Reviewed by: John Canarina Scott Cantrell Kenneth Cooper R. D. Darrell Kenneth Furie Harris Goldsmith David Hamilton Dale S. Harris R. Derrick Henry Nicholas Kenyon Allan Kozinn Paul Henry Lang Irving Lowens Robert C. Marsh Karen Monson Robert P. Morgan Conrad L. Osborne Andrew Porter Patrick J. Smith Paul A. Snook Susan Thiemann Sommer

BEETHOVEN: Sonata for Piano, No. 28, in A, Op. 101. RAVEL: Gaspard de la nuit. SCHUMANN: Toccata in C, Op. 7. Jorge Luis Prats, piano. (Heinz Wildhagen and Hanno Rinke, prod.( DG Concours 2535 010, $6.98.

LISZT: Sonata for Piano, in B minor.

CHOPIN: Polonaise in A flat, Op. 61 (Polonaise-Fantaisie); Etude in A flat, Op. 10, No. 10.

Diana Kacso, piano. [Heinz Wildhagen and Hanno Rinke, prod.( DG CoNCOURS 2535 008, $6.98.

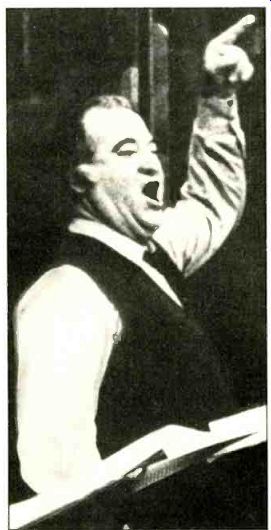

------------ Giuseppe Taddei recording the title role in Karajan's new

Falstaff.

Here are the two additional Concours piano discs mentioned in my January review; DG has decided to issue them in America after all.

I identified twenty-five-year-old Jorge Luis Prats as a French-trained Cuban, information gleaned from the press release; as it turns out, he graduated from Havana's College of Art and then went to Paris to win the Concours International Marguerite Long-Jacques Thibaud. His pianism is obviously on a very high level: Finger dexterity is formidable, and chords are voiced with an impressive gleam and solidity. Particularly noteworthy are his vibrant, expansive account of the Schumann toccata and his tautly propulsive Gaspard. The Schumann is paced rather broadly; the molding of phrases, placement of crucial accents, and intertwining of quasi-symphonic inner-voice strands give off an aura of tremendous authority. A few of the harmonies sound slightly "enriched," but that may simply be the result of the performance's unusual clarity and precision. The exposition repeat is observed. The Ravel might not have quite the frightening mystery of certain readings (Argerich's, for instance), but Prats is able to execute the treacherous figurations at a hair-raising clip with minimal dependence on the sustaining pedal.

The tight, sprinting compression of "Scarho" almost defies belief.

Prats's approach to Beethoven's Sonata, Op. 101, is very reminiscent of Horowitz' late-Sixties concert account and of an old Epic recording of the Hammerklavier (Op. 106) by Eduardo del Pueyo: Solid in tone, crystal-clear in articulation, and a bit garish in its glaring definition of inner lines that might have been better left to their own resources, the music sounds like a distant cousin of Albéniz' Iberia. Curiously, Prats fills in the octave A of last-movement measures 3 and 201. The reproduction seems more luminous than that of the other Concours debuts (although both of these discs, like the earlier releases, were taped in recital in Munich). If the Prats recital impresses, the work of Brazilian-horn, Juilliard-trained Diana Kacso disappoints. I her playing is woefully heavy-handed, with little heed paid to balancing the globs of sound she elicits from the instrument and with a mindlessly self-indulgent distortion of rhythm and phrase that serves no structural or aesthetic purpose. The Liszt sonata goes on forever in this studentish performance, far from note-perfect and not very intense; the Chopin Polonaise--Fartaisie is slightly better--if only because the music itself goes so much deeper-but the A flat Etude is coarse, percussive, and over-pedaled. That a banger like this can place so high in more than one competition (Kacso took first prize in the Carreño in Venezuela and the International Chilean contest and Gold Medal at the Arthur Rubinstein in Israel) is a depressing commentary on the usefulness of such marathons. To make things worse, the Liszt sonata is broken between sides-as inartistic as it is unnecessary. H.G. BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 3, in E flat, Op. 55 (Eroica). A Berlin State Orchestra, Otmar Suitner, cond. jI heinz Wegner and Toru Yuki, prod.' DENON OX 7202-ND, $15 (digital recording; distributed by Discwasher).

COMPARISON: Scherchen /Vienna St. Op. Orch.

Westminster WG 8352 I here, as predicted, is an alternative to Mehta's digital Eroica (CBS IM 35883, January). Otmar Suitner, a respected East German conductor, will he recording all nine of the Beethoven symphonies for Denon.

In its way, the performance is worthy of respect: This is a chamber-orchestra presentation, mindful of Beethoven's original orchestration-even to utilizing the archaic valveless trumpet parts at the end of the first movement (also used by Scherchen in his small-scaled yet utterly different recording). The Berlin Staatskapelle plays with unanimity and poise-worlds removed from the sense of challenge and restless stridency of the Scherchen-driven Vienna State Opera Orchestra-and in an abstract way, one can admire the sleek, cool dispatch, the classical equilibrium. Tempos tend to be brisk, yet Suitner, unlike Scherchen, complacently places the great work in an eighteenth-century context (though not in a way that points up its revolutionary aspects); here the lightness of texture and mercurial sense of movement produce a chilly decorum. In truth, this approach does not particularly appeal to me, and I suspect that its formality and low-keyed primness will limit the record's circulation.

Suitner observes the exposition repeat in the first movement, in line with the current trend, and Denon's layout allots an entire side to that movement's 18:40, with the final three movements ( 15:00, 5:26, and 11:04) consigned to Side 2. The sound, a bit cool and analytical, is predictably smooth and undistorted. H.G. BOND: Peter Quince at the Clavier`; Monologue GILBERT: Transmutations'; Interrupted Suite". Penny Orloff, soprano and percussion; Zita Carno, piano. Ronald Leonard, cello.** Thomas Harmon, organ; Scott Shepherd, percussion.' Gary Gray, clarinet; Delores Stevens and Richard Grayson, pianos; Susan Savage, prepared piano." [Jane Courtland Welton, prod.] PROTONE PR 150, $7.98 (Protone Records, 970 Bel Air Rd., Los Angeles, Calif. 90024). Victoria Bond and Pia Gilbert both have senses of humor, bless them, and they also have in common remarkable abilities to communicate musical gestures and thrust. Both have written for dance, of course, but even in the extra-terpsichoric works that Gilbert calls "music per se," there's a feeling of athleticism and implicit choreography.

The best piece here is Gilbert's Interrupted Suite for clarinet and three pianos, one of these prepared with dowels or manicure orange sticks and rubber erasers. Paying homage to Stravinsky, the suite has nine short sections (including a march, waltz, and tango), interrupted by unexpected and genuinely funny little asides that turn 180 degrees from the established style.

There's less humor in Gilbert's Transmutations for organ and percussion, conceived both to stand on its own and to serve as a dance score. The fun is to try to figure out when the organ leaves off and the percussion takes over. (A couple of octaves of pipes were removed from the organ in UCLA's Royce Hall for performance and recording, to give the windy effects.) Transmutations is filled with fascinating sounds and imaginative give-and-take, but it lacks direction, despite a fine performance by organist Thomas Harmon and percussionist Scott Shepherd.

Bond has bravely tackled a problem that has defeated most composers over the years: She has set a poem that deals with music, specifically, Wallace Stevens' Peter Quince at the Clavier. Soprano Penny Orloff (who also hits the tambourine) and pianist Zita Carno deliver the song with great spirit. But Bond's idea of Quince's music is radically different from mine despite her colorful evocation of Byzantium, and I suspect that this poem is best left to sing in the individual reader's imagination; this is, after all, where Stevens wrote, "Music is feeling, then, not sound." Filling up Bond's side of the disc is Monologue for solo cello (Ronald Leonard), excerpted from a piano trio that was written as a ballet score. The Bach-like Monologue is appealing; it makes one wonder what the rest of the trio is like. K.M.

CHOPIN: Polonaise in A flat, Op. 61 (Polonaise-Fantaisie); Etude in A flat, Op.

10, No. 10-See Beethoven: Sonata for Piano, No. 28, Op. 101.

DEBUSSY: Preludes, Book I. Claudio Arrau, piano.

PHILIPS 9500 676, $9.98. Tape: 7300 771, $9.98 (cassette). The slightly square-cut phrasing and liquid sound of Danseuses de Delphes sets the mood for this admirable performance. Arrau combines Grecian detachment and a mastery of color with a vein of mellow poetry. The clear articulation and solidly granitic sound produce too tangible an impact in Voiles, and Ce qu'a vu le Vent d'ouest and the central episode of La Sérénade interrompue don't quite come off. Yet other items are sublimely re-created: The slow tread and rapt intensity of Des Pas sur le neige poignantly convey the benumbed sorrow of Debussy's direction--"Like a sad and tender regret"; Minstrels and La Danse de Puck have a touch of wry deliberation and perfect clarity of "diction"; and La Cathédrale engloutie emerges with bronzed grandeur. The straight landscapes and portraits such as Les Collines d'Anarapri and La Filie our cheveux de lin may suggest Rembrandt or Van Gogh more than the usual Renoir, but they are none the worse for the touch of robust expressionism.

This release is particularly welcome as evidence of Arrau's continued pianistic well-being after his worrisome account of the Chopin waltzes (Philips 9500 739). Philips' radiant, robust piano tone admirably frames the performance. Highly recommended.

H.G. GILBERT: Transmutations; Interrupted Suite-See Bond: Peter the Clavier; Monologue.

GOUNOD: CAST: Mireille Vncenette Clémence/Voice from Heaven Taven Mireille.

Quince at Mirella Freni (s)

Christiane Barbaux (s)

Michele Command (s)

Jane Rhodes (ms)

Shepherd Luc Terrieux (boys)

Vincent Alain Vanzo (t)

Ourrias Iosé van Dam (b)

Ramon Gabriel Raclin ier (bs-h)

Ambroise Marc Vento (bs-h)

Ferryman lean-Jacques Cuhaynes (bs)

Chorus and Orchestra of the Theater du Capitole ( Toulouse), Michel Masson, cond. 'Eric Macleod, prod., ANGEL SZCX 3005, $30.94 (three discs, automatic sequence). There is a sense in which the literary and cultural background of Mireille is more fascinating than the opera itself. Yet the piece has a great deal that is charming and even moving, particularly if one makes an effort at understanding the impetus for its composition and allowing some of the resonance of that background to sound.

One of the strongest undercurrents in French literature of the mid to late nineteenth century was that of the Provençal revival. At its leading edge were the poet Frédéric Mistral and his companions of the so-called Félibrige, the society that strove to restore to literary dignity the Provencal tongue. Of even wider influence was Alphonse Daudet, who wrote in French, and whose extremely popular novels, plays, and stories were built on the rigid pride and independence of Provencal character, the ruinous familial warfare of the region's resistant patriarchal tradition, the clash of that tradition with the urban Northern modes, or the braggadocio of the legends of old Provence.

And that legendary tradition is of incomparable richness. Provence, the home of troubadours, the seat of courtly love, and before the obliterative Albigensian Crusade one of Europe's important political, cultural, and religious powers, was for centuries the most volatile meeting ground of Eastern and Western, pagan and Catholic, ways of being-a mingling still marked today by (among other manifestations) the pilgrimages at the Chapel of Saintes-Mariede-la-Mer (the setting of the last act of Mireille), where Catholic and Gypsy rituals intertwine.

Musically, the specifically modern Provencal fallout has been rather specialized, but often delicious: Bizet's magnificent incidental score for Daudet's L'Arlésienne and Cilea's opera on the same subject, Massenet's passionate setting of the same author's novel Sapho, and just a bit to one side Canteloubé s collections of Auvergne songs. Also of some operatic interest: the basic conflict of La Traviafa, and Tchaikovsky's Manta, which is set at the court of René the Good of Irovence, in whose reign the pilgrimages of the Three Marys were established.

And Mireille, set to a libretto by Carré from the poem by Mistral, called Mir?io. Mistral's work was based on a true incident (as was, incidentally, Calendal, the Mistral epic from which Daudet derived L'Arlésienne-Mistral was a poet and romancer, but a realist chronicler, too). The libretto concerns the beautiful Arlésienne Mireille, who loves Vincent but conies up against two obstacles: rival suitors, and the aforementioned patriarchal tradition. Vincent is only the son of a basket weaver, while the principal rival, Ourrias, is a proud gardien, or hull-tamer--an honored calling in the society. Mireille's father, Ramon, will have nothing to do with a marriage between Mireille and Vincent; further, the enraged Ourrias waylays Vincent and strikes him an apparently fatal blow.

However, Ourrias has elected to fight on ground belonging to the pagan occult forces-dark spirits drag his boat beneath the waves of the Rhone, and the Gypsy woman Taven nurses Vincent hack to health. Hearing of this, Mireille resolves to keep her oath to meet Vincent in time of misfortune at the Chapel of the Three Marys. But to reach Saintes-Marie, she must cross the blazing wasteland called The Crau. Inspired by the old legend of Magelone and by a vision of the Three Marys, she reaches the chapel and is briefly reunited with Vincent, but dies as heavenly and earthly voices sing of her transfiguration.

Well. You have to be there. Listeners will be disappointed in Mireille if they approach it in hopes of a profound grand opera. It is a gentle, lyrical work, almost operetta-ish for much of its course, soaked in the country flavor of its source. It has as much in common with many Eastern European folk operas as with the five-act French grand opera form it nominally represents.

The opera's history has been a troubled one. Gounod had trouble with Marie Miolan-Carvalho over the title role, trouble with the Theater Lyrique management over scenes rated I'G for its audience, trouble finally with the audience. He rewrote the work, cutting and rearranging and substituting a light-opera, everything-works-out after-all ending. In this form, the piece became quite a success, and it was not until the 1930 that the conductor Henri Büsser reconstructed the composer's original version-indeed, the only score I've been able to track is of the rewrite, dated 1901 and labeled "Nouvelle edition de L'Opéra-Cornique." This recording, like Angel's previous one (Aix-en-Provence, 1954, under Cluytens) is of the Büsser reconstruction. It is strong enough to recommend to anyone interested in exploring the work, which is a very rewarding one provided one accepts its parameters and can live with the fact that its heights are similar to, but not quite as exalted as, the comparable passages of Faust or Romeo et Juliette. (I don't make this comment snidely: I'm among the dwindling few who think Gounod is Actually Good.) And it is not all bucolic sprackle. Though the supernatural scenes have only the mildest demonic seasoning, like lobotomized Berlioz, they are still fun. The familial confrontations make a fine concerted finale for Act II, and Mireillé s big solo Scene de la Crau (a much-rewritten passage) has some splendid opportunities. The opera's best-known arias (the tenor's "Anges du Paradis,", the soprano's "Mon Coeur ne pent changer") are solid ones, as are Ourrias' less-known couplets.

The showy waltz-song, "O légere hirondelle," included as a separate band on the earlier recording and oft-recorded separately, is omitted from this set.

Given (as we are) the absence from the world of any outstanding French soprano, Mirella Freni is a logical enough choice for the title part. Since the role is more lyrical than some she has been taking on recently, it encourages many of the better aspects of her vocalism, and in the early going her singing is cleaner and more equalized than has often been the case, with some very nice high decrescendos tossed in. Later, things bog down a hit for her-she doesn't really feel how to guide the line in a passage like the allegro B section, "A toi mon ame," of her principal aria, and there is a faintly blowsy, slow-to-speak quality to the voice that doesn't serve the music well. Still, it's a warm, sizable lyric soprano, if no longer of the freshest, and she has her moments.

Her tenor, Alain Vanzo, has a clean, strong lyric tenor with an appealingly tender timbre. He tends to hook into notes from underneath and to lift "off the voice" to sing piano, hut this is a good, well-used voice of the correct sort for the part. Poetic or dramatic he isn't, of rubato and portamento he hasn't heard-dig out Georges Thill's recording of "Auges du Paradis" if you are so sticky as to insist on music.

José van Darn is a most imposing Ourrias. His voice sounds beautiful and strong, the role lies exactly in its best tessitura, and his straightforward style is well suited to the assignment. Gabriel Bacquier turns in decent work in the bass role of Ramon, rather firmer than I'd expected. But I particularly miss the older recording here, for the excellent true bass voice and dignified style of André Vessiéres. Jane Rhodes appears to be a good artist who can be compelling in the theater, but on records her Taven isn't very enjoyable-some nice touches are compromised by sour, strangely pitched tone of little or no vibrato. As on a couple of recent recordings, the light soprano Christiane Barbaux turns in pleasing singing in a secondary role.

Michel Plasson has the score well in hand. At times his reading has more vitality and thrust than Cluytens's, but at others he doesn't capture quite the skip or lilt of lighter spots-there is no lift to the little sixteenth rests in the accompanying figure of the Magnarelles chorus, for example. His orchestra is a capable one that in fact sounds well above average much of the time, and whose tone is complete with the French brass timbre. The engineering, heard in close juxtaposition with that of the old mono performance, is a blessing for its detail and full encompassment of the orchestra, a curse every time the voices of Freni and Vanzo rise into their upper ranges and into a resounding void of studio reverb. The accompanying booklet, with translation, some notes, and a few photos, is an adequate one, but find if you can a copy of the old one, which is among the most helpful, complete, and handsome ever done for a record album.

It's good to have Mireille back. I suggest a little soaking-in time, but I think the work will beguile you, given a chance.

HAYDN: Symphonies (12)-See Mozart: Symphonies, Vol. 4.

LISZT: Sonata for Piano, in B minor-See Beethoven: Sonata for Piano, No. 28, Op. 101.

THE MANNHEIM SCHOOL. For a review, click here.

MOZART: Symphonies, Vol.4: Salzburg, 1773-75. Academy of Ancient Music, Jaap Schróder, violin and dir.; Christopher Hogwood, harpsichord and dir. [Morten Winding, prod.] L’OISEAU-LYRE D 170D3, $29.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape: K 170K33, $29.94 (three cassettes).

Symphonies: in D, K. 121; in D, K. 203; in D, K. 204; No. 25, in G minor, K. 183; No. 28, in C, K. 200; No. 29, in A, K. 201; No. 30, in D, K. 202.

MOZART: Symphonies: No. 25, in G minor, K. 183; No. 29, in A, K. 201.

HAYDN: Symphonies: No. 92, in G ( Oxford); No. 103, in E flat (Drum Roll).

R--Berlin Radio Symphony Orchestra, Lorin Maazel, cond.

QUINTESSENCE 2PMC 2709, $11.96 (two discs) [from PMC 7149* / 57', 19801.

MOZART: Symphonies: Nos. 40, in G minor, K. 550; No. 41, in C, K. 551 (Jupiter). London Symphony Orchestra, Claudio Abbado, cond. [Rainer Brock, prod. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2531 273, $9.98. Tape: 3301 273, $9.98 (cassette).

HAYDN: Salomon Symphonies, Vol. 1.

R--Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Thomas Beecham, cond. [Lowrance Collingwood and 'Victor Olof, prod.' ARABESQUE 8024-3, $20.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape 9024-3, $20.94 (three cassettes)]. From EMI-CAPITOL GCR 7127, 1958.1

Symphony No. 40, in F. Solomon Symphonies*: No. 93, in D; No. 94, in G (Surprise); No. 95, in C minor; No. 96, in D (Miracle); No. 97, in C; No. 98, in B flat.

HAYDN: Symphonies: No. 86, in D; No. 98, in B flat*; No. 101, in D (Clock); No. 102, in B flat.

Concertgebouw Orchestra, Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 9500 678'/9', $9.98 each. Tape: 7300 773'/4', $9.98 each (cassettes).

"Modified rapture" was the term I borrowed to describe my reaction to the first release of the Academy of Ancient Music's Mozart symphony cycle, recorded on original instruments (Vol. 3, D 169D3, May 1980). To the second issue (Vol. 4 in the series, covering the Salzburg symphonies of 1773-75) the reaction must be much the same. I wish that my rapture could have been a little less modified this time around, that noticeable improvements in the playing showed that lessons had been learned from the first set. But such are the pressures of the recording business that this volume must have been taped before the first recordings even hit plastic. So the gins of an original-instrument account--and they are many-remain substantially unchanged; the drawbacks, alas, are as much in evidence as before.

The music in this set presents a greater challenge. In the first box, there were brilliant, enchanting, but little-known works. This volume takes the leap into what historians have, rightly or wrongly, described as Mozart's symphonic maturity; it opens with the "little" G minor, K. 183, and the A major, K. 201. The Academy shows the same skills it did in the earlier music; it takes no account of the works' greater subtlety. This approach is in line with Neal Zaslaw's demythologizing of the whole concept of the "weighty" symphony in his booklet notes. But I think that here listeners will begin to miss something in the performances, and while they may often he misguided in doing so, their instincts may sometimes he right.

The G minor, for example, emerges very cool and restrained. Some of its colors are freshly revealed: in the first movement, a striving, yearning oboe solo, and lovely reedy low trills in the violins in the final bars. Both here and in the finale, though, steady control replaces genuine rhythmic tension; the finale comes out jaunty without enough sense of surprise. The Andante flows well, but in short phrase-lengths; the Minuet, with its rustic wind trio, is a great success.

The opening of the A major provides an object lesson in the benefits of the old instruments: The winding, rising and falling octaves of the second violins can penetrate the texture clearly. Throughout the symphony the horns make a crisp impact usually absent from modern accounts, where they merely fill in. In the bustling last movement, though, the sound of the first violins' grace notes (in the gentle second subject) is unacceptably acid and ill focused: a pity, because this finale goes with real zip, especially the sudden string scales that shoot into silence and the rasping horn calls. A loose note, perhaps from a bassoon, on an upbeat in the coda really should have been retaken. There is a need for sharper characterization in the middle movements and clearer articulation of the dotted rhythms in the Andante, which tends to drift; throughout, the clarity of the bass lines is slightly clouded by the ample acoustics. One tiny textual point: In his new book, Erich Leinsdorf makes a fuss about a bass note in the score of the first movement that is placed on a different beat in exposition and recapitulation. He insists that it should be altered for the sake of consistency, but Zaslaw, who knows his sources as well as anyone, has not done so here, and the effect is not in the least disconcerting.

The other items in the box include two "real" symphonies, K. 200, in C, and K. 202, in D; two symphonies extracted from longer serenades; and the Symphony, K. 121, that Mozart made by adding a finale to the overture for La finta Giardiniera. The C major is a ravishing work, eloquent and singing, with a superbly simple slow movement theme that takes wing in this performance, allowing inner parts to he heard and creating the maximum surprise out of the long wind note that shifts the music into the minor. A touch more of refinement and grace is needed, but the Academy here has precisely the right sort of eloquence-not rich and puffy, but quiet and noble. The Presto finale goes well, too, with a hard-edged clarity that accumulates considerable power. In contrast, the D major receives a curiously lackluster performance, with weak trills (an all-important feature of the first movement) and only a staid, neat account of the wonderfully witty finale with its pauses and unexpected harmonic shifts.

The serenade symphonies, both also in D major, fare much better (as did the D major symphonies in the first volume), possibly because the music is generally less substantial. There is a very impressive feel to the first movement of K. 204, with its thin, hard drums. The Andante of K. 203, with its Cosi-like murmuring in the second violins, is sensual and colorful; here the lack of density in the sound makes the feeling of exoticism much greater. There is some sloppy wind playing in the opera overture; elsewhere ensemble is generally good.

It is difficult to account for the variability of standard in these performances, except to say that some movements are clearly easier to play than others. But some serious improvements--long-scale planning in the fast movements, shapely phrasing in the slow ones, absolute precision of tuning and chording, and finally, a sense of enjoyable abandon in the music-making need to be felt before the Academy tackles the later symphonies.

To turn to some of the other recordings here, however, makes one realize how much we owe to the Academy and other similar groups for refreshing our ideas of how classical symphonies can sound. Lorin Maazel, on what I presume are old recordings (though no date is provided), gives performances of the G minor and A major symphonies that may, at one time, have seemed surprising. They are firm, detached, at times rigid, and though the Berlin Radio Symphony's playing is never less than tolerable, the interpretations are quite devoid of understanding. Maazel has an alarming way of slowing down for a slow theme, even in a sonata-form movement, and the overall blandness of sound emphasizes how much we hear in original-instrument versions that has been amiably smothered all these years. A generalized fervor pervades his "little" G minor, and a doting sentimentality characterizes his A major. (The Haydn performances present the notes clearly, but are still more depressing because they lack any response to the wit and sparkle of the music.) He shows us many aspects of conventional Mozart performance that I would not he sorry to lose.

So, I regret to say, does Claudio Abbado. The playing here is in a quite different class: The London Symphony can do everything its new principal conductor wants, and the sound engineers give the result an opulence and shimmering beauty that would he hard to surpass. The start of the great G minor Symphony, No. 40, emerges out of a heat-haze accompaniment into a melody that pulses its way as if fluttering in a sudden breeze. When the tutti enters, the massed cellos and basses chug smoothly like a gas-guzzler with cushioning suspension clinging to the road. The emphasis of the performance is on sound; musical content finishes a poor second. I have rarely heard an account of this symphony's Minuet that derives so little tension from its marvelous counterpoint, or one of its finale that makes the earth-shattering start of the development section sound so natural and comfortable.

The Jupiter receives a better performance; Abbado is here not so concerned with warmth of expression, and the trumpets ring out with firmness and strength. But there is always a pudgy edge to the chords, a gluey spreading effect, which alerts us to the fact that in such readings ensemble is always and necessarily approximate. The rhapsodic slow movement has a Malllerian imaginativeness to it, but might it not be even more powerful if all those dissonances really hit the heat together? The finale's contrapuntal splendors shine, but there is a sequence-just after the recapitulation has started-full of tritones and chromaticisms (bars 233-53) where we should surely feel that the music is about to collapse. Giulini, on an old Philharmonia recording, did it with immense, suppressed power; Abbado, like Muti in the concert hall, pushes on gaily through it, as if it were straight recapitulation.

For performances that really make one aware of what an old-instrument approach will always lack, one must turn to Haydn, and to Beecham. Beecham's remarks about Haydn's having, in old age, a face "like ripe old port," helps us to understand his marvelous interpretations of the Salomon Symphonies. He somehow manages to turn Haydn into a witty old English gentleman, sitting in his leather armchair in a London club over a glass of something strong, delighting us with a stream of melodic, modulatory anecdote that has no reason for existing other than pleasure in its own sense of self-amusement. His performances are chubby, smiling, warmhearted, and concerned with effect rather than with meticulous detail.

These reissues are from the 1958 set he recorded with the Royal Philharmonic (though again, and more irritatingly, no recording dates .ore given). They have an ample sound and are gentle and relaxed in their impact. The finales are wonderful--the sparkle and surprise of these movements seems to bring the best from Beecham. In the first movements he is little concerned with the symphonic argument, but the material itself is presented with a delicious range of inflection and careful shaping. The minuets are stodgy, and the slow movements sometimes moving, sometimes self-indulgent. At some important points, tension is lacking-especially in fugal or imitative episodes, like the one that electrifies the finale of No. 93. The vital quality that is missing here is tautness: tautness of musical argument, tautness of phrasing. These performances should be treasured; no one should think, however, that they can he re-created today. Beecham's Haydn is a glorious period piece.

Colin Davis represents a fine, modern alternative to the Beecham approach.

In the only direct comparison, in No. 98, he is sometimes faster, sometimes slower, but always more careful, always concerned with detail. He shows, too, how a modern symphony orchestra with a lush sound can create highly intelligent musical results.

The Concertgebouw has an ample breadth to its textures, and the recording is not dry; yet a comparison between this and the Abbado/London Symphony record shows that the precision Davis achieves is always greater. Slightly scaled down, the sound would be ideal for llaydn; as it is, one regrets only a certain inflexibility. Davis is almost as skillful as Beecham at letting the rhythms dance, but he falls marginally short in letting the quirkiness and sheer delight of these symphonies communicate themselves.

It will he exciting to hear Haydn's symphonies, with their varied and imaginative scorings, on original instruments; one cycle is in preparation, and I hope it will be well prepared and recorded in installments, so that players and listeners alike will have the chance to enter gradually into a new sound world. N.K.

RAVEL: Gaspard de la nu it-See Beethoven: Sonata for Piano, No. 28, Op. 101.

SCHUMANN: Toccata in C, Op. 7See Beethoven: Sonata for Piano, No. 28, Op. 101.

STAMITZ, C.: Sinfonia concertante for Violin, Viola, and Orchestra, in I).* STAMITZ, A.: Concerto for Viola and Orchestra, in B flat.

Josef Suk, violin'; losef Kodousek, viola; Suk Chamber Orchestra, I lynek Farkas, cond. (Milan Slavicky, prod.( SUPRAPIION 1 110 2626, $9.98.

Stamitz is a good name in music history, but there was only one great Stamitz Johann, father of the two brothers represented here. (Never mind the Czech spelling given on this Czech recording: They were as thoroughly German composers as Lully was French; the two sons were even horn in Mannheim.) Carl (1745-1801) and Anton (1750-1809?) were products of the late Mannheim school. Though they show the basic traits of the style and technique created by their father-and how they savor those long rolling crescendos-they definitely subscribe to the gulant/enip/itidsam movement, which in their heyday was already anachronistic. There is no trace here of loharn's venturesome, pathhreaking, and fierce spirit that so impressed Beethoven, who borrowed from him, among other things, the entire plan for the Fifth Symphony scherzo. (See review on page 49.) Anton, whose works are still little explored, seems on this evidence the more accomplished composer. His concerto sounds well and moves well, the string writing is adventurous, and the viola's range of color is admirably exploited. He hears investigation. Carl, on the other hand, should be put hack on the shelf. This sinfonia concertarte is not an original, but an arrangement (by the modern publisher)

from a double concerto for oboe and bassoon. Though well made-all of the Stamitzes were good musicians-it is epigonous, old-fashioned, and without any personal traits. Look at the dates: Carl was thirteen and Anton eighteen years younger than Haydn, and both apparently outlived Mozart (who, in his catty way, called Carl "a wretched scribbler") by many years, yet in style they lagged behind by a whole generation.

The performances and the sound are very good. Violist Josef Kodousek is a first-class artist with a fine tone and sensitive articulation; violinist Josef Suk is also capable, though not quite in Kodousek's class, and his tone is a hit too sweet. Conductor Hynek Farkac knows his business, and the orchestra is lively and precise.

STRAUSS, R.: Also sprach Zarathustra, Op. 30. Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, cond. ¡john Willan, prod.] ANGEL. DS 37744, $11.98 (digital recording).

Glenn Dicterow, violin; New York Philharmonic, Zubin Mehta, cond. (David Mottley, prod.' CBS MASTERWORKS IM 35888, $14.98 (digital recording). Tape: HMT 35888, $14.98 (cassette). BRH Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Richard Strauss, cond.

EVEREST 3475, $4.98 (mono) (recorded in concert, 1944; from OLYMPIA 8111, 1975).

COMPARISONS: Haitink/Concertgebouw Phi. 6500624 Kempe/Dresden St. Orch. Sera. S 60283

Although Richard Strauss's Nietzschean tone poem may never have been a special favorite of concert audiences and conductors, it long has been the prime choice for demonstrating the sonic potentials of new recording technologies. The sensational first version, from January 1935, by Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony in a 78-rpm set, was the earliest example of RCA's improved techniques of what it called "higher fidelity" recording.

Then the first stereo version, March 8, 1954, by Reiner and the Chicagoans, was even more of a historical milestone, for it was recorded experimentally by a now unjustly forgotten engineer, Leslie H. Chase, working separately from the regular "orthophonic" mono engineer; this pioneering stereo venture appeared first only on a 1955 two-track open-reel tape. The 1954 mono disc release wasn't supplemented by a stereo disc edition until 1960-one later reissued and still available as RCA Victrola VICS 1265.

The now legendary popular cult apotheosis of Also Sprach Zarathustra (or more specifically, its brief opening "Sunrise" pages) came in 1968 through its use in the soundtrack of the hit film 2007: A Space Odyssey, even though that excerpt was drawn from the not particularly spectacular 1959 DG recording by Bohm and the Berlin Philharmonic (136 001). The next significant sonic advance came in the first quadriphonic recording in 1973, by the late Rudolph Kempe and the Dresden State Orchestra, a version that still ranks high as a notably virile and authoritative interpretation. And now, a bit later than might have been expected, we get two examples of the very latest-digital-recording technology.

Angel's, the first released, is also the most spectacular, sonically, to date. Never have greedy sound fanciers been given more of their fill of biting brass, impactful timpani, and thunderous climaxes with floor-shaking bass-drum rolls. Reproduced full out on a big home playback system, this is the perfect lease breaker. My ears still ringing and my heart thumping hard, I have to lament, however, that such electrifying-indeed, near stupefying-sonics should have been generated for so crudely sensational a reading as Ormandy's. This one is faster, but even more mannered and episodic and laxer in grip, than his earlier versions for CBS (M 31829) and RCA (ARL 1-1220). And it sinks even deeper into unabashed emotionalism with exaggerated tempo and dynamic contrasts. Everything is larger and more grotesque than life. Accompanying the formidable powers of digital technology unleashed here are such concomitant weaknesses as the painfully sharp high frequencies and the absence of ambient warmth. The violin soloist (Norman Carol?) is mercifully unidentified: Surely, he and the other Philadelphia string players have never sounded like this in actuality! Mehta and his New Yorkers, in more genuinely realistic (Soundstream) sonics, give a more straightforward reading-one unexpectedly much more tautly controlled than in his pretentious 1969 London recording with the Los Angeles Philharmonic (CS 6609). The highs are razor-sharp, to be sure, but they don't draw blood from one's eardrums; and the miking, less excessively close, captures at least a bit of reverberance. Mehta also maintains an admirably consistent rhythmic pulse, with proportions well planned overall, and brings out the first of the midnight chimes that usher in the score's climactic "Night Wanderer's Song." (Too often these low-E tubular-chime strokes become only gradually evident when one can't see the percussionist in action.) Nevertheless, the many merits of the Mehta reading and its powerful yet crystalline sonics (to say nothing of the near ideal Mastersound disc processing), like those of several first-rate earlier analog Zarathustra recordings, pale in comparison with the most satisfactory, natural, and realistic sounding of all versions--Haitink's with the Concertgebouw (December 1974). This is also the most magisterial, lucid, and illuminating interpretation, with the finest solo violin playing by Herman Krebbers. Indeed, Haitink impresses me as perhaps the only Zarathustra conductor who has read and pondered Nietzsche s book. While his is a truly philosophical, even otherworldly, conception of the work, it does justice not only to its grandiloquence, but also to its playful and even humorous moments.

Haitink never forgets that, among Zarathustra's more sibylline sayings, he also asked, "Who among you can at the same time laugh and be exalted?" and asserted, "I should only believe in a God that would know how to dance." I suppose there must be at least a word for the eminently forgettable Everest release. If so, it's "Ignore!" The processing possibly may offer a fractional improvement over that of the 1975 Olympia version, but the reproduction remains intolerably distorted. That's not just from age, either, since the original wartime recording (in an empty hall, probably on Magneto phone tape for later broadcast use) of the composer's own historically invaluable reading sounds much more tolerable in far more satisfactory processing in Vanguard's five-disc set (SRV 325/9) of all the works in the Vienna Philharmonic's June 1944 celebration of Strauss's eightieth birthday.

VERDI: Un Ballo in maschera.

CAST:

Amelia Oscar Ulrica Riccardo Chief fudge Amelia's Servant Renato Silvano Zinka Milanov (s)

Stella Andreva (s)

Bruna Castagna (ms)

lussi Bjoerling (t)

John Carter (t)

Lodovico Oliviero (t)

Alexander Svéd (b)

Arthur Kent (b)

Samuel Norman Cordon (bs)

Tom Nicola Moscona (bs)

H--Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra, Ettore Panizza, cond. MET 8 (mono; three discs, automatic sequence) recorded from broadcast, December 14, 19401. Available with a donation of $125 or more (includes an Opera News subscription) to the Metropolitan Opera Fund, Box 930, New York, N.Y. 10023.

VERDI: Falstaff.

CAST: Alice Ford Raina Kabaivanska (s)

Nannetta Janet Perry (s)

Mrs. Quickly Christa Ludwig (ms)

Meg Page Trudeliese Schmidt (ms)

Fenton Francisco Araiza (t)

Dr. Cajus Piero de Palma (t)

Bardolfo I leinz Zednik (t)

Sir John Falstaff Giuseppe Taddei (b)

Ford Rolando Panerai (b)

Pistola Federico Daviá (bs-b)

A Vienna State Opera Chorus, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond.

PHILIPS 6769 060, $32.94 (digital recording; three discs, manual sequence). Tape: 7654 060, $29.94 (three cassettes).

COMPARISONS: Evans, Solti Lon. OSA 1395 Fischer-Dieskau, Bernstein Col. M3S 750 Gobbi, Karajan Ang. SCL 3552 Falstaff was in the typewriter when the Met Ballo tumbled in, and the timing seemed too good to pass up. What I was in the process of proposing is that Falstaff's reputation as a cerebral, "difficult" opera can be blamed on its performers, who--consciously or not--seem to like this state of affairs. Conductors especially get so wrapped up in the opera's detailing, concision, and layered complexity that they sort of assume these qualities are in themselves communicative.

The Falstaff performances I've enjoyed most have been those that treated the opera as a logical continuation of Verdi's earlier work rather than some radical departure. What this means mostly is hiring performers for their ability to make Verdi's musical gestures the logical and necessary expression of human urgencies, and this means singers with the range of developed vocal resources (with regard to range, dynamics, timbre, attack, etc.) you'd want for a "regular" Verdi opera.

Of course, this isn't exactly a radical idea; the Solti recording, for example, demonstrates what real voices can do for Falstaff (except in the title role, that is--an unhappy exception). But it dates back to the early Sixties, which prompts the question: When was the last time you heard a "regular" Verdi opera with real voices? In this connection, the Met Ballo is welcome for reasons that go beyond the obvious suitability of Milanov and Bjoerling to roles they never recorded complete commercially. Remember that this performance was no special offering, no grand marshaling of the troops; it was just another Saturday matinee at the Met-at a time, in fact, when the company was feeling tremors from the war in Europe. The Ballo was a new production, the Met's first in twenty-five years, but as John Freeman's historical note explains, the cast we hear was largely an expedient patchwork. Milanov and Svéd found their way into the opening night cast by virtue of the unavailability of Stella Roman (!) and Lawrence Tibbett, while Castagna was substituting in the broadcast for an ailing Kerstin Thorborg.

For that matter, although Bjoerling and Milanov were well established in, respectively, their third and fourth Met seasons, they weren't exactly legends yet.

What they brought to the occasion was a pair of healthy, flexible voices and the basic belief that it was their job to express character actions through singing. If your instinct is to say that one vocal department in which we're currently in not-so-bad shape is lyric tenors, compare Bjoerling's beauty and variety of timbre, elegance, ease, and expressive specificity with the recorded work of Pavarotti (London OSA 1398-hear in mind that this recording is vintage 1970, when his voice worked an awful lot better than it does now), Domingo (Angel SCLX 3762), and Carreras (Philips 6769 020). Like Falstaff, Ballo is to a large extent an ensemble opera, but here we're not apt to accept that the function of the ensembles is to submerge individual identities in some sort of collective abstraction; operatic ensembles make it possible to express an array of individual identities and agendas.

Yet if we switch to Karajan's Falstaff, we hear its admittedly complex ensembles dutifully pecked and chirped in a way that may be inoffensive to the ear but tells us nothing about the people involved.

On paper, Karajan's lineup looks like a shrewd response to the problems of casting the opera: for the older generation, a quartet of admired operatic veterans, Taddei, Panerai, Kabaivanska, and Ludwig (average age at time of recording: just over fifty-four); for the young lovers, a pair of smooth, pretty little voices; for the three character roles, singers with solid lists of credits. Not the strongest cast imaginable, but you figure, who knows? It could work.

And at times it does. Panerai remains a solid Ford, even if the voice shows its age alongside his delectable work in the first Karajan and the Bernstein Falstaffs--though I should add a word here for Robert Merrill's socko Ford with Solti. At least age hasn't dimmed Panerai's lyric-dramatic instincts, although it may be more to the point that the character doesn't submerge easily into ensemble amorphousness-so much of Ford's writing expresses impulses that simply burst into voice, almost into ra"ing. Panerai's response to the news of Falstaff's designs on his wife-"Sorveglierb la rrroglie. Sorveglieró it rrressere. Salvarvo' i beni rrriei dagli appetiti altrui"--is one of the rare instances in this recording of lines given fully voiced expression. But then, can these lines be performed any other way? Panerai's "Signor Fontana" scene with Taddei comes close to real dramatic life, and it's bracketed by a fine "Va, vecchio John" from Taddei and Panerai's predictably solid "E sogno." Taddei was nearly sixty-four when the recording was made, and it's a pleasure to discover how much survives of the finest baritone voice Italy has produced since the war. And yet, and yet.

Perhaps the mechanical quality of his performance is simply the price he has to pay to get through the role so "effectively"-a series of precise calculations of what the voice will and won't do. Or perhaps it's a response to the general quality of the proceedings, in which there are three kinds of singing: voice (what I would call "full voice" if these particular voices had such a formation), half-voice, and ha-ha. At any rate, too much of what he does here is tiresome fake-funny fat fool, much closer to the Falstaffs of Geraint Evans and Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau than to his own 1951 Cerra performance, still my favorite recorded Falstaff.

Further symptom: Kabaivanska, though she sings quite prettily, never establishes an identity independent of the other merry wives-a surprisingly bland performance from such an uncommonly interesting performer. Ludwig's Quickly is a surprise of a different sort: She sings the music surprisingly well. But it's done with mirrors. Okay, she manages to produce a clean sound below the break consistent with the rest of the voice, but that sound is such a slender wisp that she has nowhere to go interpretively. Interpretive possibilities require vocal capabilities-cf. Simionato (with Solti), Resnik (with Bernstein), or Barbieri (Karajan/Angel). Speaking of wisps, the fact that Nannetta and Fenton can be managed by the lightest of lyric voices doesn't mean that such voices can do them justice, especially in the face of such interpretive neutrality.

What game are the young folks playing? What do they want? How do they go after it? Verdi has provided the material for some wonderful answers to these questions; check out Freni and Kraus in the Solti recording-or, even better, the young Di Stefano in the 1949 Met broadcast conducted by Fritz Reiner. (Any chance the Met might give us that? The strong cast includes the likes of Warren in the title role, Valdengo as Ford, Resnik as Alice, Albanese as Nannetta, and Elmo as Quickly.) In fairness, I should note that the Philips performance is extremely neatly executed. But can't we take this for granted? If you undertake to record Falstaff, don't you warrant that you can get the notes more or less right? So can't we skip to the important questions, like what are those notes about? The near absence of any audible answer to this question is only compounded by Karajan's slow range of tempos, which simply stretches out the musical space that has somehow to be filled. The little "Reverenza" motif, for example, as played by the Vienna Philharmonic violins and violas and sung by Ludwig, seems to last for minutes rather than seconds-minutes that stretch into eternity as nothing happens. Maybe the digital recording has something to do with the colorlessness of the Vienna strings (compare the same orchestra under Bernstein), but then, Karajan has accomplished this feat on records before without such help.

Even De Palma's presence doesn't liven up the show as much as I'd have hoped. Unlike Bardolfo, which he sang so delectably for Solti, Cajus needs to make a big sound, which De Palma probably couldn't do now even at tempos more realistic for him than Karajan's. Zednik is a solid Bardolfo, his Germanic Italian notwithstanding; Daviá, a poorish Pistola.

If the Cetra Falstaff were available, I'd make this simple recommendation: Get it and the Solti; between them they do just about everything terrifically. Bernstein is wonderful too, in some ways even more interesting, but his cast is spottier. If London were to reissue its disc of excerpts with Corena in the title role, that might help plug Solti's and Bernstein's title-role gap. Alternatively, there's the Karajan/Angel set with Gobbi and a livelier cast than the Karajan/ Philips'. As for the Met Ballo, detailed comment and comparison seem beside the point, given its special provenance. Svéd is a stiff but solid Renato; Castagna, a fine UIrica; Andreva, a presentable Oscar. Cordon and Moscona make a robust pair of conspirators. The sound, clearer and less congested than on my pirate edition (not surprisingly, this performance has circulated widely in the underground), casts Panizza's conducting in a more favorable light: Except for his habit of speeding up and banging climaxes, this is a sane, lovely piece of work. There is one textual oddity: Riccardo's "Ma se m'i, forza perderti" was omitted in this production.

If you can afford the contribution, you'll enjoy this recording. If you can't, you're missing something-perhaps for the first time in the Met series. Cheer up, though; for $17.94 list, you can get the terrific Votto/La Scala Ballo with Callas, Di Stefano, Gobbi, and Barbieri (Seraphim IC 6087).

-----------

Critics Choice

The most noteworthy releases reviewed recently.

BACH: English and French Suites, S. 806-17. Curtis. TELEFUNKEN 46.35452 (4), Jan.

BEETHOVEN, MOLAR I : Keyboard Works. Bilson. Nonesuch 1171377, N 78004, Feb.

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No.6, Op. 1,8. Stuttgart Klassische Philharmonic, Munchinger. INTERCORD INT 160.828, March.

BRAHMS, BEETHOVEN: Clarinet Trios. Pieterson, Greenhouse, Pressler. Philips 0500 670, Feb.

BRAHMS: Orchestral Works and Concertos. Furtwangler. EMI ELECTROLA IC 140-53420/ 6M (7), April.

BRAHMS, SCHUMANN: String Quartets. Guarneri. RCA ARI 3-3834 (3), April.

BYRD: Motets (10). Byrd Choir, Turner. Philips 9502030, May.

CELIBIDACHE: Der Taschengarten. Stuttgart Radio, Celihidache. INTERCORD INT 160.832, May.

CLEMENTI: Piano Sonatas (3). Horowitz. RCA ARM 1-3689, May.

CORIGLIANO: Clarinet Concerto.

BARBER: Essay No. 3. Drucker, Mehta. NEW l\'oRI o NW 300, April.

GOLDMARK: Die Künigin von Saha. Takács, lerusalem, Fischer. HUNGAROTON SLPX 12170/82 (4), April.

HAYDN: Great Organ \lass. Academy of Ancient Music, Preston. OISEAU-LYRE DSLO 563, March.

MAHLER: Symphony No.6. Chicago Symphony, Abbado. PG 2707 117 (2), April.

MASSENET: Le Roi de Lahore. Sutherland, Lima, Milner, Bonynge. I ono 3LDR 10025 (3), Ian.

MUSGRAVE: A Christmas Carol. Virginia Opera, Mark. MMG 302 (3), May.

POULENC: Songs (complete). Ameling, Gedda, Sénéchal, Souzay, Parker, Baldwin. EMI FRANCE 2C 1h5-16231/5(5), May.

STRAVINSKY: I e Sacre du prinlenlps (arr.). Atamian. RCA ARC 1-3636, April.

TAKEMITSU: Instrumental Works. Tashi, Boston Symphony, Ozawa. DG 2531 210, March.

DENNIS BRAIN: Unreleased Performances. ARABESQUE 8071, May.

FERNANDO DE LUCIA: rhe Gramophone Company Recordings, 1002-9. RUBINI RS 305 (5), Dec.

EZIO PINZA: The Golden Years. PEARL GEMM 162/3 (2), Feb.

POLIINI: Piano Music of the Twentieth Century. PG 2740 229 (5), March.

Rosza, WAXMAN, WEBB: Film \lusic. ENTR'ACTE ERM 6002, March.

-----------

-------------

(High Fidelity, USA print magazine)

Also see:

The Critics Go Speaker Shopping [June 1981]