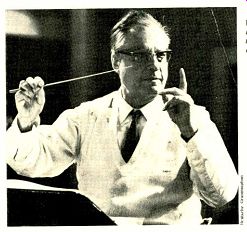

KARL BOHM: His reading captures the genial good spirits Schubert's Second symph.

By MARTIN BOOKSPAN

FRANZ SCHUBERT'S SYMPHONY NO. 2

SCHUBERT'S Second Symphony is a perfect illustration of the degree to which the Basic Repertoire has expanded in recent years. John Barbirolli conducted the symphony in New York with the New York Philharmonic in November 1936; that performance very probably was the first in America for this work. Boston audiences didn't hear it until December 1944, when Dimitri Mitropoulos performed it as guest conductor with the Boston Symphony. Today, of course. Schubert's Second Symphony is a beloved staple of concert life every where in the western world.

Schubert composed the symphony in the early months of 1815. He was then just eighteen years old, but he had al ready had nearly two hundred songs published, including such gems as Gretchen am Spinnrade, Der Erlk onig, An den Fr ohling, and Heidenrtislein. In the word's of Lawrence Gilman, Schu bert had already proved himself "a lyric and musico-dramatic genius, by the grace of God." But the first six of Schubert's symphonies, written between 1813 and 18 I 8, were produced rather casually, principally for informal performance by his friends and fellow students. No less an authority than Johannes Brahms edited the Schubert symphonies for their publication in the composer's collected works, and in the numerous manuscript changes made in the autograph scores Brahms found "significant evidence of the freshness and unconcern with which Schubert planned and even wrote his works."

The Second Symphony, in B-flat, bubbles over with ideas and with melodies, and its form and structure are remarkably secure considering the composer's lack of experience as a symphonist. It begins with a somewhat solemn ten-bar introduction that is marked largo and is reminiscent of the introduction to Mozart's E-flat Symphony, No. 39. The movement proper is marked allegro vivace , and its principal theme is a fleet and exuberant romp for the strings. The slow movement, marked andante, is a theme and variations with a concluding coda. The minuet, allegro vivace, has the heavy, foot-stomping character of a peasant dance. The trio contrasts nicely, with the oboe assigned the principal theme the first time around and the clarinet taking it up in imitation. The finale, presto vivace, returns us to the rhythmic propulsion of the opening movement.

-----------

Albert Roussel once wrote of this finale:

To my mind the final presto contains the most interesting passages of the whole sym phony. The first bar of the opening theme of this presto later gives opportunity, towards the middle of the movement, for a development of rather Beethovenian character, but original and daring and evidently contemporaneous with the writing of the Erlkonig. It is also noteworthy that the second theme of this movement, in E-flat, is repeated at the end in G Minor. So we see that Schubert already in his early works makes a habit of departing from classical traditions.

---------

OF the more than half-a-dozen different available recorded performances of Schubert's Second Symphony, my own favorite is the one conducted by Karl Bohm (Deutsche Grammophon 2530216: reel L 3216; cassette 3300216). With the Berlin Philharmonic in superb shape and the recording engineers providing luminously clear, for ward sound, Bohm delivers a reading that captures the genial good spirits and lyric flow of the music. His tempos are particularly well chosen- a shade on the restrained side in the first and last movements, but the restraint serves only to heighten the coiled-spring tension of the music. Those for whom Bohm's control may seem overdone are directed to the performance conducted by Karl Munchinger (London STS 15061, reel L 80038, cassette A 30661). Here the first-and last-movement tempos are brisker, the forward motion altogether more headlong than in the Bohm performance.

Since Munchinger has at his command the players of the Vienna Philharmonic, there is no danger of out-of-control propulsion, but the recorded sound is more cavernous than I would like. One distinct advantage Munchinger's version has over Bohm's, however, is in the matter of price: Munchinger's once full-price disc is now available on London's budget-price Stereo Treasury label at a list of $2.98 (compared with the Bohm list price of $6.98). Balancing this advantage for some listeners may be the question of couplings: Bohm's performance is on a disc that has an equally successful account, by the same forces, of Schubert's First Symphony; Munchinger, on the other side of his disc, offers a rather romanticized account of Schubert's "Unfinished" Symphony.

None of the other available recordings can really compete in distinction with either Bohm's or Munchinger's, though the performance conducted by the late Istvan Kertesz (London CS 6772) is straightforward, honest, and dependable.

Mr. Bookspan's 1973-74 UPDATING OF THE BASIC REPERTOIRE is now available in pamphlet form. Send $ 0.25 to Susan Larabee, Stereo Review, 1 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016 USA for your copy.

-------------

Also see:

CHOOSING SIDES--The Private World of Glenn Gould, IRVING KOLODIN

RAYMOND LEPPARD--A scholar-performer who hears-and understands--his critics.