Feb.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 3. Home, Levine. RCA RED SEAL ARL 2-1757 (2), March.

MEYERBEER: Le Prophete. Scotto, Home, McCracken, Lewis. COLUMBIA M4 34340 (4), March

NIELSEN: Orchestral Works. Blomstedt. SERAPHIM SIC 6097, 6098 (6), Feb.

PAGANINI: Caprices (24). Rabin. SERAPHIM S'B 6096 (2), Apr.

ROSSINI: Elisabetta. Caballe, Carreras, Masini. PHILIPS 6703 067 (3), Feb.

SAINT-SAENS: Violin Concerto No. 3. VIEUX TEMPS: Violin Concerto No. 5. Chung. Foster. LONDON CS 6992, Apr.

SCHOENBERG: Variations, Op. 31 (with Eiger). Solti. LONDON CS 6984. Chamber Symphonies. Inbal. PHILIPS 6500 923. Apr.

SHOSTAKOVICH: Quartets Nos. 8, 15. Fitzwilliam Qt. L’OisEAu-LYRE DSLO 11. Cello Concerto No 2 Rostropovich, Ozawa. DG 2530 653. Feb.

STRAUSS, R.: Ein Heldenleben. Mengelberg. RCA VICTROLA AVM 1-2019, Apr.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Swan Lake. Previn. ANGEL SCLX 3834 (3), March.

WAGNER: Die Meistersinger. Fischer-Dieskau, Ligendza, Domingo, Jochum. DG 2713 011 (5). Bailey, Bode, Kollo, Solti. London OSA 1512 (5). Feb.

Jost CARRERAs: Operatic Recital. PHILIPS 9500 203, March.

YOLANDA MARCOULESCOU: French Songs. ORION ORS 76240, Apr.

CLAUDIA MuzIo: Edison Diamond Discs, Vol. 2. ODYSSEY Y 33793, March.

BIDU SAYiko: French Arias and Songs. ODYSSEY Y 33130, Apr.

---------------------

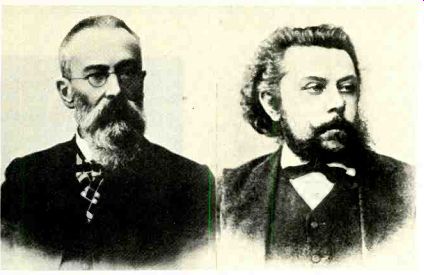

above: Rimsky-Korsakov and Mussorgsky-Enough?

HINDEMITH: Sonatas for Brass and Piano. Philadelphia Brass Ensemble members; Glenn Gould, piano. [Andrew Kazdin, prod.] COLUMBIA M2 33971, $13.98 (two discs).

Sonatas: for Horn (Mason Jones); for Bass Tuba (Abe Torchinsky); for Trumpet (Gilbert Johnson); for Alto Horn (Mason Jones); for Trombone (Henry Charles Smith).

Hindemith was well suited to the writing of duo sonatas. A master at sustaining tension by juxtaposing diverse materials, he also got great mileage out of ear-warming, open-interval chords ideal for highlighting an instrumental line. Many of these instrumental lines are ingratiating melodies whose frequent reappearances within generally transparent, neoclassic structures have a particularly pleasing effect, like the return of welcome friends.

The three-movement horn sonata of 1939 is one of Hindemith's most characteristic:

Strong, flowing themes immediately assert themselves; delicate, haunting figures in the piano settle into the background; there is a constant sense of movement. The much brasher trumpet sonata from the same year uses the solo instrument's full expressive range, from militaristic flourishes to elegiac lyricism, while the piano favors stark octaves over chordal figures. The 1941 trombone sonata is the most modern-sounding of the five works in this set, with its eye opening, wide-interval leaps from the trombone and its sometimes jarringly polytonal relationships between the piano and trombone parts.

The mellowest of these sonatas is the one for alto horn, a relatively rare instrument with a horn tone somewhat drawn toward the trombone. Opening with a lovely, rather archaic-sounding theme that moves into some strange dissonances, the sonata has an unusual slow-fast-slow-fast structure, with the second movement a typical Hindemithian march and the finale starting with a graceful piano tarantella preceded by a dialogue poem, entitled "The Posthorn," read by the performers. The most surprising work in the album is the bass-tuba sonata of 1955, the composer's last sonata. Hindemith apparently set out, improbably, to make the piece as light as possible. Whether in the rather jocular, non-thematic opening banter or in the high-low juxtapositions of the finale, the listener is almost never aware of the cumbersome nature of the solo instrument, which even gets a trill to perform.

The performances are fine. Mason Jones in particular excels in the horn sonatas, al though his tone is understandably less sure in the alto-horn work. Gilbert Johnson's trumpet comes on perhaps a bit too strong (although this may be due to the miking), while Abe Torchinsky makes the subtle tuba tunes move with amazing ease. Henry Charles Smith's careful trombone playing dulls many of Hindemith's dynamic contrasts, and the tempos here incline to deliberateness. For the most part, Glenn Gould's sharp, precise pianism and unflagging rhythmic control serve the music admirably, even when his eternal delale runs replace called-for legatos.

The performers' excellent sense of balance is well seconded by the recorded sound. R.S.B.

MENDELSSOHN: Quartet for Strings, No. 3, in D, Op. 44, No. 1. SCHUMANN: Quartet for Strings, No. 1, in A minor, Op. 41, No. 1. Budapest Quartet. ODYSSEY Y 34603, $3.98 (mono) [recorded in concert at the Library of Congress, 1959 and 1961].

Chamber-music devotees were understandably gladdened a couple of years back by Columbia's announced intention to delve into the Library of Congress' treasure trove of live performances with an ear for Budapest Quartet material suitable for issue. The initial results were disappointing: only one new disc (the Franck piano quintet and Faure's C minor Piano Quartet, on Odyssey Y 33315, December 1975), released along with a crop of reissues hardly representative of the quartet's best work. While this latest disc is a considerable improvement, I still wonder about the selection process. Since the newly issued performances, although dating from 1959 and 1961, are in less than state-of-the-art mono any way, wouldn't it have been possible to select other, earlier performances of the same works that represent the Budapest in its musical and technical prime? Nevertheless, this release has given me great musical pleasure. For one thing, the works themselves are hardly as well known as they ought to be; the Schumann A minor in particular is a complex masterpiece, with the specter of late Beethoven hanging over its pages. The Budapest plays both quartets with the kind of in-depth freedom and comprehension that comes from long experience, but the playing is technically in consistent, veering between sheer incandescence and tarnished virtuosity.

In the Schumann, for example, the solemn introduction (much akin to the opening fugue of Beethoven's Op. 131) is sheer magic, but the first movement proper is rather scraggly and unsettled. The Mendelssohn is slightly more polished (note the delicate rubato and uncanny tonal blend at the beginning of the slow movement), yet paradoxically less intense. Unlike stylistically more old-fashioned ensembles, which could get away with executant chaos, the Budapest-with its basically modern, virtuosic approach-needed its full complement of energy and finesse at all times, and by the Fifties and Sixties that standard was only intermittently attained.

That said, I prefer this Schumann to the suaver, less intense Quartetto Italiano performance (Philips) and the slicker Juilliard one ( Columbia). And with the Juilliard's kinetic Epic recording of the Mendelssohn unavailable, the only competition worth mentioning is the admirably incisive but rather bleak Fine Arts version (Concert-Disc).

H.G.

MUSSORGSKY: Boris Godunov (ed. Rimsky Korsakov).

Xenia Manna Feodor H Nurse Dmitri Shuisky Simpleton Missal Shchelxalov Boris Godunov Pimen Varlaam Police Officer Mityukh Eva Kruglikova (s) Maria Maksakova (ms) Bronislava Zlatogorova (ms) Yevgenia Verbitskaya (ms) Georgy Nelepp (t) Nikander Khanayev (t) Ivan Kozlovsky (t) V Yakushenko (t) I. Bogdanov (b) Mark Reizen (bs) Maxim Mikhailov (bs) V. Lubenchov (bs) Serge, Krasovsky (bs) Ivan Sipaev (bs)

Bolshoi Theater Chorus and Orchestra, Nicolai Golovanov, cond. RECITAL RECORDS RR 440, $21 (three discs, mono) [from Russian originals, recorded c. 1948] (available from Educational Media Associates, Box 921, Berkeley, Calif. 94701).

Xenia Ludmila Lebedeva (5) Manna: Feodor Eugenia Zareska (ms) Nurse: Hostess Lydia Romanova (ms) Dmitri Nicola, Gedda (1) Shuisky: Krushchov Andre Bielecki (t) Simpleton Wassili Pasternak (t) Boyar-in-Waiting Gustav Ustinov (t) Lavitsky Raymond Bonte (t) Shchelkalov, Rangoni Kim Borg (bs-b) Bons Godunov: Pimen Varlaam Boris Christoff (bs) Police Officer Stanislav Pieczora (bs) Chernikovsky Eugene Bousquet (bs) Choeurs Russes de Paris, Orchestre National de la Radiodiffusion Frangaise, Issay Dobrowen, cond.

SERAPHIM ID 6101, $15.92 (four discs, mono, automatic sequence) [from RCA VICTOR LHMV 6400, 1952, and CAPITOL GDR 7164, 1959].

Xenia Nadia Dobrianova (s) Mann Alexandrina Miltcheva-Nonova (ms) Feodor Rem Penkova (ms) Nurse Neli Bojkova (ms)

Hostess Dmitri Shuisky Simpleton Missail Khrushchov Boyar-in-Waiting: Lavitsky Shchelkalov Rangoni Boris Godunov, Pimen Varlaam Police Officer: Chernikovsky Mityukh Boika Kosseva (ms) Dimiter Damianov (t) bubomir Bodurov (t) Kiril Diulgherov (t) Verter Vratchovski (t) Georg' Tomov (t) Dimiter Dimitrov (t) Sabin Markov (b) Peter Bakardpev (b) Nicola Ghiuselev (bs) Assen Tchavdarov ( bs) Boyan Katsarski (bs) Peter Petrov (bs) Bodra Smyana Children's Chorus, Sofia Op era Chorus and Orchestra, Assen Naidenov, cond. HARMONIA MUNDI HMU 4-144, $31.92 (four discs, manual sequence; distributed by HNH Distributors).

Comparisons:

London, Melik-PashayeviBolshoi Col M45 696

Christoff, Cluytens, Paris Cons. Ang. SDL 3633

Ghiaurov, Karajan / Vienna Phil. Lon. OSA 1439

The simultaneous arrival of three recordings of Boris in the Rimsky recension (two of them reissues, to be sure) suggests a rush to get under the wire before the appearance of the first urtext recording, made last year in Poland ["Behind the Scenes," January 1977]. Even though it's more probably sheer coincidence, it makes a neat punctuation mark to the era in which the Rimsky rewrite job has dominated the LP lists; for a long time now, many of us have been crying, "Enough! The Rimsky version has its points, but can't we have just one recording of the original?" In fact, we should have recordings of both of Mussorgsky's versions, and perhaps also of Shostakovich's curious rescoring (a sample of which, sung in German by Theo Adam and Dresden forces, can be heard on imported Telefunken SAT 22526).

There will be ample time to debate the merits and demerits of Rimsky when the urtext recording appears; for now, let us take him for granted and consider the recorded performances, of which there have been more or less-seven in the past three decades. That "more or less" refers not only to assorted cuts and interpolations, but also to the fact that two of the recordings have been repackaged with alternate Borises: the Petrov/Melik-Pashayev with George Lon don for Columbia, and now the Pirogov/ Golovanov with Mark Reizen. Thus, six of the seven are currently available in some form. (The missing one, from Belgrade, last seen on Richmond RS 63020, was cripplingly cut and lamely conducted.

The cover of Recital Records' box for the Golovanov set reproduces a Russian Melodiya jacket designating it as a Bolshoi Theater 200th-anniversary issue, and one assumes this to be simply a dubbing of that set. Since the discographic literature known to me lists no complete Boris with Reizen, but does list one with Pirogov and an otherwise identical cast conducted by Golovanov, I presume that the Russians have merely dropped independent recordings by Reizen into that old set (once cur rent here as Period SPL 554). At any rate, the St. Basil and Death scenes here are identical to those issued years ago on Monitor MC 2016; perhaps someone with broader access to Russian material can verify the remainder of this hypothesis.

The sound, from 78-rpm originals, varies from fair to poor-sometimes very fuzzy, occasionally marred by wow, overloading, and noisy Russian surfaces, and marked during some rests by alarming multiple pre- and post-echoes; somewhat disconcertingly, the first note of the Monastery Scene has disappeared somewhere along the way. But all this is worth putting up with for several reasons. Golovanov, a high-handed conductor, is also an inspired one. He makes free with tempo modifications, but always with great authority and effect; his allargandos have as much thrust and impetus as his accelerandos.

There's no meandering here; everything points to a destination, and even the very slowest passages hold the attention.

This interpretation belongs, evidently, to an older generation than that of Melik Pashayev--not only in style, but also in the orchestral material: There are scads of percussion entries added to Rimsky's scoring, and even a celesta overlay to the harp harmonics in Boris' prayer. Though most of these excrescences are in "poor taste," the performance is simply so magisterial of its kind and era that this doesn't seem a relevant objection-one must either take it as a period piece or leave it.

One very good reason for taking it is Mark Reizen's Boris--an even, solid, and ravishingly beautiful vocal instrument used with musical precision and dramatic force.

He doesn't Chaliapinize (that tradition seems not to have been strong among Soviet basses), he doesn't snarl or chew carpets.

Like most of the greatest singers, he clearly loves his language and makes that love audible in his molding of words onto a cello-like tone that he can modulate effortlessly over the full dynamic range. Not of itself as vivid a portrait as those of Chaliapin or Christoff, Reizen's Boris fits curiously well into Golovanov's reading, the violence of the orchestral ambience glossing the tsar's inner unease.

Nearly everyone else in the cast is a positive factor, too: I will single out only Kozlovsky's poignant Simpleton-really sung, with a full dynamic range, not depending on a croaky tone quality for its pathos Bogdanov's rich-voiced Shchelkalov, and Mikhailov's firm, well-articulated Pimen.

Even the chorus soloists in the opening scene are active presences, and the chorus itself is, expectably, one of the performance's glories, even thus dimly reproduced.

The basic text used (as in all these recordings) is Rimsky's second and longer version of 1908. To this Golovanov adds the St. Basil scene (in Ippolitov-Ivanov's orchestration), making the necessary cut of the Simpleton's first appearance in the Kromy Forest scene, which here follows the death of Boris. The first Polish scene is omitted, and fairly standard cuts are made in the Monastery Scene, in Act II after the monologue (Feodor's Parrot Song), and in the second Polish scene (whereby Rangoni is completely excised). There is no libretto, no indication of which scenes are on which record sides, no information about the per formers. It would be a real benefaction if somebody could make this performance available in better sound--it certainly ranks among the more stirring operatic experiences on records.

Boris Christoff's first recording of the opera makes a fascinating contrast, for Issay Dobrowen conducts a very fine middle-of the-road performance; he does everything the way the score directs, with conviction, brilliance, and expressivity. I've always ad mired this reading, and it stands up well on rehearing after many years. Unfortunately, comparison with its last incarnation on Capitol (and, I'm sure, with its first on Victor as well) reveals that Seraphim has tam pered with the sound: A really troublesome resonance has been laid on, distancing the voices and muddying the textures. Have old recordings no constitutional rights? They really are not improved by being made to sound like bad newer recordings instead of good old ones. This one was a fine job in its day, a quarter of a century ago; if you have one of the older editions, hang on to it.

Christoff's impersonation of the three major bass roles is, of course, a tour de force-and a destructive one, for his timbre is nothing if not distinctive. On stage, doubling Boris and Varlaam is physically possible (Chaliapin did it occasionally, I believe), and good makeup would probably distract one's attention from vocal similarities--but on records, in the Kromy Forest, you can't help hearing the voice of the tsar (and, in this recording, of Shuisky as well) calling out condemnations of Boris! The Pimen-Boris doubling isn't possible in the theater, and Christoff faces the problem of differentiation by singing Pimen al most entirely in mezzo-voce-lovely but limiting. At a couple of climaxes, this clearly won't do, so he sings ou-t-and there once again is the tsar, right before our ears in another monk's clothing. These strictures apply equally to the remake with Cluytens, naturally. In general, however, the earlier version is more strongly cast: Zareska and Gedda a more mellifluous team than Lear and Uzunov, Borg splendid as both Shchelkalov and Rangoni. The White Russians of Paris aren't as cohesive in sound as the Red Russians of Moscow, but their enthusiasm is effectively mustered by Dobrowen.

Neither this recording nor the Cluytens includes the St. Basil scene (correctly, of course), but whereas Cluytens gives us every note of Rimsky's 1908 edition, Dob rowen makes the "standard" cuts in the Monastery and second Polish scenes. Seraphim reprints two-thirds of the Angel libretto (i.e., the transliterated Russian and the English, but not the Cyrillic text), with the appropriate excisions.

The latest entry, from Bulgaria, need not concern us long. Like Karajan's recording, it gives us all of Rimsky plus St. Basil, but in a stolid, provincial reading distinguished only by the presence of a few impressive voices. One of these is certainly Nicola Ghiuselev, who doubles Boris and Pimen without any perceptible effort at differentiation--or, indeed, very much characterization of either. (In fairness, I should note that he is more dramatic, and in smoother voice, on an independent disc of highlights from the opera with a different and better conductor, Harmonia Mundi HMB 130; this includes Varlaam's song and Pimen's two monologues as well as the usual solos for Boris.) But a few good voices can't salvage Naidenov's conducting, clumsy of transition and incompetent at accumulating long range momentum; at every new musical idea, the performance seems to begin all over again. Nor does the Sofia chorus match its work of 1962, when it was exported to Paris for the Cluytens recording.

Clean, rather dry sound; libretto in French only.

The upshot of all this isn't very satisfactory. For those who want Rimsky complete plus St. Basil, the choice is between Naidenov and Karajan: the one provincially dull, the other super-slickly dull. For Rimsky complete without St. Basil, there is Cluytens--an estimable but not overwhelming performance. Dobrowen is better, but makes some cuts and is not in stereo; Melik Pashayev makes similar cuts and adds St. Basil-another straightforward job. And Golovanov is strictly a supplementary choice, because of the cuts and the sound but there's no clear-cut choice among the others for it to supplement. D.H.

PUCCINI: Madama Butterfly (with operatic excerpts featuring Margaret Sheridan). Cio-Cio-San Margaret Sheridan (s) Suzuki Ida Mannanni (ms) Pinkerton Lionel Cecil (t) Goro Nello Pala (t) Sharpless Vittorio Weinberg (b) La Scala Chorus and Orchestra, Carlo Sabajno, cond.

CLUB 99 OP 1001, $20.94 (three discs, manual sequence) [from HMV/ Victor originals, recorded c. 1930] (distrib uted by German News Co.).

Operatic excerpts: PUCCINI Madama Butterfly: Ancora un passo Love Duet (with Aureliaro Penile, tenor); Che tua mad re: Un bel di. Manon Lescaut: Tu, tu, amore (with Per-tile).

VERDI: Otello: Gia nella notte densa (with Renato Li neal, tenor); Ave Maria.

GIORDANO: Andrea Chenier: Vicinoato (with Pertile).

I think it was at my first or second visit to Covent Garden that I was introduced to Margaret Sheridan, the Irish soprano (1889-1958) who had made her debut there thirty years before and-so we were always told-had gone on to become a prima donna at La Scala. She had returned to Covent Garden in 1925, a Cio-Cio-San wearing the costumes that Rosina Storchio, the first Butterfly, had worn, and then sang there for five seasons. Harold Rosenthal in his history describes her as "firmly established at La Scala," and John Steane as "the toast of La Scala." The annals of that house don't exactly bear this out. In 1922 she made her Scala de but in La Wally; in 1923 she was Candida in Respighi's Belfagor; in the 1923-24 season, Anna Maria in Riccitelli's I Compagnacci and Maddalena in three performances of Andrea Chenier. Of course, the Scala isn't all the world, or even the whole of Italian opera. Eva Turner sang only Freia and Sieg linde there, and won fame for her great Turandot in other houses.

But in her day, it is plain, Sheridan wasn't quite deemed among the first flight of Butterflies. She has a strong shining voice, which can rise purely to fill a long, powerful line without strain and without resorting to that kind of pressure which (as, say, in Renata Scotto's climaxes) imparts a squealy stridency to the tone. But she is not a particularly imaginative or delicate singer. Her Cio-Cio-San lacks charm and fine detail. (When she first sang it at Covent Garden she was eclipsed by Rethberg, and when she next sang it there, five years later, by Maggie Teyte.) This complete Butterfly is a "plum label" set; by color and by a lower price, HMV thus distinguished its more modest offerings from those in the red-seal celebrity series.

Club 99 provides no date. This Butterfly is first listed in the 1931 HMV catalog and so can be assigned to 1930-the year of Sheridan's last Covent Garden season, six years after her last Scala appearance. The recording is surprisingly good. What I found my self listening to with the greatest interest was the orchestral playing. Some of Sabajno's tempos, particularly toward the start, are brisk to the point of seeming perfunctory, but I doubt whether there is on disc a more beautifully handled dawn prelude to Act II, Part 2 than he conducts. De spite the 1930 recording one hears the expressive, eloquent colors of the Scala woodwind. (Later, the clarinets that accompany Butterfly's quiet questions to Suzuki are heartbreaking.) Puccini notated his birdsong metrically; sometimes the player of the birdcalls comes in so strictly on the beats that the result is ridiculous-birds drilled to warble a dawn chorus in 4/4! Sometimes the player is just vague. But this player, without ever seeming unnatural, shows exactly how the composer evidently meant his touches of pretty warbling to fall.

It is also very good to hear the portamento of the Scala strings. String players today have not learned about portamento or learned only to avoid it. But all the re corded evidence shows that in the first decades of this century it was taken for granted, and that eschewing it in music of that period is simply bad style.

Who was Lionel (or Lionello) Cecil? What did he do besides recording this Butterfly and, with Mercedes Capsir, a Traviata for Columbia? He is a tenor of a kind we could do with today, obviously very well schooled, even, with a true tenor ring at the top, and he is an aristocratic stylist.

Vittorio Weinberg-the only Scala Wein berg I can trace sang the Theban Slave in Pizzetti's Fedra in 1939-makes a Sharpless of uncommon courtesy, dignity, and feeling. Ida Mannarini and Nello Palai often turned up in small Scala roles of the time, and their Suzuki and Goro bear witness to the excellence of Scala comprimarios in the Toscanini years.

Obviously this is a set only for Sheridan-lovers, Irish operatic patriots, Puccini specialists, and anyone with a particular concern about Thirties performance practice.

It is not a great performance from the past, but a run-of-the-mill performance with some interesting features. The Butterfly I recommend to anyone who says "Which version should I buy?" is still the Toti dal Monte/Gigli set of 1940 (Seraphim IB 6059), which as a whole has not--except in point of sonics--been surpassed by later versions.

(And that despite a heroine less beautiful of voice than some of her successors.) The titles collected on the final sides of the set are from "red label" HMV discs, re corded 1928-30. Because Sheridan was an uneven singer, there are some touches in the Butterfly excerpts that are preferable to the corresponding passages in the complete set, and some that are not. In the Manon Lescaut duet, Pertile's cry of "O tentatrice" is stirring. Renato Zanelli was a famous Otello, but his share of the love duet, as John Steane says bluntly, is "without distinction of phrasing"; so is Sheridan's share. However, there is a distinctive, dignified timbre to Zanelli's voice that I like very much. A.P.

RAVEL: Le Tombeau de Couperin. STRAVINSKY: Petrushka: Three Movements. Alexis Weissenberg, piano. CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CS 2114, $6.98.

RAVEL: Gaspard de la nuit; Serenade grotesque.

STRAVINSKY: Petrushka: Three Movements. Les cinq doigts. Valse pour les enfants. Idil Biret, piano. [Ilhan Mimaroglu, prod.] FINNADAR SR 9013, $6.98.

It is intriguing that Ravel never thought to publish his first piano piece, the Serenade grotesque (1893), which offers considerably more interest than certain later vignettes, such as the two A la maniere de pieces, that are fairly well known. The music shows Ravel in a fairly impish, bad-boy mood, obsessively repeating accentuated dissonances and jerky rhythmic figures. And yet these rather jolting grotesqueries alternate with smoother, often Hispanic flavored passages that foreshadow even more clearly the Ravel to come.

Turkish pianist Idil Biret offers the first recording of the Serenade grotesque, al though another version-by Arbie Orenstein, who discovered the piece-will soon be released on Musical Heritage along with some other previously unrecorded Ravel.

Margaret Sheridan Not quite a first-flight Butterfly

Biret's interpretation has many merits:

Hers is a nervous style given to sudden swells and jarring accentuations, and it works well enough for the Serenade. Yet one might wish for a bit more relaxation and a bit more flow to hold the episodes together.

Biret's Gaspard de la nuit as well. The pianism impresses there is a great deal of very nice shading, and the tricky balances between the music's component parts are skillfully maintained. But this same balance is sometimes destroyed by Biret's impetuousness, with beautiful passagework suddenly giving way to outbursts more spat out than articulated. And I have never heard a performance of the second movement in which the repeated B flat becomes so oppressive. Perhaps Biret intended it this way, but I doubt Ravel did. In her pedaling as well, Biret occasionally indulges in excesses that go against the music's grain.

Speaking of bad pedaling, Alexis Weissenberg does things in the Tombeau de Couperin that one would hardly expect from a professional pianist. What led him to slur together the lovely baroque filigrees in Ravel's tribute to the Couperin era is beyond me-it is all horribly unidiomatic.

The wistful little "Fugue," which is ripped through and pedal-blurred almost out of existence, suffers the most; but none of the six movements escapes unharmed. Add to this a cramped, unimaginative interpretation with almost no rhythmic life, and I find very little to recommend this contribution to the crowded Ravel discography.

Even though Stravinsky gave the piano a major role in Petrushka, the solo-piano "Three Movements" he arranged in 1921 for Arthur Rubinstein simply screams out for the dazzling orchestral sonorities. Neither Biret nor Weissenberg can get around this, but both display jaw-dropping virtuosity. If Weissenberg is a step ahead in this department. Biret surpasses him in maintaining the independence of the juxtaposed material in the final "Shrovetide Fair" movement. Interpretively, my favorite performance of the "Three Movements" is Beveridge Webster's in the lamented Dover "Piano Music of Stravinsky" set, although his technical prowess does not match Biret's or Weissenberg's. But Webster also got brighter, cleaner sound.

Finnadar adds to the Petrushku movements two less popular Stravinsky piano pieces, Les cinq doigts (The Five Fingers, 1921) and %/case pour les enfants (Waltz for Children, 1917), the latter lasting less than a minute. Biret performs these vignettes convincingly enough, but her efforts are some what scuttled by an out-of-tune piano, also noticeable in Gaspard.

R.S.B REGER: Sonata for Clarinet and Piano. Op. 107. For a review, see page 84

ROSSINI: II Turco in Italia.

Fiorillo Zelda Don Narciso Albazar Prosdocimo Sehm Don Geronio Maria Callas (s) Jolanda Gardino (ms) Nicola' Gedda (t) Piero de Palma (t) Mariano Stabile (b) Nicola Rossi-Lemeni (bs) Franco Calabrese (bs) La Scala Chorus and Orchestra, Gianandrea Gavazzeni, cond. SERAPHIM IB 6095, $7.96 (two discs, mono, automatic sequence) [from ANGEL 5sL 3535, recorded September 1954].

If we exclude early appearances in Boc The Land of Smiles, and Der Bettel student, Fiorilla in II Turco was the first of the two comic roles that Callas essayed.

Rome had heard her only as Turandot, Kundry, Isolde, and Aida when she sang Fiorilla there in 1950. Four years later, in September 1954, she recorded the opera, in anticipation of the Scala production, by Zeffirelli, which followed in April 1955 (a month after the famous Visconti Sonnamhula, a month before the famous Visconti "I'rtiviata). Callas, Stabile as the polished and witty poet, Calabrese as the buffo husband, and the conductor Gavazzeni were common to all three performances.

The Scala production was by all ac counts a deliciously high-spirited occasion:

Zeffirelli has recalled some of the ways in which the tragedienne was transformed into a comedienne. The recorded performance, however, lacks hilarity. Although Gavazzeni gets bright, pointed playing from the Scala instrumentalists, there is not much wit or gaiety in his reading. Callas doesn't bubble; the sly sparkle and merriment of the Rosina she tackled in 1956, and recorded a year later, were still to come. But she is in secure voice, and she makes much of the words. Stabile, Rossi-Lemeni. and Calabrese are good, too. Gedda, if not quite polished (Valleti did the Rome and Milan stage performances), is acceptable; in any case the part is tiny.

I think it's Gavazzeni's sobriety that keeps me from being more enthusiastic about the set. I love the opera, and wish there were more verve in its performance.

All the same. the reissue is welcome; every thing that Callas and that Stabile did de serves to slay in print. The set has been re- cut, on four sides instead of five; the sound is fresh and clean. A.P.

SCARLATTI, A.: Stabat Mater. Mirella Freni, soprano, Teresa Berganza, mezzo; Andre lsoir, organ; Paul Kuentz Chamber Orchestra, Charles Mackerras, cond. [Gerd Ploebsch, prod.] AHCHIV 2533 324, $7.98. Tape: C I310 324, $7.98.

Alessandro Scarlatti's Stabat Mater, known to have been the model for Pergolesi's famous setting of the thirteenth-century poem, is an unusual work by a great master, but some questions must be asked even before starting the turntable. Simply put: What are we about to hear? The notes say that the Stabat Mater was edited by Felice Boghen, yet that quondam piano pedagogue was not an editor, but a notoriously high-handed arranger. The notes further state that the edition used for the recording was "corrected" from a manuscript pre served in Florence but fail to tell us whether this is a holograph or a copy. Why "correct" an unreliable edition when there is an extant manuscript, and who did the corrections? Let us suppose, however, that we have a reasonably accurate musical text: now we must contend with the extraordinary shape of the great medieval poem. It consists of twenty Latin stanzas of three lines, more than half of the sixty lines containing three, or sometimes even two words-how can such a text be set to music? Scarlatti did not resort to the usual endless repetition of words, composing instead a string of cameos of (if you pardon the anachronism) Webernesque brevity, and while many of them are very beautiful, he could no more overcome the severe limitations of the frame than could Pergolesi; there was simply no room for through-composed structure. After about halfway along, a certain sameness descends on the listener. This, incidentally, may have prompted Scarlatti to become increasingly bold and chromatic as he proceeded. It is likely, of course, that performances at the private devotions of the Neapolitan brotherhood of the Cavalieri della Vergine dei dolori were not continuous, but "troped" with prayers or even with some other music.

The Archiv performance shows stylistic uncertainty, which is understandable be cause this work is not within any of the familiar categories of church music. Teresa Berganza knows what she is singing and enunciates and phrases intelligently, but her fine voice shows extremely contrasting color regions: when she descends low the timbre becomes very dark. Mirella Freni seems to be out of her bailiwick: she sings as well as she can but without communicative conviction-few words are understandable. Also, her frequent trills lack definition. Both singers are a little too close to the microphone, which makes Freni's high notes a bit shrill.

There is more trouble with the accompaniment. The "orchestra" consists of eight violins and continuo (cello, double bass, and organ). Nothing wrong with that: The fraternity that commissioned the work had modest means. This complement of instruments would have been satisfactory in a small chapel, but recorded in a church the tiny ensemble is thin, pale, insubstantial.

The typical church echo, though not excessive, is still disturbing because of the short sentences and frequent rests of the music.

The organ continuo, "improvised at the performance," is far too busy, diverting attention from the work itself. Most seventeenth- and eighteenth-century theorists enjoined the continuo player not to compete with the composer, yet Andre Isoir does just that, toying with thematic bits and inserting imitations; some of the numbers sound as if the orchestra contained wood winds.

Nevertheless, it is good to have this profoundly serious work available, and a fair amount of it does come across. I must add a remark about Archiv's curious English translation of Jacopone da Todi's poem.

The German and French translations are faithful within the requirements of versification, but the English version, though equally well handled, departs fundamentally from the sense of the Latin in the second half. It is to the "Sancta Mater" that the prayers are directed; the English version, by addressing every petition to Christ, excises Mary's role completely and changes the thrust of this tender hymn. Was this due to Protestant aversion to Marian worship? At any rate, it is unusual for Archiv to relax its commendable care for scholarly accuracy. P.H.L. B. H.

SCHOENBERG: Gurre-Lieder. Tove Wood-Dove Waldemar Klaus-Narr Peasant Speaker Jeannette Vreeland (s) Rose Bampton (ms) Paul Althouse (t) Robert Betts (t) Abrasha Rabofsky (bs) Benjamin de Loache (spkr) Princeton Glee Club, Fortnightly Club, Mendelssohn Club of Philadelphia, Philadelphia Orchestra, Leopold Stokowski, cond. RCA VICTROLA AVM 2-2017, $7.98 (two discs,

-----

Update: Nielsen, Berlioz

Abram Chipman's enthusiastic February review of Herbert Blomstedt's Nielsen symphonies on Seraphim left open the question of eventual issue of some material included in the British release. We are pleased to report that the three concertos and the early Symphonic Rhapsody are now scheduled for July release as Seraphim SIB 6106: that two-disc set will complete domestic issue of the Nielsen material.

Although Leonard Bernstein's Berlioz Requiem was scheduled to he among Columbia's first compatible-quad releases, it was not in fact so issued, as stated in our April review. This explains the decoding oddities reported in the technical note; as reported, however, in SQ playback the Columbia stereo discs offer "a powerful, sweeping opulent sound that fairly overwhelms the listener at times."

----------

mono, automatic sequence) [from RCA VicTOR M 127 and LCT 6012, recorded in concert, April 11, 1932].

Victor's courage in undertaking to record this mammoth work "live" at its American premiere-and during the depths of the Great Depression, at that-deserves some fond recollection; for two decades this served as virtually the only way to hear the piece. Now we are a quarter-century further on, with three stereo recordings in the catalogs, and the question has to be raised:

Has the recording any remaining utility other than archival, as documentation of an important event in the history of American musical performance? The answer, I am afraid, is "no,- for what survives on these discs can only be a pale echo of what filled Philadelphia's Metropolitan Opera House back in 1932. The sound is muffled and muddy, the dynamics are ruthlessly compressed. Here and there, in lightly scored passages such as the Klaus-Narr episode, it is possible to hear some fabulously lively and accurate playing from the orchestra. The chorus is distant and makes little impact. In terms of balance, the soloists are pretty well treated, but only one of them-the young Rose Bampton--is particularly distinguished.

Paul Althouse and Jeannette Vreeland are capable routine singers working at their outer limits. Abrasha Rabofsky has some rough moments, and Robert Belts speaks, rather than sings, most of his part. Both Rabofsky and the speaker, Benjamin de Loache. have some trouble keeping with the orchestra. If Flagstad and Melchior had been the soloists, we would listen avidly to these records even were the sound worse than it is-but there's nothing in the vocalism here that hasn't been done as well or better since.

As I've mentioned, the orchestral playing seems quite spectacular when it can be made out, and Stokowski certainly makes the piece flow along with a firm hand though sometimes a characteristically free interpretation of the tempo markings (Waldemar's "Mit Toves Stimme.- marked "not too slowly" with a metronome of 72, is taken at about 48, which sounds precisely "too slow" and makes for poor Mr. Althouse some problems he definitely doesn't need). Because of the dynamic compression, one can hardly even infer much about the overall shape of the performance in terms of scaling climaxes and the like.

According to RCA, this issue is based on the same tape transfer that served as source material for the mid-1950s LP issue in the "Treasury" series, though some fresh effort was made to improve the sound. The 78 surfaces grind away fairly quietly throughout (occasionally more disturbingly), and there is one overly hasty splice (at No. 69 in Part I). According to the liner notes, all three performances of the run were recorded, but my RCA informant says there is no trace in the files of the Friday afternoon concert presumably a trial run that was not even noted in the books. The Saturday performance was taken on the 33-rpm standard-groove long-playing records that Victor experimented with at this time, and was is sued as LM 127 (Stokowski collectors note: Your collection is not complete until you have that one!). The present recording is of the third performance, on Monday evening.

The original 78 and 33 issues included introductory talks by Stokowski (different ones, of four and twelve minutes, respectively), but these are omitted here. For some reason, there is a noisy ovation at the start of Side 1, but the applause at the end has been cut off. The double sleeve includes a complete text and translation. D.H.

SCHUMANN: Quartet for Strings, No. 1-See Mendelssohn. Quartet, No. 3.

Stravinsky: Petrushka: Three Move ments-See Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin.

VERDI: Macbeth. Lady Macbeth Gentlewoman Second Apparition Third Apparition Macdutt Malcolm Servant to Macbeth Macbeth Murderer Herald Banquo First Apparition Doctor Fiorenza Cossotto (ms) Maria Borgato (s) Sara Grossman (s) Timothy Sprackling (boys) Jose Carreras (t) Giuliano Bernardi (t) Leslie Fyson (t) Sherrill Wines (b) John Noble (b) Neilson Taylor (b) Ruggero Raimondi (bs) Christopher Keyte (bs) Carlo del Bosco (bs) Ambrosian Opera Chorus, New Philharmonia Orchestra, Riccardo Muti, cond. [John Mor dler, prod.] ANGEL SCLX 3833, $23.98 (three discs, automatic sequence). Tape: IFO 4X3S 3833, $23.98.

Comparisons:

Rysanek, Warren, Leinsdorf Victr. VICS 6121 Nilsson, Taddei, Schippers Lon. OSA 1380 Verrett. Cappuccilli, Abbado DO 2709 082 This is the second Macbeth to be released within five months, and will presumably end recorded attention to the opera for a while. For some comparative commentary on the versions now available, I refer read ers to my review of the DG edition in the January issue.

The present recording, like the Gardelli/ London (OSA 13102) and the Abbado/DG, is of the complete 1865 revision, including all repeats and the full ballet sequence. The 1847 death of Macbeth (the arioso "Mal per me"), often inserted in performances of the 1865 score (as in the Leinsdorf/Victrola and Abbado/DG recordings), is omitted, but is included on a separate band, together with 1847 arias for the two principals that have not been previously recorded.

I find this a satisfying performance, and one that has sounded more persuasive on repeated hearing-the reverse of my experience with DC's effort. This has been largely a matter of adjustment to the approaches of the conductor, Riccardo Muti, and the Lady Macbeth, Fiorenza Cossotto. Muti's previ ous recordings have shown him to be an authoritative young Verdi conductor. He has a particular penchant for the driving, forceful side of the composer's writing, and for sudden accelerations in strettolike sections (as at the phi mosso, "Guerra! guerra!," in the "Su! del Nilo" ensemble of Aida-one I'm not used to yet). But he never sounds merely excitable, and unlike some of the modern Verdi conductors who share some of his qualities (I think of Mehta and Le vine, for instance) he seems to have a sure feel for the shape of a singing line, and for the moods of some of the more mysterious and poetic pages.

In this reading, a few of his quicknesses still bother me-for instances, the entire prelude clips right along, missing some of the weight its more portentous moments can have, and the witches' allegro brillante in the first scene ("Le sorelle vagabonde") expresses rather more the wish to get the show off to a bang-bang start than any evi dent impulses of the sisters in question. But other similar moments, which initially struck me as rushed, have on rehearing come to seem quite just and genuinely ex citing; examples are the presto at Lady Macbeth's "Vien! vien altrove, ogni sos petto" (final section of the scene just after the murder of Duncan), or the allegro agitato at Macduff's "Orrore! orrore!" a few pages later.

The instances where Muti takes tempos noticeably more deliberate than his customary choices seem to reflect collaborations with Cossotto to achieve her best effect in solo numbers-the bars setting up the andantino for "Vieni, t'affretta" (at rehearsal No. 19), where he effects a big slow down, and the Brindisi in the Banquet Scene, which is markedly deliberate to start with, and accorded definite ritards at the ends of verses. Since both these moments are highly successful in performance, the judgments are self-justified. On the whole, it is a somewhat quick, light-toned reading, emphatic and quite brilliantly executed by orchestra and chorus. The ballet has more of the flavor of a divertissement than it does in other readings, with the relationship to the incidental dances of Aida very obvious.

The two principal singers take over the performance rather more than those of other versions (except, perhaps, for the Leinsdorf /Met performance), and since this certainly isn't traceable to conductorial flabbiness, I count it a good thing. Cossotto is the first Italian to record her role, and while I wouldn't at all argue that Italians invariably sing Verdi better (or even more knowledgeably) than outlanders, in this case the difference really shows-for all the peculiarities of her method and the inappropriateness of her timbre to some of her recorded assignments (Ulrica, for in stance), she has become an expert and commanding artist.

Cossotto's singing has in it more of the chiaro than of the oscuro, and, particularly since she is a mezzo essaying a soprano role, this makes for some of that wiry, shallow-bright tone toward the top recalled from such singers as Bianca Scacciati (or, in her more frazzled moments, Rena t a Scotto), where the "bite into the tone" be comes a nip on the ear. There are a couple of nasty sustained B naturals here, and though she squeezes out the infamous pp D flat in the Gran Scena del Sonnambulismo, I wish I hadn't heard it.

On the other hand, her method makes for real firmness and lucidity. It is a joy to hear the language so specifically treated, tb hear the trills (in a very difficult low tessitura) of the first aria beat with a true, precise bra vura, to hear the rhythms launched with such grandezza. Phrases are purposefully conceived, then really finished off. She cleverly plays off registral textures for their expressive effect-nowhere more so than in the Brindisi, where her exact little strokes into chest on the F naturals combine with detailed embellishment, precise attacks, literal observance of note and rest values, and the held-back tempo to create completely the piece's air of calculated celebration.

The Sleepwalking Scene has fine atmosphere and detail, with Cossotto making much more of spots like "Orsb, t'affretta" than other good artists have. There are places where Nilsson, Rysanek, or even Verrett can be preferred for sheer vocal command, but I think no one has illuminated so much of the role (at least its audible aspects) since Callas.

Milnes's Macbeth does not quite stand out from the field in these same ways, but it is a performance of stature-he is scrupulous with respect to the musical and interpretive suggestions of the score, and his voice is closer in calibration to the role's demands than those of Fischer-Dieskau (with Gardelli) and Cappuccilli, his recent competitors in the uncut recordings. It is true that the voice has lost some of its freshness and openness-the poise and brilliance with which he sang his early Valentins, Tonios, and Yeletskys is no longer quite there. The timbre has become a bit gritty and gray, the handling of the passaggio rougher and lower in the voice.

However, this is still a powerful, wide-ranged instrument, and the technique has its points of expertise as well as its problems: Milnes possesses a far broader range of color and dynamics than does Cappuccilli, and more command of sustained singing line. There is also a basic vitality and energy in his singing that keeps it above dullness. His work can be externalized and general (while he is usually interesting and sometimes exciting, he is seldom moving), but its physical commitment is never in doubt.

Here, his best work is in the murder scene with Lady Macbeth and in the Banquet Scene, where he shows a welcome dramatic involvement and spontaneity: His en trance at "Sangue a me" in the Act II finale, for example, really captures the moment's feeling. The arias are less persuasive. The Dagger Soliloquy is, in its way, expert very completely observed, vocally under firm control--but it isn't gripping, while the "Pieta, rispetto" has a sort of generalized emotionality about it that is Italian Bari tone Aria without being Macbeth. All told, I imagine I shall remain attached to the performances of Warren and Taddei in this role, though Milnes's is, I think, easily the choice among the more recent versions.

Jose Carreras is a little light of timbre for Macduff, but sings the aria with clean, bright tone and flowing line. Ruggero Rai mondi, however, is in doleful shape as Ban quo-a few impressive tones toward the top, but stiff, crude sound elsewhere, practically no fluidity to the phrasing, and in sufficient bottom for even the modest demands of the part. The small roles are taken adequately, if anonymously.

The two 1847 arias included have some documentary value, if not much else. Lady Macbeth's "Trionfai," later replaced by the fine "La luce longue," is a trite, if energetic, aria in the worst showpiece tradition. Un fortunately, it also lies much higher than

Cossotto can comfortably accommodate, and she sings it shrilly. Macbeth's "Vada in fiamme" is a bit better, being at least a de cent standard vendetta piece that would not be out of place in, say, I Masnadieri, but a far weaker conclusion to the second witches' scene than the duet that replaced it. Milnes sings it sturdily but a bit clumsily, so that it makes a clomping effect. "MW per me," of course, is a different matter-a sensitive setting of a moment that is absolutely vital from the dramatic standpoint. It belongs in the score, but the decision to re main consistent to the revised rendition is certainly understandable.

I was not happy with the sound of this recording. To begin with, my pressings arc afflicted with a strong persistent pre-echo.

But I also found many of the bass-heavy passages (especially those involving percussion and low brass) productive of only a large, rumbly noise, ample but unmusical, and the dynamic range simply too wide for home consumption-the scene between the Doctor and Gentlewoman and the mezzo-voce sections of the "Ora di morte" duet pretty well vanish at a setting that can accommodate the tuttis. The accompanying booklet is literate and attractive, with well-selected notes and illustrations. C.L.O.

VILLA-LOBOS: Piano Works. Roberto Szidor, piano. [Cord Garben and Rainer Brock, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 634, $7.98.

A Fianderia; Rudepoema; Saudades das selves brasi leiras; New York Skyline; Carnaval das chances brasi leiras (with Richard Metzler, piano); Lenda do caboclo;

Suite floral (Three Pieces), Op. 97.

Roberto Szidon is one of the younger generation of knock-'em-down, drag-'em-out keyboard athletes-as demonstrated earlier in his 1970 Gershwin and MacDowell concertos, 1971 Ives sonatas, and 1974 Liszt rhapsodies. But while he was partly trained in this country and concertizes most actively in Europe, he is Brazilian-born and hence an apt choice to follow Nelson Freire and Cristina Ortiz in paying tribute to the piano music of their great compatriot Heitor Villa-Lobos.

Expectedly for such a virtuoso technician, Szidon features the notoriously de manding, large-scaled, dramatically vivid musical portrait of Arthur Rubinstein in his uninhibited youth, the Rudepoema of 1921-26. But while Szidon's is an exciting and at times overwhelmingly thunderous performance, I find it no match for the 1975 Freire/Telefunken version in tautness and lucidity. He is similarly unlucky in his com petition in the more romantic Lenda do ca boclo, the atmosphere of which was evoked more hauntingly by Ortiz for Angel. Szidon also is somewhat handicapped throughout by the tonal qualities of his piano, the brittleness of which is italicized by the dry acoustical ambience of DG's brightly clean but hard recording.

Yet there are enticing compensations in the rest of the Program's provision of works not otherwise currently available on records (the innocently impressionistic early Floral Suite and the two lyrical pieces in the Yearnings after the Brazilian Jungles) or probable recorded firsts (the florid Spinning Girl showpiece; the 1957 piano versions of the 1940 "symphonic milli metrization" of the New York Skyline; and the Children's Carnival of 1919-20, the eighth piece of which calls for a second pair of hands, here those of Richard Metzler).

For all his slam-bang, slapdash moments, Szidon obviously revels in this music's wide variety of mood and technical fascinations-and he makes his own relish contagious. R.D.D.

WEILL: Vocal and Instrumental Works. For an essay review, see page 77.

WOLF-FERRARI: II Segreto di Susanna.

Susanna Maria Chiara (s) Gil Bernd Weikl (b) Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, Lamberto Gardelli, cond. [Christopher Raeburn, prod.] LONDON OSA 1161, $6.98.

I'm glad that 1976 didn't pass with the centenary of Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari's birth quite unobserved by the record companies.

His music (except in the sensational I Gioielli della Madonna) may be slender, but it is captivating.

Half-German, half-Italian, he made his name in Munich (II Segreto di Susanna was the third of his operas to have its premiere there). Rheinberger trained him; study un der that composer of sound, thorough organ sonatas seems an odd preparation for light, sparkling operatic comedies, but it may ac count for the excellence of Wolf-Ferrari's musical craftsmanship; he is one of the most delicate and precise of composers.

Among his musical ancestors we can discern, on the German side, Mozart and Schubert and, on the Italian, Rossini (for high spirited invention) and Bellini (for purity of lyric melody). I'm not placing him on their level, only suggesting that qualities they have, he shares. And, in the words of The Record Guide, "Wolf-Ferrari wrote for the voice with a Mozartean delicacy unknown to the rest of the modern Italian school." Today, this opera would have to carry a warning from the surgeon general. Susanna's secret is that she smokes. Her husband smells tobacco smoke in the house and suspects her of receiving a lover in his absence; she, delightful innocent, is to the last unaware of that. ("I have to do some thing to pass the time while you're at your club." "Shameless woman, I'll tell your mother about you." "Oh, good God, for all I know, she too. . .") At last Susanna's little "perfumed vice" is revealed, and the re lieved Gil joins her in a cigarette.

Between 1912 and 1927 four of Wolf-Ferrari's operas--Le Donne curiose, II Segreto, L'Amore medico, and I Gioielli--were taken up by the Met. None survived more than two seasons except 11 Segreto. In 1912-13, with Farrar and Scotti, it was paired with Pog or played as a curtain-raiser to La Boheme. In 1913-14 it formed a Wolf-Ferrari double bill with the two-act L'Amore medico. It was revived 1920-22, with Bori and Scotti, as curtain-raiser or afterpiece. Farrar recorded Susanna's first aria and (with Amato) the duet "II dolce idillio"; Alda, Muzio, and Bori all recorded Susanna's "Oh gioia, la nube leggera." Meanwhile at Covent Garden for several seasons the regular Gil was Sammarco, with various, less celebrated Susannas.

Glyndebourne played the opera in 1958 as a curtain-raiser to Ariaclne, and in 1960 with La Voix humaine and Busoni's Arlec chino. But nowadays, one-acters seem hard to place. Lu Boheme, Salome, and Ariudne are deemed Abendf Coy goes with Pug: II Trittico is kept as a triptych. Yet any company with some of, say, Dido, Oedipus Rex, L'Education manquee, Erwartung, La Voix humaine, L'Enfant et les sortileges, Bluebeurd's Castle, and Down in the Valley in its repertory might well consider adding Susanna's Secret. It's as lighthearted and as easy to stage as The Telephone, and musically far more distinguished. And unless opera companies maintain a stock of one acters, from which to deal various triple bills, a good deal of excellent music is likely to remain unperformed. Ballet companies have the right idea.

The London performance is delightful.

Maria Chiara is limpid and lyrical. Bernd Weikl, adding Italian to his recorded languages (Russian, French, German), sings with style and spirit. It's a gentle and intimate account of the piece. Even when the duet is marked to mount to a fortissimo, the singers don't really sing particularly loudly.

In the theater, I think I would want a little more dash and brio, and a little more bluster (elegantly polished bluster, of course) and ferocity from Gil when he bursts unexpectedly into the smoke-filled room. These singers don't have quite the piquancy or wit that the best of their predecessors brought to the roles. But they do have charm; they are sweet and tender; and they make very pleasing sounds.

Lamberto Gardelli's conducting is delicate, buoyant, and refined, as is apparent from the start of the "overture in min iature-on four themes" (carefully numbered in the score, so that with a smile we can appreciate the composer's skill in combining them). The Covent Garden players are excellent. The recording is carefully balanced; the perspective of Susanna's off stage piano-playing and Gil's on-stage com mentary is just right; there are one or two Ping-Pongy moments (a stage direction that justifies the effect, "Gil paces up and down," has been omitted from the album libretto).

Omar Godknow, as the mute servant Sante, also gets star billing. He is a Deccai London artist whose dame often springs to the lips of Christopher Raeburn, the producer of this set; he made his debut, if I re member rightly, as Klaus, the mute slave in Die Ent fiihrung. To II Segreto his contribution is a single, well-timed "Ffff," as he puffs out the candle just before the curtain falls.

I understand why II Segreto was chosen for the centenary recording-Wolf-Ferrari's only one-acter, his best-known opera, and only two singers needed. Nevertheless, it has been recorded at least twice before, and not badly, even if those versions are now some twenty years old. I welcome this set. 1 would also welcome choice excerpts from L'Amore medico, from Le Donne curiose, and above all from II Campiello--delectable operas all. A.P.

========

Recitals and Misc.

KEITH BRYAN AND KAREN KEYS: American Works for Flute and Piano. Keith Bryan, flute; Karen Keys, piano. [Giveon and Marion Cornfield, prod.] ORION ORS 76242, $7.98.

BURTOIC Sonatina. COPLAND: Duo.

PISTON: Sonata. VAN VACTOR: Sonatina.

The combined sonorities of the flute and piano have appealed to a fair number of con temporary composers-not just in a melody--accompaniment sense but in a very complete way, in which the two opposing timbres have inspired subtle, line-against-line clashes and various tone combinations particularly in tune with twentieth-century musical aesthetics.

The late Walter Piston's 1930 flute sonata is a masterpiece, blending in unique fashion a neoclassical structure and forward movement, a romantic lyricism, an impressionistic use of harmonic color, and a very Pistonian brand of acidity. The instruments continually weave their way through paths traced by the other. In the second movement, for instance, a rather morose flute theme keeps bumping into parts of the piano's hypnotically persistent octave filigree, only to reach ephemeral consonance a few seconds later. (A well-known flutist with whom I once played through this work said that he found these clashes dissonance for dissonance's sake, but it seems to me they are an essential part of the movement's striking structure of dialectic and resolution.) Copland's three-movement Duo, com posed in 1971 in memory of William Kincaid. for many years the first-chair flutist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, alternates an elegiac character (as in the opening flute solo and the entire second movement) with such familiar Copland devices as zigzag rhythms and wide-space, angular harmonies. The 1945 sonatina by David van Vactor--the only flutist among these four composers-often reminded me, in a very positive way, of Hindemith (whose 1936 sonata is another classic in the flute/piano repertory). Because Eldin Burton's 1948 sonatina falls back on a rather Faure-esque separation of instrumental roles, it is much the least interesting work here.

Keith Bryan and Karen Keys perform all four works with exceptionally good timbre balance and a good deal of spirit. The Copland Duo comes off best, but Columbia has an outstanding version by the late Elaine Shaffer, with the composer at the piano (M 32737). The performance of the Pis ton sonata is a bit glib, with the dryness of the first movement somewhat obscuring its moody, pastoral quality and the finale short on excitement-Bryan is a bit imprecise in the difficult passagework at the end. But the renditions of this generally interesting repertoire are more than satisfactory. Excel lent sound quality also helps-for once the piano has been given equal attention in the recorded balance. R.S.B.

PAUL JACOBS: Piano Etudes. Paul Jacobs, piano. [Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] NONESUCH H 71334, $3.96.

Bound': Etudes (3). Op. 18. MOM: Sechs kurze Stdcke zur Ptlege des polyphonen Spiels. MESSIASN: Ouatre Etudes de rhythme. STRAVINSKY: Four Etudes, Op. 7.

The listings above, like the Nonesuch jacket, give the composers' names in alpha betical order, but the chronology of the works is Stravinsky, Bartok, Busoni, Mes siaen, and it all sounds better that way.

Stravinsky's Four Etudes (1908) are studies in poly-rhythms, in wit and dry brilliance, and in rather delicate nuances of harmony, a la Scriabin. The motoric drive of the Socre was as yet unrevealed, but that is the point of departure for Bartok's three Op. 18 Etudes, composed in 1918; Bart6k also takes a sidelong glance or two at Debussian coloristic writing for the piano and at Schoenberg's chords in fourths.

Busoni's Six Short Pieces for the Development of Polyphonic Playing, although written as late as 1922, stem from nineteenth-century concepts of transcendental virtuosity. But they are very much to the point, full of fiendish ingenuity in the key board problems they posit, and admirably calculated to make one sit up and take notice of the hands on that keyboard. Oddly, the last study of the six is an almost literal transcription of the chorale sung by the two

Armed Men in the trials by fire and water of The Magic Flute.

Messiaen's Four Studies in Rhythm is the longest and most pretentious piece on the disc. In his liner notes, Paul Jacobs pays much more attention to the serial complexities of the music than to any other aspect of it, and, as is often the case with Messiaen, the serialism maunders on until one is ready to scream in protest. But there are wonderful things here, too-tunes from New Guinea and India, drum and bell and bird sounds, and a rhapsodic grandeur over-all that gives the work a more notable shape than all the serialism in the world.

Jacobs is one of that new breed of pianists who are colossal virtuosos and first rate intellects as well. His playing is magnificent, his prose is warm and illuminating, and the two aspects of his musical personality come together in interpretations that are as sensitive, profound, and convincing as one could wish. A.F.

CouN TILNEY: Fantasias. Colin Tilney, clavi chord. [Heinz Wildhagen and Andreas Hol schneider, prod.] ARCHIV 2533 326, $7.98.

Tape: V* 3310 326, $7.98.

J. S. Bach: Chromatic Fantasia and Fugue, in D minor, S. 903.

C.P.E. BACH: Fantasias: in C minor, W. 254 (Pro bestiicke). in C, W. 61, No. 6; in C. W. 59, No. 6. W.F. BACH:

Fantasia in D minor, F. 19 (Capriccio).

MOZART: Fantasia in D minor, K. 397.

Unlike the plethora and variety of harpsichord recordings available today (four full double-columned pages are demanded by the 1976 SCHWANN ARTIST ISSUE listings), only a handful are devoted to the clavichord. Yet for some three centuries that was the most popular home and practice instrument, if only briefly-in the last half of the eighteenth century-a serious concert rival of either the harpsichord or the early square piano. So there should be a warm welcome for the present release by Tilney, especially for Archiv's admirably realistic recording of an exceptionally fine instrument: the five-octave unfretted clavichord built by Hieronymus Albrecht Hass of Hamburg in 1742 and restored in 1953 and 1975.

The sonic attractions here are perhaps particularly significant in that they give a more accurate notion of how a late-eighteenth-century clavichord actually sounded to its players and close-by listeners--with considerably more sonority than the small, even ethereal, tonal qualities with which it usually is credited in music-appreciation books. Although any clavichord is of course somewhat duller in tone than even quite small pianos, the bigger ones are not too dissimilar tonally from early-nineteenth-century square parlor pi anos, while still commanding distinctive differences.

That the instrument's peculiar potentials were best exploited musically by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach long has been generally accepted and is convincingly demonstrated in the present three, often unexpectedly eloquent, well-varied examples of his fantasias. The nimble Capriccio Fantasia by his elder brother, Wilhelm Friedemann, is scarcely less representative, but it is more suggestive (in its fugal sections) of Father Bach's keyboard writing while still unmistakably freer in idiom and more obvious in its showmanship.

At first thought, neither of the two other works properly belong in a clavichord program: Johann Sebastian's mighty Chroma tic Fantasia and Fugue was patently writ ten for double-manual harpsichord, and Mozart's K. 397 Fantasia of c. 1782 is specifically labeled "pour le pianoforte." But the former's inclusion is justified partly by the music's importance as an influential early fantasia exemplar, partly by its reminder that the composer and his pupils must have studied and practiced it on a clavichord as often as, if not more often than, on a harpsichord. The justification for including the Mozart piece is thinner, but Tilney's liner notes remind us that there was a clavichord in the Mozarts' Salzburg home and that "an eighteenth-century clavichord certainly comes closer to the sound of Mozart's piano than anything built in the nineteenth century." In any case, hearing this familiar mu sic in such unfamiliar guise does provide a fascinating new slant on it.

In general, Tilney's playing is a bit too de liberate and carefully articulated, but when he loosens up he is capable of both genuine feeling and bravura floridity. Yet it is the superbly authentic clavichord sound that makes this release an outstanding addition to the instrument's still too scant discography. R.D.D.

=============

The Tape Deck

by by R. D. DarrellClosing the Dolby circle. As the last of the majors, RCA, has finally made it unanimous by adopting the Dolby-B noise-reduction system, the musi-cassette plants a milestone in its astonishingly short, irresistibly triumphant history. In 1965, when Philips first brought us its barely two-year-old invention, who could believe that a 17/e-ips tape format ever could even remotely approach disc and 7 1/2-ips open-reel technologies? After all, it was only a few years earlier that cassettes' prototype model-RCA Victor's 1958 double-size, double-speed so called cartridge-had failed to catch on. At best, the tiny new format seemed destined to be limited to talk and pop materials for playback on battery-powered portables.

Well, as we all know, the tape size and speed handicaps were challenges that audio engineers rejoiced to meet.