TESTED THIS MONTH:

Hitachi SR-5200 Receiver

Grado FTR+1 Phono Cartridge

Bib Model 45 Record Cleaner

Akai GX-285D Stereo Tape Deck

Hitachi SR-5200 Receiver

THE Hitachi SR-5200 is a compact, low-priced stereo receiver with considerable control and operating flexibility.

The dial scale, which occupies the upper half of the front panel, has illuminated words identifying the program mode and source selected (STEREO, PHONO, AUX, FM, AM), two tuning meters with zero-center and relative-signal-strength indications, a pushbutton power switch, and a large tuning knob. The lower half of the panel, finished in satin gold, has four knobs-BASS and TREBLE tone, BALANCE, and VOLUME. Pulling out the BALANCE knob switches the receiver to mono on all inputs, and pulling out the volume-control knob activates the loudness-compensation circuit.

Two pushbuttons independently connect the two sets of speaker outputs.

Other pushbuttons control tape monitoring for two tape decks (it is possible to dub from TAPE I to TAPE 2), turn on the FM interstation noise-muting circuit, and select the desired program source. There is also a stereo headphone jack on the panel.

In the rear of the SR-5200 are the in put and output connectors (TAPE 1 uses standard phono jacks; TAPE 2 has a high impedance DIN connector). A switch near the phono-input jacks changes the gain of the phono-preamplifier stages to accommodate high- and low-output phono cartridges. If the speakers connected to the remote-output terminals are placed in the back of the room, a SPEAKER MATRIX Switch in the rear of the receiver connects them to an internal matrix (essentially the familiar "Dynaquad" circuit) for simulated four-channel reproduction from two-channel sources. There are also antenna terminals for AM and FM antennas (the AM ferrite-rod antenna is inside the cabinet and is not adjustable in its orientation), an a. c. line fuse, and a single un switched a. c. convenience outlet. The Hitachi SR-5200 is supplied in a walnut wooden cabinet measuring 17 1/4 inches wide, 153/8 inches deep, and 53/8 inches high; it weighs just under 20 pounds. Price: $269.95.

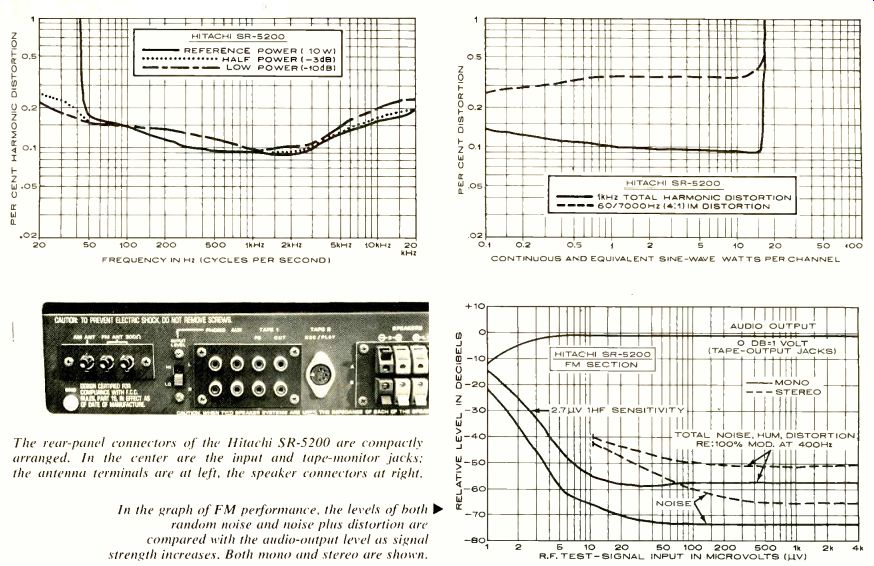

Laboratory Measurements. Our measurements indicate that the rated power output of the Hitachi SR-5200 (20 watts per channel) is based on only one channel's being driven, as is the case with many moderate-price receivers. With both channels driven by a 1,000-Hz test signal, the outputs clipped at 18 watts per channel into 8 ohms, 21.7 watts into 4 ohms, and 12 watts into 16-ohm test loads. The 1,000-Hz total harmonic distortion (THD) with 8-ohm loads remained almost constant at a low 0.1 percent from 0.1 watt to slightly over 15 watts, increasing sharply to 0.65 percent at 17 watts. The intermodulation distortion was about 0.35 percent over the same power range, and did not increase significantly even at the extremely low output power of 1 milliwatt.

As one might infer from its physical weight, the Hitachi SR-5200 has a relatively small power transformer. This is suited to normal music-reproduction requirements, but, under test, the receiver is not able to provide full sustained output power at the lower audio frequencies. At a 10-watt power level (which we selected as a realistic "maximum" when rating the unit across the full audio-frequency band), the THD was between 0.09 and 0.2 percent from 45 to 20,000 Hz, but rose rapidly at lower frequencies. At a 5-watt output, the THD level above 50 Hz was approximately the same as at 10 watts, but the measurements could then be extended down to 20 Hz, where the distortion still remained less than 0.3 percent.

-----

FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND) CONTNUOUS AND EQUIVALENT SINE-WAVE WATTS PER CHANNEL

The rear-panel connectors of the Hitachi SR-5200 are compactly arranged. In the center are the input and tape-monitor jacks; the antenna terminals are at left, the speaker connectors at right.

In the graph of FM performance, the levels of both random noise and noise plus distortion are compared with the audio-output level as signal strength increases. Both mono and stereo are shown.

--------------

The Aux inputs required 0.21 volt for a 10-watt output, with a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N) of 81 dB. The phono sensitivity could be switched to either 3.8 (HI) or 1.9 millivolts (Lo), with respective S/N measurements of 74 and 77 dB. All of these S/N figures represent superior performance. Phono overload occurred at 80 millivolts (HI) and 42 millivolts (Lo).

We do not envision any problems with phono overload in this receiver, but as always the HI (that is, lower-sensitivity or lower-gain) input setting should be used unless the phono volume is inadequate because of the use of a low-output phono cartridge. The AUX inputs could also be overloaded, but this requires an input of 4.6 volts, which is unlikely to occur in practice.

The tone controls provided a boost of 10 to 12 dB and 10 to 15 dB cut at the frequency extremes. The "flat" frequency-response setting had a slight roll-off at the lowest audio frequencies to -2 dB at 30 Hz and -5 dB at 20 Hz. This appears to be a wise precaution against the possibility of overloading the amplifiers at frequencies where their power-output capabilities are limited. Also, the rolloff serves incidentally as a very effective rumble filter with virtually no audible effect on music frequencies. The loud ness compensation boosted both low and high frequencies. RIAA phono equalization was within +2,-1 dB of the 1,000-Hz reference level from 30 to 15,000 Hz.

The FM tuner of the Hitachi SR-5200 had mono performance that was surprisingly good for a receiver of its price. The IHF sensitivity was 2.7 microvolts (µV), and 50 dB of quieting was obtained with only a 3.7-µV input. The FM distortion was between 0.1 and 0.2 percent at all levels above 10 µV, which we would consider excellent performance for a far more expensive product. The ultimate quieting was a very good 73 dB.

In stereo FM-the tuner switched from the mono mode at 11 µV-harmonic distortion was about 0.3 percent above 100 µV. This figure is also far lower than we have measured on most FM tuners, and the S/N was a good 65 dB.

The other stereo FM characteristics of the SR-5200 were equally noteworthy. The frequency response was flat within ±0.5 dB from 30 to 15,000 Hz, yet the 19-kHz pilot-carrier leakage was down 60 dB from full modulation. The stereo separation was excellent, averaging about 47 dB (±2 dB) from 400 to 11,000 Hz, and exceeding 23 dB over the full 30- to 15,000-Hz range. The FM muting threshold was about 11µV, and it produced moderate noise bursts when tuning across a signal.

The capture ratio of 0.8 dB also ranks with the best we have seen, and the AM rejection was a good 56 dB. Only in its selectivity characteristics did the SR-5200 reveal itself as a low-to-moderate price receiver. Alternate-channel selectivity was 38 dB on the high side and 43.5 dB on the low side of the desired channel; image rejection was 49 dB. The AM tuner had the expected limited high-frequency response, and it also had a low-frequency roll-off. The maximum output was at 2,000 Hz, and the output fell to -6 dB at 200 and 4,600 Hz.

Comment. Considered as a whole, the Hitachi SR-5200 is an honestly rated and flexible receiver at an attractive price. Compensating for the few cases in which our measurements fell slightly short of Hitachi's specifications (for the amplifiers), there were at least as many (for the tuner) where it far exceeded its published ratings, and actually outperformed the FM sections of some receivers costing twice as much. And those readers concerned about durability should note Hitachi's three-year guarantee on parts and labor.

The instruction manual, generally complete, does little more than mention the use of the built-in speaker matrix for simulated four-channel sound. Since there is no independent level control for the rear speakers, it is important that they be of approximately the same efficiency as the front speakers. We found the addition of rear speakers produced a pleasing effect, supplying a welcome sense of ambience with most stereo pro gram material.

Obviously, in some difficult receiving situations (such as when there is very low signal strength, or problems with alternate-channel interference problems), the Hitachi SR-5200 might not be the best possible choice. And one should not expect any relatively low-powered receiver such as this to fill a large room with the sound levels of a live performance, especially if low-efficiency speakers are used. However, we believe that the SR-5200 can fully satisfy the needs of the vast majority of listeners.

Used with two (or four) speakers in the $60 to $100 price range, plus comparable record playing and/or tape equipment, it should acquit itself admirably and provide audibly first-rate performance in almost all domestic listening circumstances.

Grado FTR+1 CD-4 Phono Cartridge

THE new Grado FTR+1 phono cartridge designed for playing CD-4 discrete four-channel records avoids sever al of the problems previously associated with such cartridges. These include high price, critical mounting tolerances, and the need for unusually low capacitance in the connecting cables. The FTR+1 is a magnetic cartridge with a user-replaceable 0.5-mil spherical (conical) diamond stylus. A major difference be tween this cartridge and virtually every other magnetic cartridge currently on the market is the very low inductance of its internal coils--only 50 millihenries in stead of the usual 700 to 1,000 millihenries. Because of this, its frequency re sponse is essentially independent of load resistance and capacitance. In contrast to other CD-4 cartridges, which require very short special cables for connection to the demodulator (and cannot be used at all in some record players because of high capacitance within the tone arm it self), the FTR+1 will perform with the capacitance equivalent of up to ten feet of ordinary shielded phono cable and with any phono-input load exceeding 10,000 ohms.

The rated signal output of the FTR+1 is 2.3 millivolts, which is somewhat lower than the output of most stereo cartridges but typical of today's CD-4 units.

Its rated frequency response is 10 to 40,000 Hz ±-2.5 dB, and the recommended tracking force is between 1 and 2 grams. Price: $11.95.

Another Grado model, the FTR+2, provides equivalent performance at the same price, but it is designed for tracking forces of 2 grams and above, making it more compatible with inexpensive record players.

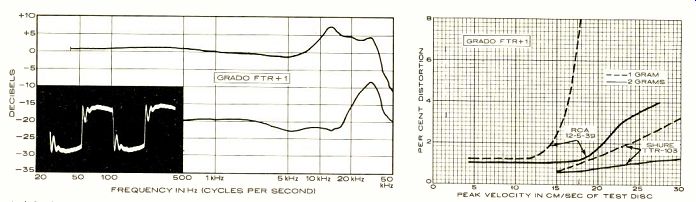

Laboratory Measurements. The out put of the Grado FTR+1 was about 2.1 millivolts with a test-record velocity of 3.54 centimeters per second (cm/sec). It tracked the very high-level (30 cm/sec) 1,000-Hz test signals of the Fairchild 101 test record with only slight clipping of the signal peaks at 1 gram, and with no clipping at 1.5 grams tracking force.

Very high-level 32-Hz test bands were tracked easily at 1 gram. The cartridge response to the 1,000-Hz square waves of the CBS STR 111 record showed two cycles of damped ringing at about 15,000 Hz (15 kHz). For frequency-response tests, we used a new test record from J VC, the TRS-1005, which sweeps from 1 to 50 kHz. We measured an impressive ± 3 dB up to 43 kHz, with response down only 5 dB at 50 kHz. The channel separation exceeded 25 dB up to 15 kHz, and was 12 to 20 dB in the range of 20 to 50 kHz.

These measurements were made with our standard cartridge load of 47,000 ohms paralleled by 250 picofarads (which would be far too much capacitance for any of the other CD-4 cartridges we have tested). Adding another 250 picofarads to the load had no measurable effect on the frequency response, even at 50 kHz.

The high-frequency tracking ability of the FTR+1 was measured with the Shure TTR-103 test record using its 10.8-kHz tone bursts. Tracking was very good even at a 1-gram stylus force and was even better with 2 grams. For the middle frequencies, we used the 400/4,000-Hz mixed signals of the RCA 12-5-39 intermodulation (IM) distortion test record. The IM distortion was a low 1 to 1.2 percent up to about 12 cm/sec at either 1 or 2 grams, but increased rapidly at higher velocities with the lower force.

At 2 grams, the IM was under 4 percent (very good) at all velocities up to the 27.1-cm/sec limit of the record.

In a listening test with the Shure TTR 110 record, using a 1-gram force, there was slight mistracking of the recorded bells and drums at the highest level and of the sibilant test at the three upper levels. With the force increased to 1.5 grams, the cartridge tracked everything except the highest level of the vocal sibilants, and even that very demanding section could be tracked at 2 grams. Very few cartridges we have used can match that performance at any force, and all are much more expensive than the FTR+1.

Comment. The Grado FTR+1 can be judged either as a stereo cartridge or as a CD-4 cartridge. As a two-channel cartridge, it ranks with a handful of the finest, all of which sell for four to six times its price. For playing CD-4 records, our sample was the equal of any cartridge we have used. Many popular record players and tone arms have too much wiring capacitance for satisfactory CD-4 performance (occasional "shattering" distortion caused by high-frequency carrier loss is the most common sign of excessive capacitance), but the FTR+1 per formed beautifully with more than eight feet of shielded cable.

Other CD-4 cartridges operate best with 1.5- to 2-gram tracking forces. The FTR+1 can do a fine job at only 1 gram, but for this we found it necessary to have very precisely adjusted anti-skating compensation. Also, when using some of the earliest CD-4 demodulators, we not ed the need for excessively critical adjustment of the demodulator as well as the player's anti-skating system, al though increasing the force to 1.5 grams sometimes helped. On the other hand, when we used two late-model CD-4 demodulators (with a greater ability to recover the 30-kHz carrier), there were no problems at all, even at 1 gram.

To check the effect of the FTR+1's 0.5-mil spherical stylus on record wear, we repeated the test we made in our initial evaluation of CD-4 equipment (STEREO REVIEW, December 1973). A short section of the inner portion of a CD-4 disc was played one hundred times in succession with a 1.5-gram force, while we monitored the level of the disc's 30-kHz carrier at the cartridge output. The level dropped about 3 dB in the first forty or fifty plays, and after one hundred plays it fluctuated between 3

------------

FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND); PEAK VELOCITY N CM/SEC OF TEST DISC: PEAK VELOCITY N CM/SEC OF TEST DISC

At left, the upper curve represents the averaged frequency response of the cartridge's right and left channels. The distance (calibrated in decibels) between the two curves represents the separation between channels. The oscilloscope photograph of the cartridge's response to a 1,000-Hz square wave is an indication of the cartridge's high- and low-frequency response and resonances. At right, the distortion of the cartridge for various recorded velocities of the RCA 12-5-39 IM test record and the I0.8-kHz tone bursts of the Shure TTR-103 disc are shown. The frequency-response and separation curves above were made with the CBS STR-120 test disc, not with the JVC disc cited in the text shown. The frequency-response and separation curves above were made with the CBS STR-120 test disc, not with the JVC disc cited in the text.

-------------

... and 10 dB below the original level. Even then, it was well within the recovery range of the demodulator, and there was absolutely no difference in sound be tween the played and un-played portions of the record. Our conclusion is that the FTR+ I will not significantly wear the grooves of a CD-4 disc in normal use, even at 1.5 grams.

The Grado FTR+1 has a notably clean, slightly bright sound. The apparent definition of the highest frequencies is striking, and some of this can probably be credited to the broad emphasis in the 10- to 20-kHz octave. There is another factor of equal importance, however. As we pointed out in "How Important Is Audio-Component Compatibility?" (STEREO REVIEW, January 1974), virtually all amplifiers have a loss of response at frequencies over 10 kHz when used with magnetic cartridges because of the effect of the cartridge inductance on the amplifier's RIAA equalization circuits. This loss, typically 2 to 4 dB in magnitude, occurs with most cartridge-preamplifier combinations, and will therefore rarely be noticed in comparative listening. The FTR+1, however, is essentially free of this effect because of its low inductance. This means that, with properly equalized preamplifiers, the extreme highs will be heard at their pro per level when this cartridge is used. We found the slightly bright sound of the FTR+1 to be highly listenable (never strident or overbearing), but if desired one could easily use the amplifier treble tone controls to make it sound more like other cartridges.

It should be obvious that the Grado FTR+1 represents a substantial break through in the price structure of high quality phono cartridges, as well as pro viding outstanding performance by any standard. Despite its low cost, the FTR+1 is not really suitable for use in the arm of an inexpensive record changer. The cartridge needs no more than 1 to 1.5 grams of operating force for good results, and this is too low for many inexpensive arms (for low-price record play ers, the Grado FTR+2 is a better choice).

In addition, for successful CD-4 operation, an effective and properly adjusted anti-skating system seems to be a must, and these are usually found only on the better players, those designed for tracking at forces below 2 grams.

Bib Model 45 Changer Groov-Kleen

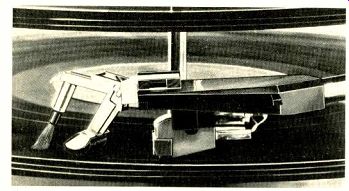

THE problem of keeping phonograph records dust-free is of legitimate and continuing concern to audiophiles, and it has inevitably resulted in the development of innumerable techniques and devices for that purpose. Some record cleaners are hand-held and are to be used just before play; almost all others are supported on separate "arms" that sweep the record continuously during play. However, none of these devices are suitable for those who, at times, prefer to play their records in stacks on a changer.

The Bib Changer Groov-Kleen Model 45 (imported by Revox Corp.) is meant to provide the groove-cleaning performance of the other designs without interfering with the normal functioning of a high-quality automatic changer. It can be installed easily on arms that have a flat pickup housing, and adapters are avail able for designs (such as the Garrard Zero 100) that do not have a suitable flat surface on their cartridge housing.

The Changer Groov-Kleen, molded of light plastic, consists of a tracking brush that rides on the record and a velvet pad that sweeps the surface between the brush and the cartridge stylus. The en tire assembly attaches to the end of the tone arm with an adhesive pad. The brush and velvet pad, which move freely in the vertical plane, are independently hinged and removable for easy cleaning.

A separate brush is supplied for that purpose, as well as for cleaning the cartridge stylus.

The Groov-Kleen assembly weighs 2 grams, although much of this weight is not added to the tracking force when the brush and pad are resting on the record surface. The installation instructions suggest alternative methods for recalibrating the tone arm for correct stylus force with the Groov-Kleen installed.

The Bib Changer Groov-Kleen Model 45 is priced at $3.95.

Comment. For test purposes, the Groov-Kleen was installed on the arm of a Dual Model 701 record player (the other Dual models use a similar cartridge housing). It appeared that, with most cartridges and most tone arms, the dimensions of the Groov-Kleen and its pivoted members would not interfere with correct cartridge mounting. Since the Groov-Kleen, when installed, does not extend appreciably above the top of the cartridge housing, in a properly ad justed record changer it should not con tact the bottom of a stack of records on the spindle. We determined that the best technique for resetting the tracking force to compensate for the Groov-Kleen weight was to rebalance the arm with the counterweight, so that the brush and pad rested on the record while the stylus just cleared the record surface. After this, the stylus force could be "dialed in" accurately in the normal fashion. Other tone-arm designs may require a different approach.

Using high-velocity test records, we found that, with the Groov-Kleen in use, the player's anti-skating dial should be set about 2 grams higher than normal for the selected tracking force. With a cartridge tracking at I gram, a 3-gram set ting of the anti-skating dial tested just about right. We determined that the Bib Groov-Kleen had no discernible effect on cartridge tracking or arm resonance.

Most of its slight mass is coupled loosely, if at all, to the arm during play. When we played our severely warped "test" record, which had previously caused mistracking on the record player, we noticed a slight improvement in resistance to lateral groove jumping. The stylus still left the groove, but tended to return to approximately the same point instead of (occasionally) entering an adjacent groove.

The Bib Changer Groov-Kleen Model 45 seemed to be an effective dust gatherer, although most of what it picked up appeared to be surface dust; we doubt that the tracking brush penetrated the record grooves significantly. The only inconvenience we noted in its use was the difficulty of seeing the cartridge sty lus for precise cueing. Of course, when a player is used as a record changer, this is of no importance. Overall, the inexpensive Groov-Kleen is a worthwhile addition to any automatic record-changing system. It helps solve the dust problem without introducing any undesirable side effects.

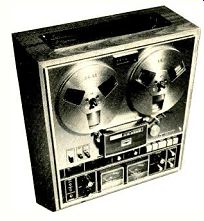

Akai GX-285D Stereo Tape Deck

THE Akai GX-285D is the first of that company's open-reel tape decks to have built-in Dolby B-Type noise-reducing circuits. It is a two-speed (3 3/4 and 7 1/2 ips), three-head, quarter-track stereo machine that accepts reels up to 7 inches in diameter. The GX-285D has provisions for bi-directional playback, tape reversal being initiated either by a strip of metal foil on the tape or manually by pushbutton. If foil is applied to both ends of a tape, the tape will cycle back and forth indefinitely.

The solenoid-controlled tape transport is operated by light-touch pushbuttons or through an accessory remote-control unit. It has three motors and a logic system that permits any mode to be engaged from any other without first pressing the STOP button (except for the RECORD function). The necessary time delays are built into the system, with the tape coming to a full stop and pausing for about a second when going from fast wind or rewind to normal speed. The reversing operation takes about 3 seconds. The playback head is shifted mechanically to pick up the recorded tracks in the re verse direction.

The GX-285D is equipped with Akai's glass and crystal ferrite heads whose shaped poles provide extended high-frequency response without the need for large amounts of high-frequency equalization when the deck is recording. A pushbutton switch optimizes the bias level for standard or low-noise tape formulations. Speed change is by push button, as is the selection of quarter track mono or normal stereo operation.

In addition to automatic end-of-tape motor shut off, the recorder can be switched to a full shut-down mode, in which the line power is switched off when the tape runs out.

The RECORD-interlock button, which must be pressed along with the FWD but ton to make a recording, is close enough to the transport controls for this to be a one-handed operation, yet not so close that there is any danger of engaging it accidentally. The PAUSE button (push to engage, push to release) stops and starts the tape almost instantly without releasing the record function.

Along the bottom of the control panel are the two 1/4-inch microphone-input jacks (for medium-impedance dynamic microphones) and a stereo-headphone jack for 8-ohm phones. Two large illuminated meters indicate recording and playback levels. There are separate microphone and line-input level controls (each of which is a concentric pair for individual channel adjustment) plus a concentric pair of playback-level controls. The microphone and line inputs can be mixed, or, by using the DIN input jack which goes through the microphone gain controls, one can mix two line sources. A pushbutton activates the Dolby system (there is a green indicator light), another connects each channel's playback output to the opposite recording input for sound-on-sound recording, and a third switches the line outputs to the source or to the playback amplifiers.

In the rear of the recorder are an un switched a.c. convenience outlet, a sock et for the remote-control accessory, and the line inputs and outputs (these are paralleled by a DIN connector, with a switch for use with amplifiers having different output levels). The Akai GX 285D, in its walnut cabinet, is about 18 x 17 x 10 1/4 inches and weighs about 48 1/2 pounds. Price: $750.

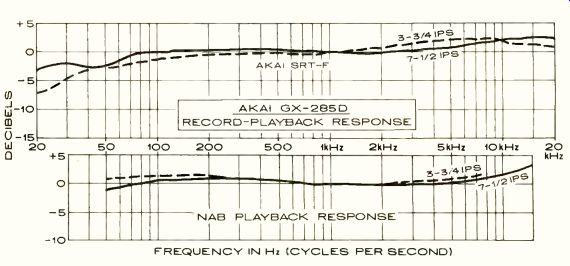

Laboratory Measurements. The Akai GX-285D is factory adjusted for Akai SRT-F low-noise tape, which we used in our tests. Other high-quality, low-noise tapes, such as Maxell U D35-7, gave similar performance. The playback response over the range of the Ampex NAB-standard test tapes was ±1 dB from 50 to 8,000 Hz at 7 1/2 ips, rising to +3 dB at 15,000 Hz. At 3 3/4 ips, the response over the range of the test tape (50 to 7,500 Hz) was-±0.8 dB. The frequency response was virtually identical in both directions of tape travel, indicating that the alignment of the mechanically shifted single playback head was accurate in both positions.

With the Akai SRT-F tape, the overall record-playback frequency response was an excellent ±3 dB from 35 to 23,000 Hz at 3 3/4 ips, and ±3 dB from 25 to 26,000 Hz at 7 1/2 ips. The claimed excellent high-frequency characteristics of the GX heads was illustrated by the fact that the response from 20 to 20,000 Hz was essentially the same at a 0-dB re cording level (!) as at the -20-dB level normally used for these measurements.

With a "standard-oxide" tape (3M-111), the overall response was still excellent: ±3 dB from 23 to 25,500 Hz at the 7 1/2 ips speed.

The "tracking" of the Dolby circuits was good over most of the audible frequency range. At a-20-dB level, the Dolby system had no affect on the over all record-playback frequency response.

At-30 dB, there was a minor boost of high frequencies, beginning at 4,000 Hz, with a maximum amplitude of 1.5 dB.

At -40 dB, the response above 9,000 Hz was increased to a not particularly significant maximum of +2.5 dB.

For a 0-dB recording level, a line input of 0.11 volt and a microphone input of 0.7 millivolt (mV) was needed. The microphone-preamplifier circuits overloaded at 45 mV. The 0-dB playback output level was 0.8 volt. The 1,000-Hz total harmonic distortion (THD) at 0 dB on the recording-level meters was 0.5 percent at 7 1/2 ips and 2 percent at 3 3/4 ips.

The standard-reference distortion level of 3 percent was reached at +5.5 dB at 7 1/2 ips and at +2 dB at 3 3/4 ips. The signal-to-noise ratios, referred to 3 percent THD, were 60.8 dB at 71I/2 ips and 56.7 dB at 3 3/4 ips. With the Dolby system in use, these figures improved to 69.2 and 64.3 dB, respectively. At maximum gain, the microphone preamplifiers added about 3 dB to the noise level.

The wow and flutter at 7 1/2 ips were 0.01 and 0.07 percent in either direction of tape travel. At 3 3/4 ips, they were 0.01 and 0.09 percent in the forward direction, and 0.02 and 0.11 percent in the reverse direction. All these figures are excellent for a machine of this type. The operating speed was virtually exact, and 1,800 feet of tape was handled in 95 seconds in wind or rewind mode. The level meters read-1 dB when playing a standard Dolby-level reference tape. The meters were slightly slower than true VU meters, reading about 80 percent of the steady-state value on a 300 millisecond tone burst (as compared with 99 percent for a professional VU meter).

The headphone volume should be satisfactory with most 8-ohm phones, but may be too low with higher impedance or low-efficiency phones.

Comment. The operation of the Akai GX-285D was flawless, and its tape handling was as nearly foolproof as could be desired. Even power shutoff during fast forward or rewind-that nemesis of so many other recorders brought the tape to a smooth, perfectly controlled stop. The reverse play is a welcome feature, and the time lag during reversal was not objectionable. The PAUSE control stopped and started the tape almost instantly, but there was a momentary "chirp" or wow of the signal on start-up. As with almost any pause system, this can be avoided by not activating the control while a signal is in the machine's circuits.

As our test data show, the Akai GX-285D is without question a first-rate home tape recorder. To provide a frame of reference: a top-quality cassette recorder with Dolby approaches the Akai's performance without its Dolby circuits switched on, except that the Akai does not suffer from the restricted high-frequency dynamic range of the cassette format. Switching in the Akai's Dolby system increases its dynamic range to the point where the major limitation is then the noise level of the incoming pro gram. And, of course, the Akai can be used to play Dolbyized pre-recorded tapes without the need for add-on accessories, and with truly impressive results.

FREQUENCY IN Hz (CYCLES PER SECOND)

----------------

Also see:

TECHNICAL TALK Is Phase Shift Audible?

PERFECTING SOUND REPRODUCTION--Are discs, tapes, and FM broadcasts as good as they might be?

TAPE HORIZONS--Bridging the Gap