ROCK & RICHES--The (economic) facts of life in the business of pop music.

Those kids are all making a bundle, right?

By Allan Parachini

The houselights sim and the clamor of the crowds falls to a low buzz- low enough that the anticipatory coughing can be heard amid the hum of the PA system. In a moment the show will begin. It makes no difference what band is about to play, and it doesn't matter where. What is about to be unleashed, like a genie out of a bottle, is an IMAGE- magical, mysterious, and glamorous one of many raised up by that energetic cultural force known as Rock, swathed in clouds of sumptuous glory, lauded in hymns of hyperbolic praise, and flattered by the proliferation of those smaller scale imitations known as Lifestyle. This pantheon of heroes and heroines has no parallel in contemporary culture, and we must go back to the early days of the silver screen-of Valentino, Pickford, and Garbo- to find anything like it. What it is, is myth, a highly selective metaphor about life, of which both performers and their audiences, romanticized and romanticizing, are at, once creators and consumers.

But myths are like Chinese boxes, one nestling inside the other on into infinity. The myth immediately inside the myth of the Rock Star is that of Untold Riches, and there is just enough truth (though not much) to it to make it an effective mag net, drawing young people to New York, Los Angeles, Nashville, or wherever else music is made and recorded to declare themselves in on a piece of the action, a slice of the fabulous take.

They arrive in Los Angeles, for instance, by battered car or bus, check into the YMCA, and hit the street. They walk up to Yucca Street, or Vine near Hollywood Boulevard, look in the Yellow Pages under "Records," and start feeding change into a payphone. Then they wait, lounging on the sidewalk outside a liquor store, having given the payphone as "a number where I can be reached," for the return call that never comes. They have a common desire--a career in the music business-and a host of very uncommon, often highly original, misconceptions about just what that business is. They are, in short, as much prisoners or victims of their myth as any Forty-niner ever was, feeding their hopes on the good news of occasional rich strikes and ignoring the multitudinous evidence of failure all around them.

The J. Geils Band, they will tell you, slaved away, first as two separate groups and then together under the Geils name, for five years in Boston bar rooms before managing to land a record contract; they now average $10,000 to $15,000 a night. Black Oak Arkansas played insignificant dates throughout the South for four years waiting for what they finally got-a luscious contract with Atlantic Records.

Dr. John was an obscure New Orleans studio musician for ten years before a chance hit single miraculously transformed his career in 1973. Rod Stewart, who once slept on a Spanish beach because he couldn't afford a hotel room, who used to play professional soccer to support his music habit, now earns, by reliable estimate, between $750,000 and $1,000,000 annually. At the top, the money piles up like winter snow in Donner Pass, and the bulldog tenacity that keeps so many musicians struggling up the lower slopes is fueled by the expectation that they too will eventually, if only they hang on, get to frolic in it. What are their chances?

RECORD companies sold 1,436,000,000 (that's one and one-half billion) seven- and twelve-inch discs in the United States in 1973. There were 196 releases certified "gold" (meaning they sold 500,000 copies for an album, 1,000,000 copies for a single). Such figures translate very readily into Big Money, of course, and the myth has it that the musician is first in line to collect. And myth it is, for there are very few performers indeed in the most favored position.

The performer derives revenue primarily from two sources: live performances and record royal ties. He may also earn something from song-publishing royalties (if he writes his own material), since there will then be royalty income from others who perform his songs and from radio stations that play them on the air as well. But before the musician realizes any income whatsoever, he must normally commit a percentage of all his earnings "up front" to a manager, unless he is clever enough to handle his own business affairs- including negotiating complicated contracts with record companies and booking agents; insuring that the provisions of those contracts are fulfilled; securing the most favorable possible terms for such seemingly incidental arrangements as production, promotion, and marketing of records, travel provisions for performance tours, and even the reservation of recording studio time.

A few musicians are just adept enough at business to have come to the unwise conclusion that self-management is a realizable goal. Few reach it, and many budding careers are ruined each year because some overconfident youngster insisted he knew enough about the music business to fend for himself in the jungle of accountants, lawyers, and systems analysts who run modern record companies. Creedence Clearwater Revival was probably the most successful group in recent history that was actually self-managed, but John Fogerty, Creedence's leading light, had the benefit of powerful good advice from Saul Zaentz, president of Fantasy Records, the small Oakland, California, label on which Creedence appeared for the duration of its professional life and for which some of its individual members, including Fogerty, still record.

Poco's manager, John Hartman, put management in this capsule: "Management is not a person, it's a force that exists in the artist's consciousness. If the guy's manager tells him one thing and his old lady tells him another-and he listens to his old lady then the old lady is that force." For most musicians, a professional personal manager is an absolute necessity. Managers normally retain between 10 and 15 percent of the musician's entire gross income and can in some cases get as much as 20 or even 50 percent. Accountants (more and more indispensable the higher the sales figures get) are another accoutrement, and they get $200 to $500 a month.

Such people are necessary not only to help the per former retain a reasonable part of his initial gross, but also to interpret the complex financial systems that appear to be peculiar to record companies; they are needed to make certain the musician does not, plainly and simply, get screwed.

Managers are usually blamed for the failures, but they are seldom credited for the successes of the musicians they handle; they generally find them selves in the position of gamblers at a high stakes game- lose once and you're out. Peter Casperson, who owns Castle Music Productions, a small management firm in Boston, employs ten people to minister to the needs of four active acts, in which Casperson estimates he has about $50,000 invested.

One of the acts is Jonathan Edwards, whose top selling single Sunshine failed to reach first position in the Billboard sales charts two years ago only because American Pie got there first. The Edwards windfall from that single alone was sufficient reward for Casperson, who has stayed with Edwards (who frequently falls victim to a strong desire to move to the country and who dislikes the grueling pace of live performing anyway) since Sunshine was a hit.

But Casperson's operation is small potatoes in every respect when measured against such management "giants" as Los Angeles' David Geffen, whose stable includes more than twenty performers, from the Eagles to Linda Ronstadt.

Managers are not a race of white knights, of course. Their ranks are heavily populated by the shady and by the inept, either of whom can leave a client musician, in the manner of one of those bilked innocents in an old prize-fight movie, with no return whatever for his efforts, gold-record sales or no. Selection of a good (honest, capable) man ager is therefore one of the music business' biggest risks.

BUT to return to the question of income. Record royalties, unlike the fees paid for live performances, are established contractually between record companies and musicians for periods of between one and five years. Gross royalties are computed on a base of 90 percent of the whole sale (just over $2.00 for albums) or the retail ($5.98 average) prices of each record actually sold. Retail discount prices do not bear on royalties. The per former gets between 5 and 18 percent of 90 percent of retail, say (depending on the terms of his contract), and though there are several ways to compute the amount, they generally work out to about 42 cents per album. The record producer gets a 2 or 3 percent royalty, which may in some cases be deducted from the musician's share, and the a-&-r (for "artists and repertoire") man who signed the artist to a record contract in the first place frequently gets 2 or 3 percent, normally from the record company's gross.

Under the royalty system, the potential for income from a record that sells well is actually not bad (more than $200,000 for a gold album, for ex ample), and if a musician has written his own songs, he receives an additional gross of 1 1/2 cents per song, per record, in song-publishing royalties. Normally, the manager has unobtrusively procured for himself some of the publishing proceeds; if he is honest, he has also done as much for his client.

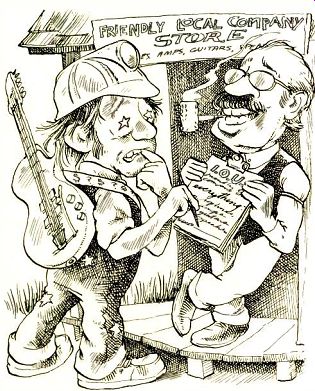

Otherwise, the naive musician may likely find that he has unknowingly signed away some or even all of the potential publishing income as part of a cash "advance" in an innocent-looking contract with a music-publishing firm or even his own record company.

Record companies have established what seems to be a unique sort of company-store relationship with their artists, one that tends to cut handsomely into the income potential of royalties. First, the record companies normally try to charge back to the artist as much of the actual cost of recording and marketing a record as possible. Such costs can amount to $15,000 or $20,000 (for the most mod estly produced album) to as much as $100,000 (for an overproduced spectacular). They include studio time, union pay for extra musicians, and other expenses too numerous and too unimaginable to mention-even the cost of the recording tape is levied against royalties. The record companies also charge their artists for some of the expenses of promoting and publicizing the resulting recording, including, for example, press parties and the cost (from $750 to $1,500 per month) of retaining a private publicist. A modest tour may also be underwritten by the record company-and charged against the royalty gross; even a short introductory series of engagements in small clubs can run to as much as $50,000.

What results is in many cases an arrangement that would be bitterly familiar to any old-time Appalachian coal miner. Some recording acts owe so much of their soul to the company store that they never overcome their indebtedness; they can only watch helplessly as the royalties of their successful later records are eaten up in mid-career by early advances. Then too, determining the number of copies of a record actually sold is a task of no little difficulty. Records are distributed on consignment, meaning that unsold goods may be returned-for full credit-by individual record stores to small distributors, by small distributors to large, and large distributors to the original record company. The consignment arrangement is a necessary one, since without it distributors and their clients would probably never gamble on a first release by an artist they had never heard of, or even on a great second release by someone who had bombed with his first.

The problem with this system is that it can take at least several months, and at times as much as several years, to determine accurately the exact number of copies of a recording sold. Record companies manage this situation to their advantage, often with holding a portion of royalties against the possibility of such returns.

Most record contracts stipulate that sales records may be audited, but the auditing process itself is one comprehensible only to an accountant with extensive experience in the business. "I always audit," says Casperson. "It's just part of the game with big record companies." Poco's Hartman agrees. "You find that if you audit, you turn up discrepancies. I don't think it's so much the result of blatant, intentional stealing as it is that the bookkeeping system is so complicated and the price structure so complex." Royalties are usually paid out only once every six months. For a group as battle-scarred and success fully established as Poco, whose albums regularly sell between 200,000 and 250,000 copies, the royalty hassle is little more than that, and one that will ultimately be amicably resolved. But for a struggling new act whose first album sold only 50,000 copies (or even 1,000 copies) the shock of meager royalty return (or none at all)- with the inevitable appropriate deductions-can be devastating, even mortal.

Special arrangements are frequently negotiated under which a manager or record company pays a weekly salary or underwrites the rent of musicians.

But what the performers usually seem to forget is that there must ultimately come a day of reckoning.

Scrupulous managers try to avoid the certain shock of the bottom line by establishing trust savings ac counts for client musicians. One semi-prominent English blues band's management, seeking to avoid the budgetary trauma that comes with the eventual end of the short earning life of his clients (it is, after all, somewhat shorter than that of professional athletes), has put $10,000 in a bank account for each of the four members of the group without their knowledge. Other managers, however, are content simply to break the news that there is no money, that advances have eaten up every cent.

To be successful, a group or solo performer must, of necessity, be caught up in a vicious circle formed and controlled by the whims of the fickle popular music market. Live performances are most profit able when they are booked simultaneously with the appearance (and the promotion) of a relatively new piece of recorded product. Conversely, it is difficult to develop an ongoing, steady market for the pur chase of records without spending a great deal of time On The Road (thus capitalized because of its rigors). The road's merciless, cold reality is of such awesome proportions that few performers who have been moving around the circuit for any length of time can resist writing a song or two about it, thus adding to its lore. (In this it is not unlike the musical theater, which is simply filled with works telling us there's no lifestyle like show business.) Janis Joplin, of course, died on the road; so did Jimi Hendrix and Cass Elliot. The road killed Jim Croce-and Buddy Holly, Patsy Cline, and many others. Poco's Tim Schmit has been saving his motel-room keys from the last two of his five years on the road, and they now half fill an enormous carton he keeps in a closet at home.

Live performances are usually arranged by a professional booking agent or by someone in the musician's management who fills the function of a booking agent. Agency work is dominated by about a dozen big firms with offices around the country.

Agents retain between 10 and 20 percent of the gross proceeds of live performances they arrange.

The fees paid for such performances is an area in which there simply are no norms. Rates are set either on a flat basis (so many dollars per performance, regardless of eventual audience size), or they are based on a combination of a cash guarantee and a percentage of the gross proceeds. Under the system, a group such as New Riders of the Purple Sage probably averages about $7,000 a night; the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band, which plays a murderous schedule of more than 200 one-nighters a year most of them before college audiences-between $5,000 and $10,000 a night. Only a tiny number of groups consistently earns more-and it is hard not to know just who they are.

Such sums may look rather impressive to the average struggling wage-earner, but gross figures are misleading-they do not take into account the expenses, the short earning lives of the musicians, or the years of near-starvation they put in before any one paid attention to them. Poco, for instance, has been a working, self-supporting, comparatively well-to-do group for only five years, the Nitty Gritty Dirt Band for seven. That makes both of them fairly senior in a business in which five to ten years is often required just to get established. The Dirt Band was playing high schools in the San Fernando Valley for $300 a night as late as 1966- and one must remember that that is not $300 every night. The reasonably good money lasts, in most cases, only two or three years. Groups as big as Creedence can, in those two or three years, amass a fortune. But members of a group of the stature of Blue Cheer, for example, which enjoyed a brief fling at the height of the San Francisco acid-rock movement, have long since faded into obscurity and (perhaps) poverty.

----------------------

Croesus

A group's first couple of years at the threshold of the Big Time are the most critical simply because they are most often fatal. The figures below represent an attempt to estimate, by the most liberal and optimistic of standards, what a "new" group might earn that first or second year out. It should be noted, however, that this optimistic reckoning, which is based on a realistic assess ment of potential, does not necessarily bear any relation to the experiences of an actual group averages seldom do. It should be noted too that the hypothetical group Croesus, for whom these figures were run up, would be--if it existed--a lot better off than some real groups. Croesus' income, meager though it is, is substantially higher, for in stance, than what the Kinks earned in their first twelve months as an entity in the United States.

Income

One album, selling 75,000 copies; royalties established at a rate to yield 42 cents per copy $31,500

One tour of forty-five engagements, at an average fee of $1,000 per performance $45,000

Total $76,500

Outgo

Advance on royalties from record company at signing of contracts (spent to purchase amplifying equipment, pay union dues, settle old debts, etc.) $ 5,000 Cost of recording first album 19,000 Manager's 15 percent of record royalties 4,725 Manager's 15 percent of booking proceeds 6,750 Road expenses (15 percent of gross) 11,250 Booking agent's share of live-performance revenues at 20 percent 9,000 Publicity agent for six months 6,000 Additional equipment expenses, normal wear and tear 5,000 Total $66,725

Net income $9,775

Croesus is a four-man band, sharing equally in all income. The net result for each member, under this very optimistic accounting $2,443.75

-----------------------

Even assuming a respectable pay scale, the tricks of survival on the road are learned only after bitter experience and (usually) the squandering of a great deal of money. For instance, a band must, of necessity, invest heavily in electronic equipment. The Dirt Band, which could not be said to carry an extraordinary amplification system, travels with 8,000 pounds of equipment valued at more than $50,000.

Even the least elaborate array of equipment sufficient to produce a respectable stage sound these days requires an initial investment of more than $20,000. Sometimes this money comes from the record company or management-another advance against royalties.

But the biggest hazard of the road (except for the constant problem of awakening in a strange Holiday Inn with no idea of the name of the city in which it is located) is that inexperience, incompetence, or both will result in most of the proceeds being spent even before the tour has been concluded. Managers and booking agents have varied theories about how much it should cost to live and travel on the road.

Poco's Hartman, for instance, figures costs of transportation, lodging, equipment shipping, insurance, and the like at about 25 percent of the gross from the tour. In the case of one Poco expedition a couple of years ago to a relatively "tight" cluster of 39 cities in 45 days, the 25 percent amounted to be tween $50,000 and $60,000.

Steve Miller, an established, almost universally respected musician who waited about ten years for the public to become aware of his prowess, frugally manages and books himself, holding costs to a bare-

bones minimum in the five months a year he's on the road. He figures the percentage at less than 10--with costs amounting to only about $21,000 for a recent tour that grossed $300,000. Miller travels modestly with a small party of eight, two of whom are equipment managers who normally drive trucks (which must be bought, gassed, repaired, and insured, by the way) laden with equipment while the rest of the entourage flies from city to city. Many groups, frustrated by the loneliness of the road, take friends and/or wives along on tour with them-a comforting touch of home, but it eats very quickly into the gross.

Bruce Nichols, a booking agent with Agency for the Performing Arts (APA) in New York City, sees Hartman's 25 percent figure as realistic and desirable as a norm, but he believes that, for many groups, expenses run as high as 50 percent and even higher. The differences are owing to a variety of reasons. "New" groups all too frequently fall prey to the temptation to spend unreasonably large amounts of money on expensive hotel rooms or even suites. Some rent limousines to drive from air ports to hotels and from hotels to auditoriums.

These indulgences may add a touch of glamour to relieve the strenuous life of the road, but they also absorb much of the money that should remain as earnings at the end of the tour.

Such considerations aside, the most important single factor in successful live booking is routing, the plotting of the course of the tour from day to day-or week to week. Ideally, a tour should be booked with no city farther than 250 or 300 miles from the one preceding it, and there should be only one day off per week. That way one avoids paying

$200 a night for motel rooms unnecessarily. Routing is a tricky thing to manage, even for a skilled professional booker. More than one group has met the fate of Taos, a small-time West Coast act which may have lost its chance at the big time after an agent arranged dates in two nearly contiguous California cities- separated by a one-nighter in Dallas! The internal financial structure of groups also has an effect on income. Some, like the Dirt Band, are legally incorporated, with members sharing the profits. Others, like the old Jeff Beck group, have one or two prominent members enjoying a share of the gross (in that case, Beck himself and vocalist Rod Stewart) and remaining members drawing merely a salary. There are shadings in these arrangements ad infinitum between.

An essential ingredient of life on the road is the road manager, or "roadie," as he is known. He is the one who keeps the group together, sees that they arrive on time, finds out why hotel reservations have been confused, flights canceled. Some groups absorb the functions of the roadie themselves. The Dirt Band's John McEuen, for instance, carries a banjo case in one hand and an airline schedule book in the other on tour, shifting roles according to demand. But, most often, the roadie (and his assistants, who move the equipment) is another separate employee who draws a salary right off the top.

Though it is true that there is a comfortable living to be made in music (from $50,000 to $100,000 a year) for a small number of anonymous, unglamorous studio musicians (usually older, always highly skilled), the performing musician whose name appears on records and concert billings is usually not nearly so well off. Groups in the middle area of prominence, like the Dirt Band and Poco, can, if management is competent, enjoy an upper-middle class income. Poco's Schmit, for instance, like many other musicians, is buying his own modest home. The individual members of the Dirt Band have earned as much as $40,000 in one year-but as little as $3,000 in many others. They cannot, therefore, compute an "average" because their musical and financial fortunes have simply been too widely spread.

More frequently, the rule of the game is that of performers like Sherman Hayes. Hayes, who is thirty years old, has been playing professionally since 1964. He comes from a family of musicians, so he was prepared for the lean times, especially those preceding the release last fall of his first Capitol album. Sherman is married, with a three-and-a-half year old son. He owns a 1958 Chevrolet panel truck and rents a small house in Hollywood. It costs him between $600 and $800 a month to live- probably more now. He is $8,000 in debt from earlier group efforts, but Hayes, his booking agent, and his record company have faith.

He went on the road for three months last winter, playing club dates for between $150 and $500 a week. His first album, as first albums will, did not sell spectacularly. Anyway, Capitol is figuring the recording costs and their sponsorship of the tour against royalties. Hayes paid two sidemen $175 a week each on the road. He crammed his equipment (the act is acoustic and requires only one amplifier) into two trunks. There was no money for a roadie, so Hayes and his sidemen horsed the trunks all along the route. "I'm losing my ass on this tour," he commented over coffee in New York one after noon. "I don't see how anyone can be in music and not be thinking about the fact that it is a business," Hayes said. "I'm just happy to be still on the label!" For people like Sherman Hayes, the lure of money is still rather farfetched, but the music is there, and for now it has to be a good part of the reward.

MUSICIANS are, in general, people of fragile egos and are often afflicted with a profound naivete.

Those who can learn to adapt to the business of music survive- sometimes- and a few, very few, can move beyond that to the Big Money. But, for the most part, what the uninitiated see when they look up from the orchestra or down from the balcony is an illusion. Those are not dollar signs, but just the beam of a Super Trouper spotlight reflecting off a guitar purchased through an advance against royalties.

Allan Parachini, formerly a staff writer for the Los Angeles Herald-Examiner, is now a resident fellow and visiting scholar at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.

============

Also see:

ROCK & RICHES--The (economic) facts of life in the business of pop music, ALLAN PARACHINI