- EDITORIALLY SPEAKING, WILLIAM ANDERSON

- LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

- INSTALLATION OF THE MONTH, RICHARD SARBIN

- TECHNICAL TALK, JULIAN D. HIRSCH

- THE POP BEAT, PAULETTE WEISS

- GOING ON RECORD, JAMES GOODERIEND

- THE OPERA FILE, WILLIAM LIVINGSTONE

EDITORIALLY SPEAKING, WILLIAM ANDERSON

MANDATORY RETIREMENT

THE chief failing of critics, says author/conductor/critic Robert Craft in his aptly titled book Prejudices in Disguise (Knopf, 1974), is that they don't know when to retire: "The mortal kind grows stale very quickly, after a year or so at the most . . the critic confines his subject more and more to him self.- It is a failing, thank goodness, that Craft apparently shares, for his Current Convictions, a hard-to-put-down collection of opinionated critical essays on subjects variously musical, literary, and sociological (Mary Hartman?!) has just been published by Knopf.

It is true that criticism is inescapably subjective, mere prejudice disguised or made plausible, but that is no reason for an able critic to retire after indulging it for only a year or so-let his audience do that. Those who have been persuaded, either by irrefutable logic or natural sympathy, to make his opinions their own do not need further tutelage.

Those who reject his opinions should find themselves a more congenial teacher. A critic should retire only when it becomes clear that he can no longer replenish his audience.

What we want from critics are strong opinions well argued and well expressed. It de lights me when a critic, grown older and bolder in office, drops the polite mask of scholarly omniscience, the pose of detached objectivity, in favor of the disquieting candor of those who have nothing to lose. There is a danger in long incumbencies, however, even for critics, for many of them tend to develop Golden Age Syndrome, turning critical of the decayed times in which they live and prattling invidiously about how Melba, Nikisch, or Hofmann.

(ah, there were giants in those days!) would have done it.

But those are opinions too, and they have their supporters, as a miff y letter from a reader recently reminded me. It seems that critic Richard Freed, in reviewing two new recordings of the Dvorak A Major Quintet (one by Emanuel Ax and the Cleveland Quartet, the other by Rudolf Firkusny and the Juilliard) in our September issue, failed to mention a 1963 release, by Clifford Curzon and the Vienna Philharmonic Quartet, that is just beginning its fifteenth year in the catalog.

There are, as a matter of fact, two Curzon recordings still in the catalog, one with the Vienna group (London CS 6357) and another with the Budapest Quartet (Odyssey 32260019, an even older mono recording).

This popular work is also represented in performances by pianists Stephen Bishop, Jacob Lateiner, Artur Rubinstein, Gyorgy Sandor, and Peter Serkin. That makes a total of seven old recordings critic Freed might have com pared with the two new ones and didn't. Why didn't he? First, richly comprehensive though I know his record collection to be, I doubt that he had all seven of them on hand, and rounding up the missing ones would almost certainly have meant a month's delay in bringing readers the good news of the two new ones (they are both splendid recordings). Second, the review was just that-a review-and not an article about all the available recordings of the Quintet. (If reviews of current releases had to be burdened with complete catalog surveys-imagine what that would mean for Beethoven's Fifth!-reviewers would run out of time and we would run out of space each month before we got fairly started.) Third, the tone of the review convinces me that these two new performances are in no way inferior to any of the others-which is not to say that the oldsters should be forcibly retired, only that they now exist in a new competitive context.

By the way, Curzon's deservedly popular London disc of the Quintet is being with drawn (it will reappear in the Stereo Treasury Series), but Clifford Curzon himself, bless his fingers, is not: he will be appearing in concert in the U.S. sometime next spring.

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

Jefferson Airplane

Congratulations to Josh Mills for his exquisite article on one of rock's all-time great ands, the Airplane. In an age when so many talentless bands are out to make a buck and hat only, it is encouraging to remember once gain the electric career of a group that cared bout its audience and what its songs were saying. Although we still have the Who, the Stones, and (stretching a point) Led Zep, the heart and soul of rock-and-roll has diminished. Reading about the Airplane did my heart and head good. It made me want to give my "Surrealistic Pillow" a few turns; although through years of listening it has acquired the "fireplace effect," the sound is still real and important.

MATT ROTS Bronx, N.Y.

Frank Sinatra

I wholeheartedly agree with Paulette Weiss ("The Pop Beat," October 1977) that he evening of July 16, 1977, was one of Frank Sinatra's finest hours. After seeing The Man n concert some sixteen times since his "re urn" in January 1974 at Caesar's Palace in Las Vegas, I must admit that he has some times been vocally rough (downright woeful).

At a concert in Pittsburgh last year he all but ruined the beautiful Embraceable You and turned his very own My Way into something best left unsung. But in recent months his, voice has seemed to be back in exquisite form, as at Forest Hills that horribly muggy July night and in two earlier engagements at he Latin Casino in Cherry Hill, New Jersey.

Just one small correction: the King opened the Forest Hills show with Cole Porter's Night and Day, not (as Ms. Weiss had it) I've Got You Under My Skin. And could you tell me why Reprise Records has put "Here's to the Ladies" on "indefinite hold"? What a bummer!

PAUL. M. MORK. Avoca, Pa.

The delay in releasing "Here's to the Ladies" has been caused by .the Boss himself. He was dissatisfied with several cuts on it and is re-recording some and scrapping others entirely. A Reprise spokesperson said simply, "When Frank says it's ready to go, we go." Opera Library

I enjoyed George Jellinek's "Essentials of an Opera Library" in the October issue, but I disagree with some of his choices. The best version of Tosca I have heard is the one conducted by Colin Davis for Philips. Herbert von Karajan is a great conductor, but I find his London version of Tosca lacking in drama-and it is a very dramatic opera-com pared with the one by Davis. With respect to French opera, I wonder if Mr. Jellinek is anti-Berlioz. There are two fantastic versions of Le Damnation de Faust available on discs, not to mention Davis' complete Les Troyens, which really brings the glories of the opera house into the home.

WILLIAM W. FIELD, JR. Tucson, Ariz.

Not anti-Berlioz-it's just that none of Berlioz's works are basic repertoire.The performance preferences listed by George Jellinek in his "Essentials of an Opera Library" I found, in the main, unexceptionable . . . except that one is struck immediately by the preponderance of all those "same old voices." I know that superstars sell records and that they all want to record their whole repertoire before they retire, but shouldn't we be getting just an occasional glimpse of the coming generation of singers anyway?

HERBERT KAUFFMAN, New York, N.Y.

The world's opera houses have been struggling with the question of retirement age for much longer than the U.S. Congress has. Unlike most employment situations, however, this one directly involves the wishes of the public as well as the employer (opera house or record company) and employee (singer). See this month's "Editorially Speaking" for more on the subject.

The photograph that accompanied George Jellinek's Essentials of an Opera Library in October caught my eye. Frank Dunand's pho to of Verdi's Otello at the Metropolitan Opera has done what would seem to me impossible.

When one studies the marvelous expressions on the faces of the singers and realizes that not one is obscured from view, it becomes apparent what a task this must have been. The amber overtones and costumes remind me of Rembrandt's famous painting The Night Watch.

HAL BROWN, Vancouver, Wash.

Who Writes the Songs?

I was so carried away by the charm of Barry Manilow's Mandy that by the time he worked his way up to I Write the Songs I was really impressed with his ability to write hit songs.

So I started buying his albums.

And reading the liner notes.

And he didn't.

Write the songs, I mean.

Well, okay, he writes the music for some of his songs, and an occasional lyric; but his skill seems to lie more in selection and arrangement. For the most part, his hits--like Mandy and Weekend in New England-have been written by other people. I was glad, though, to see the positive review of "Barry Manilow Live" (September), since he has considerable talent whether or not he writes the songs.

DONNA SELLERS, O'Fallon, MO.

Reel-to-reel Rawhide

I had just finished checking my oil wells on my ranch in my pickup truck when I read (October "Editorially Speaking") about this Tex as millionaire who tapes his direct-to-disc records. I fail to see how this is possible. Down here we use thin strips of rawhide for recording, not tape. Guess we're a mite behind you city fellers. By the way, my prescription-ground windshield got busted at the local honky tonk.

BILL PATRICK Pinehurst, Tex.

Barbra

In his October review of Barbra Streisand's album Superman, Peter Reilly states that Streisand picked up another Grammy for her song Evergreen from A Star Is Born. In fact, it was another Oscar. But my biggest gripe about this review is that Reilly falls in line with the rest of the country's critics who review Streisand the superstar and not the work she produces. Not once does he deal directly with what Streisand is doing with her voice these days, and, for all the article tells us, the album could have been recorded in Barbra's Jacuzzi with a cassette recorder. It's fine to reflect on an artist's professional motives, but when the reviewer neglects to re port whether Streisand sounds nasal, mellow, on key, or whatever, I think it is time to re evaluate his reason for being a critic.

GREG MITCHELL, Wichita, Kan.

Foster's Hits

In October's "Pop Rotogravure" Rick Mitz underestimates Bruce Foster's "Uncle Stephen" in saying that he "hasn't had a hit single in about one hundred and thirteen years." In 1940-1941, during a dispute be tween the broadcasting industry and ASCAP, several versions of Foster's Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair made the Hit Parade. It might be added that Nonesuch's two recent discs of Foster songs performed by DeGaetani, Guinn, and Kalish and the second volume in the Gregg Smith Singers' "America Sings" series for Vox constitute a welcome, if modest, step toward the "comeback" Mr. Mitz mentioned.

ROGER A. BULLARD, Wilson, N.C.

The Long View

Joel Vance's choice of 10cc's "Deceptive Bends" as a "Best of the Month" record for September strikes me as the most unfortunate mistake by one of your reviewers since Tina Turner's "Acid Queen" earned Peter Reilly's "BOM" nomination in January 1976. I think an important consideration in choosing records for this category-which often leads to a STEREO REVIEW "Best of the Year" award should be the music's ability to endure and delight for many years after the record's first appearance. Among the September choices Woody Herman, Wagner, and Arriaga probably qualify on this count; 10cc does not.

What is the "charm" in lines such as "Ah, you made me love you/Ah, you've got a way"? Lyrics like this are banal, moronic, and all but useless, regardless of their con text. I suggest that Mr. Vance take a refresher course in song lyrics. He might examine or re examine the words and their relation to the music in Jethro Tull's "Aqualung," Steely Dan's "Countdown to Ecstasy," or any of the later Beatles albums. These are records that have achieved permanence through quality. I very much doubt that "Deceptive Bends" will do the same.

CONRAD BAHLKE; Clinton, N.Y.

Well, check back in about twenty years.

Heart's Country

In his review of Heart's "Little Queen" in the September issue, Joel Vance said that the group is from Seattle, Washington. In 1976 Heart won a "Juno" award as the most up and-coming band in Canada. Heart is from Vancouver, British Columbia. Please don't try to steal our thunder.

IAN SAMS, London, Ontario

The Beatles Standard

If Alan Karpusiewicz (October "Letters") really wants to make a case against overpraising the Beatles, saying that the Searchers, the Hollies, and the Escorts (whoever they were) were better is idiotic. The Beatles may not have been the most technically proficient musicians around, but they were not sloppy.

Their greatness wasn't really related to this anyway. Their genius was to combine singing, songwriting, and playing with a certain indefinable special quality so as to create pure musical magic that has never been equaled by any other group. The Beatles will always be the standard for judging the accomplishments of any rock group. For what they accomplished and the joy that they provided in the very short period of time they were together, the Beatles can never be over-praised.

JON WOOLSEY, Fairfax, Va.

RFI

While I am glad the FCC is finally deciding the fate of quad-casting, I believe this is the wrong issue at this time. The FCC should now be devoting all its efforts to the problem of radio-frequency interference (RFI). Let quad casting wait; why take on new problems if you can't solve the old ones? I was the proud owner of a Fisher Model 634 quad receiver until it was besieged by the local CB operator-now I own a four-channel CB receiver! It is just one year old and it has visited the Fisher factory not once or twice but four times! It has spent more time there than at my house. Fisher went the full route installing capacitors, rewiring grounds, shielding antenna leads, and installing filters-before giving up. I installed and grounded shielded 18-gauge speaker leads and filtered the FM antenna. But I am still plagued by RFI.

Not about to give up, I took on the FCC.

Over the past year I have written twelve letters, but they have taken no action. The FCC seems to have an endless supply of Bulletin 25 (on RFI) and maybe they think it helps solve the problem, but believe me, it doesn't! I have heard that the FCC is understaffed and over worked, but isn't every federal agency? Every door of escape from the RFI problem has been shut in my face. Practical anti RFI measures have been taken with no results, I have been abandoned by the manufacturer of my equipment, and the FCC ignores me, so here I sit with the RFI problem smack in my lap! That is why I would like to see the FCC adopt a quad-casting standard-after the RFI problem is solved!

GLENN DRAKELEY, Clifton, N.J.

Technical Director, Larry Klein, responds:

Your experience confirms my statement made a year or so ago that the FCC is relatively in sensitive to the RFI problem, even if much audio equipment isn't. From your description of your troubles and your inability to effect a cure even with shielding, filtering, and modifications by the manufacturer, it seems likely to me that your "local CB operator" is using illegal amounts of transmitting power. That is the responsibility of the FCC! Do you have neighbors whose TV reception is troubled by the CB'er? Perhaps you can all get together to petition the FCC to send an investigator. (The FCC seems to respond more readily to com plaints of interference with television than with audio.) Have you checked the article on RFI in the May 1977 STEREO REVIEW? You may find some helpful anti-RFI techniques you have not yet tried. (Back issues are available from Ziff-Davis Service Division, 595 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10012. They cost $1.50 each post paid; payment must accompany the order.

CSN

When I first read Steve Simels' September article, "Regress Report on CSN . . and Y," I was furious. But I reread it several times and find that I agree--in part.

True, neither new album has the same position in my collection as the first CSN album or "Déjà Vu" by all four of them. But then the music doesn't have the same frame of reference; that is, it doesn't remind me of the same period of time. Seven years have come and gone-as have two Presidents, three Vice-Presidents, two national elections, and our involvement in Southeast Asia. The country has changed. It isn't that the music isn't good. It's just that it's different, and we all will look at it differently.

ROD REEVES; Orient, Iowa

If Los Angeles is "a living organism growing inexorably eastward," as Steve Simels calls it in his September review of new records by Neil Young and Crosby, Stills, and Nash, then it is only returning to its origin New York City, the source of everything cheap and vulgar in entertainment. It is also the source of the "music business" Simels derides because it no longer has a N.Y.C. zip code.

I haven't noticed any increase in vacuity or tastelessness in records made since the move to Los Angeles-since they could hardly get any worse! The record companies have al ways been noted for the very low percentage of excellent records they release.

SUE W. MOORE; San Jose, Calif.

Stereo Separation

I've been reading the letters STEREO RE VIEW has been publishing about disc quality and just have to add a complaint no one else has mentioned. I can tolerate pops, clicks and warps, but I can't tolerate there not being any separation in new records. There is getting to be less separation in stereo records now than when they cost a dollar extra, and as a result I'm buying more older records than new ones.

Why have expensive stereo equipment to play mono?

B.R. BILLINGS; Perrytown, Ark.

Have any other readers observed a falling off in stereo separation?

Jethro Tull

I was astonished at all the fallacies in Lester Bangs' review in the August issue of the Jethro Tull album, "Songs from the Wood." First, he did a critique of the group instead of the album. I would be the first to admit that this album is not the best of Jethro Tull's twelve releases, but it is obvious that Mr. Bangs does not like the group's style at all.

Second, he said that Ian Anderson once heard something of Roland Kirk's entitled Song for a Cuckoo. It was actually called Serenade to a Cuckoo. Third, he said that Anderson stole his entire flute style from that one song by Kirk. Poppycock. It was merely the first thing Anderson learned to play on the flute; he liked it so well that he put it on his first album for Chrysalis Records in 1968, with credit to Kirk. If a performer could steal another's style just by learning one of his songs, a lot more people would be buying the Beatles' song books.

CRAIG COLE; Garnett, Kan.

Lester Bangs' August review of Jethro Tull's "Songs from the Wood" was like a slap in the face. I generally don't pay much attention to what critics have to say (they are an insulting bunch, aren't they?), but when writers continually knock Ian Anderson it does make me a bit angry and even a little confused.

Since its beginning, Jethro Tull has produced good, quality material. Maybe the critics resent Anderson for moving Tull out of its original jazz/blues-influenced style into a more British one. Or maybe they're angry be cause someone as dull and boring as they say he is actually excites people. Whatever the reasons, Tull's critics are wasting their time on a lot of garbage when they could be listening to classics such as "Thick as a Brick," "Passion Play," or just about anything else Jethro Tull has produced.

KEITH BRODY; Miami, Fla.

STEREO REVIEW should help Lester Bangs find a new job.. His August review of Jethro Tull's "Songs from the Wood" proved his total incompetence as a record reviewer. As the not-so-proud owner of a copy of this album, I'll easily agree that it is below par. However, it is not reasonable to say, based on this one disc, that Jethro Tull's music has ". . . never been anything but ugly and trite." Mr. Bangs' characterization of the group's attitude as "up-tight, pretentious, and haughty" is a real example of the pot calling the kettle black. If he were not so busy impressing his very narrow attitudes on us, perhaps he'd have the time and the good judgment to re view the music on a record rather than the "pose" and "attitude" of the performers.

DON MERZ; Bridgeville, Pa.

Reading Binary

In "Audio's Digital Future" in the July is sue, the caption on page 83 gives as an example of a binary number and states it is.

to be read from left to right, "from least-significant to most-significant bit." Binary numbers are interpreted just the opposite; the left-most bit is the highest power of 2, hence it is the most significant.

JOHN.Q. DOOLAN; Arlington, Va.

Technical Editor Ralph Hodges replies: Digital numbers usually appear in print as Mr. Doolan describes. However, so far as we know there is no iron-clad convention for the sequencing of bits in audio-recording systems of the type discussed in the article. The flow of the diagram in which the number appeared was from left to right. Assuming that the most-significant bit would lead the data stream emerging from the recording system, we reasoned that it should take up the right-most position in the sequence, and the least-significant bit the left-most. We are sorry for any confusion, but we feel that the instructions given for interpreting the number were adequate.

Last Things

In his article "Making the Case for Elgar" (April 1977), Bernard Jacobson stated that in the end Elgar's religious faith turned to ashes and he refused the rites of the church on his deathbed. In his recent biography of the com poser in the Master Musicians Series, Ian Parrott comments on the matter as follows: "Since some doubt has been expressed on Elgar's faith at the end of his life, a letter from his daughter to the Musical Times of January 1969 needs quoting: 'Father Gibb, S.J. from St. George's, Worcester, was asked to attend, and to him my father re-affirmed his faith in the Roman Catholic Church.' Peter J. Pine, in a letter in the same issue, confirms this, adding the significant comment that 'Elgar would utter extravagant things under provocation or pain.' "

JAMES REIDY; St. Paul, Minn.

The Editor replies: Yes, and I recall my Irish grandmother commenting that we shouldn't be too hard on those who suffer a late access of piety, for it is simply unwise to take chances when it comes to our "latter end."

Audio Basics

MOVIE SOUND

LONG ago, in a movie studio far away, plans for a motion picture to be called Star Wars were beginning to take shape. History records that the studio moguls were not wholly optimistic about the economic possibilities of the film, but it was nevertheless decided to give it the full "wide-screen" treatment. This meant that it would be made available to exhibitors (read "theaters") suitably equipped to handle it as a 70-millimeter print with six-track sound recorded on four magnetized stripes running along either edge of the film.

The sound would be Dolbyized (the Dolby A process), and if they hadn't already acquired it, participating theaters could get the necessary Dolby equipment installed and gone over by Dolby technicians. The theater sound sys tem from projector to loudspeakers would also be checked out and equalized.

If you are one of the lucky few living within reach of perhaps ten to twenty theaters in the U.S. that have received this full treatment, you will have the chance to see and hear Star Wars-if you haven't already-in this rather impressive format. Unfortunately, most of the country will see the film as a 35-millimeter print and will hear it in glorious mono, the standard format of movie sound since the days of the Great Depression. But there is an intermediate possibility. The soundtrack on the 35-millimeter movie film is of course optical, meaning that it is a dynamic light pattern to which the film itself has been exposed, and it is intended to be played back by a light beam and photoelectric sensor within the projector. Actually, there are two optical tracks that the typical projector effectively mixes in much the same way as a mono cassette machine mixes both channels of a stereo cassette; the result is mono sound. However, the potential for at least two-channel stereo is certainly there, and some-by no means all-35-millimeter films have taken advantage of this.

Star Wars in fact goes a step further. Not only are the optical tracks of the 35-millimeter print Dolbyized; they are also encoded by the (are you ready for this?) Sansui QS four-channel matrix system. Mind you, this does not mean you'll necessarily get even a hint of this at your neighborhood theater. Just as anyone converting to multichannel sound must, the theater owner will have to invest in additional amplifiers and speakers to reproduce every thing that's on the "record." Many exhibitors refuse to, in which case they're free to go on playing the Star Wars soundtrack in mono for as long as they please. But a Dolby spokes man estimates that between one hundred and two hundred smaller movie houses screening the 35-millimeter print have gone along with the new system. This is significant when you consider the exceedingly plodding past progress of movie sound in its history of fifty years plus.

The Jazz Singer of 1927 is usually hailed as the first "talkie," but it didn't even have a soundtrack, unless you consider phonograph records synchronized with the film to be a soundtrack. Within a very short time the "Photophone" process-the archetypical optical soundtrack-took over completely.

Nothing much new happened for some time until 1940, when "Fantasound," the first multichannel movie sound process, was developed for and used exclusively by Walt Disney in his animated film Fantasia. There is some debate over what Fantasound actually was (it went through a number of evolutions), but it is clear that in its original form it used at least four optical tracks, one of which was a control track that regulated, from moment to moment, the assignment of different audio tracks to different speakers located throughout the theater.

We now skip twelve years to the three-projector "Cinerama" system, first of the highly publicized wide-screen processes. Cinerama's original soundtrack was on a separate 35-millimeter magnetic film synchronized with the picture, and it had seven tracks feeding five up-front loudspeakers and as many as eight speakers positioned around the sides and rear of the theater. A year later (1953) "Cinemascope" made its debut with four magnetic tracks applied to the image film it self. Track assignments were made in a way that has become something of a standard: the first three were left, center, and right, corresponding to appropriately placed loudspeakers behind the movie screen. The fourth, the "surround" track, fed speakers located here and there around the rest of the theater. Inaudible control signals recorded on the surround track along with the audio could switch the track on and off and assign it to different speakers. The apotheosis of the surround track is the curiosity known as "Perspecta Sound," in which a single (mono) signal can be switched by control tones to any of three loudspeakers.

With "Todd-AO" (1955), which employed a 70-millimeter projection print, the wide screen productions acquired the six magnetic tracks that are pretty much standard today. A move by Cinemascope the following year to seven tracks (increasing its film width to 55 millimeters in the bargain) tried to up the ante, but in time the industry lapsed back to six tracks. Today the standard formats are 70 millimeters and six magnetic tracks for wide screen presentations (including those modern films billed as Cinerama productions, such as 2001, Grand Prix, etc.), and 35 millimeters and two optical tracks (as often as not reproduced monophonically) for showing in smaller movie houses.

THE six magnetic tracks provide the film maker with plenty of flexibility. In Star Wars' case the track assignments are left, center, right, surround, and two remaining tracks for special low-frequency effects (the deep, seat-shaking roar of battle cruisers, for ex ample). When the 35-millimeter print is reproduced in QS, we get a left-front signal and a right-front signal, while a derived center-channel signal drives the center loudspeaker.

Rear-channel information derived from the QS decoder becomes the surround track, feeding speakers (when available) located at the sides and rear of the audience section. Reportedly, most of this is ambiance information, with only an occasional attempt at side or rear localization.

The evolution of movie sound, of course, is open-ended, and new developments may be in the works. By the time the next installment of Star Wars reaches your local movie screen, some additional sound barrier may have been broken to give audiophiles in the audience a new thrill.

Installation of the Month

By Richard Sarbin

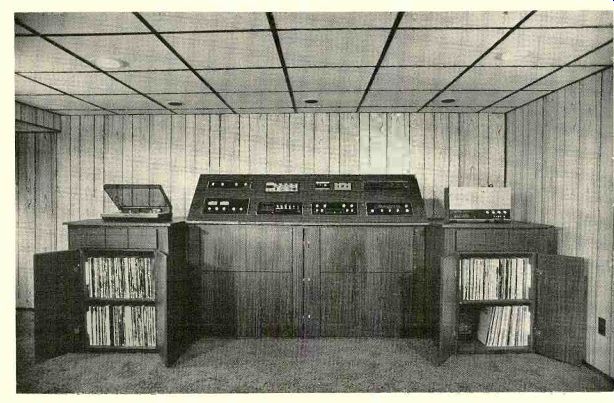

MOVING to a new home in Lansing, Michigan, gave audiophile Karl Weathers the necessary motivation to get down, finally, to constructing this rugged and efficient audio installation. Working from a design in an 8:1 scale balsa-wood model, Mr. Weathers built the one-piece, slant-top console in a week's time using 3/4-inch plywood over a frame of two-by-fours.

All exterior surfaces are covered in rosewood-grain Formica to provide an attractive finish and protection against possible heat or water damage.

Nine rectangular cutouts in the central equipment section accommodate the basic system. The all-McIntosh lineup in the bottom row includes (left to right) an MC 2105 power amplifier, an MPI 4 performance indicator, a C 28 preamplifier, and an MR 74 tuner. In the top row are (left to right) a McIntosh MQ 101 equalizer, a Heath IG-18 sine-wave test generator, a dbx 119 dynamic-range enhancer, a switch panel (to control lighting, speaker-system selection, and reverb level), and a Panasonic eight-track cartridge deck. To maintain proper cooling, the cabinet is vented with 4-inch-square screens at each end while an exhaust fan positioned above the power amplifier draws a steady flow of air over the equipment.

The recessed center and the angled top of the main housing were designed to create a space-age look and offer the system's "navigator" sufficient room in which to operate his program sources. Its ample interior pro vides easy access to all the equipment for repair or system-rewiring projects.

RESTING on the tops of the left and right storage cabinets are a B&O 4001 radial-arm turntable with B&O cartridge and a Nakamichi 700 cassette deck. Below each of these units are drawers containing both cassettes and eight-track cartridges as well as equipment-maintenance materials. Lights built into the side walls of the record cabinets illuminate the titles of Mr. Weathers' collection of rock, classical, and easy-listening discs. The doors to both side cabinets and the central housing unit are equipped with spring-loaded hinges and are therefore self-closing.

Two ESS amt-3 speakers positioned directly across the room from the equipment complex serve as the main (front) speakers for the system. A pair of smaller Genesis II bookshelf speakers mounted in the left and right walls face each other at ninety-degree angles to the main speakers. A synthesized "ambiance" rear channel based on the difference signal between the right and left front channels is achieved by connecting the positive leads of each bookshelf speaker to the amplifier and the negative terminals of each speaker to each other.

Mr. Weathers, a purchasing agent with Delta Dental Plan of Michigan, reports that the basement of his new home was specially designed to accommodate the sizable audio console and to serve as an acoustically correct listening environment. Although satisfied with the overall performance of his sys tem, he is preparing to upgrade it with a McIntosh' MC 2205, which has twice the power output of his current amplifier.

Technical Talk

By Julian D. Hirsch

PHONO-CARTRIDGE LOADING: Over the years I have written several articles dealing with the problems that arise at the inter face between the preamplifier and the cartridge (including one way back in February 1972 on the little-appreciated effects of pho no-cartridge inductance on high-frequency performance), but the matter has continued to be neglected by many preamp designers and testing laboratories. In recent months, how ever, the effect of the load impedance on the frequency response of a magnetic phono cartridge has been receiving some long-overdue attention in the audio press, and capacitive/ resistive cartridge-load adjustments are showing up regularly in the latest equipment.

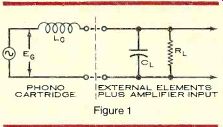

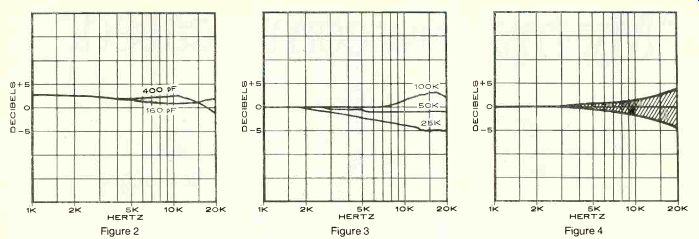

To appreciate why the load (the capacitance and resistance seen by the cartridge be fore-and at-the preamplifier's phono input) can have such a strong effect on conventional magnetic cartridges (moving-coil cartridges and those not based on magnetic principles are relatively immune to such effects), it is necessary to understand the electrical equivalent circuit of a magnetic cartridge. This is shown in Figure I, greatly simplified by the omission of the cartridge's internal resistance and stray capacitances.

In this circuit, the voltage EG, generated by the cartridge as a result of stylus motion, is assumed to be a faithful replica of the record ed program waveform. At some frequency, usually in the highest audible octave or even at an ultrasonic frequency, the coil inductance Lc will resonate electrically with the total circuit capacitance CL. This causes a frequency-response peak at the resonance frequency. The amplitude of this peak is reduced by the load resistance RL. If this resistance is made small enough, there will be no output rise at all, but rather a steady decrease in out put as the frequency increases.

As a rule, the cartridge's electrical resonance is used to compensate for other response aberrations arising from the mechanical operation of the system. A real stylus and generating system will usually have its own mechanical resonance, between 15,000 and 25,000 Hz, which can affect the tracking ability as well as the frequency response of the cartridge if it is not controlled. Some form of mechanical damping is normally applied with in the cartridge structure to reduce the effect of the stylus resonance. This also tends to reduce the high-frequency output, just as a heavily damped electrical circuit does.

Figure 1

By locating the electrical resonance peak at the correct frequency in relation to the mechanical resonance, and by adjusting the amplitude properly, the cartridge designer can compensate for much of the mechanical high-frequency loss by using the boost from the electrical resonance. If all goes well, the result is a flat response through the audio range.

To ensure the correct frequency and amplitude for the electrical resonance, the cartridge designer must specify the proper resistance and capacitance loads. In most cases, the resistance is the now-standard 47,000 ohms (nominally 50,000 ohms) used in all phono preamplifier input stages (100,000 ohms for CD-4 cartridges). The capacitance is much more difficult to predict, however, owing to variations in the length and type of shielded cable connecting the record player to the amplifier and similar differences in the wiring within the tone arm. In addition, the capacitance of the input circuits of phono preamplifiers is far from standardized and can be almost anything from nearly zero to hundreds of picofarads (pF).

A typical stereo cartridge is designed to operate with a capacitive load of 250 to 300 pF.

This matches fairly well the actual situation existing in a hi-fi installation. Fortunately, the exact capacitance is not very critical. Some manufacturers, notably Shure and Ortofon in their non-moving-coil models, design their cartridges for flattest response when loaded by 400 to 500 pF, and many music systems will require the addition of external capacitors to achieve these values.

What is the actual result of a load-capacitance mismatch? The effect depends to a great extent on the inductance of the cartridge's coils as well as other characteristics. A low inductance implies less dependence on critical loading for a correct frequency response (un fortunately, it also implies a lower output voltage, all else being equal). We made frequency-response measurements on a cartridge having the moderately low inductance of 580 millihenries and whose specifications are based on a 275-pF capacitive load in parallel with 47,000 ohms. The results of changing the total capacitance from 160 to 400 pF, with the resistance maintained at 50,000 ohms, are shown in Figure 2.

The effect of the capacitance change, though hardly of major magnitude, might change the sound of the cartridge enough to influence some people's choice, and it might easily be overlooked by many others. The correct load of 275 pF gave a response curve essentially identical to the one shown for 160 pF. Notice that a higher load capacitance does not reduce the apparent high-frequency response of the cartridge. Quite the contrary:

it gives about 2 dB more output in the most audible part of the high-frequency range, and on many systems will make most records sound brighter, more "open," more "de tailed," and so forth. The output loss above 15,000 Hz is much less likely to be audible.

When we fixed the capacitance at 250 pF and varied the resistance termination from 25,000 ohms to 100,000 ohms, the effects were much more pronounced. Figure 3 shows the impressively flat response obtained with the rated load of 50,000 ohms. Despite its specification, the actual input resistance of an amplifier may differ somewhat from the nominal 47,000 ohms. According to the results of a survey of twenty-six different phono preamplifiers printed in the Boston Audio Society's Speaker in April 1977, input resistances fell between 35,000 and 60,000 ohms.

Judging from the curves we measured at 100,000 and 25,000 ohms on this cartridge (it is quite typical in its reaction to load changes), audible response might be affected materially by the choice of amplifier.

Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4

There is yet another effect to be considered. The cartridge's coil inductance can interact with the RIAA equalization circuits of some preamplifiers in such a way as to alter the internal equalization accuracy of the amplifier. The curves in Figure 4 show the typical range of variation we have found in a number of preamplifiers when the measurement is made through the coil of a phono cartridge. This change should be added to what ever curves result from the specific resistive and capacitive loads to obtain the net response of the cartridge/amplifier system. (In each case it is assumed that the cartridge and amplifier, in themselves, have a perfectly flat frequency response curve when measured separately.) Note that these changes can improve the sound in many cases by bringing a system's overall response closer to flat. And although only the frequency response is affected by the interface mismatch, many subjective effects (openness, nasality, harshness, etc.) resulting from frequency-response aberrations are charged against other, sometimes mystical, factors. I would suggest therefore that many-if not most-of the apparent differences between cartridges and/or phono preamplifiers are really the result of these and similar random interface problems. No won der there is so much disagreement as to the specific, or comparative, sound properties of these components! A final note: there are other cartridge properties, such as distortion and channel separation, that have not been covered in this discussion because they are determined largely by the design of the cartridge and are affected only slightly, if at all, by external electrical load conditions.

The Pop Beat

DISCOMANIA

THE hottest item at a rock-'n'-roll convention in New York City several months ago was a tee-shirt bearing an extremely obscene comment on disco. Most rockers just don't take kindly to disco music. They act as though its very existence were a personal affront, and they tell whoever will listen that it is soulless, mechanical, and likely to cause softening of the brain. One frustrated rocker known only as La Lumia has actually organized a nation wide movement called "Death to Disco." He provides buttons and bumper stickers bearing the grisly slogan, plus a manifesto stating his creed. (If you're interested, Mr. La Lumia is available for lectures and rallies.) And it's not just the rockers who have gone off the deep end on the subject of disco. Jazz purists, too, complain that disco is not only a cheap form of music, but that it has robbed them of fine musicians who have "sold out" their art in crossing over to the greener pastures of commercial success it offers. The complaints come fast and furious: disco wipes out an artist's individuality, mashing his efforts into the pulp of its monotonous sound; disco is fickle and trendy-last night's hot platter is tonight's cold potato; and so on.

Even though it may be true up to a point, complaining is as futile as shaking your fist at a hurricane. Disco is an outgrowth of the times, which are confusing, often depressing, and not likely to change quickly. What disco provides is a little vacation from all that-and it's fun. It tends to be mindless fun, but there in lies its appeal. Its emphasis is on the feet, not the head, and dancing to it is an escape from the heavy burdens of both the day and the decade. Discotheques are glittering little fantasy worlds where elaborate lights and hypnotic music conspire to make every patron the star of his own romantic scenario for a night.

Disco does have its virtues. It has provided a shot of vitamin B12 to the careers of both new and established artists and to a number of small record companies. It has rejuvenated the night life of urban centers, boosted the fashion industry, added a little spice of glamour in places where there was none before, given many their only form of exercise, and probably trebled the income of Arthur Mur ray Dance Studios throughout the land.

Yes, some jazz artists have sold out for commercial success (hardly a new phenomenon, by the way). But some have simply temporarily gone after the rewards that, sadly, artistic integrity never brought them. Take the case of jazz keyboardist Herbie Hancock, who was ripped into by jazz critics in 1973 for his first patently commercial (and enormously popular) album, "Headhunters." This year he had money in his pockets and the grin of a satisfied man on his face when the same critics who had mourned his loss to jazz were bowled over by his latest release, "VSOP." Disco has resurrected and similarly reward ed neglected r-&-b performers like Thelma Houston and Loleatta Holloway, who have returned the favor by breathing life into its of ten rigid form. Unfortunately, solo artists whose fame rests solely on disco tend to disappear in the overall crush of heavy orchestration favored by most disco producers. The vocals of Carol Douglas, Silver Convention, and the relentlessly loving Barry White, for instance, are reduced to premeasured structural blocks slipped into premeasured holes in assembly-line songs. Occasionally a Vicki Sue Robinson or a Savannah Band will appear with the ability to soar above the formula, but they are the exceptions.

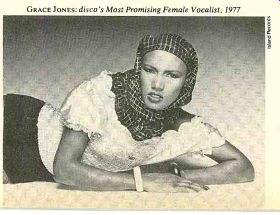

------ GRACE JONES: disco's Most Promising Female Vocalist, 1977

But whether disco music makes your feet tap or your flesh crawl, it's here to stay for a while. As an industry, it grosses four to five billion dollars annually, second only to organized sports in the entertainment field. There are over 11,000 discotheques in the U.S., nearly 1,500 in Europe, and even the Soviet Union, at last report, sports a pair. Thirty-five percent of the records currently sold in the U.S. are disco oriented, thirty million people listen to them, and approximately fourteen million dancers flock to discotheques every week.

FOR four days in September, Disco HI, a forum sponsored by the music trade magazine Billboard, brought home the growing clout disco has in all areas of the entertainment business. The panel discussions and exhibits left the impression of a young and booming industry delighted with its success and groping for a formula to insure it. Artists, producers, record-company representatives, club owners, disc jockeys, and equipment manufacturers participated, and some of the news they imparted was pretty impressive.

If you thought disco was just an urban phenomenon, think again. Mobile discos have been bringing joy to hundreds of pairs of sub urban and rural feet. The mobile units are equipped with sound systems, portable lighting equipment, and sometimes even with port able dance floors and smoke machines. Usually rented by schools, charitable organizations, and such, the units can set up a functional, parking-lot disco in nothing flat.

The exhibit areas at Disco III featured other eye-opening developments. Many clubs employ the very latest in modern electronics, and the advanced sound systems, the astonishing array of lighting equipment, and the matter-of-fact use of holography, lasers, and large-screen TV projections were all but mind-boggling.

Top disco acts (Gloria Gaynor, Tavares, and the SalSoul Orchestra, among others) provided entertainment each evening, and the four-day affair culminated in an awards dinner as boringly predictable as any tedious organizational function you can imagine. One high point (if one can call it that) of the awards ceremony was singer Grace Jones' acceptance of the Most Promising Female Vocalist plaque while her purse was being stolen from her seat on the dais six feet from where she stood. The incontestable low point was the seemingly endless parade of disc jockeys accepting awards (there must have been at least one platter handler from each state in the union).

IN short, disco is not about to go away, so you might as well give in, dress up, and accept Irving Berlin's invitation to "face the music and dance." Who knows-you might just get to like it.

Going on Record

FROM SWEDEN WITH LOVE

Is past summer, in conjunction with Sweden's challenge for the America's Cup and under the patronage of the royal family, the Swedes decided to send us, on loan, their Michelangelo Pieta, their Scythian gold, their Mona Lisa, their Laurence Olivier, their Noel Coward, their Edith Piaf, , their Dylan Thomas, and their Bob Dylan. He arrived in July to begin a brief tour, five concerts of "A Swedish Musical Odyssey" in Newport, Rhode Island, Saratoga Springs, Washington, D.C., New York, and Detroit. He is Sven Bertil Taube, actor, singer, reciter, and balla deer, and as charming a personality as ever graced a concert stage.

To say that Taube is one of the premier entertainers of the world is only to state what is obvious after seeing and hearing him. If he is not yet a household word throughout the western world, it is only because not every one has yet seen and heard him. He is the latest in a long series of fine Swedish exports:

Jenny Lind, Ingrid Bergman, Jussi Bjoerling, Carl Milles, Birgit Nilsson, Ingmar Bergman, Bjorn Borg. If he has been slower in coming to us, it may just be because the Swedes have held on to him more tightly. Certainly, they have bought more of his records than those of any other musical artist, classical or popular, including the Beatles. But Taube has now stepped upon a wider stage; what he does is international.

To explain precisely who and what Taube (pronounced "tohb") is, and what he represents, is a complex task. "I come from a tradition," he has said-meaning one specific thing, the balladeer, but unintentionally implying a whole range of possibilities. Certainly, he is the embodiment of traditions, many of them. He is the son of Evert Taube, the late composer of ballads that are so revered in Sweden they seem to have become, at the very moment of their creation, an integral part of the history of Swedish culture. Evert Taube himself was in the tradition of that fascinating eighteenth-century poet and troubadour Carl Michael Bellman, whose songs the perfect aural equivalent of the prints and water-color paintings of the great Thomas Rowlandson-give us a living portrait of the low life of an age. Sven-Bertil Taube has for years been the outstanding interpreter not only of Bellman's work but of his father's as well.

BUT Taube is not just a singer; he is an actor with the most sensuous of feelings for the sounds of words. His singing voice is an at tractive but relatively ordinary instrument, but his speaking voice is altogether extraordinary. Capable, through pitch, inflection, and language, of delineating half a dozen different characters in the space of a minute (a task he performs in Bellman's Fredman's Epistle No. 33), it is a real virtuoso instrument. And he drops into a new language in somewhat the

------- Swedish balladeer Sven-Bertil Taube and conductor Ulf Bjorlin

same way a jazz musician drops into a new rhythmic groove.

Taube was a leading actor with the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm, under the direction of Ingmar Bergman, for ten years. He has made films and television appearances in England as well as in Scandinavia. He has given concert performances in many places in Europe. In New York he appeared with the American Symphony Orchestra, conducted by his friend and associate Ulf Bjorlin, an excellent musician who frequently guest-con ducts the Stockholm Philharmonic and who has a recorded discography of over two dozen discs, from Johann Helmich Roman to Webern. The orchestral part of the program comprised Handel, Blomdahl, Ibert, and Wagner; Taube sang (with the full orchestra) and recited Bellman and Evert Taube, plus poems by the Nobel prize-winning Harry Martinson which were interspersed with sea chanties.

The orchestra played as well as I have ever heard it; Bjorlin's arrangements were altogether splendid; and Taube himself was completely winning.

Just to watch him on stage is an object les son in what to do with your hands while per forming, and his wordless interpretation of an orchestral postlude-standing, one hand in his pocket, his back three quarters to the audience, seeming to gaze at some far-distant scene located about ten feet up on the rear wall of the stage-had the audience "seeing" pictures that were not physically there. The vigor of his songs-with elegant articulation in English (a trace of Winston Churchill in the sound), French, Swedish, high and low Ger man, and Spanish-wonderful waltzes, marches, dramatic ballads, chanties, and all was completely captivating. Through every thing came the feeling of a real and unique personality--rooted in historical tradition, yes, but very much a contemporary--who can play at will with the space created by an intimate performing medium and a large orchestra, hall, and audience.

ARRANGED to have lunch with Taube the following week. I was delighted that he brought with him his latest recording (HMV England 862-35135), but somewhat nonplussed when it turned out to be songs of the Greek political writer Mikis Theodorakis, which Taube sang in English accompanied by a guitar consort and a bouzouki. I confess that when I heard it I understood for the first time (no printed lyrics were necessary) just what those songs were all about-the irony of bitter lyrics coupled with infectious music. It was fascinating to match that with Taube's admitted major concern: he did not want the songs he sang, whatever their origin, to be less in English than they were in their native tongues.

Taube has made over a dozen records, mostly in Swedish and mostly for the Swedish HMV label (EMI Svenska). While more than half of them were at one time imported, they do not seem to be so today. Obviously, that situation will soon be remedied as Taube's star rises. There is, at present, one record on the domestic Fiesta label (Fiesta 1589) on which he performs music of his father. The Theodorakis record will certainly find its way into stores that do direct importing, 'and it may yet be released over here. And the "Swedish Musical Odyssey" concert has been recorded and released in England and is under consideration for American release.

Most important, Taube himself will be back in person. Watch for him.

++++++++++++++

Also see:

A BEGINNER'S GUIDE TO HI-FI---Selecting equipment intelligently is something anyone can do ROBERT N. GREENE

Technical Talk, Julian D. Hirsch

I Remember Mono--An Audiobiography

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)