Equipment Test Reports

By Hirsch-Houck Laboratories

Garrard GT55 Automatic Turntable

THE Model GT55 replaces the well established Zero 100 and its successors at the top of the Garrard automatic turntable line. It has the articulated "zero-tracking-error" tone arm originally developed for the Zero 100, but it is now constructed of magnesium alloy to reduce the arm mass to 14 grams (which Garrard claims is the lowest mass of any pivoted tone arm sold as part of an integrated record player).

The anti-skating compensation is applied, as before, by magnetic repulsion, using tapered magnets that reduce the anti-skating force as the arm moves inward (since its head offset angle decreases simultaneously, less skating force is created at smaller playing diameters). The ball-bearing arm pivots are said to have 30 milligrams of friction in the horizontal plane and 20 milligrams vertically, measured at the stylus.

An unusual feature of the Garrard GT55 tone arm is the location of its rear portion (consisting of the vertical pivot and the adjustable counterweight) below the axis of the forward portion of the arm. It is so placed to reduce warp wow, which is aggravated in many tone arms by the location of the vertical pivots too high above the disc-surface plane.

The tracking force is adjusted by rotating the counterweight after-the arm has been balanced with a cartridge installed. The scale on the counterweight is calibrated from 0 to 3 grams at intervals of 0.25 gram. The anti-skating dial, which has separate scales for elliptical and CD-4 styli, is located next to the base of the arm.

The 4-pound cast nonferrous platter is belt-driven by a d.c. servo-controlled motor operating at 1,000 rpm. The motor speed is electronically controlled and regulated, and the illuminated stroboscope markings under the platter can be viewed through a window on the motorboard while a record is being played. The rubber record mat has concentric rings of raised rubber "dots" that provide good support while contacting a minimum area of the recorded portion of a disc.

The Garrard GT55 can be used as a multiple-play unit (record changer) by inserting the long spindle provided into the center hole and loading a stack of up to six records of the same size and speed onto it. The edge of the record stack is supported by a post just out side the diameter of the turntable. For single-play operation a short center spindle (it rotates with the records) is used.

The basic operating controls are located at the right front of the motorboard. They consist of four levers. One of these sets the arm indexing diameter for 7-, 10-, or 12-inch records. For automatic operation, and whether a single disc or a stack is loaded on the spindle, the MODE lever is moved to the AUTO position. In this position the arm indexes to the selected diameter, play begins, and the unit shuts off after the last record has been played.

Pushing this lever past AUTO to REPEAT causes any record on the turntable to be repeated indefinitely until the lever is released manually. For single-play operation the MODE lever can be set to MAN (manual), which starts the motor. in any mode of operation a separate AUTO lever starts the playing cycle (in MAN the arm can be cued manually, of course).

The fourth lever is the CUE control, which raises the arm when moved to the rear and lowers it when moved to the front. The arm motion is well damped in both directions, and a small knob under the arm adjusts the rate of descent. At the left front of the motorboard is the speed selector (for 33 1/3 or 45 rpm) and a vernier adjustment with a nominal range of ±3 percent. Both controls operate electronically through the motor servo system.

The key specifications of the Garrard GT55 include a-66-dB (DIN "B") rumble level, 0.05 percent wow and flutter, and a minimum tracking force of 0.75 gram. An optional mounting base and plastic dust cover are available, as well as a combination deluxe base and cover (BDC-8). Price: GT55, $249.95; standard base, $15.95; dust cover, $9.95; deluxe combination, $39.95.

Laboratory Measurements. We tested the Garrard GT55 with a Pickering XSV/3000 cartridge installed in its arm. (At first we attempt ed to use a heavier-than-average cartridge [9 grams] but found that the counterweight could not be moved back far enough to balance it. The counterweight will balance any cartridge weighing up to 6 grams, however, which should be adequate for the majority of cartridges.) The calibration of the tracking-force scale was accurate to within 0.05 gram, and the force on the top record of a stack of six was only 0.lgram lower than on the first.

For all practical purposes, the "zero-tracking-error" arm lived up to its name. At a 6 inch radius (actually slightly larger than the maximum playing radius of a 12-inch record) we measured an error of about 1 degree, or 0.16 degree per inch. This minuscule error was the largest we found over the record surface. Elsewhere, down to a 2-inch radius, the error was zero, or at least below our ability to detect and measure it.

The arm resonance with the XSV/3000 cartridge fell between 6 and 7 Hz, with an amplitude of 1 I to 12 dB. The Pickering cartridge is probably more compliant than most, and it has a slightly higher mass due to its integral record brush as well, all of which makes it difficult to assess the contribution of Garrard's arm-mass reduction to the subsonic response of the player system. The arm and signal-cable capacitance to ground was 135 picofarads per channel and 63 picofarads between the "hot" leads of the two channels. The latter could adversely affect the measured (but not the audible) channel separation at the highest audio frequencies with some cartridges. However, the measured capacitance of the GT55 appears to be typical of most record slayers.

The turntable speed could be varied over a ±3 percent range at 33 1/3 rpm and from +5.7 to -4 percent at 45 rpm. It did not change with line-voltage variations. The flutter (wrms) was 0.09 percent and occurred principally in the region of 6 Hz. Unweighted rumble was-34 dB, improving to-58 dB with ARLL weighting (note that the DIN "B" weighting curve used by Garrard to derive their ratings will usually give a "better" figure than an ARLL weighted measurement). Surprisingly, in view of the motor's relatively high speed of 1,000 rpm, the rumble was principally in the vicinity of 5 Hz (perhaps be cause of the proximity to the tone-arm's resonance frequency).

The operation of the Garrard GT55 was smooth and silent. The starting cycle, for a single record or the first of a stack, required about 14 seconds; the change cycle in multiple-play operation took about 12 seconds, which is an average figure for record changers. The cueing system, like that of the original Zero 100, was totally free of lateral drift, and ranks in our view as one of the most pre cise available. The variable cueing descent-rate adjustment, although there is nothing in its markings to suggest that more than a single turn (or less) is required to cover its full range, turns through 5 1/2 complete revolutions (the manual makes this clear). Minimum cueing time was about 4 seconds.

The isolation against externally conducted vibration through the deluxe BDC-8 base and cover combination was about average for automatic turntables. However, entirely re moving the plastic dust cover reduced the GT55's susceptibility to vibration-induced feedback appreciably.

Comment. We noted some areas of subjective reaction to the GT55 worth mentioning. In contrast to the wide flat levers of its predecessors, the slender, rod-like control levers seemed less convenient to operate, and care was necessary-as it is with a number of competitive players-to avoid jarring the unit when operating some of the controls. Also, the styling of the unit did not, to our eyes, properly convey the image of the top-quality player the GT-55 is. However, everything worked perfectly, and with impressive silence and smoothness. Even the anti-skating calibration (which on many players bears little re semblance to the actual compensation required for equally effective tracking of both stereo channels) was accurate by our tests, as we had found it to be some years ago on the Zero 100. Rumble and flutter of the GT55 were consistent with what we would expect from a top-of-the-line automatic record player. In other words, the turntable does just what Garrard claims it will, and it does it very well.

Advent Model 300 Stereo FM Receiver

IN the face of a trend toward stereo receivers I whose power ratings, size, and weight rival those of many "super power" amplifiers and whose control panels combine the features of a recording console and the flight engineer's desk on a 747, Advent Corporation has chosen to develop a very basic, high-quality receiver-literally a "no frills" product. The Advent Model 300 is a low-power stereo FM receiver rated to deliver 15 watts per channel to 8-ohm loads with both channels driven, from 40 to 20,000 Hz, with less than 0.5 percent total harmonic distortion.

The 300 is easily the most compact stereo receiver we have seen. In its black semi-gloss metal cabinet, it is approximately 16 inches wide, 9 inches deep, and 31/2 inches high, and it weighs a mere 11 pounds. The tuning dial is a round, silver-finish plate with a concentric black knob that operates a smooth vernier reduction mechanism (similar to the dial used on Advent's Model 400 monophonic FM radio). The dial is framed in a white rectangle together with a red LED STEREO light and two closely spaced LED's that serve as a tuning indicator. As the receiver is tuned through a station, one light comes on brightly and dims as the other begins to glow. When the two are of equal brightness, the receiver is tuned to the exact center of the channel. There is a fourth LED pilot light next to the power slide switch.

Across the lower portion of the front panel are the input selector knob (Aux, TUNER, and PHONO) and the volume-control knob, followed by three smaller knobs for channel BALANCE and the BASS and TREBLE tone-control functions. The knobs are black with white index lines that make their settings clearly visible even at a distance.

Above the knobs are slide switches for the TAPE MONITOR, LOUDNESS, MONO/STEREO, and FM MUTING functions. Two switches separately activate the two pairs of speaker out puts, and there is a headphone jack on the panel. In the rear of the receiver are jacks for the various inputs and outputs, plus two pairs of jacks, normally joined by removable juniper links, that carry the preamplifier outputs and power-amplifier inputs. Insulated binding posts are used for the speaker outputs and the 300-ohm antenna inputs. A covered phono jack supplies +18 volts to power an accessory such as the Advent MPR-1 microphone preamplifier. Circuit protection is supplied by an a.c. circuit breaker whose red reset button protrudes from the rear of the receiver.

Advent's philosophy holds that a high-quality FM tuner and phono preamplifier need not cost more than a run-of-the-mill design. The major reason for the high cost of many receivers is the heavy-duty power supply and output transistors that go with their admittedly impressive power capabilities. The Advent's actual sensitivity (ability to receive weak stations without excessive noise and distortion) is as high as will ever be needed by the majority of users. The phono preamplifier was de signed to be immune to interaction with phono-cartridge inductance, which affects the high-frequency response of many preamplifiers, and to have an effectively negligible noise level (inaudible under conditions of practical use). In addition, the frequency response out side the audio range-particularly below 20 Hz, where turntable rumble and record warps can produce subsonic overload and muddy the sound-has been sharply attenuated. Ad vent's high-pass filter, which affects the response by less than 1 dB at frequencies of 20 Hz and above, cuts the output at 4 Hz (the area where warp effects are at their worst) by more than 30 dB.

As for the power output of the Model 300, Advent points out that it can deliver an adequate sound level with speakers of normal efficiency (such as their own) in typical home environments without a sense of strain or audible distortion. The preamplifier output and main amplifier input connections make it a simple matter to use an external power amplifier, retaining the virtues of the receiver's tuner and phono preamplifier. In a four-channel installation, the 300's own amplifier will usually be more than sufficient for the back channels.

The Advent Model 300 is also available as the Model 300/12 for operation from a 12-volt battery in cars, boats, trailers, and the like.

An a.c.-operated Model 300 can be converted by Advent for 12-volt operation, though it will then no longer be usable on a.c. without a 5-amp d.c. adapter. Full power and performance of the receiver are available when operating from a 12-volt source. Price: $259.95.

Laboratory Measurements. After one hour of preconditioning at one-third power output, the cabinet of the receiver was about as warm as it becomes in normal operation. The 1,000-Hz output at the clipping point was 18 watts into 8 ohms, 18.5 watts into 4 ohms, and 11.7 watts into 16 ohms.

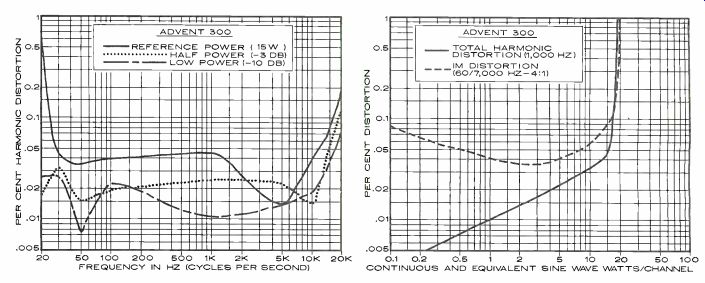

The 1,000-Hz total harmonic distortion (THD) with both channels driven into 8-ohm loads was under our measurement limit of 0.003 percent up to 1 watt output and rose to

--------- FREQUENCY IN HZ (CYCLES PER SECOND CONTINUOUS AND EQUIVALENT SINE WAVE WATTS/CHANNEL

... 0.045 percent at the rated 15 watts. The inter-modulation distortion (IM) was less than 0.05 percent from 0.5 to 8 watts output, rising to 0.09 percent at 15 watts. It also rose some what at lower power levels, reaching 0.085 percent at 0.1 watt (this reflects the residual noise contributed by the tone-control section, since the power amplifier alone has substantially lower IM at very small outputs).

At the rated power output, the THD was between 0.04 and 0.05 percent from below 30 to above 1,000 Hz, falling to 0.015 percent at 5,000 Hz and rising to 0.18 percent at 20,000 Hz. Although Advent's full-power ratings for the Model 300 do not extend below 40 Hz, we measured its distortion at 0.67 percent at 20 Hz. At half power and lower levels, the THD was lower still, typically between 0.01 and 0.03 percent from 20 to 1,000 Hz and about 0.1 percent at 20,000 Hz.

The RIAA phono equalization was as flat as our measuring equipment (±0.25 dB) from 50 to 15,000 Hz, and very nearly as good over an extended measurement range of 20 to 20,000 Hz (the low-frequency filter caused a slight rise of about 1 dB at 25 Hz). Measured through the inductance of typical phono cartridges, the phono response changed by no more than 0.5 dB up to 20,000 Hz.

The tone controls had conventional characteristics, with the bass-turnover frequency shifting between approximately 200 and 800 Hz as the control was varied and the treble response hinging at about 2,500 Hz. The maximum control range of about ±10 dB is more than adequate and helps avoid the risk of exceeding the amplifier's power capabilities.

The loudness contours showed a moderate low-frequency boost and a smaller high-frequency boost as the volume-control setting was reduced.

To drive the Model 300 to a reference out put of 10 watts, a 0.07-volt signal was required at the Aux input and 1.5 millivolts at the PHONO input. The respective unweighted S/N figures were 72 and 70 dB. The phono preamplifier overloaded at 110 millivolts, a perfectly safe level for any magnetic cartridge of reasonably good quality.

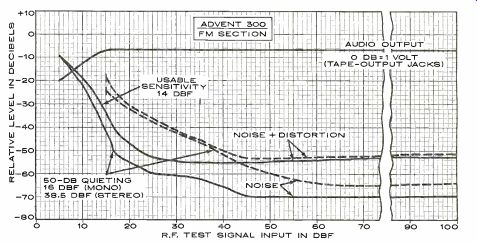

The FM tuner had an IHF sensitivity of 14 dBf (2.7 microvolts, or 1uV) in mono. In stereo, the IHF sensitivity was 19 dBf (5 uV).

More important than this figure is the 50-dB quieting sensitivity, which was 16 dBf (3.5 uV) in mono with 0.9 percent THD, and 38.5 dBf (46.3 µV) in stereo with 0.5 percent THD. The ultimate quieting, at 65 dBf (1,000 uV) input, was 70 dB in mono and 65 dB in stereo, with respective distortion levels of 0.21 and 0.24 percent. The stereo distortion with out-of-phase (L-R) modulation of the two channels was 0.45 percent at 100 Hz, 0.21 percent at 1,000 Hz, and 0.2 percent at 6,000 Hz.

The FM frequency response was flat within ±0.6 dB from 30 to 15,000 Hz. The stereo channel separation was more than 50 dB at 1,000 Hz, 30 and 27 dB at 30 and 10,000 Hz, and still a very good 24 dB at 15,000 Hz. The low-pass filter in the tuner output reduced the 19-kHz pilot carrier leakage in the audio out put to a good-67 dB without impairing the high-frequency response of the FM section.

The capture ratio of the tuner at 45 dBf (100 uV) was 1.5 dB with 60 dB of AM rejection.

At a higher input of 65 dBf, the capture ratio was nearly the same (1.6 dB), and the AM rejection improved to an excellent 70 dB. The image rejection at 98 MHz was 60 dB, and the alternate-channel selectivity was also excellent at 83 dB. Adjacent-channel selectivity, always much less than the alternate-channel measurement, was 5.5 dB. The muting thresh old was set at 24 dBf (9 uV) and the automatic stereo threshold was at 15 dBf (3 uV). The twin-LED tuning indicator was very accurate, providing minimum distortion when the two intensities matched. However, this called for some critical judgment by the user, as com pared with the relatively simple task of centering a meter pointer.

--------- ADVENT 300 FM SECTION

Comment. Probably one of the factors contributing to our enthusiasm for the Advent Model 300 was its nearly flawless execution of the "no-frills" concept. We have always ad mired value engineering of the sort associated with products from Advent and a few other companies, in which a maximum of consumer-benefiting performance and features are provided for a minimum cost. It is relatively easy to make a "super" product if price is no obstacle, but it requires some ingenuity to achieve a high level of performance at a relatively low cost. This is exactly what Advent has done in the Model 300.

An economical approach to product design does have its negative aspects, too. For example, the tuning-dial scale, though quite accurate, is cramped over much of its range and widely spread out at the high-frequency end.

Many times we had to guess which station was tuned in since 1 megahertz occupies about 1/8 inch at most points on the dial scale.

The LED tuning indicator, as we have stat ed, was very accurate. As a matter of fact, it was more precise in its function than most of the meters we have seen on tuners and receivers, as well as being much smaller and probably less expensive. On the other hand, it re quires more care than we suspect many users will give it in order to realize the full tuning accuracy of the receiver. Fortunately, a moderate amount of mistuning is not noticeable in use, and we assume that if anyone hears distortion or noise because of mistuning, he will correct it on the spot. We also noted a slight warm-up drift, lasting a few minutes, in our sample. Although this drift was sufficient to extinguish one of the tuning lights, it was of questionable significance because it could not be heard as an increase of noise or distortion.

In any case, if the tuning is set correctly after about 5 minutes of operation, it will remain as set indefinitely.

The Model 300 lacks such refinements as time delays in the turn-on and turn-off cycles to prevent speaker thumps. Of course, with a powerful amplifier these are vital for the preservation of one's speakers. With the Model 300, the "thump" is audible but hardly disturbing, let alone dangerous. The FM muting is good, with enough time lag to permit a quick scan across the band in total silence.

There is only a trace of a noise burst when tuning slowly through a signal, as would normally be done.

All of which brings us to the question of how a 15-watt receiver sounds in this day of 100- to 200-watt amplifiers and receivers. In a word, great! Critical A-B tests in FM reception between the Advent Model 300 and a receiver with more than ten times its power and three times its price revealed absolutely no audible difference between the two at any listening level within the sound output-level capability of the Model 300 (of course, the other receiver could play much louder). Even that limit is surprisingly loud, despite our use of fairly inefficient acoustic-suspension speakers. Obviously, this is not a receiver one would choose to play music at rock-concert-hall levels, but at somewhat lower volumes it does as good a job as anything we have heard.

The phono preamplifier sounded first-rate, and as a demonstration of its low noise level, at maximum gain only a faint hiss could be heard within a foot or so of the speakers.

We find it refreshing that this caliber of sound, combined with reasonable control flexibility, has been designed into a really small, light package, one whose installation does not call for the services of an Olympic weight lifter or specially reinforced furniture.

Although one can buy less expensive receivers, some of which may have a few more watts or a couple of extra features, it is a safe bet that they will be two or three times the size (and weight) of the Advent Model 300, far more formidable for the uninitiated to operate, and will sound no better-probably not as good.

+++++++++++++++++

Pickering XSV/3000 Phono Cartridge

DURING the development of the fine XUV-4500Q stereo/CD-4 cartridge, Pickering evolved several new techniques, including a high-efficiency magnetic system and a new stylus shape, that were instrumental in enabling them to achieve their design goals.

As often happens with technological advances, they are initially costly, but in time they can be adapted to lower-cost products with an overall uplifting of performance standards.

This was the background for the creation of the new XSV/3000, which heads the rather comprehensive line of stereo cartridges bearing the Pickering name. The internal magnetic structure of the XSV/3000 is quite similar to that of the XUV-4500Q, and externally the two are identical. Much of the credit for the performance of the XUV-4500Q went to its "Quadrahedral" stylus ( Pickering's proprietary equivalent to the Shibata-shape stylus, which is able to trace very high frequencies while distributing the vertical tracking force over a wide area of the groove wall to minimize record wear). This stylus was also responsible for much of the high cost of the XUV-4500Q.

The XSV/3000 was intended to bring the same order of performance to the playing of stereo (and matrixed quadraphonic) discs at a considerably lower price. To that end, the, contours of the Quadrahedral stylus were modified and made less extreme since operation above 20,000 Hz was not required. In the process, the general contour of the stylus' contact with the groove wall was maintained to preserve some of the benefits of a long con tact stylus. The new stylus is called the "Stereohedron" in recognition of its kinship to the Quadrahedral.

The Pickering XSV/3000 is designed to track at forces between 0.75 and 1.5 grams and to have a nominal output of 5 millivolts at a velocity of 5.5 centimeters per second (an/ sec). The replaceable stylus, like those of other Pickering cartridges, has a hinged "Dustamatic" brush that rides on the record to pick up surface dust. Accessory styli are available for playing mono LP and 78-rpm records, Price: $99.95.

Laboratory Measurements. In a typical tone arm of good quality, the Pickering XSV/3000 tracked our high-level test records easily at its minimum rated force of 0.75 gram, including the maximum level (100 microns) of the German Hi Fi Institute test record. In fact, the 30-cm/sec, 1,000-Hz tones of the Fairchild 101 record were reproduced as a clean sine wave (a very unusual occurrence in itself) at only 0.5 gram! We used 0.75 gram during our other tests.

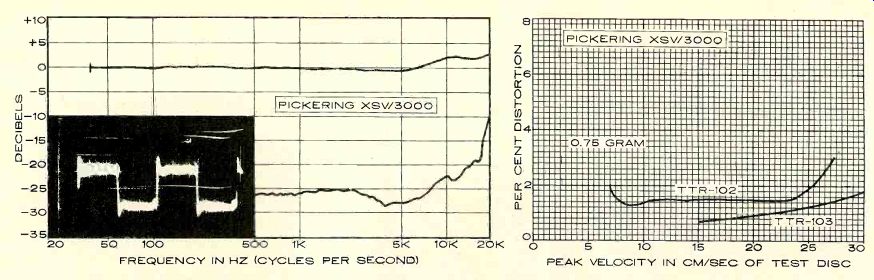

With a cartridge load of 47,000 ohms in parallel with 200 picofarads (the nominal rated load capacitance is 275 picofarads), the frequency response rose slightly starting at 7,000 Hz to a maximum of about +3 dB at 20,000 Hz. Overall, it was well within ±2 dB from 40 to 20,000 Hz, the full range of the CBS STR 100 test record. The channel separation measured 20 to 30 dB up to about 15,000 Hz and remained an excellent 10 to 15 dB at 20,000 Hz. The response changed by less than 1 dB at any frequency when we increased the capacitive load from 200 to 435 picofarads.

The cartridge output, which was identical on both channels, measured 3.45 millivolts at a velocity of 3.54 cm/sec. The 1,000-Hz square-wave response showed a single 50 percent overshoot with ringing at a very low level. The low-frequency resonance in the test tone arm was at 5 Hz, a rather low figure.

Since we have no reason to believe that the tone-arm mass was unusually high, it is clear that the stylus compliance of the XSV/3000 is very high and that it should be used in a very low-mass arm if at all possible (although we experienced no tracking difficulties, even with moderately warped records).

The intermodulation distortion, using the TTR-102 test record, was a constant 1.5 percent up to about 24 cm/sec, and the maximum velocity of 27 cm/sec was tracked with only 3 percent IM distortion. The repetition-rate distortion using the 10.8-kHz tone bursts of the TTR-103 test record was typical of many fine cartridges, increasing from 0.7 to 1.8 percent as the velocity increased from 15 to 30 cm/sec.

In a subjective tracking test using the TTR-110 "Audio Obstacle Course-Era III record, the XSV/3000 showed a slight "sand paper" quality at the highest level of the sibilance test, but otherwise it did a perfect job of tracking these very high-level passages.

Comment. Judged by its measured performance, the Pickering XSV/3000 clearly be longs at or near the top of the most select group of contemporary phono cartridges. It will track higher velocities at lower forces than any other cartridge we have tested.

In the final analysis, the appraisal of a cartridge must come down to a matter of sound quality. To our ears, the XSV/3000 is one of the "sweetest," smoothest-sounding cartridges we have had the pleasure of using. If ever a cartridge merited the adjective "un strained," this one does. After our tests revealed its extraordinary high-level tracking ability, we also listened closely for signs of distress when playing difficult records. We heard none. Unless there are some subtle characteristics of the XSV/3000 that you don't care for, or some in another cartridge that you prefer (tastes differ), we don't see how you can do better at any price.

-------------- In the graph at left, the upper curve represents the

smoothed, averaged frequency response of the cartridge's right and left channels;

the distance (calibrated in decibels) between it and the lower curve represents

the separation between the two channels. The inset oscilloscope photo shows

the cartridge's response to a recorded 1,000-Hz square wave, which gives

an indication of resonances and overall frequency response. At right is the

cartridge’s response to the intermodulation-distortion (IM) and 10.8-kHz

tone-burst test bands of the TTR-102 and TTR-103 test records. These high

velocities provide a severe test of a phono cartridge's performance. The

intermodulation-distortion (IM) readings for any given cartridge can vary

widely, depending on the particular IM test record used. The actual distortion

figure measured is not as important as the maximum velocity the cartridge

is able to track before a sudden and radical increase in distortion takes

place. There are very few commercial phonograph discs that embody musical

audio signals with recorded velocities much higher than about 15 cm/sec.

----------------------------

++++++++++++++++++++

Yamaha NS-5 Speaker System

THE larger Yamaha speaker systems em ploy advanced technology, such as beryllium domes, to achieve their high performance goals. Unfortunately, their prices are correspondingly high. In the new NS-5 speaker, Yamaha has attempted to capture the essential qualities of their finest speakers in a unit with a much lower price.

The NS-5, which is manufactured in the United States to Yamaha's specifications, is a compact, two-way acoustic-suspension system whose dimensions of 203/4 inches x 113/4 inches x 11 3/4 inches deep and net weight of 25 pounds make it a true bookshelf speaker. It has a 10-inch, long-throw woofer with a 1.5-inch diameter, a four-layer voice coil, a neoprene edge surround, and a 12-ounce ceramic magnet. There is a crossover at 1,500 Hz to a 1-inch tweeter with resin-impregnated soft cloth dome. The crossover network attenuates the tweeter response at a 12-dB-per-octave rate and the woofer response at a 6-dB-per-octave rate.

One of the major goals in the design of the NS-5 was high efficiency, so that the speaker could be used satisfactorily with amplifiers rated as low as 10 watts per channel. Its nominal maximum power is 50 watts, but, as Yamaha points out, it can be used with more powerful amplifiers if care is taken to avoid exposing the speaker to high-level transients.

The enclosure, including the speaker board, is finished in walnut-grain vinyl. A black cloth grille normally covers the entire front of the speaker, but it can easily be removed if the room decor is more compatible with a walnut-grain finish. Four flush-mounted plastic receptacles grasp the mating projections on the grille frame and present a finished appearance when the grille is removed.

Both the woofer and tweeter of the NS-5 are mounted flush with the front surface of the cabinet to minimize edge diffraction effects. The level balance between the drivers is set at the factory, and there are no external adjustments. The binding-post terminals are recessed into the rear of the cabinet. Price: $100.

Laboratory Measurements. The reverberant-field frequency response of the Yamaha NS-5 was notably smooth and free of contour irregularities. The close-miked bass response, almost perfectly flat from 200 to 700 Hz, rose at lower frequencies to a maximum of +5 dB at 50 Hz and fell at a 12-dB-per-octave rate below that frequency. Joining the two curves, we obtained an overall frequency-response curve varying only ±3 dB from 32 to 15,000 Hz (most of the variation was in the low bass; the response was within ±2 dB from 75 to 15,000 Hz).

Yamaha has a distortion specification of 1 percent or less at all frequencies above 100 Hz with a 3-watt input. Our distortion tests normally cover the range from 100 Hz down, but the distortion at 100 Hz was only 0.6 percent at 10 watts and 0.22 percent at I watt, tending to confirm Yamaha's rating. At a 1-watt drive level, the distortion reached 1 percent at 60 Hz, rising to 8 percent at 30 Hz. At 10 watts input (based on the nominal 8-ohm system impedance) the distortion reached 6 percent at 50 Hz and 13.5 percent at 40 Hz.

When we drove the speaker to produce a constant sound-pressure level (SPL) of 90 dB at a distance of I meter, the distortion level was between the 1- and 10-watt curves down to 50 Hz, but it rose somewhat more steeply at lower frequencies.

The efficiency of the Yamaha NS-5 was, as claimed, quite high for an acoustic-suspension system. Driving the system with 1 watt of random noise in the octave centered at 1,000 Hz, the SPL at a distance of 1 meter was 92 dB. This is about 3 to 4 dB higher than the output of most acoustic-suspension systems.

The impedance of the NS-5 reached its mini mum of 5 ohms at 100 and 5,000 Hz and its maximum of 18 ohms at 56 Hz. Over most of the audio range, the impedance was between 5 and 9 ohms.

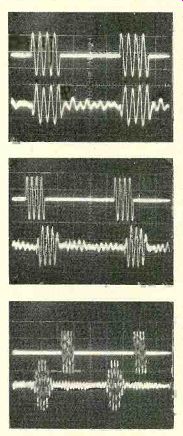

The tone-burst response was good at all frequencies. Yamaha claims that the characteristics of the drivers and crossover network have been carefully matched to eliminate any response anomalies in the crossover region.

There was nothing in our frequency-response measurements to suggest any deleterious effects of a crossover at any frequency, so we carefully explored the 1,000- to 2,000-Hz band with the tone-burst signals (which can often show up any phase or amplitude mis match between the drivers). We found no evidence of such effects; the 1,500-Hz tone burst photo is typical of the response in that band. Dispersion-as implied by our other test results-was fine.

Comment. Insofar as our measurements can predict sound quality, we would expect the Yamaha NS-5 to have a very neutral, un colored sound. It came as no great surprise, therefore, to find that this would be an accurate description. From the first, we could hear that it was "all there," without any significant emphasis or lack in any part of the spectrum.

This was further confirmed in the simulated "live-vs.-recorded" listening test, in which the NS-5 was able to imitate the live source with high accuracy, especially in the middle and high-frequency ranges. The test does not operate reliably at low frequencies, and we often hear slight colorations in the lower middles that we suspect can be attributed to interactions between the speaker and the room.

This is essentially what we found with the NS-5: a trace of warmth in the lower middles, but elsewhere a highly accurate rendition of the "original" sound in an A-B comparison.

It seemed to us that the NS-5 should easily hold its own in a comparison with any of the several very fine speakers in its price range.

Since we did not have any of them on hand, we limited our direct speaker comparisons to several much more expensive units priced be tween $150 and $450. Except possibly in the low bass (and it is by no means lacking in that range, either), the NS-5 generally sounded as good to us as most of the others, and in some respects it seemed to outperform a couple of them. Since we had several speaker systems stacked on top of each other, we noted with interest that it was usually impossible to tell which one of the several fine systems was playing without standing very close to the group. When differences are that slight, we do not consider them to be very significant.

-------- Photos taken at (left to right) 100, 1,500, and 10,000 Hz

typify the good tone-burst response of the NS-5 system.

The high efficiency of the NS-5 was evident from the beginning. We drove it from a 15-watt receiver without difficulty, as well as from a 160-watt-per-channel receiver. Al though the latter might seem like a risky pairing, we found that the NS-5 delivered such a high volume of undistorted sound with little power input that one would be most unlikely to overdrive it unwittingly in normal listening (watch out for those transients, though!).

Our conclusion is that Yamaha has hit its design target squarely. The NS-5 is a practical, handsomely finished, moderately priced speaker whose sound quality completely be lies its modest proportions and price tag.

Also see:

FIEDLER OF BOSTON: A profile of the builder of America's musical bridges, IRVING KOLODIN

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)