CLASSICAL DISCS and TAPES: A Little

X-mas Music, WILLIAM KIMMEL, Gustav Leonhardt's Brandenburgs, STODDARD LINCOLN,

Jean -Baptiste Lully's Alceste, ERIC SALZMAN, Kreisleriana, GEORGE JELLINEK,

Giuseppe Verdi's II Trovatore, GEORGE JELLINEK

Reviewed by RICHARD FREED, DAVID HALL, GEORGE JET LINEK, PAUL KRESH, STODDARD LINCOLN, ERIC SALZMAN

J. S. BACH: Sonata in B Minor for Flute and Harpsichord (BWV 1030); Sonata in A Major for Flute and Harpsichord (BWV 1032); Trio Sonata in G Major for Flute, Violin, and Continuo (BWV 1038); Sonata in E Minor for Flute and Continuo (BWV 1034); Sonata in E Major for Flute and Continuo (BWV 1035); Trio Sonata in G Major for Two Flutes and Continuo (BWV 1039). Leopold Stastny, Frans Bruggen (flutes); Alice Harnoncourt (violin); Nikolaus Harnoncourt (cello); Herbert Tachezi (harpsichord). TELEFUNKEN 6.35339 two discs $15.94.

Performance: Echt!

Recording: Excellent

As we have come to expect from this Telefunken Bach series, the presentation is exquisite: the box is strong and handsome; the historical notes are detailed, copious, and trilingual (German, English, and French); scores are included; and the manuscript of Herbert Tachezi's excellent reconstruction of the first movement of the A Major Sonata is reproduced. The music is performed on original instruments, and articulation and ornaments are executed with the utmost historical accuracy.

All of this is, of course, admirable. But there are some serious musical problems. In the two sonatas with harpsichord obbligato, for example, the performers seem to be at odds about rhythmic alterations. Although both articulate clearly, Tachezi favors rhythmic alterations that conflict with Leopold Explanation of symbols:

= reel-to-reel stereo tape

= eight-track stereo cartridge

= stereo cassette

= quadraphonic disc

= reel-to-reel quadraphonic tape

= eight-track quadraphonic tape

Monophonic recordings are indicated by the symbol The first listing is the one reviewed; other formats, if available, follow it.

Stastny's even flow of notes. Also, some of the tempos are misjudged. In the B Minor Sonata, the first movement sounds nervous be cause of a too-quick tempo, and the slow movement lacks grace and repose because of a pushed andante rather than the largo Bach calls for.

Alice Harnoncourt joins in for the G Major Trio Sonata with a sound that is so deliberately devoid of vibrato and warmth that the result is overwhelmingly disappointing. Musically the two continuo sonatas come off better, especially the one in E Major. Here Stastny, as soloist, apparently feels free to make music the way he likes without worrying about what his peers are up to. The finest reading in the collection is of the G Major Trio Sonata for two flutes and continuo.

Stastny and Bruggen think alike, and the continuo players have no choice but to accompany them without interference.

The album as a whole, then, is for the music history buff only. Presence, projection, and individual interpretation are often completely lacking. The hoops, wigs, and lace have been donned, but the wearers have not yet learned to move naturally in them.

S.L.

BEACH: Sonata in A Minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 34.

FOOTE: Sonata in G Minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 20. Joseph Silverstein (violin); Gilbert Kalish (piano). NEW WORLD NW 268 $6.98.

Performance: Excellent

Recording: Clean but a mite constricted

These sonatas by Amy Marcy Cheney (Mrs. H.H.A.) Beach (1867-1944) and Arthur Foote (1853-1937) are thoroughly representative examples of what the pre-World War I group of American composers centered around Boston was turning out. Within a stylistic framework bounded essentially by Schumann and Brahms, both works display a high level of craftsmanship and by no means lack innate vitality. My own preference between the two is for the Foote. His 1890 sonata dates from his forty-seventh year; regardless of the Brahmsian elements, there are terseness and rhythmic virility in the opening movement and ingenuity in the siciliana scherzo. Brahms is much to the fore throughout the adagio, but Foote the organist-choirmaster emerges triumphantly in the finale, which builds up around a fugato texture and concludes in a splendid blaze of Victorian hymnody.

Mrs. Beach's 1896 work is notable for its predominantly lyrical first movement, a charming lightweight scherzo, and, most especially, the eloquent closing pages of the slow movement. Like Foote, she included a healthy dose of fugal writing to spur the pace of her finale. However, I do find the level of her thematic material occasionally undistinguished compared with Foote's.

In the performances here, Boston Symphony concertmaster Joseph Silverstein displays a small but well-focused tone, ample rhythmic vigor, and right-on-target intonation. Gilbert Kalish negotiates in sterling fashion the highly elaborate piano writing in both sonatas (they are billed as for piano and violin, in the Ger man Classical manner). The recording, done at Columbia's New York studios, is very clean, but I do wish there had been a bit more audible acoustic space. This kind of music can use it. D.H.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

BEETHOVEN: Lieder. Maigesang; Marmotte; Neue Liebe, Neues Leben; Wonne der Wehmut; Sehnsucht; Mit einem Gemalten Band; Freudvoll and Leidvoll; Ich Denke Dein; Aus "Faust" (Flohlied); Urians Reise um die Welt; Die Liebe; Gellert-Lieder, Op. 48, Nos. 1-6; Opferlied; Des Kriegers Ab schied; Das Blumchen Wunderhold; Die Laute Klage. Peter Schreier (tenor); Walter Olbertz (piano). TELEFUNKEN 6.41997 $7.98.

Performance: Excellent

Recording: Excellent

Beethoven wrote nearly a hundred songs, but, except for the An die Ferne Geliebte cycle and a handful of others, few singers seem to favor them. A notable exception is Dietrich Fisch er-Dieskau , whose collection on Deutsche Grammophon 139 197 includes some of the better-known individual songs in addition to the cycle. This new release by tenor Peter.

Schreier duplicates none of Fischer-Dieskau's choices, which means that lieder aficionados who own both discs have about half of Beethoven's total output. Schreier's choices for this disc, labeled Volume 1, are mainly early songs, from the period of about 1793 to 1811, and nine of them are settings of Goethe texts.

I find this a virtually flawless recital. Schreier's tone is not particularly sensuous, but he can achieve exquisite effects through means that are tasteful and unfailingly musical. Very properly, he does not over-romanticize these songs, which are closer in spirit to Mozart than to Schubert. They call for a Mozartian command of tonal purity and sensitive control of dynamics, which the singer supplies in abundance. He also rises with virtuosic ease to certain technical challenges, such as the delicate transitions from full voice to head tone in Neue Liebe, Neues Leben. I would prefer the solid weight of a baritone voice for the solemn utterances of the six Gellert songs (among them the reasonably familiar Die Ehre Gottes aus der Natur), but Schreier surely de livers them as effectively as any tenor can.

Pianist Walter Olbertz, who excelled in the singer's recent Mendelssohn collection, again provides distinguished support, and the engineering is splendid. Texts are provided in German only and there are no notes. Just the same, bring on Volume 2!

G.J.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

BEETHOVEN: Piano Sonata No. 1, in F Mi nor, Op. 2, No. 1; Piano Sonata No. 7, in D Major, Op. 10, No. 3. Sviatoslav Richter (piano). ANGEL 0 S-37266 $7.98.

Performance: Superbly fluent

Recording: Good

Word had it some years ago that Russia's Sviatoslav Richter was not happy recording under studio conditions and that those who wished to document his interpretations for public issue would have to take their chances with his concert performances. But to judge from the production/engineering credits on the jacket of this Angel disc, it appears that he was lured into EMI's Paris studios in the course of a European tour, and the result is as lovely a pair of readings of early Beethoven sonatas as you'll ever hear.

Typically, Richter enjoys making the most of the potential for contrast inherent in the works, so he chooses a very deliberate tempo for the minuetto of Op. 2, No. 1, which enhances the stunning brilliance and dazzlingly smooth passagework he brings to the final prestissimo. In Op. 10, No. 3, the high point is the great largo e mesto slow movement, the first of Beethoven's many profound essays in this vein, and Richter plays it wonderfully.

EMI's Paris recording team has managed the body and presence of the piano tone nice ly, with just enough room coloring to provide a necessary aura of warmth. The slightly hard middle-register tone in forte passages I am inclined to ascribe to the instrument rather than to the performer or producers. A touch of equalization adjustment may help, especially if your listening room happens to be on the live side, as mine is. D.H.

-----------------

Leonhardt Brandenburg Concertos

THE first time I played continuo in Bach's Brandenburg Concertos was an extreme ly startling experience. The orchestra started out bravely, and then, suddenly, the horns went wild; a veritable fox hunt seemed to be going on at their end of the stage. A glance at the score revealed that that was how it was supposed to be; the notated hunting calls and tattoos were right there, even though in all the times I had heard these wonderful concertos I had never really heard the horns sound that way. I never heard them sound that way again until I listened to the superb new ABC/SEON recording of the concertos conducted by Gus tav Leonhardt. It is the clarity of the inner parts that characterizes these discs, and it is, of course, Bach's uncanny treatment of the inner parts that gives these works their very life.

This inner clarity stems both from the use of original instruments and the carefully executed Baroque articulation. In the First Con certo, Bach set up opposing choirs of strings, oboes, and horns. Modern instruments used according to the precepts of modern orchestral blending produce a smooth, homogenized sound. Bach's ideal, however, was not homogeneity but colorful contrast, which can be achieved only with raw-sounding natural horns, cutting oboes, and vibrato-less strings.

Performed by such forces, as it is here, the concerto becomes a lively trialogue. In the Third Concerto the contrast between the choirs is more difficult to bring out, since all three choirs are made up of strings, but in Leonhardt's reading the contrast is as clear as I have ever heard it.

With the various solo instruments in the concertos the problem is not contrast, but blending and balancing the different timbres.

Rarely, for instance, do the recorder and the trumpet of the Second Concerto come off as equal partners, and one often wonders if Bach was not asking for the impossible when he placed them side by side. It is not impossible, however, for this recording accomplishes it.

Perhaps the most ravishing sonority of the entire set is to be found in the Fifth Concerto.

Bach himself was surely aware of this, for there are many passages in the first movement where the harmony and figuration become static and only the sonority carries the music forward. Such moments of limpid clarity are beautifully presented in this performance, and the recording by the German SEON company has caught them perfectly.

Research and experience have taught us that intricate Baroque figuration can be heard best when it is highly articulated. But when the articulated units become too small and detached, because there is too much diminuendo on each unit and too much space between units, the phrase is lost and the result is in compatible with today's tastes. Many con temporary groups that play original instruments fall into this trap; the Leonhardt ensemble does not. Just the right balance is achieved: detail is underlined by articulation, and a long line is produced by a controlling overall sense of phrasing.

In a delightfully whimsical essay included in the notes, Leonhardt modestly points out that we will never know exactly how music was performed in Bach's time and that there fore no performance-including this one can ever be definitive. It is this sort of modesty that makes these records so wonderful.

Nothing is pushed for effect or brilliance; the music expands in its own world unhampered by any pressure from without. The result is a completely believable performance.

Obviously, this new set of the Brandenburgs must be seriously considered no matter how many other fine recordings of the works one already has. And, as a special enticement, there is included a full-size reproduction of Bach's complete autograph score as it was exquisitely copied out and presented to the "Marggraf de Brandenbourg." It is a thrill to follow this music, superbly performed, from the master's own score.

-Stoddard Lincoln

J. S. BACH: The Brandenburg Concertos (BWV 1046-1051). Amsterdam Ensemble, Gustav Leonhardt cond. ABC/SEON AB-67020/2 two discs $19.95.

"a veritable fox hunt seemed to be going on .”

------------------

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

BERLIOZ: L'Enfance du Christ, Op. 25. Janet Baker (mezzo-soprano); Thomas Allen ( bari tone); Eric Tappy (tenor); Jules Bastin (bass); Joseph Rouleau (bass); Philip Langridge (tenor); Raimund Herincx (bass); John Alldis Choir; London Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis cond. PHILIPS 6700 106 two discs; $17.90, 7699 058 $17.90.

Performance: Polished

Recording: Excellent

Since its release in 1961, I have regarded Col in Davis' L'Oiseau-Lyre recording of L'Enfance du Christ as the classic realization of Berlioz's delectable masterpiece--even compared with the distinguished readings by Munch, Martinon, and Cluytens (whose An gel album with De los Angeles and Gedda is no longer listed in Schwann). The new Philips recording of the work, part of that label's admirable Berlioz series, puts the mature Davis in competition with his younger self, albeit with largely different performers under his direction. (Joseph Rouleau, who doubled in the roles of Herod and the Ishmaelite Householder in the earlier recording, sings the latter part in the new one.) Comparing the 1961 Colin Davis performance with that of 1977, I find that the latter offers decidedly more refined orchestral playing (the London Symphony winds are truly wonderful), more polished choral work, and a more dramatically effective balance between the chorus and the rest of the ensemble-particularly in the offstage angelic warnings, hosannas, and alleluias, which sound as seraphically disembodied as anyone could wish. The recording quality too is audibly superior, in overall sonic richness and stereo depth perspective, to that of the 1961 set.

Nevertheless, I am not about to dispose of the earlier L'Oiseau-Lyre album, for not only is it more sharply focused dramatically, but the team of soloists-Peter Pears (in top form), Elsie Morison, John Cameron, and the young Joseph Rouleau-wins hands down over the new Philips team, even though the latter includes the formidable Janet Baker. On the new set Jules Bastin sings Herod's monologue in a beautifully classic manner, but with not a trace of the Moussorgsky-like brooding that Rouleau brought to the 1961 recording.

Eric Tappy represents the classic type of high Gallic tenor, but his voice is too light in texture to elicit the tenderness called for in the "Holy Family by the Wayside" solo, let alone the pathos of the footsore arrival at Sais.

Even if he strained a bit at the top, Pears in the same passages managed to sustain the Gluckian melodic line and also to convey the gripping drama in the subsequent narrative.

For all the beauty of her delivery, Baker sounds like a fully mature woman rather than the frightened young mother depicted so vividly by Morison in the arioso-recitative dialogue between Mary and Joseph as they seek refuge in Sais. Similarly, Thomas Allen seems totally unable to convey Joseph's desperation the way Cameron did in the earlier recording.

To sum up, then, I sense a far greater degree of interaction both among the soloists and between soloists and conductor in the 1961 performance than in the new Philips effort, and it is just this element of interaction that makes the L'Oiseau-Lyre realization truly involving instead of merely enjoyable.

D.H.

BERLIOZ: Te Deum, Op. 22. Jean Dupouy (tenor); Choeur de l'Orchestre de Paris; Choeur d'Enfants de Paris; Maitrise de la Resurrection; Jean Guillou (organ); Orchestre de Paris, Daniel Barenboim cond. COLUMBIA M 34536 $7.98, MT 34536 $7.98.

Performance: Radiant

Recording: Mushy

Sir Thomas Beecham's premiere recording of this work is still in circulation (Odyssey 32 16 0206), and that performance still carries unique power and conviction. But the recording, now in artificial stereo, was made nearly twenty-five years ago, and sonic considerations are especially meaningful in this case.

Indeed, it may be that sonic differences, al most as much as actual interpretive ones, ac count for the different effects made by Colin Davis' 1%9 Philips recording (839 790LY) and the new Barenboim one. For the sake of brevity, it might be said that Davis emphasizes the work's dignity and grandeur and Barenboim its radiance. Both are intense, well organized, obviously committed performances. The new Columbia recording was made in the Eglise de Saint Eustache, the site of the Te Deum's 1855 premiere, and the somewhat over-reverberant acoustics tend to blur some of the lines, frequently making the words sung by the sopranos and the boys' choir all but unintelligible, rendering the orchestral punches a little mushy, and even swallowing up some of the instrumental solos (I found more or less the same effect in SQ playback as in two-channel stereo). The site of the Philips sessions, presumably one of the town halls or large churches regularly used for recording in London, made for a cleaner sonic frame in which every syllable is understandable and the orchestral wallops are not diffused. There are some clear musical advantages in Davis' majestic presentation, too: the London Symphony is a more precise ensemble, than the Orchestre de Paris, Franco Tagliavini's fervor is more appealing than Jean Dupouy's stylish but very cool singing of the solo part, and at the very end Davis leaves the listener with a feeling of noble uplift, while Barenboim's handling of the final bars leaves one wondering if they ought to sound quite so much like the end of Ives' Second Symphony. The Te Deum is a work that deserves far wider circulation than it has so far enjoyed; those who have not made its acquaintance are urged to remedy that oversight-via the Davis recording on Philips.

BRAHMS: A German Requiem, Op. 45; Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a; Tragic Overture, Op. 81. Anna Tomowa-Sintow (soprano); Jose van Dam (baritone); Vienna Singverein; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan cond. ANGEL SB-3838 two discs $15.96.

Performance: Orchestrally superior

Recording: Good except for overture

Karajan's third go at the German Requiem (his earlier essays were in 1948 and 1965) is superior to the others in point of orchestral balance, particularly in the timpani department, but comparison with Klemperer's monumental 1962 reading for Angel finds the Vienna chorus hopelessly weak next to the magnificently trained Philharmonia group.

Only in the evocation of the Last Judgment do the Viennese work up a real head of steam and bring to Brahms' music the elemental power it deserves. As for the soloists, Anna Tomowa-Sintow is no match for Gundula Ja nowitz (in Karajan's earlier DG recording) when it comes to floating the ethereally lovely lines of "Ihr habt nun Traurigkeit," nor does Jose van Dam command the magisterial quality of Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau (in Klemperer's version) in "Herr, lehre doch On the other hand, Karajan's orchestra plays magnificently throughout, and the recording, particularly in the lower end of the frequency spectrum, is absolutely stunning in power and body-which shows up all the more the weakness of the Vienna Singverein.

Karajan's tempos differ only marginally from those of his 1965 DG recording, and recording date, when the Karajan sessions were still being favored with rather church)/acoustics. D.H.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

BRAHMS: Symphony No. 1, in C Minor, Op. 68; Symphony No. 2, in D Major, Op. 73; Sym phony No. 3, in F Major, Op. 90; Symphony No. 4, in E Minor, Op. 98; Academic Festival Overture, Op. 80; Tragic Overture, Op. 81; ...

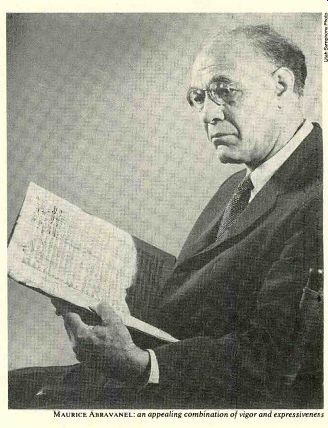

------------- MAURICE ABRAVANEL: an appealing combination of vigor and

expressiveness

...there is somewhat more spontaneity in the handling of dynamics, though the opening "Selig sind" is all but inaudible in my copy.

Oddly enough, Klemperer, usually associated with slow and ponderous pacing, is no slow poke in his handling of this score, being slightly faster than Karajan in all but "Wielieblich sind deine Wohnungen." Indeed, I find far more dramatic urgency throughout the whole of Klemperer's reading, which remains the one I prefer.

Karajan's treatment of the Haydn Variations is as elegant as ever, but I'd like a bit more starkly granitic approach to the Tragic Overture. The two orchestral tracks were evidently recorded in different locales. The rather obtrusive reverberation characteristics in the Tragic Overture indicate an early 1970's Variations on a Theme by Haydn, Op. 56a. Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel cond. VANGUARD CARDINAL VCS 10117/20 four discs $15.92.

Performance: Spirited

Recording: Excellent

The four symphonies, the two overtures, and the Haydn Variations are, except for the two serenades, all the purely orchestral music that Brahms ever wrote (and even the variations are really the composer's own arrangement of a two-piano work). But what a lot of music to be packed into a set of only four discs! Mau rice Abravanel, his Utah Symphony, and Vanguard pack most of it in very well indeed.

The performances give the feeling of Brahms as a poet, as the last optimist. The orchestra is a bit short of first-rate, but, in compensation, Abravanel has been directing it for so long that they make a real team.

There's no heavy, long-beard stuff here; Abravanel's Brahms is "up." It is also rather sensitively worked for both detail and broad shaping. When Abravanel wants to shade the tempo-which he does often and nearly al ways to good effect-the musicians are right there with him. This combination of vigor and expressiveness is appealing, and something of a bargain at the price. A very musical essay by Bernard Jacobson, giving a remarkably succinct explanation of how Brahms' musical mentality actually functioned, is a valuable extra. E.S.

BRAHMS: Violin Sonata No. 1, in G Major, Op. 78; Violin Sonata No. 2, in A Major, Op. 100; Violin Sonata No. 3, in D Minor, Op. 108. Georg Kulenkampff (violin); Georg Solti (piano). RICHMOND 0 R 23213 $3.98.

Performance: Refined

Recording: Variable late-Forties mono

These Brahms sonatas, together with Bruch's G Minor Concerto done with the Zurich Tonhalle Orchestra under Carl Schuricht, were the last recorded performances by Georg Kulenkampff before his death in 1948 at the age of fifty. Kulenkampff had previously enjoyed a distinguished career as soloist and teacher and recorded a goodly portion of the classic violin solo and concerto repertoire, chiefly for Telefunken.

Young Georg Solti had just been appointed conductor of the Munich Opera--a first major step toward his present superstar status. The original English Decca 78's of the Brahms sonatas were transferred to long-play format in 1965 and issued in England when Solti was at the peak of his Covent Garden career.

Kulenkampff plays Op. 78 and Op. 100 in a warm but somewhat over-refined fashion, striking sparks of genuine passion only in the great D Minor Sonata. Solti is an able and, for the most part, sensitive keyboard partner, but he is relegated to the background in the Op. 78 recording. Balances in the other two works are more just. In any event, none of these performances effaces for me the rugged pre-LP versions of Opp. 78 and 100 by Busch and Serkin, or of Op. 108 by Szigeti and Petri, not to mention such more contemporary recordings as those by Suk and Katchen. The re corded sound varies from dim in Op. 78 to relatively good in Op. 108. D.H.

BRUCKNER: Symphony No. 7, in E Major; Symphony No. 8, in C Minor. Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Karl Bohm cond. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 068 three discs, $26.94.

Performance: Forthright

Recording: Very good

Karl Bohm's Dresden recordings of the Fourth and Fifth were among the few complete Bruckner symphonies to appear on 78's; his Vienna Philharmonic concert take of the Seventh (now in Vox set VSPS-14) was one of the first to appear on LP. More than twenty five years went by before he began what was announced as a complete Bruckner cycle with the Vienna Philharmonic for London/Decca, but it got only as far as Nos. 3 and 4. Now, with the same orchestra, Bohm's Bruckner is continuing on Deutsche Grammophon. What is more surprising than the change in affiliation is DG's issuing these particular symphonies only a few months after Karajan's re make of the Eighth appeared on the same la bel (2707 085) and virtually on the eve of the release of that conductor's new DG recording of the Seventh. There is some justification for this duplication of repertoire, in that Karajan recorded the 1887 version of No. 8 while Bohm has done the now virtually standard Nowak edition of the version of 1890. There is also a great deal of pleasure in Bohm's handling of this material and in hearing Bruckner played by the Vienna Philharmonic, whose brass--whether by tradition, instinct, or a combination of both-brings a unique glory to the big proclamative gestures. The very opening of the Seventh Symphony here radiates such unpretentious security, such effortless grandeur, together with a striking vitality, that the listener at once feels a safe and satisfying journey is under way. By and large, that impression has been justified by the end of the Eighth, but one may also have a feeling that the journey has been rather uneventful.

The word that best suits these performances is probably "forthright." There is un questionable integrity and a gratifying absence of interpretive clutter in Bohm's approach, and the playing itself is glorious, set off in a lambent, clear acoustic frame. What is missing is the sense of exaltation one expects from this music. This is not the same thing at all as grandeur of execution and glory of sound (which can be, and here are, exhilarating in themselves). Rather, it is the mystery of what Bruckner is all about, and it requires a bit of indulgence in the way of dramatic shaping, of softer playing here and there than Bohm apparently asks from his orchestra, and of greater subtlety in building to so crucial a climax as that of the great adagio of the Seventh Symphony. Better by far Bohm's noble forthrightness (which is far from bland, and which some will find purifying) than the sort of "Brucknerism" characterized by abrupt gear-shifting and dynamic excesses; but better still the passion that illumines the recorded readings of Haitink, Horenstein, Jochum, and Karajan. R.F.

CARPENTER: Adventures in a Perambulator.

MOORE: The Pageant of P. T. Barnum.

NELSON: Savannah River Holiday. Eastman-Rochester Orchestra, Howard Hanson cond.

MERCURY SRI 75095 $7.98.

Performance: Ingratiating Recording: Excellent This reissue of material from the Mercury archives features American symphonic music at its most winning and agreeable. The stunning Hanson/Eastman-Rochester performance of John Alden Carpenter's Adventures in a Perambulator was out of the catalog for a while.

Now it is back on two labels: the ERA label, backed by Burrill Phillips' Selections from McGuffey's Readers, and this Mercury Gold en Imports release.

Carpenter's contribution is by far the most interesting of the three pieces here. The Harvard graduate who wrote it lived from 1876 to 1951, and when he wasn't managing his father's mill, railway, and shipping supplies business he composed some of the most inventive scores ever produced in this country.

It is a pity that his songs, his orchestral suite Krazy Kat, and his elaborate, high-voltage ballet score Skyscrapers (represented only by a thin, abridged performance on Desto) are not more readily available on records today.

It is certainly good at least to have Adventures in a Perambulator back. Written in 1914, this suite of sketches depicting a baby's day in his carriage is impressionism translated from the French into a distinctly American idiom.

Douglas Moore's The Pageant of P. T. Bar num, the first work still extant by the composer of The Ballad of Baby Doe, evokes episodes in the life of Barnum: here are the country fiddles of his boyhood, a flute solo suggesting the coloratura of Jenny Lind, a mock-military allegro depicting General and Mrs. Tom Thumb, and a full-fledged circus parade, with an out-of-tune clarinet caricaturing the calliope. It is delightful stuff, as is Ron Nel son's Savannah River Holiday, an eight-minute revel replete with the spirit of sum mer. The performances all have that incisive excellence Hanson drew from the Eastman-

Rochester Orchestra, and technically they reflect the high quality of recording achieved by Mercury way back there in the Fifties. The surfaces are flawless. P.K.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

DVORAK: Piano Concerto in G Minor, Op. 33. Sviatoslav Richter (piano); Bavarian State Orchestra, Carlos Kleiber cond. ANGEL S-37239 $7.98.

Performance: Grand

Recording: Quite good

Presumably on the premise that everyone knows who Richter is by now, Angel has printed a jacket blurb about the conductor but

---------------

LULLY--Alceste

JEAN-BAPTISTE LULLY. What a name to conjure with! Born in Florence in 1632, he came to Paris at the age of eleven and had careers as a dancer, violinist, and music director for the king before he turned to opera in 1672.

Louis XIV promptly took the Theatre de "Op era and gave it, lock, stock, and barrel, to Lully. No one else in the history of opera, not even Wagner, ever held such power. The king's patent granted Lully a virtual monopoly on opera in France for the rest of his life.

Working with the poet Philippe Quinault, the designer-engineer Vigarani, and the re sources of the grandest court in Europe, Lully ran the most magnificent show-business establishment of all time. Nothing was left out: there were arias, recitatives, and choruses, huge casts and big orchestras (including the largest string section in Europe, plus ample winds and percussion), extensive dances and ballets, magnificent scenery and costumes, and spectacular stage effects (storms, gods descending, a maritime festival, the seige of a fortress, and the fires of hell all appear in Lully's Alceste). Hollywood at its most "epic" was crude compared to the French opera of le grand siecle.

Lully's musical style derives from the Venetian opera of Monteverdi and Cavalli, which he adapted to the French language and taste. His works were genuine music-dramas: long before Gluck and Wagner, Lully created a total theater in which melody, recitative, poetry, stage action, dance, the visual arts, solo virtuosity, orchestral and choral effects, comedy, and tragedy are intertwined on a grand scale. For three-quarters of a century his operas reigned supreme, only to disappear finally in favor of the works of Rameau and Gluck. They have never come back. Only their reputation-a certain perfume of a distant, heroic time-remains. After his death Lully was violently attacked by the supporters of Italian music, and they succeeded in establishing an image of him as merely the com poser of endless boring recitatives. But the reality-as we hear it on the new, complete Columbia recording of Alceste-turns out to be something quite surprisingly different.

Alceste was one of the earliest, grandest, most successful, and longest-lived of Lully's operas. It was the only one that he based on Greek tragedy, and even then the plot was severely modified to suit the French Baroque taste. Its subject, a favorite of the French, is love in its various shapes and forms. The main plot goes like this: Alceste is about to marry Admetus when she is abducted by Lycomedes . Admetus and his friend Alcides give chase and rescue her, but Admetus is mortally wounded. The god Apollo appears to announce that Admetus must leave this life unless someone else can be found to take his place in death. No one is willing except Alceste, who sacrifices herself. Alcides then boldly descends to the underworld, rescues Alceste, and-though he also loves her restores her in the end to Admetus. Mixed in with this more or less serious plot is a comic subplot involving a young lady whose enthusiastic principle in love is fickleness.

No one else in the history of opera ever held such power

One's first surprise, given Lully's reputation, is the popular character of Alceste's libretto. Like Shakespeare, Lully and his librettists were not afraid to mix the learned and the contemporary, the formal and the emotional, the tragic and the comic, the courtly and the popular-and the mix is pleasing.

Similarly, Lully's music blends the formal and the free, the declamatory and the melodic in a particularly satisfying way.

Of the opera's fall from grace, one can only suppose that the old court tradition seriously deteriorated after Lully's death and every thing began to seem terribly old-fashioned.

The very continuity of the vocal lines, gliding so smoothly from recitative to heightened speech-song to a truly Baroque melodic flowering, must have contrasted sharply with the simplicity and clarity of the new Italian style, in which everything was arranged in neat, easy-to-grasp tunes. To make matters worse, French singing had declined in quality (some say it has never recovered), and performances had become encrusted with layers of fossilized tradition.

To recover Lully's original from under the grime of centuries was certainly no easy task, but it has been admirably accomplished by Jean-Claude Malgoire and an excellent cast.

As is often the case in old vocal music, the men make a stronger impression than the women, particularly the two tenors-John Elwes, an Englishman, and Bruce Brewer, an American-and the versatile Dutch baritone Max von Egmond. The English soprano Felicity Palmer is effective in the (surprisingly small) title role, and the coquette Cephise is charmingly sung by Anne-Marie Rodde. The key element in the success of the recording is Malgoire's direction, for he has recaptured the exquisite flow of vocal and instrumental music with an unerring sense of tempo, phrase, and color. The results are impressive. Lully is not, as we thought, grand and cold. Quite the contrary: he is grand and warm.

-Eric Salzman

LULLY: Alceste. Renee Auphan (mezzo soprano), Nymph of the Seine, Thetis, Diane, grieving woman; Anne-Marie Rodde (soprano), Gloire, Cephise; John Elwes (tenor) Lychas, Apollon, Alecton; Max von Egmond (baritone), Alcide, Eole; Marc Vento (bass), Straton; Francois Loup (bass), Licomede, Cleante, Charon; Pierre-Yves Le Maigat (bar itone), Pheres, grieving man, Pluton; Felicity Palmer (soprano), Alceste; Bruce Brewer (tenor), Admete; others. La Grande Ecurie et la Chambre du Roy, Jean-Claude Malgoire cond. COLUMBIA M3 34580 three discs, $20.98.

--------------------

... not about the soloist. That's an unusual ges ture for a concerto recording, but Carlos Klei ber's contribution here is certainly a major one. The performance is symphonically con ceived and thoroughly integrated between so loist and orchestra from first note to last. It is on a very grand scale, and may strike some listeners as a little larger than life, but its in tegrity and sweep easily sustain the expansive proportions. My one disappointment is the reticent quality of the horn solo that opens the second movement, and even this is almost forgivable in view of the excellent playing by the winds in their exposed passages.

The annotation states that this is the "first time the solo score is played without the sty listic changes subsequently introduced by Vilem Kurz," but Rudolf Firkusny, in his third recording of the concerto (with Walter Susskind conducting, in Vox QSVBX-5135, CT-2145), also went back to Dvotak's original version. Angel's annotator goes to great lengths to find a connection between the per formers and the Czech milieu, whereas a much happier point to be made about the con certo is its adoption at last into the repertoire of musicians who are not Czechs. That Fir kusny (who has done more than anyone else to keep this work alive) and Susskind both grew up in Prague and studied with musicians who had known Dvorak doesn't hurt, of course, and if I were compelled to choose a single recording of the concerto, the greater intimacy and straightforwardness of their au thoritative approach would appeal to me a little more than the more expansive, grander-scaled one of Richter and Kleiber. Both recordings are quite good technically-the Vox a little crisper, the Angel a little warmer-and I would not willingly part with either. R.F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

DVORAK: The Water Goblin, Op. 107; The Noonday Witch, Op. 108; Symphonic Variations, Op. 78. Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Rafael Kubelik cond. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 712 $8.98.

Performance: Very dramatic

Recording. Very good

With this disc Rafael Kubelik completes his traversal for Deutsche Grammophon of the four Dvorak symphonic poems based on folk ballads of Karel J. Erben, the others being The Golden Spinning Wheel, Op. 109, and The Wood Dove, Op. 110. Dvorak's mastery of his musical material for the symphonic poems, particularly in terms of thematic metamorphosis and harmonic coloring, was absolute.

A singularly striking aspect of The Noonday Witch is the composer's use of speech rhythms and dissonance in a way that looks forward to the late works of Leo's Jandeek.

Kubelik has the Bavarian Radio Orchestra performing in a manner reminiscent of the Czech Philharmonic in the palmy days of Va clay Talich. His readings are extraordinarily dramatic, making the London Symphony recordings by the late Istvan Kertesz seem tame indeed in comparison. Dynamic and dramatic contrast also characterizes the Kubelik treatment of the colorful Symphonic Variations, composed nearly twenty years earlier than the symphonic poems. Whether one prefers the dance emphasis in Kubelik's reading or the marvelous flow of the 1969 Colin Davis performance with the London Symphony for Philips (for the moment out of print) is a matter of taste.

The DG sound has both richness and bril liance, though the deepish stereo perspective may offer just a shade less immediate detail than the Kertesz London discs of the sym phonic poems. But for performance of these works, Kubelik is tops. D.H.

FALLA: The Three-Cornered Hat. Teresa Berganza (mezzo-soprano); Boston Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa cond.

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 823 $8.98, 3300 823, $8.98.

Performance: More brilliant than authentic

Recording: Orchestrally excellent

Ozawa and the Bostonians have some hot competition in recordings of Falla's fascinating and witty ballet score about the ups and downs of young love and the discomfiture of middle-aged lust. Ansermet, whose 1962 Lon don recording also has Teresa Berganza as vocal soloist, conducted the world premiere in 1919. In Angel's Fruhbeck de Burgos and Everest's Enrique Jorda, we have Spanish conductors born and bred to the Falla idiom. And then there is the Columbia recording with the New York Philharmonic led by the formidable Pierre Boulez, who in his ballet recordings has displayed a striking feel for the theater along with remarkable musicianship.

I had only the Everest disc on hand for de tailed comparison, but I remember the others, and I would sum up the Ozawa performance as long on orchestral virtuosity and somewhat short on authenticity of feeling. The opening shouts of "Ole!" and the handclapping that set the atmosphere come off rather tamely, as does Mme. Berganza's following solo. The first dance of the miller and his wife is decidedly fast for my taste, the later fandango for the miller's wife alone lacks the nuances of phrasing specifically called for by Falla in his score, the seguidilla for the neighbors' festivities is rather on the languid side-and so on.

JINDRICH FELD--An eclectic, dramatic First Symphony

So, while the orchestral playing is superb and the recording is up to the best Deutsche Grammophon standard, if I were to choose a recording of The Three-Cornered Hat it would be-on the basis of the best combination of sound, vitality of performance, and style Fruhbeck de Burgos' version by a very narrow margin over Boulez. D. H.

FELD: Symphony No. 1. Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Antonio de Almeida cond. Flute Concerto. Jean-Pierre Rampal (flute); Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Vaclav Jirae'ek cond. SERENUS SRS 12074 $6.98.

Performance: Fine

Recording: Symphony good, concerto suspect

This record is my first exposure to the music of Jindfich Feld (born 1925), a Czechoslovak composer noted in Baker's Biographical Dictionary of Musicians for his "chamber music in a neo-Baroque manner." On the evidence offered here, he is a brilliant craftsman, and imaginative too, though not particularly original. Throughout his First Symphony (1970) one is constantly imagining oneself in the do main of some other composer or work, the Shostakovich First Symphony intruding with special prominence among echoes of Bartok, Honegger, Stravinsky, Ravel, and others. It is nevertheless (or perhaps because of these elements) a most attractive work-taut, balletic, a symphony in name only whose five movements (Prologue, Scherzo, Passacaglia, Interludio, Epilogue) have a dramatic thrust suggesting incidental music for a play. Antonio de Almeida, who conducted the premiere in 1972, makes a strong case for the work, and the sound is as fine as the performance.

Jean-Pierre Rampal has spoken with enthusiasm of Feld's Flute Concerto of 1954, and it is likely that this recording dates from the time he played the premiere. It sounds like artificial stereo to me, though it is not so labeled, but it is well managed for all that, with ample smoothness and detail. Actually, the work is not given in its entirety; this extraordinary note appears on the jacket:

"We have included only the first and third movement [sic] of the work because 1.) the total length of the work would demand more record space than Serenus can provide; 2.) the movement is so reminiscent of the sym phony of another great earlier composer that, as capably as it is written, it might be subject to critical misinterpretation, something we believe Feld does not deserve; and 3.) the work has enough slow, moving [sic] parts in the two present movements that a slow movement might actually seem redundant; plus the fact that parts of the second movement are repeat ed in the third." Again, though, it is a really attractive work, with no dead weight (at least in the two longish movements offered here), but with an abundance of echoes and "reminiscences." The writing for the flute is sinuous and silky, and it is effectively contrasted with the generally driving orchestral material in the first movement (where the spirit of Honegger seems ever-present) and the more cantabile tuttis and greater rhythmic and color variety in the third (where Poulenc seems to peep through). The flute has hardly any rests and is called upon for the sort of endurance and big gestures one hardly associates with the instrument-no wonder Rampal loves the work! ( Continued on page 150)

--------------

Kreisleriana

THE simultaneous appearance of three generous helpings of "Kreisleriana" (a fourth, an Elman reissue, is pending from Vanguard) points up once again the enduring appeal of Fritz Kreisler's violin miniatures, virtuoso pieces that dazzle while they delight.

Unlike Paganini, Kreisler never sets up a bravura challenge that cannot be met without sacrificing beautiful sound. No one ever wrote for the instrument more lovingly.

It is part of the virtuosic challenge of the Kreisler repertoire that the pieces be per formed with seeming effortlessness-the debonair charm of Kreisler's own recordings shows the way. This is easier said than done, for the violin writing harbors treacherous reefs under its smooth surface. Mendels sohn's May Breezes is a good case in point. Its basic songfulness would seem to make the ar ranger's lot relatively easy, but Kreisler wrote virtually the entire piece for the violin's D and G strings. To achieve the required cello-like sonorities, the fiddler must constantly play in the highest and most exposed positions-and sound effortless, of course.

Itzhak Perlman in his second Kreisler al bum manages all this and more with stunning ease. He plays not only elegantly but also in the Kreisler spirit of romantic abandon, caressing his phrases and fearlessly using Kreisler's brand of old-fashioned portamento. But his innate taste allows for no exaggerations: no jondo emotionalism in Albeniz, no bearing down on the G string in Mendelssohn, not even an excess of Viennese schmaltz.

Technically, he could not be more impressive, right down to the treacherous Devil's Trill cadenza.

Eugene Fodor has a flashier style. His technique may be as formidable as Perlman's, but he does not round off his phrases with the latter's elegance and caressing touch (a rather over-assertive Old Refrain here is a good case in point). There is plenty of dazzle and even sweetness of tone, but the spiritual identification with the Kreisler world is missing.

That elusive quality is decidedly present in the playing of Beverly Somach, the erstwhile prodigy who with her "Homage to Fritz Kreisler" returns to concertizing after several years' absence. I enjoy the affecting lyricism FODOR she brings to the music, and she meets the technical challenges too, but not quite with the triumphant ease of her two colleagues.

There are surprisingly few duplications among the three discs (though Perlman's first Kreisler album, Angel S-37171, duplicates many of Fodor's choices). The accompaniments are good in all three collections, and all are well engineered, though Angel's exemplary balance gives the Perlman recording a slight edge.

-George Jellinek

ITZHAK PERLMAN PLAYS FRITZ KREISLER, ALBUM 2. Tartini/Kreisler: Sonata in G Minor ("The Devil's Trill"). Poldini/ Kreisler: Dancing Doll. Wieniawski/Kreisler: Caprice in A Minor.

Trad. (arr. Kreisler): Londonderry Air. Mozart/Kreisler: Rondo from the "Haffner" Serenade. Corelli/Kreisler: Sarabande and Allegretto. Albeniz/Kreis ler: Malagueria. Heuberger/Kreisler: Midnight Bells. Brahms/Kreisler: Hungarian Dance in F Minor. Mendelssohn/Kreisler: Song Without Words, Op. 62, No. 1 ("May Breezes"). Itz hak Perlman (violin); Samuel Sanders (piano). ANGEL 0 S-37254 $7.98.

EUGENE FODOR PLAYS FRITZ KREISLER. Kreisler: Praeludium and Allegro (in the Style of Pugnani); Sicilienne and Rigaudon (in the Style of Francoeur); Menuet (in the Style of Porpora); La Chasse (in the Style of Car tier); Recitativo and Scherzo; The Old Re frain; Caprice Viennois; Tambourin Chinois; Schtin Rosmarin; Liebesfreud; Liebesleid; La Gitana. Eugene Fodor (violin); Stephen Swedish (piano). RCA ARL1-2365 $7.98.

BEVERLY SOMACH: Homage to Fritz Kreisler. Tartini/Kreisler: Sonata in G Minor ("The Devil's Trill"); Variations on a Theme of Corelli. Gluck/Kreisler: Melodie from Orfeo ed Eurydice. Mendelssohn/Kreisler: Song With out Words, Op. 62, No. 1 ("May Breezes"). Kreisler: Praeludium and Allegro (in the Style of Pugnani); Andantino (in the Style, of Padre Martini); Liebesfreud; Liebesleid. Beverly Somach (violin); Fritz Jahoda (piano). MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 3612 $4.95 (plus $1.25 handling charge from Musical Heritage Society, 14 Park Road, Tinton Falls, N.J. 07724).

-----------------

Now I'm really curious about that omitted slow movement, and (bearing in mind that one man's "eclectic" is another's "derivative") I'd like to hear more of Feld's music-which Serenus will be offering, apparently, since this disc is labeled "Volume 1." R . F.

FOOTE: Sonata in G Minor for Piano and Violin, Op. 20 (see BEACH) GOUNOD: Faust. Montserrat Caballe (so prano), Marguerite; Giacomo Aragall (tenor), Faust; Paul Plishka (bass), Mephistopheles; Philippe Huttenlocher (baritone), Valentin;

Anita Terzian (mezzo-soprano), Siebel; Joce lyne Taillon (mezzo-soprano), Marthe; Jean Brun (baritone), Wagner. Chorus of the Rhine Opera; Strasbourg Philharmonic Orchestra, Alain Lombard cond. RCA FRL4-2493 four discs $31.98.

Performance: Vocally compelling

Recording: Very good

In "Essentials of an Opera Library" (October 1977 STEREO REVIEW), George Jellinek said that this new Faust (he had heard the advance pressings) would not replace the old De los, Angeles/Gedda/Christoff/Cluytens Angel re cording as his favorite. Well, I would agree, but there are more than a few things to be said for the new RCA recording nevertheless.

Montserrat Caballe's Marguerite is special: sweet, gentle, exquisite. There's no passion, but then there's not much real depth in the role to start with. Her portrayal is close to a certain kind of perfection; almost the only jar-ring note comes at the very end, when Marguerite suddenly and astonishingly throws Faust out so she can be suitably saved. Nothing in Caballe's performance prepares us for this sudden transformation of Marguerite from virgin to avenging angel.

Paul Plishka is a classic Mephistopheles with a dark, firm bass. Giacomo Aragall, a big, new talent, has a magnificent tenor voice that is a bit unpolished musically (compared with Gedda's, at any rate) but is certainly compelling. The weakness of the cast is the Siebel; Anita Terzian is not on a level vocally with the rest.

The orchestral forces are not first-rate, and Alain Lombard is not a great genius of the po dium, but these faint damns are not far from praise. Lombard is a fluent and highly compe tent practitioner, and he gets highly compe tent results out of the Strasbourg musicians.

This is, after all, Gounod. Faust is a work with a strong opening and much striking and beautiful music to follow. But there is also a steady and inexorable slide into sentiment, and Lombard's own enthusiasm seems to rise and decline on that same curve. He is a supple, sure-handed, but somewhat slippery craftsman who threads his way through Gou nod's pious sexiness (or is it sexy piety?) with ease, but never lifts us up beyond it. E.S.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

GRIFFES: Piano Sonata; Three Tone-Pictures, Op. 5. RAVEL: Le Tombeau de Couperin. Susan Starr (piano). ORION ORS 77270 $7.98.

Performance: Superb

Recording: Very good

Susan Starr, trained at the Curtis Institute in Philadelphia, is yet another of the crop of younger-generation pianists to be reckoned with-and not just on the basis of virtuoso equipment but of innate musicality as well. I especially enjoyed Starr's handling of the Ravel masterpiece, inasmuch as she gives its poetic essence fully as much attention as its neo-Classic aspects. The music gains enormously thereby. And if it's sheer brilliance you're after, her playing of the final toccata will stand up against any other performance available on discs.

But the Griffes side of the disc gives me even more pleasure. I have been a strong par tisan of the fierce and power-packed sonata ever since I heard Harrison Potter play and record the piece back in the 1930's. There was a spate of early LP recordings of the work in the 1950's, but no stereo version appeared un til 1976, when the enterprising British pianist Clive Lythgoe recorded it for Philips as some thing of a Bicentennial tribute. Miss Starr's performance of the sonata is dynamic and brilliant, and an added attraction of her disc is the first stereo recording of the Op. 5 Tone Pictures-The Lake at Evening, The Vale of Dreams, and The Night Winds-in their original piano version (the woodwind-piano-harp arrangement was issued in 1976 by New World Records). In contrast to the Scriabin influenced style of the sonata, the Tone-Pictures are delicate and masterly impressionist essays. Miss Starr's playing is for me beyond criticism throughout, and the recording quality is altogether first-rate. D.H.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

HANDEL: Sonatas for Oboe and Continuo in G Minor, Op. 1, No. 6, and in C Minor, Op. 1, No. 8; Trio Sonatas for Two Oboes and Continuo No. 2, in D Minor, and No. 3, in E-Hat Major. Ronald Roseman and Virginia Brewer (oboes); Donald MacCourt (bassoon); Timothy Eddy (cello); Edward Brewer (harpsichord). NONESUCH H-71339 $3.96.

Performance: Sensual

Recording: Clear

Ronald Roseman brings to these sonatas of the youthful Handel the kind of Italianate ex uberance that went into their composition.

Treating them more as sketches for controlled improvisation than as specific notations for exact readings, Roseman spins garland after garland of sensuously ornate phrases, espe cially. in the slow movements. Performed in a seamless legato with a rich tone, the music emerges with the effect of inspired rhapsody Although the amount of ornamentation is nec essarily curtailed in the trio sonatas, Virginia Brewer is an excellent foil and expertly tosses back whatever challenges come her way.

The balance of the ensemble is excellent, and the use of a cello continuo for the solo so natas and a bassoon for the trio sonatas is an admirable notion. Edward Brewer's harpsi chord realizations are beautifully wrought and discreetly performed, the hallmark of good continuo playing. Although the trio sonata is to Baroque chamber music what the string quartet is to Classical chamber music, there are very few really good recordings derived from this vast and rich repertoire. This disc is a valuable addition to the catalog. S.L.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

JANACEK: Katya Kabanovi. Nadeida Kni plova (mezzo-soprano), Marfa Kabanova; Vladimir Kregik (tenor), Tichon; Elisabeth Soderstrom (soprano), Katya Kabanova; Dalibor JedHata (bass), Dikoj; Petr Dvorskyt (ten or), Boris; Libi)se Marova (soprano), Var vara; Zdenel Svhla (tenor), Villa; others. Vienna State Opera Chorus; Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra, Charles Mackerras cond. LONDON OSA 12109 two discs $15.96, 5-12109 $15.96.

Performance: Very good

Recording: Excellent

By the time Leo's Janieek began Katya Kaba nova, his sixth opera, in 1917, his style was fully formed; it is characterized by brief, fragmentary vocal melodies growing out of speech patterns, a combination of parlando devices and folkloric elements, and a frequent use of motivic reiteration. The sparse orchestration occasionally takes on an unexpected brilliance, which, combined with biting and slashing sonorities, can result in unforgettably striking effects. The curious thing about Jana Zek is that what may initially seem like a primitive device will often turn out to be cunningly sophisticated.

Katya Kabanovd is based on Alexander Ostrovsky's play The Storm. (Tchaikovsky, who often turned to Ostrovsky's writings for inspiration, had written a programmatic con cert overture on the very same subject.) The plot: caught in an unhappy marriage and sadistically hounded by an evil mother-in-law, Katya seeks solace in a love affair, but she cannot live with her guilt and destroys herself.

Unquestionably, this makes for powerful theater despite the highly condensed and not very skillful libretto (Janadek's own).The river Volga and the gathering storm are used with great tone-painting art to provide a frame for the catastrophe. There is a sense of inevitability to the drama, and though the libretto does not allow for enough character development, the conflicts are real and full of impact.

In this performance the impassioned con ducting of Charles Mackerras (pupil of the great Vaclav Talich and an authority on this music) must be singled out for special praise.

He communicates the tenderness as well as the power of Jangek's quirky writing with a sure hand, drawing magnificent sounds from the Vienna Philharmonic. In the title role, Elisabeth Soderstrom, that exceptional singing actress, seizes our sympathy with Katya's yearning first-act aria and never lets go. More over, as the only non-Slav among the principals, she has mastered the Czech sounds remarkably well.

The other members of the cast appear thoroughly at home with the idiom. They form a very strong ensemble with certain standouts:

Nadelee Kniplova as the monstrous mother in-law is formidable yet laudably short of overdrawing the part, Petr DvorskY is convincing as the decent and not too bright lover caught in the triangle, and Dalibor Jedliela is colorful and sonorous as Boris' uncle.

Like all of Janadek's operas, Katya Kaba nova cannot be related to any Italian, French, or German models. Its closest frame of reference is the same composer's earlier Jenufa.

Of the two I find Katya Kabanovci mere successful. It may not instantly conquer you, but it will grow on you. G.J.

+++++++++

-------------------

I CANNOT say that the new London recording of Verdi's Il Trovatore conducted by Richard Bonynge lives up to the promise of its blockbuster cast-it includes not only Joan Sutherland but also Luciano Pavarotti, Marilyn Home, Nicolai Ghiaurov, and Norma Burrowes. And yet, like the flawed but irresistible opera itself, it will undoubtedly have many partisans despite some few justifiable critical reservations.

Things begin-disappointingly-with a lifelessly conducted first scene in which Nicolai Ghiaurov sings the part of Ferrando well enough but not with the commanding authority he has displayed on past occasions (when, for moments, he could make us believe we were listening to operas named Ramfis or Timer). Bonynge has some fine moments later, such as the "Mal reggendo" duet and the difficult ensemble at the end of Act II, which he holds together admirably. But his overall leadership is inconsistent: the Anvil Chorus starts out too fast and settles into an effective pace only in the repetition, the Miserere is too languid, and the final scene, though somewhat better, still lacks the right urgency.

I find Luciano Pavarotti's Manrico virtually flawless. Except for "Di quella pira," this is really a lyric role, and from the very opening off-stage serenade Pavarotti imparts the prop er melancholy coloration to his music. In all his big moments, and there are many, he sings meltingly, with elegantly turned phrases. The single martial outburst is also delivered in a manner that silences criticism; let us hope that such vocal escapades do not damage the tenor's invaluable equipment.

Joan Sutherland's Leonora is more debat able. It is a pleasure to hear the part sung with note-perfect accuracy, neatly executed trills, and no compromise whatever in the florid requirements. Temperamentally, though, Sutherland cannot manage the transition from the aloof and dignified Leonora of the early scenes to the courageous and determined woman of Act IV. This, combined with her improved but still indistinct pronunciation, creates merely admirable instances of vocal display where involved dramatic singing is called for. But that vocal display is consistently beautiful in tone, a quality that simply cannot be dismissed.

If Verdi intended to make Azucena the central character in this opera, he must have had a mezzo with Marilyn Horne's extraordinary gifts in mind. She offers singing of all-out intensity and discriminating intelligence: her reverie-like approach to "Stride la vampa" and "Ai nostri monti" is not only right but also beautifully brought off. At forte levels, however, her vibrato sometimes takes the tone off the indicated pitch, to the detriment of an otherwise vital portrayal. Ingvar Wixell, a splendidly resonant, vigorous, and stylistically assured Verdi baritone, also lacks the smooth flow of consistently centered tone that would make his Count di Luna truly distinguished. Norma Burrowes presents an exceptionally good Ines, the other comprimarios are adequate, and, except for occasional im-precisions, the chorus does its work well.

This is the most complete Il Trovatore on records. The ballet sequence Verdi inserted for the opera's 1857 Paris premiere is dramatically irrelevant and disproportionately long, but in its own terms it is very good, and Bonynge conducts it well. There are also various restored cuts and usually omitted second verses to which Sutherland, for her part, adds tasteful embellishments. (The appropriate ness of the latter is debatable but certainly defensible. It would be interesting to read Bonynge' s thoughts on the matter.) The engineering is especially praiseworthy for its clear reproduction of the vocal ensembles. I recommend this set not as the "best" Trovatore but, in the absence of a uniformly superior stereo version, one of the most valid alternatives.

-George Jellinek

VERDI: Il Trovatore. Luciano Pavarotti (tenor), Manrico; Joan Sutherland (soprano), Leonora; Marilyn Horne (mezzo-soprano), Azucena; Ingvar Wixell (baritone), Count de Luna; Nicolai Ghiaurov (bass), Ferrando; Norma Burrowes (soprano), Ines; Graham Clark (tenor), Ruiz; others. London Opera Chorus; National Philharmonic Orchestra, Richard Bonynge cond. LONDON OSA 13124 three discs $23.94. "I find Pavarotti's Manrico virtually flawless. ."

-------------------

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

KALINNIKOV: Symphony No. 1, in G Minor. State Academic Orchestra, Yevgeny Svet lanov cond. COLUMBIANELODIYA M 34523 $7.98.

Performance: Enchanting

Recording: All right

Svetlanov came surprisingly close to the standard set by Sir Thomas Beecham in his recent recording of one of Beecham's special ties, the Balakirev Symphony No. 1 (Melodiya/Angel SR-40272), and this enchanting realization of the Kalinnikov First strikes me as the finest thing he has done on records so far.

There is a firm but subtle hand in control here, encouraging the various wind soloists in particular to shape phrases freely and alluringly and infusing the proceedings with an altogether captivating air of spontaneity. The Borodinish second theme in the first movement has a fine spring to it, and the andante, with the tasteful caressing of Kalinnikov's imaginative writing for harp, solo oboe, English horn, and clarinet (in that sequence), is sheer poetry. But the entire performance may be so described. The final movement is taken at a lick that will strike some listeners as excessively fast for the allegro moderato marking, but it works beautifully, generating a sweeping excitement that is ever so much more winning than the deliberately paced monumentalism usually visited on this dazzling piece. The recording could be richer, and the orchestra (probably the same one usually billed as the USSR Symphony Orchestra) shows some rough spots, but the shortcomings are easily overlooked amid the overall persuasiveness of the performance=which stands up splen didly in repeated hearings. R.F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

LISZT: Piano Sonata in B Minor; Mephisto Waltz; Transcendental Etudes No. 5 ("Feux Follets") and No. 12 ("Chasse-neige"). Janina Fialkowska (piano). RCA FRL1-0142 $7.98.

Performance: Remarkable

Recording: Good

On this French-recorded debut disc we have a brilliantly gifted young artist (with her share of competition laurels, too) whose musicality fully matches her seemingly limitless technical brilliance. Her Mephisto Waltz and Chasse-neige are fine performances indeed, but it is the gigantic B Minor Sonata that pro vides pretty much the ultimate test of virtuosity, endurance, and musicality. I can well un derstand the enthusiasm of Artur Rubinstein for Miss Fialkowska's performance of this work in the 1974 Israel competition bearing his name. Without question, the most impres sive aspect of her reading is an unerring sense of proportion, a feeling for the larger drama, that allows her to achieve a wonderfully satisfying sense of climax in the famous grandioso chorale-like episode. And yet she slights no detail of ornamentation and passagework. Everything falls into place musically and dramatically from beginning to end of this performance, which for me takes its place among the half-dozen or so really distinguished interpretations currently in the catalog. To hear Liszt with the poetry as well as the glitter is a fairly uncommon experience. Here is one disc that truly fills the bill. The recorded sound is full bodied and brilliant, if now and then just a mite confined. D.H.

MOLIQUE: Concerto in B Minor for Flute and Orchestra, Op. 69.

ROMBERG: Concerto in B Minor for Flute and Orchestra, Op. 30. John Wion (flute); orchestra, Arthur Bloom cond.

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY MHS 3551, $4.95 (plus $1.25 handling charge from Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 14 Park Road, Tinton Falls, N.J. 07724).

Performance: Scruffy

Recording: Thin

These two mid-nineteenth-century flute con certos are musically akin to the Hummel piano concertos and the Spohr clarinet concertos. Their gesture is pompous and serious, their form overblown, and their idiom padded with endless figuration and embroidery. But despite their old-fashionedness, they offer a fine flutist great moments of virtuosic revelry.

John Wion is a good flutist who employs a seamless legato appropriate to the style and, for the most part, gets around easily. There are, however, times when his pitch goes awry or his breath runs out and rhythmic smooth ness vanishes in the interest of simply getting through long and difficult passages.

The orchestral sound is far thinner than that required in music of this bombastic period, and I wonder if this obvious pick-up group had sufficient rehearsals to give a confident reading and full support. Nonetheless, the concertos make a welcome addition to the early Romantic recorded repertoire, and John Wion deserves some credit for digging them up and having the patience to learn them.

S.L.

MOORE: The Pageant of P. T. Barnum (see CARPENTER) RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT MOZART: Piano Concerto No. 14, in E-flat Major (K. 449); Piano Concerto No. 23, in A Major (K. 488). Ivan Moravec (piano); Czech Chamber Orchestra, Josef Vlach cond. SuPRAPHON 1 10 1768 $7.98 (from Qualiton Rec ords Ltd., 65-37 Austin Street, Rego Park, N.Y. 11374).

Performance: Poetic

Recording: Good

The stunning recording Moravec and Vlach made of the Concerto No. 25 with the Czech Philharmonic (Vanguard SU-11, reviewed here in February 1976) encouraged me to hope for more Mozart from the same team, and this pair of performances is every bit as distinguished as that earlier one. The K. 449 concerto lends itself especially well to the chamber-music approach it receives here exquisitely balanced, marvelously integrated, giving one the feeling that Moravec and every member of the orchestra are actually listening to each other and playing as beautifully as they can for each other's pleasure. Moravec and Vlach take the adagio of K. 488 very slowly indeed; it is by no means heavy or thickened, though, but is tempered by the same aristocratic restraint as the arias of the Countess in Figaro, to whose music this con certo, its slow movement in particular, is so intimately related. The outer movements, too, are somewhat restrained, but never at the ex pense of their innate vitality. Both of the Ser kins have given us similarly distinguished (and more imaginatively coupled) versions of K. 449, and Brendel and Pollini are equally persuasive in K. 488. But those to whom this particular coupling appeals, or whose enthusiasm for exceptional Mozart playing is not dimmed by the prospect of a duplication or two, may regard purchase of this well- recorded disc as one of the safest investments they are likely to make. R . F.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

MOZART: Violin Concerto No. 3, in G Major (K. 216); Violin Concerto No. 5, in A Major (K. 219, "Turkish"). Jose Luis Garcia (vi olin); English Chamber Orchestra, Jose Luis Garcia cond. HNH 4030 $7.98 (from HNH Distributors, Ltd., P.O. Box 222, Evanston, III. 60204).

Performance: Superb

Recording: Flawless

These two Mozart violin concertos have had more than their share of outstanding recorded performances. But Jose Luis Garcia, long associated with the English Chamber Orchestra, especially in Baroque repertoire, doubles as soloist and conductor and comes up here with as fine a realization of these delectable works as I have heard anywhere. His tone has sweetness and warmth without ever becoming cloying, and it is quite clear throughout the orchestral tuttis and ritornellos that conductorially he can keep things moving in an effortless ebb and flow. Especially in the slow movements, he melds the solo and orchestral dialogue into a truly organic whole. Superb recorded sound and noiseless playing surfaces add to a production that gives unalloyed pleasure from start to finish. D. H .

NELSON: Savannah River Holiday (see CARPENTER) PETROV: Songs of Our Days, Symphonic Cycle; Poem for Strings, Organ, Four Trumpets, and Percussion. Leningrad Philharmonic, Arvid Yansons cond. COLUMBIA/MELODIYA M 34526 $7.98.

Performance: Heavy going

Recording: Very good

Andrei Petrov, born in Leningrad in 1930, is one of the younger composers in the Soviet Union seeking recognition in the face of the dominance of the modern big six: Prokofiev, Shostakovich, Khatchaturian, Kabalevsky, Miaskovsky, and Gliere. In 1968, Petrov wrote a letter to a Soviet newspaper suggesting that it was time some attention was paid to works by younger men. Well, this Soviet re cording introduces us to Petrov's own work.

He is a skilled orchestrator and an unabashed melodist and colorist deeply influenced by the work of the generation he is hoping to sup plant in the concert hall, but there is some thing essentially banal and mechanical in the musical episodes that make up Songs of Our Days-though the charm of the pipings and the toy march in the section called "Child hood" indicates what he might achieve in an unpretentious way if he were to take himself less seriously. Yet there is real strength and power in the Poem for Strings, Organ, Four Trumpets, and Percussion dedicated "to the memory of those who died during the blockade of Leningrad." This is restless, belliger ent music of impressive formal dimensions, and it makes me think that Petrov might yet be a worthy heir to Shostakovich himself who, however, lived to outgrow this type of rhetoric in the subtler scores of his later years. Perhaps it is not too late for Petrov, not yet fifty, to outgrow it as well. The performances by the Leningrad Philharmonic under Arvid Yansons are hard-driving and heavy handed, but given the leaden weightiness of these scores it is hard to imagine how they could have been otherwise. P. K .

PUCCINI: Gianni Schicchi (see Best of the Month, page 94)

PURCELL: Funeral Music for Queen Mary.

Anthems: Hear My Prayer, O Lord; Remem ber Not, Lord, Our Offences; Rejoice in the Lord Alway; My Beloved Spake; Blessed Are They That Fear the Lord. Choir of King's College, Cambridge; Philip Jones Brass Ensemble; Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Philip Ledger cond. ANGEL 0 S-37282 $7.98.

Performance: Churchy

Recording: Resonant

If the first side of this album plunges you into a fit of depression with its unmitigated gloom, ...

HENRY PURCELL Joy in the choir stall

... the second side will return you to a normal state of cheerfulness with its joyous verse anthems that so pleased the restored monarch Charles II. As one expects from the Choir of King's College, the choral sound is clear, but it is rather on the subdued side. Though the blend is particularly rewarding in the homo phonic passages, the sound loses its richness in many of the contrapuntally conceived sections. In an effort to bring out various points of imitation and interesting individual lines, Ledger allows the sound to fall apart and be come scruffy at times. The solo work by the countertenor, tenor, and bass is fine, but the various boy sopranos seem inadequate.

Perhaps the most frustrating aspect of this performance is the churchy approach to the music. Purcell was a full-blooded, lusty com poser equally at home in chamber, church, or theater. He used much the same style for each, underscoring the meaning of the words with his music. Joy is joy whether it is in the choir stall or on the boards, and it must not be played down just because the text is biblical; Solomon's amorous expressions are just as sensuous as any uttered by rakes and shepherds. The King's College Choir seems to for get this, and as a result Purcell's passionate musical language suffers from unnatural restraint and understatement. S.L.

RAVEL: Le Tombeau de Couperin (see GRIPPES)

RIETI: Conundrum, Ballet Suite. Harkness Ballet Orchestra, Jorge Mester cond. Sestetto pro Gemini. Gemini Ensemble. Second Avenue Waltzes. Elda Beretta, Maria Madini Moretti (pianos). SERENUS SRS 12073 $6.98.

Performance: Fluent

Recording: Good

It brought me up short to see "The Music of Vittorio Rieti, Vol. VI," printed across the top of the jacket, but this is indeed the sixth generously filled disc of Rieti's works in various forms to be offered by Serenus in the last few years. The three works here are as ingratiating and solidly wrought as the better known Harpsichord Partita (Sylvia Marlowe's remake of this is now preserved on CRI 312SD, together with the Harpsichord Con certo). Gold and Fizdale's recording of the Second Avenue Waltzes (1941) on an early Columbia LP (ML 2147) has become a collector's item, so this new recording of the work, delightfully played by two Italian pianists, is especially welcome. The Sestetto pro Gemini (for flute, oboe, two violins doubling viola, one cello, and piano) was written only a few years ago for a Dutch chamber group whose personnel includes two sets of twins from the same family; of its four brief movements, the vivacious second and lyrical third are especially intriguing, but all four are graced with real tunes and lovely, fresh colors. These would seem to be the most prominent qualities of Rieti's music, as they are again in the Conundrum ballet suite of 1964, whose dramatic episodes and propulsive momentum seem to contradict the information that it was composed without a specific scenario. All three performances are fluent, involved, and of a quality to delight any composer's heart, and the recording itself is quite good. Altogether a handsome and enjoyable package.

R.F.

ROMBERG: Concerto in B Minor for Flute and Orchestra, Op. 30 (see MOLIQUE) SCHUBERT: Lieder (see Collections-Ian Partridge)

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT

R. STRAUSS: Don Juan, Op. 20; Macbeth, Op. 23. Dresden State Orchestra, Rudolf Kempe cond. SERAPHIM 0 S-60288 $4.98.

Performance: Splendid Recording: Vivid This would appear to be the first recording of Macbeth since Henry Swoboda's 1950 version for Westminster, which means it is only the second ever; it is curious that the work could have been neglected for so long, but then Strauss himself seems not to have bothered with it much either in conducting his mu sic. It is an early work, as the opus number indicates, antedating Don Juan by a year in its original form, and even the revision made two years later shows more Lisztian characteris tics than one finds in Strauss' other tone poems. Both historically and for its own worth, it is too valuable a piece to be abandoned, and it could not be in better hands than it is here.

The Dresden orchestra, Strauss' own favorite, is justifiably proud of its unique tradition in performing his music, and Kempe too was more closely associated with the works of

Strauss than with those of any other composer. His magnificent cyclic of all Strauss' orchestral works, from which these two splendid performances are drawn, is surely his finest memorial, and Angel is more than generous in making portions of it available on the low-price Seraphim label. Both sides shine with authority, conviction, and commitment, and the sound has a burnished glow more mellow than brilliant, but agreeably rich and well defined. In view of the uniqueness of the coupling, this Don Juan might head the list of the versions now available. R.F.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Piano Music Humoresque, Op. 10, No. 2; By the Hearth, Op. 37a, No. 1; Impromptu, Op. 72, No. 1; Valse, Op. 40, No. 8; Nocturne, Op. 19, No. 4: Chanson Triste, Op. 40, No. 2; Christmas, Op. 37a, No. 12; In the Troika, Op. 37a, No. 11; Barcarolle, Op. 37a, No. 6; Durnka, Op. 59; Russian Dance, Op. 40, No. 10; Scherzo, Op. 40, No. 11; Song Without Words, Op. 2, No. 3; Harvest, Op. 37a, No. 8; Song of the Lark, Op. 37a, No. 3. Danielle Laval (piano). SERAPHIM S-60250, $4.98.

Performance: Pretty

Recording. Good

There was a big demand for do-it-yourself piano music in the nineteenth century, and Tchaikovsky composed quite assiduously and successfully for this market. His own style and inclinations made him the perfect master of the lytical small form. His innumerable salon and genre piano pieces combine the poet-is/meditative style of the early Romantics with the picturesque genre piece of the late nineteenth century. Silent-film pianists ripped off this music and almost killed it; no one has taken it seriously for a very long time.

Nevertheless, its appeal can be as strong as ever; a comeback was inevitable. Danielle Laval, a young French pianist, plays this mu sic without affectation and with real charm.

She is not brilliant or flashy, but there is warmth and just the right touch of sentiment in her performance. Not only is this disc en gaging to listen to but it should send those home pianists still left among us rushing back to the keyboard, Tchaikovsky scores in hand.

E.S.

RECORDING OF SPECIAL MERIT VIVALDI: Flute Concertos, Op. 10, Nos. 1-6.

Stephen Preston (flute); Academy of Ancient Music. L'OISEAU-LYRE DSLO 519 $7.98.