By JAMES GOODFRIEND, Music Editor

SEEING MUSIC

As anyone who has gotten beyond the warm-bath stage of listening knows, there are many levels of sophistication on which one can hear, understand, and appreciate music. Although varying degrees of in born ability and learned knowledge are involved in how different people listen to music and how their listening habits change and develop, the purpose and the invariable result of more sophisticated listening is greater enjoyment and deeper appreciation. It is not just an intellectual thing. As Bernard Jacobson once said in describing his own method of music criticism: "The first part of criticism is the un conscious part: I simply watch my gut to see how it reacts. . . The intellectual part is the task of drawing the lines that connect the ob served event and the reaction." I bring this up as a method of fore stalling-temporarily, at least-the inevitable negative reaction of the non-musician to the suggestion that he look at a musical score.

"But I don't read music," is a perfectly understandable rejoinder to such a suggestion. I would counter by saying that you really don't have to read music to follow a score, and that the additional comprehension and enjoyment of the piece that will most likely result from doing so is worth far more than the small effort involved.

Of course, it's easier if you can read music.

But really, as recondite as a musical staff may appear to most people, dynamics are supplied in letters (ppp to fff, etc.), tempos are in words, time signatures are in numbers, and there are only three ways a melodic line can go: up, down, or sideways. Once you can associate hearing an upward movement with seeing an upward movement in an instrumental part, you have begun to follow a score. Of course, if you are following the score of a vo cal work, beginning is even easier: you can start by following the words.

Scores used to be either monster-size affairs--thick, heavy, and bound in cardboard--for conductors' use and costing the earth, or little yellow or grey affairs (miniature scores), often badly printed and invariably poorly bound, which you used to buy in the most un-swept corners of music stores.

Things have changed. For example, for a $7.95 cover price you can buy a handsome soft-bound volume (with a reproduction of a Fuseli painting on the cover), well printed in readable music type, and measuring about nine by twelve inches, that includes the complete orchestral scores of Mendelssohn's Midsummer Night's Dream music (all of it), he Hebrides Overture, Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage, and the Third and Fourth Symphonies. In other words, almost all of Mendelssohn's most important music for orchestra, reprinted from the original Breitkopf & Fliirtel edition of the collected works.

The same outlay will get you (in a similar-sized volume) the complete string quartets of--- Ludwig van Beethoven (also from the B. & H. edition), and for $4.50 apiece you can purchase two volumes offering, respectively, Schubert's C Major String Quintet, fifteen string quartets, and two string trios; and the Trout Quintet, the Adagio and Rondo Concertant for piano quartet, and the two piano trios plus the single-movement Notturno. These treasures (and treasures they are) are published not by a music publisher, but by Dover Publications, the same company that has marketed excellent and useful hooks in the fields of art, photography, craftworks, science, mu sic, and dozens of other subjects. Among their other scores are the complete quartets of Mozart, Brahms' string chamber music, Cecil Sharp's famous collection of one hundred English folk songs, the collected piano works of Scott Joplin, American songs of the 1890's, two volumes (in addition to the Joplin) of piano rags, a volume of Debussy's piano music, another of Gottschalk's, and so on.

Now, precisely what will one of these scores do for you if you follow it while listening to your favorite recording of that particular work? In essence, it will let you hear more of the music, much more, more, in all probability, than could be achieved by doubling your investment in reproducing equipment. The natural tendency of the human ear is to focus on one element of a complex sound--the highest, the loudest, or the most actively moving-accepting the rest as a sort of un detailed matrix. There are, therefore, things going on at any moment in music that we do not hear, or do not hear at first, and some of these may be of surpassing importance and interest. The "Russian" theme in the slow movement of Beethoven's Quartet, Op. 59, No. I, for example, is first stated in the cello.

But the cello's entrance is coincidental with a trill in the first violin, and the unwarned ear gravitates first to the violin (higher pitch and faster motion) and only later tumbles to the fact that the theme is elsewhere. This is by no means a particularly important example, but it is an obvious one. In the complexities of four part writing, all sorts of counter-themes, implications of things to come, reminiscences, and references remain buried, for unsophisticated ears, under the principal matter at hand. But there is far more to music than the uppermost theme (if there weren't, Rimsky Korsakov would be as great a composer as Haydn). and anything that aids us in hearing what else is there is contributing to our under standing and to our pleasure. Correct performance, well-balanced recording, topflight re producing equipment, and plain knowledge and listening experience all help. But the score is an inexpensive, easy, and enormously valuable aid in getting to the heart of things.

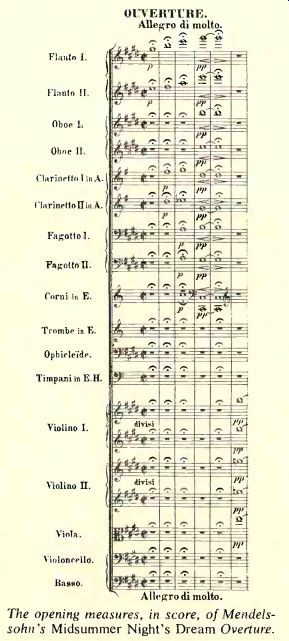

THERE is pleasure too in being able to see just how a composer has done something. The four opening chords of Mendelssohn's Mid summer Night's Dream Overture are invariably referred to as "magical." Their "magic" lies in their scoring, for each chord is scored differently. The first is for two flutes alone, the second adds two clarinets, the third adds two bassoons and one horn, and the fourth, which is marked pianissimo (the first three are marked only piano), adds the second horn and the two oboes. It does not lessen our enjoyment to actually see this. A kiss in the dark can be a pleasure, but the pleasure may be in creased if we know who we are kissing. And even if it is not, maybe that is better than hating ourselves in the morning.

-------- The opening measures, in score, of Mendelssohn's Midsummer

Night's Dream Overture.

Also see: THE OPERA FILE

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)