by Arthur Jacobs

Documents only recently made available for examination disclose startling facets of the Victorian composer's life-style--and its influence on his music.

Is life a boon? If so, it must befall That Death, whenever he call Must call too soon.

THREE YEARS AFTER Arthur Sullivan's death in 1900, W. S. Gilbert was asked to choose the words to be inscribed on a bust of the composer. He selected four lines from The Yeomen of the Guard for the memorial, which stands by the River Thames in London, a few minutes' walk from the Savoy Theater.

But it is not to London that the Sullivan researcher must go. The majority of the vital documents, many of which have only in the past decade been released from private possession, rest in the Gilbert and Sullivan Collection of the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York. This store of thou sands of items includes letters to and from the composer, autograph scores, contracts, and ad dress books. The other main source of investigation is Sullivan's own diaries. Apart from a single volume at the Morgan Library, the diaries repose at the Beinecke Library at Yale University, having been acquired at auction in 1967. Exploration of all these materials points to a major re discovery of Sullivan.

-------- Arthur Jacobs is engaged in a full-length study of Sullivan un der a University of London grant. The Pierpont Morgan and Yale University Beinecke Libraries have kindly permitted quotation from documents in their possession for this article. --------

It is high time. Arthur Seymour Sullivan is probably still the best known of native English com posers; certainly his theatrical collaborations with William Schwenck Gilbert retain a vitality quite astonishing in view of the dusty oblivion that has overtaken other English musical and dramatic works of the late nineteenth century. Yet, precisely because the documentary material has only recently become accessible, the many books on Sullivan have been unable to accord him the critical and biographical scrutiny that is taken for granted with other composers of importance.

To a dearth of fact has been added a superfluity of legend. In both Percy M. Young's Sir Arthur Sullivan (1971) and Caryl Brahms's Gilbert and Sullivan (1975) may be found the story that Stravinsky and Diaghilev developed a passion for Gilbert and Sullivan in London in 1912, Diaghilev making Russian translations of the patter songs and shouting them out over his morning ablutions. This story, falsely ascribed to a tape-recorded interview with Stravinsky, was in fact an imaginative concoction of Stravinsky's publicity agent, Lillian Libman, with the approval of the composer's amanuensis, Robert Craft. The deception was confessed in Libman's book And Music at the Close, which was published in 1971 but evidently escaped the notice of Brahms.

Because of various contradictions of dates, the historical implausibility of the tale was spotted by Reginald Allen, curator and co-founder of the Morgan Library's collection. The modern documentary approach to Sullivan virtually starts with two of Allen's publications: Sir Arthur Sullivan: Composer and Personage, published by the Morgan Library as a catalog to its Sullivan centenary exhibition in 1975; and The First-Night Gilbert and Sullivan, a bibliographical, critical, and illustrated edition of the librettos, published in a limited issue in 1958 by Heritage Press, New York, and recently republished by Chappell of London in a revised edition.

Sullivan's story, if not exactly of rags to riches, at any rate exemplifies the social mobility open to artistic genius in Victorian England. Born the son of a military bandmaster in 1842, educated at the Royal Academy of Music (he won the first Mendelssohn scholarship there, enabling him to study further in Germany), Sullivan attained leadership on the London scene as both composer and conductor. Personal charm, as well as artistic gifts, won him acceptance in the highest social circles.

He had many friends both ma)e and female, but he never married. Though deeply attached to his mother (in later years, the anniversary of her death in 1882 was usually marked by a note in his diaries), he maintained a home separate from hers and pursued the active but clandestine sex life of a Victorian bachelor.

It is in the revelations of that sex life, to be traced in the diaries held by Yale, that the documentation is certain to be called sensational. But even this is not a wholly sensational interest. It contributes to the total portrait of the man. Sullivan's most active sexual period coincides with his busiest and most fruitful creative period, and the two activities decline together. In his last decade, failing in general health, he became an "old" man who was to die before he was sixty.

In a youthful courtship of Rachel Scott Russell, Sullivan's ardor had led him to an indiscretion that caused her family to bar him from the house.

That episode was long over when Sullivan-by now accepted as a leading musical figure in his country--began his long but always discreet affair with Mary Frances Ronalds, née Carter, of Boston.

That she was his mistress has long been strongly surmised and may now be regarded as certain.

-----

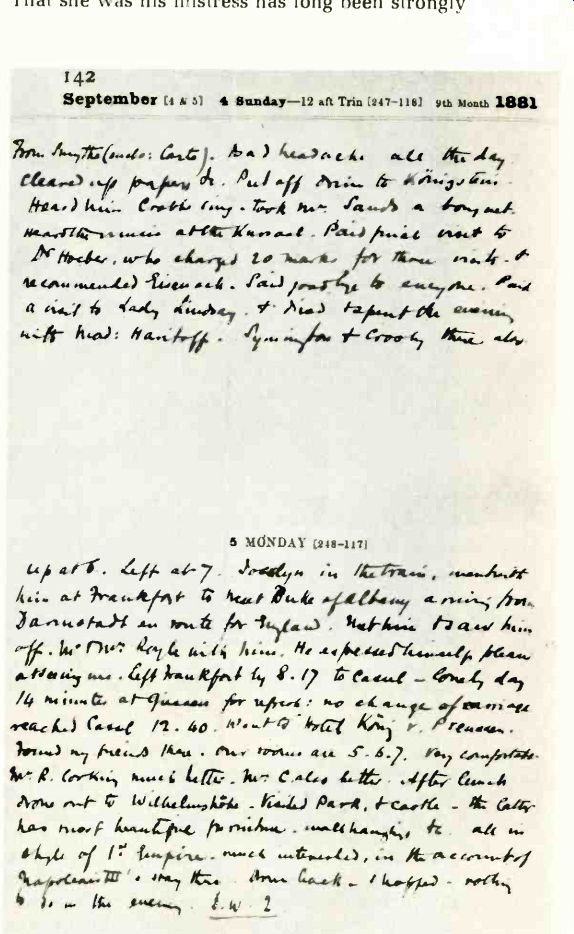

Above is a typical page from the Sullivan diaries, the bulk of which are in the Beinecke Library at Yale. It shows two entries (September 4 and 5, 1881) chronicling the ostensibly ordinary movements and encounters of a well-bred Victorian gentleman traveling abroad, in this case in the Rhineland and Hesse-Nassau: arrivals and departures, meetings and fare wells, visits to doctors and to the haunts of tourists. But the second entry closes with Sullivan's distinctive indication of a rather different kind of encounter: the underlined abbreviation "L.W. 2." For an interpretation, see the text.

------------

Wealthy and attractive, she lived apart from her American husband, Pierre, in an elegant part of London at 7 Cadogan Place. In 1877, when Gilbert and Sullivan were working on The Sorcerer as their first full-length operetta under Richard D'Oyly Carte's management, the name of Mrs. Ronalds is to be found on a select list of Sullivan's dinner guests, a list that also includes Princess Louise (Queen Victoria's twenty-nine-year-old daughter) and the Lord Chief Justice of England.

Mrs. Ronalds' intimacy with Sullivan was never broken. Renowned as an amateur singer, she received from the composer the manuscript of his most famous song, The Lost Chord, which was to be buried with her in 1916. Sullivan's visits to Cadogan Place are as prominent in the diaries as visits to the gaming clubs where he sometimes lost hundreds of pounds in a night.

It has been inferred-particularly by Leslie Baily in The Gilbert and Sullivan Book (1952)-that Mrs. Ronalds was the "LW." found in amorous references in the diaries and that those initials stood for "little woman." But it can now be stated that this is not so. Mrs. Ronalds is named openly hundreds of times; L.W. is someone else, and the two are occasionally mentioned in the same day's entry. L.W. is at times abbreviated further to "L.," so these are presumably genuine initials. And there is a third mistress, "D.H." Unlike Mrs. Ronalds, seen constantly in Sullivan's company (though always in circumstances of propriety), the other two apparently met him only in private. Their social positions can only be guessed at.

----------

Sir Arthur (top row, right) and Mrs. Ronalds (in front of him, holding a cup) were photographed in 1891 with other guests at a house party at Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire, the family seat of the Churchills and the birthplace of Winston seventeen years earlier.

--------------

--- A cartoon of Sullivan (1887) by Charles Dana Gibson, creator of "the

Gibson Girl" ------

Sullivan's sexual encounters-both in London and on his many trips to the Continent with one or more prearranged companions-are recorded in the diaries, sometimes with a tick or a figure apparently denoting the number of orgasms he achieved. At Kassel on September 5, 1881: "Found my friends there. Our rooms are 5, 6, 7.... Nothing to do in the evening. L.W. 2." And the next day: "L.W. (1) straight up! . . . Himmelische Nacht (1)." (The German expression for "heavenly night" Sullivan invariably misspells "himmlische" as "himmelische"-recurs, sometimes abbreviated.) In the same year (the year of Patience) we find more such entries: September 9, "Himmelische Nacht (2)"; September 10, "Him. N. (2)." In April 1882, when he meets D.H. in Paris, the numbering is also found (but not the German expression). Back at home the forty-year-old Sullivan jots down a wry entry for August 25, 1882: "D.H. (1). L.W. (0! disappointed ambition!)" The "0" would seem to be a zero, not an equivalent of "oh." Amid the taboos of Victorian society, such a life inevitably had its penalties and its fearsome anxieties. On December 11, 1884, "Uncertainty changed to conviction"; December 12, "Went to M. alone"; December 13, "Things very bad. Took D.H. to M. Usual course advised." Evidently M. was either a doctor who performed abortions or an unlicensed abortionist. On both December 19 and 20 the diary reported with relief, "Signals of safety." This was not, incidentally, the only such occasion noted.

But by the 1890s--and it should be remembered that Sullivan was only fifty in 1892-a remarkable change is seen in the diaries. They not only are much more sparsely filled, but contain hardly any indications of sexual activity. Moreover, Mrs. Ronalds has become "Auntie"! This appellation must have been adopted first for the benefit of Herbert Sullivan, the composer's young nephew, who lived with him. But now it was used without irony by Sullivan himself. A remarkable indication of change of role, it would seem--all passion spent.

Here the correlation between Sullivan the man and Sullivan the composer suggests itself.

A brief survey may serve to recall the concentration and curve of his professional activities-of which his collaboration with Gilbert, although exceptionally lucrative, was only a part. The period of their successful association runs from Trial by Jury (1875) to The Gondoliers (1889). The two works that failed are Utopia Limited and The Grand Duke, both of the 1890s. It was also in the 1880s that Sullivan won his greatest success out side the operetta field with The Golden Legend.

Enormously popular in its day, it is a quasi-religious cantata on a text by Longfellow and spans half an evening in performance. At this time too he was occupied with the greatest--yet most stimulating--burden of other activities: principal of the newly founded National Training School for Mu sic (now the Royal College of Music) from 1876 to 1881 and conductor of the Philharmonic Society of London from 1885 to 1887. Outside London he was in constant demand as a visiting conductor.

The energy of his trip to the U.S. in 1879-80 is evident from his own accounts, as well as from newspaper interviews. He and Gilbert came to the States to tour with H.M.S. Pinafore, and then, to forestall American promoters who had cheated on copyright with that operetta, launched a production of The Pirates of Penzance. But Sullivan stayed, on and journeyed as far as Salt Lake City and Los Angeles. He little knew that one of his posthumous American "legacies" was to be the song "Hail! Hail! The Gang's All Here," based (in circumstances that are still uncertain) on "Come, friends, who plough the sea" from Pirates.

Another commitment from 1880 onward was Sullivan's once-yearly trip, with a great deal of preparatory work, to England's northern city of Leeds, as conductor of its choral and orchestral festival. This was one of the few major posts that he retained until late in life (1898). But otherwise it may be seen that by 1890 he was in a general and not merely an artistic decline. Physical ailment basically, it would seem, a kidney problem resulting in painful discharges--had taken its toll for several years. Following the custom of those Victorians of both sexes able to afford it, Sullivan repeatedly went to "take the waters" at German and French spas, and his diary records his impatience when obliged by doctors there to desist not only from exercise, but even from what he called "head work." Reticence on medical matters and a complete exclusion of sexual considerations are features of the authorized biography of Sullivan by his nephew Herbert, in collaboration with Newman Flower (1927, revised 1950). Such a hagiographical approach was, at that time, perhaps understandable. What is astonishing in that book is the inaccuracy of its transcriptions from the letters and diaries-even in quoting from the texts of op eras. It refers to "O buy, buy" instead of "O bury, bury" and "Cachnalia" for "Cachucha" in The Gondoliers, and it quotes Gilbert as referring to The Tower Warden as a possible title for The Yeomen of the Guard and to "tower wardens" in general. (The official name for these guards of the Tower of London is not "warden," but "warder," and Gilbert never wrote anything else. The word survives, of course, in the text of the operetta, al though it is eliminated from the title.) It need hardly be said that the extracts found in the Sullivan-Flower biography have been faithfully copied by subsequent commentators.

The newly accessible information obliges us not merely to add to, but also to correct, the meager excerpts already printed from the letters and diaries. We may now, like prospectors gazing at an obviously rich yet barely exploited mine, consider some of the ways in which these American holdings will bring enlightenment. First of all, they re veal a good deal about the day-to-day working of the two collaborators, the changes in both words and music as the work progressed, the scheduling and management of rehearsals. We learn of Sullivan's method of composing a song and then of "framing" it in place, and why (to avoid doing work that would eventually be thrown out) he deferred orchestration until rehearsals were well advanced and alterations and substitutions necessarily made. But in fact alterations continued until almost the last moment, as the diary records only three days before the opening of The Yeomen of the Guard in 1889. December 4: "Settled to substitute second quintet ['Here is a fix'], previously cut, for first one ['Till time shall choose'] much to everyone's delight." Indeed, changes continued even after the first night. December 8: "Gilbert sent me alteration and substitute for No. 4 [first act]." Researchers whose field is the social history of music will learn, to their surprise, that male altos (as well as contraltos) continued to be used in the amateur chorus of the Leeds Festival. They will find Sullivan occupied with the making of special trumpets for a performance of Bach's Mass in B minor and of special bells for The Golden Legend.

They will learn what many musicians were paid.

And they will read of the struggle of British per formers and companies against snobbish preferences for the foreign artist. In a letter dated May 19, 1884, he wrote: "I think all this musical education for the English is vain and idle, as they are not allowed the opportunity of earning their living in their own country." They will note Sullivan's interest-one of his few instances of a broadly ethical stand-in encouraging Sunday concerts for the poorer classes, presumably against the stern de fenders of the Victorian Sunday as a day without secular pleasures.

The autograph full scores at the Pierpont Morgan Library-notably a Trial by Jury that displays many discrepancies from the printed vocal scores used today-should stimulate a new critical study of the music itself. Although Sullivan's works are out of copyright, few are available in authentic form. Some autograph scores are accessible at the British Library reference department (formerly a section of the British Museum) and elsewhere; but the only " Savoy operas" that have ever been printed in full score are the pirated German scores of H.M.S. Pinafore (c. 1883) and The Mikado (1893), both long out of print. (The Gregg Press facsimile of The Mikado in Sullivan's autograph does not constitute an edition in the normal sense.) The scores in the Morgan Library collection are not, however, confined to the stage works, with or without Gilbert. Autographs and rare early printings of other works are also on hand.

But for the layman, the material at both the Morgan and Yale libraries is of greatest interest for what it tells us about the "private" Sullivan. Had he been a contemporary poet or painter of equal stature this would surely have been uncovered long ago: One thinks of the biographical attention already paid to Wilde, Ruskin, and Rossetti and, incidentally, of the sexual revelations in each case.

Similarly, when we discover the identities of L.W. and D.H., we will have learned something valuable about a remarkable composer--if not one of the world's major composers, then one who has a special place in the uniting of sophisticated and popular taste.

(High Fidelity, May. 1977)

Also see:

Link | --Link | --Do We Overestimate Beethoven?

Link | --Classical Records (May 1977)