"Critics don't matter if your schedule is full"

By Robert S. Clark

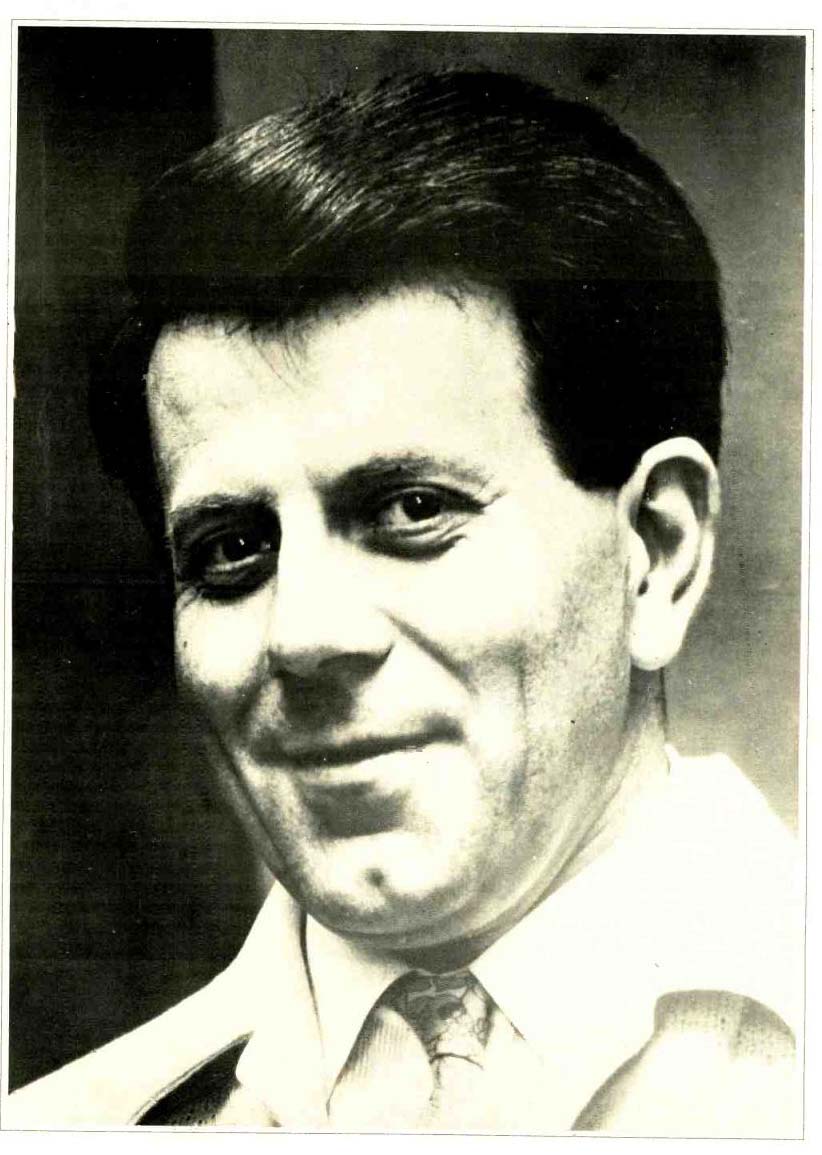

"I am a romantic, you see, and that is why I am fond of I early seventeenth-century Venetian opera. It is immensely passionate and moving." Raymond Leppard makes this statement with such conviction that a music lover unfamiliar with Venetian opera of that period would wonder what he has been missing all these years. When I talked with him, the dapper, dark-haired English musician- harpsichordist, conductor, teacher, musicologist, sometime composer- was in New York to conduct a pair of concerts at Lincoln Center. But on this side of the Atlantic, Leppard is probably best known not as a concert artist but as a scholar whose performing editions of the operas of Claudio Monteverdi and Francesco Cavalli have caused brisk tempests in the musicological teapots of several nations.

The objections to Leppard's realizations of Venetian opera chiefly take two forms. One British critic spoke for a considerable body of opinion when he deplored "the intrinsic discrepancy between the substance of the music and the performing style in which Leppard chooses to clothe it." The same critic coined the scornful term "musical ivy" for those "languorously intertwining added melodies" that Leppard writes for the instrumental parts of the scores, which survive only in skeletal form. Other commentators have complained about his cuts, revisions, transpositions, and the like. His reply to all this is candid and unabashed. "Well, my critics probably have a point, in their way," he said. "But my realizations are all de signed for effectiveness before contemporary audiences--just as the original productions were. These scores- Monteverdi's L'Incoronazione di Poppea, Cavalli's L'Ormindo and La Calisto--exist for the most part only as vocal and bass lines, and the sinfonie and dances in them as just a few bars for strings hurriedly written down by the composer and left perhaps for one of his students to complete. In those days the composer was al ways in charge at performances, and there was a lot of rehearsal time. The parts that were not written out in advance were improvised during rehearsals. These were like jam sessions: the composer would say keep that or don't, and the instrumentalist would scribble down some thing to remind himself. The whole thing was put into final shape in much the same way a musical is done today: numbers were scrapped or rewritten, cut or expanded, shifted from one scene to another. So I believe my methods have some precedent. The trouble with the academic mind-and I ought to know," he said with a grin, "for I've got one--is that it is trained to regard any surviving score as an Urtext. You can't do that with the Venetian operas. Ideally, if we were to re-create seventeenth-century conditions, we should realize these operas fresh for every performance. But of course that is impossible today." Why did the practical methods of the Venetians give way? "Commercial pressures brought about the change, I think. By the 1670's the new genre of opera had caught on everywhere in Europe. and it became impossible for the composer to be on the scene for every performance.

So scores had to be written out in full for publication. Of course, this facilitated the spread of the new form, and it made it a lot easier on the composers, too, as witness Cavalli's experience in Paris. By 1660, his fame had be come so great that Cardinal Mazarin asked him to com pose a new work for the young King Louis XIV's forth coming wedding. Cavalli, who was fifty-eight, was reluctant to make the journey to Paris, but-it was a great honor, and he at last decided to do it. Mazarin died shortly after his arrival, and the composer was left to the tender mercies of Lully, who was ballet-master at the court and surely the bastard of all time. Lully's maneuvering managed to put down Cavalli's work, and at the same time insured a good reception for his own ballets. Cavalli was so discouraged that he vowed never to write for the stage again.

After publication of musical works became necessary, at least composers did not have to go through experiences like that.

To return to the subject of my critics, I think they generally complain that I over-romanticize in my editions. But Monteverdi and Cavalli wrote very romantic music. I may have been anachronistic in some details, but I think my attitude toward the style is right. Look at the pictorial art of the time. It is very sensual, very concerned with the flesh. Those nudes of Rubens, for example they look as though they are asking for it. This music must be done passionately, particularly by the singers, and I don't think a plink here and a plunk there support a singer well enough for him or her to sing passionately." Anyone can form his own opinion of Leppard's work, for his realization of Cavalli's La Calisto is on Argo ZNF 11/12 for all to hear. In this recording Leppard conducts members of the London Philharmonic Orchestra and the Glyndebourne chorus, and Janet Baker doubles as the goddess Diana and as Jove taking the form of Diana in order to seduce the nymph Calisto (one of Diana's retinue). Even on records, without the visual aspect, the work is diverting and affecting musical theater. Diana's--the real Diana's--lament "Non e crude!, ben mio" in the first act, sung by Miss Baker, is ample demonstration that Leppard succeeds in inspiring singers to passionate utterance. The recording was made after a Glyndebourne production of 1970 in which Leppard collaborated with his old friend Peter Hallformer director of the Royal Shakespeare Theater at Stratford-on-Avon. Leppard, who has worked with Hall for many years (he composed incidental music for productions at Stratford), speaks admiringly of the director.

"Peter is fascinated by the problems of seventeenth-century opera. He has a keen ear for music and understands what musicians are trying to do. He never gives up when his approach is not working: he is adaptable and open to change, and will work until things come right.

Calisto was an example--the Jove--as-Diana business. The manuscript shows Jove's part written in the bass clef and Jove-as-Diana's in the treble. It seemed to us originally that the same singer should do both parts. We looked round and found Ugo Trama, an Italian bass with an absolutely marvelous falsetto. But as we rehearsed I became more and more uncomfortable about it. One day I asked a few members of the Glyndebourne musical staff to sit in on a rehearsal. When Trama did Jove-as-Diana, they roared with laughter. Trama was not consciously making a campy effect with the music, but it came off that way. Do you know the recording? Then you know that these passages are genuine love music--Jove is quite smitten with Calisto and wants very badly to take her to bed. That night I didn't sleep very well for thinking about it, and the next morning I told Peter I thought we ought to ask Janet to sing the Jove-as-Diana passages. He had come to the same conclusion. He was willing to scrap what he had done and start over.

"Of course, we needed Janet's consent. We called her, and, being a sensible Northern girl [Miss Baker was born in Yorkshire], she did not accept at once, but said, 'Give me five minutes to think about it.' Five minutes later to the second she called back and said yes. We were saved from what I really think might have been disaster."

Peter Hall likewise directed Leppard's realization of Monteverdi's opera II Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria, a new Glyndebourne production in the summer of 1973. Again the principal singer was Janet Baker, in the role of Penelope. "She is superb. It's a long part, and it may be the finest thing she has yet done. We won't record it, unfortunately. Two recordings are available in England, Nikolaus Harnoncourt's and another--I can't remember the details, but it is a mediocre old set on a low-price label.

When our production was announced, the latter suddenly began to sell quite well. My record company didn't want to risk putting another recording into the field." But even without Ulisse, he has recently spent-and will spend-a lot of time in the recording studio, much of it with Miss Baker. Philips has released their recording of Handel's cantata Lucretia and a group of Handel arias, and in the wings is their disc containing Haydn's sceno Berenice and Sesto's arias from Mozart's Clemenza di Tito, both with Leppard leading the orchestra, coupled with Haydn's cantata Arianna Abbandonata and Mozart songs, Leppard playing the fortepiano to accompany Miss Baker. In addition, they hope to compile a disc of Gluck arias. For Philips, too, he will finish recording all of Monteverdi's madrigal books, a project begun auspiciously with the five-disc album of Books V III and IX (6799 006) and continued with the just-released Books III and IV. He will also record Bach's harpsichord concertos, conducting from the keyboard.

Raymond Leppard's interest in Baroque music was born early and nurtured during his undergraduate years at Trinity College, Cambridge, particularly by Boris Ord, who was director of the King's College Chapel Choir when Leppard was a student. After his graduation he stayed on for a couple of years to do research, and then went to live in London. In 1953 and 1954 he was an assistant conductor at Glyndebourne, and soon thereafter was accepting guest-conducting engagements. In 1958 he successfully bridged the gulf between the academic and the performing worlds by becoming associated with the English Chamber Orchestra and at the same time returning to Trinity College as a Fellow and Lecturer in Music.

In 1962 he made the first of his realizations for Glyndebourne, Monteverdi's L'lncoronazione di Poppea, a production that has remained one of the festival's most popular (Leppard's version is also in the repertoire of the New York City Opera). He followed that with Cavalli's L'Ormindo in 1967, La Calisto in 1970, and Ulisse last year. He is currently at work on Cavalli's L'Egisto for the Santa Fe Opera's 1974 summer season.

Over the past couple of years his conducting career has taken on new importance. In 1971 he led two Mozart operas, Cosi Fan Tutte and The Marriage of Figaro, at Covent Garden. "It was not my first time on the Covent Garden rostrum. I did a staged version of Handel's oratorio Samson there a long time ago, with Jon Vickers. Joan Sutherland, who was then just coming to prominence, sang 'Let the bright seraphim' and made a sensation with it at every performance. But frankly I wasn't ready then for such an assignment. I enjoyed doing the Mozart last season very much- Covent Garden is a very well-run theater and a pleasure to work in. I had fine casts: Geraint Evans was Alfonso in the one opera and Figaro in the other, Kiri Te Kanawa was the Countess, and Ileana Cotrubas Susanna. Do you know Cotrubas? In my opinion she is the finest Susanna in the world today."

- - - -

ANOTHER assignment is drawing him further from the academy and more and more into the performing world.

With the 1973-1974 season he assumed leadership of the ninety-member BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra in Manchester. A glance at the repertoire listed for the sea son, which includes such names as Mozart, Beethoven, Shostakovich, and Tippett, shows that he is determined not to let his preoccupation with the seventeenth century dictate his program-making for the orchestra. I wondered if he expected his audiences to find it difficult to accept standard orchestral repertoire from someone who has a specialist's reputation. "Oh, inevitably I'll encounter something of that kind, perhaps more so from critics than from audiences. There is tremendous pressure on musicians to specialize, but I don't think we should. I love nineteenth-century music, and I think I have something to bring to it, because your insights into music of one period help to illuminate that of another. I expect I might face something like what Pierre Boulez has faced here in this country--though, of course, Boulez is not a romantic, and I am. But he is an extraordinarily talented conductor. His Debussy is like seeing light through a prism, all its color spread out in a spectrum. Yet the critics have at him, it seems, because he is not Bernstein. Why should anyone think Boulez would conduct Beethoven the way Bern stein does? Critics often assume a pose in relation to certain artists-after all, they have got to have something to say after each concert. That is not to deny that we can learn from some writers. But it takes you a while to make yourself immune to criticism, and for the young musician it can be harmful. I prefer to rely on the judgment of a few friends I know to be musical and perfectly honest as well.

If I've given a bad show they will tell me so. And, frankly, to come right to the point, critics don't atter if your schedule is full!"

-----------------

"Peter is fascinated by the problems of seventeenth-century opera. He has a keen ear for music and understands what musicians are trying to do. He never gives up when his approach is not working: he is adaptable and open to change, and will work until things come right.

"Calisto was an example-the Jove-as-Diana business. The manuscript shows Jove's part written in the bass clef and Jove-as-Diana's in the treble. It seemed to us originally that the same singer should do both parts. We looked round and found Ugo Trama, an Italian bass with an absolutely marvelous falsetto. But as we rehearsed I became more and more uncomfortable about it. One day I asked a few members of the Glyndebourne musical staff to sit in on a rehearsal. When Trama did Jove-as-Diana, they roared with laughter. Trama was not consciously making a campy effect with the music, but it came off that way. Do you know the recording? Then you know that these passages are genuine love music-Jove is quite smitten with Calisto and wants very badly to take her to bed. That night I didn't sleep very well for thinking about it, and the next morning I told Peter I thought we ought to ask Janet to sing the Jove-as-Diana passages. He had come to the same conclusion. He was willing to scrap what he had done and start over.

"Of course, we needed Janet's consent. We called her, and, being a sensible Northern girl [Miss Baker was born in Yorkshire], she did not accept at once, but said, 'Give me five minutes to think about it.' Five minutes later to the second she called back and said yes. We were saved from what I really think might have been disaster." Peter Hall likewise directed Leppard's realization of Monteverdi's opera II Ritorno d'Ulisse in Patria, a new Glyndebourne production in the summer of 1973. Again the principal singer was Janet Baker, in the role of Penelope. "She is superb. It's a long part, and it may be the finest thing she has yet done. We won't record it, unfortunately. Two recordings are available in England, Nikolaus Harnoncourt's and another--I can't remember the details, but it is a mediocre old set on a low-price label.

When our production was announced, the latter suddenly began to sell quite well. My record company didn't want to risk putting another recording into the field." But even without Ulisse, he has recently spent-and will spend-a lot of time in the recording studio, much of it with Miss Baker. Philips has released their recording of Handel's cantata Lucretia and a group of Handel arias, and in the wings is their disc containing Haydn's sceno Berenice and Sesto's arias from Mozart's Clemenza di Tito, both with Leppard leading the orchestra, coupled with Haydn's cantata Arianna Abbandonata and Mozart songs, Leppard playing the fortepiano to accompany Miss Baker. In addition, they hope to compile a disc of Gluck arias. For Philips, too, he will finish recording all of Monteverdi's madrigal books, a project begun auspiciously with the five-disc album of Books V III and IX (6799 006) and continued with the just-released Books III and IV. He will also record Bach's harpsichord con certos, conducting from the keyboard.

Raymond Leppard's interest in Baroque music was born early and nurtured during his undergraduate years at Trinity College, Cambridge, particularly by Boris Ord, who was director of the King's College Chapel Choir when Leppard was a student. After his graduation he stayed on for a couple of years to do research, and then went to live in London. In 1953 and 1954 he was an assistant conductor at Glyndebourne, and soon thereafter was accepting guest-conducting engagements. In 1958 he successfully bridged the gulf between the academic and the performing worlds by becoming associated with the English Chamber Orchestra and at the same time returning to Trinity College as a Fellow and Lecturer in Music.

In 1962 he made the first of his realizations for Glynde bourne, Monteverdi's L'lncoronazione di Poppea, a pro duction that has remained one of the festival's most popular (Leppard's version is also in the repertoire of the New York City Opera). He followed that with Cavalli's L'Ormindo in 1967, La Calisto in 1970, and Ulisse last year. He is currently at work on Cavalli's L'Egisto for the Santa Fe Opera's 1974 summer season.

Over the past couple of years his conducting career has taken on new importance. In 1971 he led two Mozart operas, Cosi Fan Tutte and The Marriage of Figaro, at Covent Garden. "It was not my first time on the Covent Garden rostrum. 1 did a staged version of Handel's oratorio Samson there a long time ago, with Jon Vickers. Joan Sutherland, who was then just coming to prominence, sang 'Let the bright seraphim' and made a sensation with it at every performance. But frankly I wasn't ready then for such an assignment. I enjoyed doing the Mozart last season very much- Covent Garden is a very well-run theater and a pleasure to work in. I had fine casts: Geraint Evans was Alfonso in the one opera and Figaro in the other, Kiri Te Kanawa was the Countess, and Ileana Co trubas Susanna. Do you know Cotrubas? In my opinion she is the finest Susanna in the world today."

ANOTHER assignment is drawing him further from the academy and more and more into the performing world.

With the 1973-1974 season he assumed leadership of the ninety-member BBC Northern Symphony Orchestra in Manchester. A glance at the repertoire listed for the sea son, which includes such names as Mozart, Beethoven, Shostakovich, and Tippett, shows that he is determined not to let his preoccupation with the seventeenth century dictate his program-making for the orchestra. I wondered if he expected his audiences to find it difficult to accept standard orchestral repertoire from someone who has a specialist's reputation. "Oh, inevitably I'll encounter something of that kind, perhaps more so from critics than from audiences. There is tremendous pressure on musicians to specialize, but I don't think we should. I love nineteenth-century music, and I think I have something to bring to it, because your insights into music of one period help to illuminate that of another. I expect I might face something like what Pierre Boulez has faced here in this country- though, of course, Boulez is not a romantic, and I am. But he is an extraordinarily talented conductor. His Debussy is like seeing light through a prism, all its color spread out in a spectrum. Yet the critics have at him, it seems, because he is not Bernstein. Why should anyone think Boulez would conduct Beethoven the way Bern stein does? Critics often assume a pose in relation to cer tain artists-after all, they have got to have something to say after each concert. That is not to deny that we can learn from some writers. But it takes you a while to make yourself immune to criticism, and for the young musician it can be harmful. I prefer to rely on the judgment of a few friends I know to be musical and perfectly honest as well.

If I've given a bad show they will tell me so. And, frankly, to come right to the point, critics don't matter if your schedule is full!"

-------------

Also see: