by STEPHANIE VON BUCHAU

IF it is true, as Frederic Grunfeld says in the preface to his Art and Times of the Guitar, that there are twenty mil lion guitars in circulation in the United States, then we must once again be in the grip of the passion that the French call "la guitaromanie." Since the guitar is one of the most difficult instruments to master-though anyone can easily learn to play a few chords-it is doubtful that even one million of those twenty million guitars are played well. Still, interest in playing the instrument naturally leads to interest in hearing it played. But here the young guitarist often runs into a mental roadblock. His contemporaries, while rightly applauding the talents of B.B. King, Eric Clapton, and John Mc Laughlin, tend to dismiss serious music written for the classical, or Spanish, guitar, a medium-sized, womanly-shaped, six-string instrument that is al ways played (by classical artists) with the fingers themselves, never with a pick or plectrum.

This dismissal is made partly out of ignorance, partly out of revolt against those music educators who insist, as though it were some evil-tasting medicine, that "classical music is good for you," and partly because the well-played classical guitar is so dulcet that some people automatically assume it is lacking in emotional depth. When I was first learning to play, I remember having my efforts dismissed by a fellow critic who complained that classical guitar music "had no guts." When the Western world became technologically oriented in the late nineteenth century, the popularity of handwork diminished and with it the popularity of the guitar, one of the very few musical instruments played directly with both hands with no intervening bows, keys, pedals, or other mechanical devices. Because of this decline in popularity, most of the existing repertoire of serious guitar music comes from an earlier period (roughly 1550-1900) when recognizable tonalities or modalities, prepared and re solved dissonance, and modest dynamics were the general rule.

For these reasons classical guitar music may seem to fervent modernists (classical or popular) to "lack guts," but that is just a mid-twentieth-century aesthetic position, not immutable fact.

The fact is that the instrument, which was played by Mary Queen of Scots, Catherine of Aragon, Henry VIII, Rossini, Schubert, Weber, and Berlioz, is capable of an enormous technical and emotional range which audiences, performers, and composers are coming more and more to recognize.

Andres Segovia, the acknowledged leader of the twentieth-century guitar revival, has inspired many Spanish and Latin American composers to write works for him. Julian Bream and John Williams have had the same effect on contemporary British composers. As composers become more convinced of the guitar's potentiality for serious musical expression, so do more performers. The increasing number of guitarists a generation younger than Bream and two or three generations removed from Segovia attests to this conviction.

Since there is nothing in armchair listening more stimulating than hearing someone play an instrument that you play yourself, recording companies readily see the wisdom of producing records (particularly records that don't cost a great deal to make) for the owners of those twenty million guitars.

Consequently, over the last several years there has been a marked increase in the number of classical guitar recordings released. Master instrumentalists naturally head the lists, but re cording activity is not limited to just the big names, for many young guitarists are being given a chance to show what they can do also.

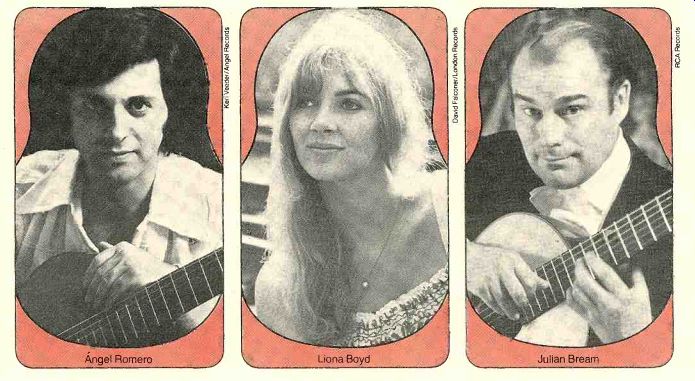

THOUGH he is just thirty, Angel Romero hardly qualifies as a "young guitarist"--he made his debut when he was six as soloist with Los Romeros, the family quartet which includes his father, Celedonio, and his two older brothers. Recently, Angel has made his solo recording debut with two important albums: "Classical Virtuoso" (Angel S-36093) and "Spanish Virtuoso" (Angel S-36094).

In the classical pieces Romero displays a crisp, bell-like tone. The big numbers in the album are Mauro Giuliani's Grand Overture, Op. 61 (Bream and Siegfried Behrend have also re semi-occasional recorded it), Fernando Sor's Variations on a Theme by Mozart, and a series of dances by Gaspar Sanz (1640-1710).

Romero's playing is less resonant than Bream's, but no less accurate. In the Grand Overture, where the bass consists of rapidly repeated notes, Romero manages to sound rather as if he had ten fingers on his right hand. Beethoven, who is reported to have called the guitar a "miniature orchestra," would have approved.

Sor's variations on "Das klinget so herrlich" from The Magic Flute are played with charm and a secure virtuosity, while the Spanish rhythms of the Sanz pieces are perceptively related to one another with musicianly under standing. The album also includes four Scarlatti sonatas transcribed by Romero from keyboard originals.

The "Spanish Virtuoso" recording is subtitled "Romantic Music for Gui tar," and Romero takes advantage of this invitation to reveal a seductive, honey-and-lemon tone. His rubato (those elegant hesitations that steal time from some notes and add it to others), his range of coloristic effects in pieces such as Albeniz's Cordoba and Granados' La Maja de Goya, and the slightly astringent harmonics in Turina's Fandanguillo are joined to technical virtuosity in Tarrega's Estudio Brillante, a work in which the treble melody floats serenely over swift bass figurations.

Angel also appears with his older brother Pepe playing Rodrigo's Concierto Madrigal on Philips 6500 918. It is a work written especially for the two brothers in 1968, and it is not so much a concerto as it is a series of variations on a theme-"Felices ojos mios" from an anonymous madrigal-which sets two guitars against a full orchestra, in this case that of the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields. Its yeasty Renaissance feeling is emphasized by brass fanfares, lively dance rhythms, and the variation in which the guitars are pitted against the piccolo, flute, oboe, and trumpet. The slow movement, Arleta, is perhaps too extended for some undup of new recording tastes, but Rodrigo's richly romantic string writing is as certain to appeal here as it does in the popular Aranjuez concerto.

Liona Boyd, blond and beautiful, smiles a Mona Lisa smile from the jacket of her debut album for London "Beethoven, who is reported to have called the guitar a 'miniature orchestra,' would have approved." Records ("Classical Guitar," CS 7015).

It is hard to believe she is for real until one looks at her hands. They are the hands of the serious guitarist: the long, bony, spatulate fingers and the prominent veins indicating that intense muscular development has pared away subcutaneous fat. Ms. Boyd plays the in evitable debut pieces, selections from Bach's Lute Suite in G Minor (BWV 995, transposed for guitar to A Minor) and Scarlatti sonatas (transcribed from the keyboard works), cleanly but in a rather subdued, "correct" manner, as if she were afraid to impose her own personality on such eminent masters.

But the album is more than rescued by the fact that most of it is devoted to un usual compositions by obscure contemporary composers: Julio Sagreras, Eduardo Sainz de la Maza, Joao Guimaraes, Francisco Calleja, and Henri Tomasi.

These delightful works, plus two Albeniz sketches, are vignettes depicting Spanish and Latin American life: hummingbirds, bells at dawn, Brazilian street dances, a mule driver in the Andes. Ms. Boyd discovers the individual character in each piece through her highly imaginative playing.

Her technique is flawless in rapid figurations such as the tremolo in Sainz de la Maza's Campanas del Alba or the one in Calleja's Cancion Triste. Her s sensitivity to color, her phrasing of the haunting melodies, her rhythmic vigor, and (particularly) her sweet tone are re corded with life-like fidelity.

Liona Boyd studied with Alexandre Lagoya, the great French guitarist whose "Viva Lagoya!" (Philips 6833 159) is one of the most stimulating solo albums I've heard in years. Like his pupil, Lagoya essays part of the Bach Lute Suite BWV 995 (the Prelude and Presto), but with all the difference in the world. Where Ms. Boyd is some what timid, Lagoya attacks with dash, élan, and exhilarating technical freedom, with the result that we hear every strand of the polyphony standing alone, we feel the rhythmic muscle and drive of the Presto. Bach is followed by a superbly mellow, mature performance of Handel's Sarabande in D (the title theme of Kubrick's film Barry Lyndon) and a magisterial reading of Silvius Weiss' Passacaglia, a dance form with variations on a ground bass.

Lagoya's performing magnetism carries over to the flip side with two of the most popular pieces in the guitar repertoire: Albeniz's Asturias (Leyenda) and Tarrega's Recuerdos de la Alhambra.

The pedal drone and flamenco elements of Asturias are well mixed with La goya's coloristic gift, while his noble tremolo is exploited for deep emotional impact in Recuerdos. The side ends with spirited accounts of Villa-Lobos' Etude No. 11 and Torroba's Nocturno.

[See also Claude Bolling's Concerto for Classic Guitar and Jazz Piano, re viewed on page 112, in which Lagoya is a soloist.]

----70 Angel Romero

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON keeps two fine guitarists before the public: Narciso Yepes and Siegfried Behrend. Nei ther is a particularly charismatic per former, but what they lack in showmanship they make up for with their sympathetic interest in adventurous repertoire. Behrend's "Chitarra Italiana" album (DG 2530 561) spans four centuries, from anonymous early lute music to music of the avant-garde com poser Sylvano Bussotti (b. 1931). Behrend favors a clean, slightly metallic guitar tone, and his lute imitations are often uncanny. He also plays music by Mauro Giuliani (the ubiquitous Op. 61) and by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco, composers whose extensive association with the guitar has led many people to think of them as Spanish rather than Italian.

I heard the Behrends (speaker Claudia Brodzinska on the DG disc is the guitarist's wife) perform Bussotti's pop song ultima rara? (sic) at the Goe the Institute in San Francisco several years ago; it was one of the most pro vocative experiences I have ever had at a guitar recital. The work's dynamic and melodic gestures are fragmentary and self-contained. There is no gradual rise to a climax; the piece could stop anywhere (in fact, Behrend's earlier re cording of it-now deleted-is three minutes longer than this 1974 version).

Mme. Behrend shrieks, gulps, sobs, yelps, sighs, groans, yawns, laughs, cackles, and moans the vocal part. The previous recording, with Bussotti him self as speaker, may be slightly prefer able because the guitar is more for ward, but this performance is quite sufficiently hair-raising.

Narciso Yepes' two latest Deutsche Grammophon albums unearth four contemporary Spanish concertos, all of which he plays on a ten-string guitar of his own invention. With Rafael Fruhbeck de Burgos and the London Symphony, Yepes performs Mauricio Ohana's Tres Graficos and Antonio Ruiz-Pipo's Tablas (2530 585),' and Odon Alonso and the Orquesta Sinfonica of Spanish Radio TV accompany him in concertos by Salvador Bacarisse and Ernesto Halffter (2530 326).

The guitar parts in the Ohana and Ruiz Pipo works owe their improvisatory character to the cante jondo of Andalusian flamenco. Bacarisse's concerto is conservative in a melodic, classical idiom; Halifter's work stresses polyphony and rhythmic variety. Yepes' playing of all four works is introspective and artistically immaculate.

THE immense popularity of Julian Bream, whose platform manner is to me the most beguiling of all of today's concert artists, has not closed his inquiring mind to further explorations.

His musical sympathies stretch from Dowland through transcriptions of piano pieces by Debussy to contemporary composers. It was for Bream that Benjamin Britten wrote the Nocturnal, a fiendishly difficult guitar solo which has become a modern classic. Bream's latest adventure is a concerto by his compatriot Lennox Berkeley (RCA ARL1-1181). It is a quiet, sophisticated work in three movements scored for winds, horns, and strings. Its essentially English character is defined by characteristic harmonic subtleties and pastoral nuances, and few guitarists could surpass Bream's eloquent refinement in the solo part. It's a pity, however, that RCA didn't think it appropriate to put something more unusual on the other side than Rodrigo's overworked Con cierto de Aranjuez. Bream's previous solo album (RCA ARL1-0711) introduced Giuliani's Le Rossiniane, variations based on opera themes on which the guitarist did a bit of surgery to pro duce two wildly virtuosic vehicles. The second side is given over to Sor's gracious Grand Sonata, Op. 25, played (for a welcome change) in its entirety.

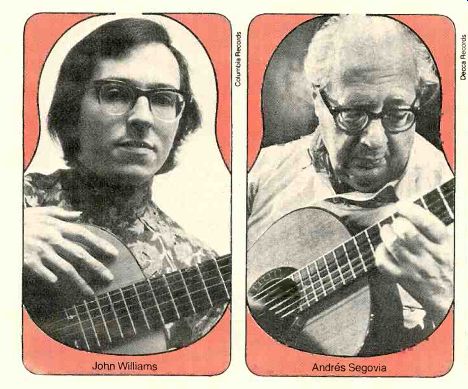

John Williams, whose duet albums with Bream (RCA LSC-3257 and ARL1-0456) turn the friendly rivalry of fingerboard champions into jousts of John Williams wit, is a thirty-five-year-old Australian who teaches at London's Royal College of Music. Williams is a technical wizard in every aspect of guitar playing, but, as his notes to "Virtuoso Mu sic for Guitar" ( Columbia MS 6696) point out, virtuosity does not necessarily mean "fast and loud." He proves it with his tenderly expressive handling of the limpid melodies of Paganini's Sonata in A, which he arranged for solo guitar from its original guitar and violin scoring. And in the vivacious Partita by Stephen Dodgson, Williams' all-but electric energy quickens the music's perpetual motion.

On "More Virtuoso Music for Guitar" ( Columbia MS 6939), Williams again demonstrates that tenderness is one of his strong suits in the lovely Paduana by Esaias Reusner (1636-1679).

Bach's Prelude, Fugue and Allegro is kept moving with no perceptible breaks by Williams' fluent left hand; works by Mudarra and Praetorius are delineated with a pungent, lute-like tone; and Villa-Lobos' Prelude No. 4, one of the most familiar pieces in the guitar repertoire, is presented with all its delicate harmonics intact.

Williams opens "Virtuoso Variations" ( Columbia MS 7195) with a transcription (by Williams) of the Chaconne from Bach's Violin Partita No. 2. Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (and Andres Segovia perhaps others as well) has called the Chaconne "the single greatest piece of music ever written." The twenty-nine variations of this monumental work give Williams no apparent difficulties.

His playing goes well beyond mere technical considerations, plumbing structural depths and rising to emotion al heights. For the rest of the program, two Dowland galliards and Sor's "Mozart" Variations are joined by Giuliani's captivating Variations on a Theme by Handel, actually the famous Harmonious Blacksmith from the Harpsichord Suite in E. Williams plays the theme and its five variations with an engaging directness that keeps Giuliani's decorative complications nice ly in their place, never obscuring the main musical subject. [Williams' latest guitar record, a group of Scarlatti sonatas and Villa-Lobos preludes, is reviewed by Eric Salzman in the Classical section.

GUITAR lovers are fortunate that surveys of contemporary guitar recordings must continue to include the latest by Andres Segovia, the father of the twentieth-century guitar renaissance. Like Pablo Casals, whom he resembles physically as well as spiritually, Segovia is a romantic. His guitar tone is warm and opulent, his bel canto phrasing sings with the heart's simplicity.

Among the more interesting contemporary Spanish and Latin American works on Segovia's freshly recorded "Intimate Guitar," Volume I (RCA ARL1-0864) and Volume II (RCA ARL1-1323), are a set of variations by Jose Munoz Molleda, a Basque folk song by Padre J. S. San Sebastian, Dipso by Vicente Asencio, and Manuel M. Ponce's Prelude in E. Certain of Segovia's performance practices (especially in Bach) and fingering techniques have been updated by younger guitarists, but the old master's playing has retained much of its imperious character well into his eightieth year, and he is still the source to which his artistic descendants repair for inspiration.

------------------

DO IT YOURSELF

THE best way to get a feeling for the difficulties and subtleties of the classical guitar is to learn to play it yourself. Frederick Noad, guitarist and scholar, has edited three beautifully re searched volumes of guitar music, The Renaissance Guitar, The Baroque Guitar, and The Classical Guitar (available in music stores or by mail from Music Sales Corp., 33 West 60th Street, New York, N.Y. 10023, $6.95 each). They contain many of the pieces in the al bums included in this roundup of re cent guitar recordings. Even if you don't play, it is instructive to read along as Romero, Williams, or Behrend negotiates the virtuoso passages in Giuliani's Op. 61 or Variations on a Theme of Handel, Dowland's Queen Elizabeth's Gaillard, Mudarra's Fan tasia, Narvaez's Guardame las Vacas, or Roncalli's Gavotte and Gigue from the Capricci Arrnonici. As pure pleasure imperceptibly merges with the learning experience, there comes, imperceptibly, a deeper understanding of this exquisite musical art.

-S. v.B.

-------------------

Also see:

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR (Feb 1977)

AUDIO BASICS: The Greater Good

SMALL LABELS: They have a lot to offer collectors of folk, jazz, and blues, IRA MAYER

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)