by Irving Kolodin

THE BUDAPEST GODFATHER

THE reissue on the Odyssey label of a choice cross-section of Budapest Quartet performances from that group's prime period in the Fifties (Haydn's Op. 76 on Y3-33324; Beethoven's Op. 59, Op. 74, and Op. 95 on Y3-33316; Schubert's Op. 29, Op. 161, and Death and the Maiden on Y3-33320) is much more than an event welcome in itself, for it also provides a recorded link in the chain of chamber-music appreciation in this country, connecting the prior phase of it, represented by RCA's reissue of Flonzaley Quartet material a couple of years ago, with the ongoing tradition, represented by the latest Schwann listings of today's fine American quartets.

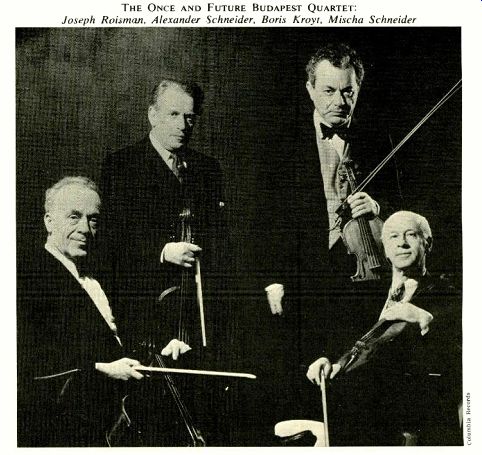

The Flonzaley heritage was unique (even for its time) in being the product of an eccentric-meaning that it was supported by a man of means who was also a devotee of chamber music. The Budapest accession, a decade later, to the position of prominence relinquished by the Flonzaleys in 1927 exemplified a totally different economic approach as well as a wholly individual aesthetic one. History tells us that a Budapest Quartet toured briefly in America in 1930, but it was not until 1937, when Alexander Schneider (second violin) and Boris Kroyt (viola) joined Joseph Roisman (first violin) and Mischa Schneider (cello), that America began to hear the Bud apest Quartet.

Against the still-echoing background of such elite groups as the Flonzaley (with its Franco-Italian conditioning), the Lener (authentically Hungarian, and the first to have a complete cycle of Beethoven quartet recordings issued in this country), the unforgettable London (with its refinement and warmth of temperament), the Roth (peerless in Mozart), and the Pro Arte (Franco-Belgian at its best), the Budapest, as newly constituted, had its detractors. It was held by some to verge on coarseness in its fervent pursuit of musical meaning; to stretch quartet sound to excess in its stress on equality of execution; to court vulgarity in making vibrato a strong, steady part of a warm ensemble sound rather than a color to be touched in with care. And as for welcoming a reigning jazz musician (Benny Goodman) to join in the recording of the Mozart Clarinet Quintet, wasn't that pushing lack of pomposity just a bit too far? But it is precisely the fervor, evenness of execution, warmth of sound, and lack of pomposity that make these performances as vital and alive today as on the day they were re corded. It was a "day" coincidentally equidistant from the real beginning of the quartet's American adventure in 1937 and its termination thirty years later. The precise median point would be 1952: fifteen years after its beginning, fifteen years before its end. The contents of these three Odyssey albums straddle the target year like well-placed bombs: the Beethoven a year before. the Schubert a year later, and the Haydn two.

----- THE ONCE AND FUTURE BUDAPEST QUARTET: Joseph Roisman, Alexander

Schneider, Boris Kroyt, Mischa Schneider.

This timing might be said to maximize the element of musical proficiency and to minimize the possible incursions of age. In any event, those fifteen years of preparation were sufficient for a concept of quartet playing to be converted into an actuality and for the three players who made the long journey all the way together to accommodate themselves to changing second violinists without audible alteration of the ensemble. In these performances that second chair is occupied not by Alexander Schneider, the one member of the 1937 quartet still active today, but by Jac Goredetzky. It was his illness (and death in 1955) that brought back Schneider, who was to remain with the group until it disbanded in 1967.

Nevertheless, these performances are " Budapest" in every detail: broadly swinging and forthright in the Op. 59, No. 1, of Beethoven; inimitably anguished but self-contained in the Schubert Death and the Maiden; marvelously sportive yet elegant in all six Haydns. Given such a heavenly high standard of quality throughout, I would shrink from recommending one set as preferable to another, but if I were challenged at pistol point to make a recommendation "or else," my favor would fall to the album containing the six Haydn quartets of Op. 76. This is not because they are "better" Budapest than the Beethoven or Schubert, but because they are least likely to be soon equaled or surpassed. We already have Beethoven performances by the Juilliard and Guarnieri Quartets which, in their own way, equal the strength of the Budapest performances of Op. 59 if not yet their insights, and the Cleveland Quartet's Death and the Maiden is something with which to reckon.

But the generally celestial standard of Buda pest performance is raised to an unmatched seventh heaven of sonorous splendor in the Haydn.

REHEARING these performances after twenty years is like revisiting a gallery to see a great painting and, standing back and apart from it, appreciating new values and subtleties. During its playing days, the Budapest member ship made much of its democratic rehearsal procedures, of not having a "leader" in the old Joachim, Kneisel, Rosé, Lener sense (a musical "dictator" to whom the others deferred).

Perhaps so, but when it comes to articulating the personality of a quartet, of responding to an eighteenth-century work the way an eighteenth-century composer wrote it, only one man can assume the responsibility. Call him the "leader" or simply the first violinist, the unassuming Roisman assumed that leadership with the right amount of authority and all the strength of purpose needed to give Haydn's musical profile its distinctive, quirky conformation. In Op. 76, No. 1, it is the solo in the trio of the Menuet to which he imparts just the properly roguish touch, much as, in the Pia presto of the finale of No. 4, he gives a delightful imitation of a man trying to oblige the composer by playing almost (but not quite) faster than he can. But he is also capable of a supernal sobriety, as in the hymnal slow movement of No. 3, the Emperor; I cannot recall ever having heard a performance more perfectly proportioned.

FOR those to whom these remarks may be merely affirmations of their own high regard for records already on their shelves, the over all release nevertheless holds an interest. That is a disc (Y3-33315) coupling previously unreleased performances (the forerunners of others to come, I am told) of the Franck Quintet (recorded in 1956) and the Faure Piano Quartet No. I (recorded in 1957). Like the others, these are Library of Congress performances with all the acoustical benefits that implies. And they were recorded "live." I doubt the Clifford Curzon would play a more resonant, forceful Franck today, or that Jesus Maria Sanroma, now living in Puerto Rico, would be in any finer form for the Faure.

The second violinist in these performances (which are undoubtedly more intensely Slavic than a Francophile would prefer) is Alexander Schneider, whose presence returns the quartet to its first, and to its last, form (save that Leslie Parnas replaced the ailing Mischa Schneider in its final three concerts). As individuals, its members brought a rare combination of unity and diversity to their work: all were Jews, all were Russian-born (Roisman and Kroyt in Odessa, the Schneiders in Vilna), all pursued their higher musical education in Germany. As a group they had a powerful effect on the playing of chamber music the world around.

The direct products of the quartet are the strongly emotional, highly disciplined, in tensely intellectual music-making of these totally typical and thoroughly remarkable discs. The by-products are no less remark able, for they are nothing less than the whole breed of today's supremely strong American string quartets. During a long period (1939 1949) in which foreign travel was all but ruled out, the Budapest Quartet was domiciled here, as active on the West coast as it was on the East. If the Juilliard Quartet (founded in 1945) can be said to be the father image to such groups as the Guarnieri, Cleveland, Fine Arts, La Salle, and Tokyo, the spiritual god father that set the standard they aspire to was surely the Budapest, the ensemble that was begun by Hungarians and ended up comprising four Russian-born, German-speaking American citizens.

Also see:

CHOOSING SIDES, IRVING KOLODIN

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)