CASSETTE DECKS -- A look at the specs and features available in each price class

-- --Superscope CO-303,$135; Sanyo RD4550, $100; Sankyo STD-1700, $150

Once you know what technical specifications and operating features are available within each price class, half the buying job is over.

By Ivan Berger

--Uher CG-362, $945

ONCE you've decided that a cassette deck is what you want to buy, the easy part is over. What you have to do now is buckle down and study the features and specifications of all the available units and figure out what they mean in terms of your personal performance needs. And once you've done that, you need to deter mine which of those operating features and technical specifications are avail able in each price range and try to arrive at a relatively painless compromise (if compromise you must) between the performance you want and the price you can pay.

If all that sounds a bit too much like work, rest easy: we have already done much of the required research and are about to offer you a series of synopses of what is available in each price class.

When you know just what you get-or don't get-at a given price, you'll be able to decide whether it would be better to pay a little more and step up a notch or two, or to lower your sights a bit and perhaps spend the difference on tapes or microphones.

Under $160 Cassette decks bearing price tags of $160 and under tend to have few special features and to be somewhat skimpy in technical performance as well. You can usually expect wow and flutter figures (weighted) of about 0.1 to 0.25 per cent. This is good enough to keep the music from wavering or gargling audibly-unless you are particularly sensitive to such effects. Listen to a recording of a piano, harp, or acoustic guitar on the unit to determine if the wow and flutter is low enough for your ears. Dolby noise reduction is fairly standard even at these prices-but even with Dolby noise reduction, neither frequency response (typically specified at about 50 to 13,000 Hz, with no statement as to flatness) nor signal to-noise ratio (about 55 dB with Dolby) is equal to that provided by the better FM tuners. What that means in practice is that if you compare your recordings directly with the FM broadcasts or records you tape, you'll hear a notice able (though not always very notice able) difference. But, in any case, most listeners find the performance at this price level perfectly acceptable.

You will find a few extras, even here, if you look around a bit. Servomotor speed control is fairly common, and several models have a peak-limiter switch. (Limiters let you record at a higher average level without worrying that sudden transient peaks will over load the tape or heads and cause distortion. Since the higher noise levels of low-cost decks force you to record at higher average levels, such a feature can be quite useful.) At the very bottom of this price range, Lafayette's $70 RK-715 omits even microphone inputs-but that's not as serious as it appears. Many users of even more expensive decks seldom make live recordings, but just tape off the air, from records, or from other tape decks. Advent, in fact, omits mike inputs from its $400 201A deck for just that reason (though low-noise micro phone preamplifiers are available for it separately, at $40, if you need them).

Around $200 At this level, ±$25 or so, you'll find both improved performance and a few more features. In addition to peak limiters (or in place of them) there will of ten be peak-level indicators that flash to indicate the presence in the recording signal of high-level transients that are too fast for the recording-level meters (which read average, not peak, signal levels) to catch but which are still capable of overloading the tape momentarily. Peak-level indicator lights can also be monitored visually from across the room while you are taping a broadcast.

Adjustments for tape type get more flexible in this price range also. While simpler machines tend to have single switches which change bias and equalization together to match either of two general tape formulations, more expensive models offer at least three or four combinations, usually by separating the bias and equalization switches.

Sansui SC-5100, $600; Teac A-640, $550; Hitachi D-220, $160 Fisher CD 4020,

$170

Royal Sound RS-5800, $500 Dual C919, $450; Realistic SCT-15, $200 Kenwood KX-620, $220; Yamaha TC-511S, $260; Optonica RT-2050, $300; Hitachi D-800, 5400

This increases your chances of matching the characteristics of the deck accurately to the tape you're recording with. Several machines have memory rewind, a convenient aid in checking back on what you've just recorded: set the counter to zero when you start re cording, and when you've finished, press the rewind button; the tape will return to the zero point and stop itself, ready to replay. Cueing is another handy feature to have; it lets you monitor the "chatter" of the tape in fast forward or rewind for fast location of se lections. Several decks have input mixing too. With line and microphone-input circuits separately controlled, you can use both at once, mixing live material from your microphones with music or sound effects from records.

You can sing along with the Met (or the Muppets) or add a little prerecorded color to a taped bedtime story or slide narration. Independent output-level controls also begin to appear in this price class.

The chief differences between this price class and the one below it are in the area where improvement is most needed: performance. 'The typical deck in the $200 class has a signal-to-noise ratio (with Dolby) of 60 dB or better about what you'll get from most FM tuners on stereo programs--and response that's flat within ±3 dB to 13,000 Hz or so. Wow and flutter specs also improve significantly, to between 0.08 and 0.1 per cent, typically, in a weighted measurement. That's not terribly impressive by the standards of the best cassette machines (though open-reel machines, not too long ago, couldn't have matched this performance at this price level). But the ratio of price to performance is attractive enough to make this a very popular price category.

Around $300 The range here is actually from about $235 to $340, and it offers the widest model choice-about fifty-though only about twenty manufacturers are involved. The main improvement in performance here is in high-frequency response, which is typically flat within ±3 dB to 16,000 Hz-or at least to 15,000 Hz. Add a slight improvement in signal-to-noise ratio (just a decibel or two, on the average) and another slight improvement in speed constancy (wow and flutter averaging about 0.06 to 0.09 per cent instead of 0.08 to 0.1), and you'll get sound that's on a par with that of a good FM tuner receiving a strong stereo signal, but still not quite a match for that of a top-quality, widerange disc.

One indication of the performance available is the profusion of switchable multiplex (MPX) filters (they are almost unknown on lesser decks). Since the 19-kHz "pilot" tone that is a necessary but non-audible part of stereo FM signals can confuse Dolby circuits, and since not all tuner filters adequately suppress this tone, most cassette decks have circuits to filter it from the signals they're recording. But such filters also tend to reduce high frequencies down around 15,000 Hz, so it's good to be able to switch out that filter when you don't need its services. And if the deck's high-frequency response is capable of approaching 19,000 Hz, switching out the filter becomes more and more important if the recorder's full potential is to be realized.

" ... they seem to evoke an acquisitive itch ... "

Two other features commonly found in these decks are also FM-oriented. A Dolby-FM switch position enables you to use the deck's Dolby-decoder circuitry as a "straight-through" decoder for Dolbyized FM broadcasts you don't wish to record. The other FM-oriented feature is timer record.

Together with a suitable external timer--anything from an appliance--switching clock to Nakamichi's elaborate digital device-this feature lets you set the deck to start recording at a preset hour-handy if there's a pro gram you want to tape while you're not home.

The $400 Class ( ±-$50)

Here is where luxury begins. Performance in all categories improves slightly, with rated frequency response often running to 17,000 Hz or more within ±3-dB limits and wow and flutter often as low as 0.05 or 0.06 percent.

But the most obvious differences are in the operating features offered (major improvements over the performance level of the $300-class machines would be very difficult and even more expensive to attain).

Below this price level there are very few three-head decks (Fisher has one for as little as $250), but in this class there are several. With separate heads for erase, record, and playback (in stead of one head that must serve for playback and recording alternately), you can monitor your recordings as you make them, listening to the output from the playback head while the re cording is still in progress. Each head can also be designed to do its job with out the technical compromises inherent in dual-purpose heads: the record head's gap can be made wide to resist saturation and consequent distortion, while the playback head's gap can be made narrower for more extended high-frequency response.

You'll also find a few more decks with multiple motors. Their servomotors drive only their capstans, and a second motor drives the take-up and supply hubs. That opens up the possibility of reduced wow and flutter (which greatly depends on the capstan's steadiness of motion) and of faster rewind and fast-forward operation (for a C-60 tape, typically 1 minute with two-motor decks, 1 1/2 minutes with one-motor models). It also simplifies the tape-transport mechanism, which should make for greater long-term reliability.

Recording-bias frequencies are higher in this class, typically 95 to 105 kHz rather than the 85 to 95 kHz of $300-class machines. That also helps high-frequency performance; the de sign rule-of-thumb is that the bias frequency should be five times the highest frequency to be recorded to prevent mutual interference.

One of the main limiting factors in cassette recording is the tape itself.

Tape manufacturers therefore keep coming up with improved formulations. But these often have slightly different bias-current and equalization requirements than existing tapes. To take full advantage of these new formulations (including those yet to be developed), most of the more expensive decks have, at a minimum, separate bias and equalization switches, often with three positions each instead of the two apiece more common in the previous price group. (Three settings per switch doesn't always mean nine possible bias/equalization combinations, however; equalization is often the same in two positions of that switch, with the extra position just to provide a visual match for the three distinct positions of the bias switch.)

JVC's KD-75, Aiwa's AD-6400 and AD-6550, and Kenwood's KX-1030 also offer fine adjustment of bias or equalization (JVC's knob is a five-position switch while the others are continuously variable over a range of about-2:10 percent). Several decks can also sense mechanically when physically coded chromium-dioxide cassettes--or their electrical equivalents-are being used and set their own bias and equalization accordingly.

----------------------

GLOSSARY OF CASSETTE-DECK FEATURES

Automatic CrO2 switching: A mechanism in a cassette deck that automatically switches the machine's bias and equalization when it senses the presence of a coded notch in the rear edge of a chromium-dioxide cassette.

Automatic reverse: An operating feature that enables a cassette deck to play-and sometimes to record-in either direction of tape travel.

DIN jack: A jack designed to accept the European-type plugs that consolidate the four tape inputs and outputs into one socket (four "hot" leads plus ground).

Dolby: The registered trademark of a noise-reduction system developed by Dolby Labs, Inc. Most cassette decks include a Dolby-B circuit which reduces noise introduced in the process of making a recording but is not designed to do anything about noise already in the program being re corded, whether it is an FM broadcast or a disc.

Input mixing: Facilities permitting the combination (mixing) of several inputs (microphone or line) on the limited number of available "tracks" of a tape recorder (two in the case of a cassette deck). On cassette decks, this facility is used for mixing the line inputs (from a disc or tuner source) with one or two microphone inputs.

Limiter: A circuit that restricts input signals to a certain maximum level near the approximate overload point of the tape. This prevents overload and saturation of the tape by large in put signals while allowing recordings to be made at a high enough level that tape noise is not excessive.

Memory: A feature that simplifies finding the beginning of a specific recording. To use the device, the tape counter is set to "0" at the start of a recording; later, the memory feature will return the tape to the exact point at which the recording began simply by placing the deck in the rewind mode.

MPX switch: A front-panel switch that inserts a multiplex filter into the input-signal path for recording stereo-FM broadcasts. These broadcasts are accompanied by a 19-kHz pilot signal which, though beyond the frequency range of just about all cassette decks, could result in audible "beat tones" if it were to interact with the bias signal of the tape deck.

A more common problem arises from the fact that the Dolby encoding circuit can be confused by the 19-kHz signal and respond improperly. The MPX filter applies additional suppression to the 19-kHz tone (in addition to that already applied by the FM tuner).

Multi-motor deck: A cassette machine with separate motors to drive the capstan and the tape hubs. Decks are available with two and even three motors.

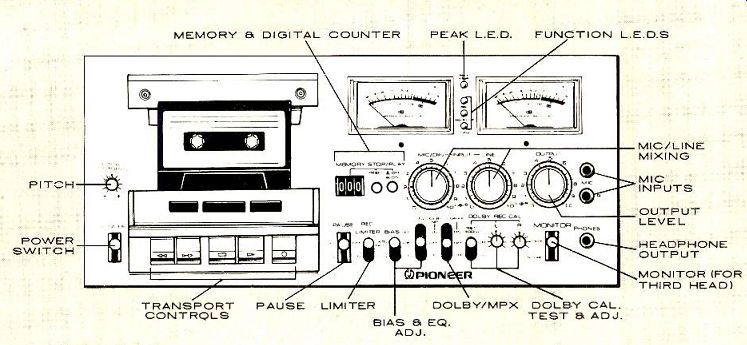

Peak LED (light-emitting diode): A flashing indicator of transient high level input signals that exceed a given preset threshold level that approaches overload.

Peak-reading meters: Meters that have electronic assistance circuits enabling them to indicate instantaneous peak values of the input signal.

They indicate fast high-frequency signal peaks that average-reading (or VU) meters barely respond to.

Pitch control: A knob that permits variation of a cassette deck's nominal tape speed over a small range. This feature can be helpful to a musician wishing to alter the pitch of a recorded composition slightly in order to play along with it.

Servomotor: A (usually) d.c. motor whose rotational speed can be con trolled by speed-detection circuitry that generates an error-correcting voltage whenever the motor's speed drifts from its proper value.

Solenoid operation: In place of mechanical linkages to control the tape transport, some cassette decks have light-touch pushbuttons. These switches apply current to a solenoid (an electromagnetic mechanism), and the solenoid does the actual work of resetting the internal drive mechanisms for the desired operation.

Three-head deck: A cassette machine with separate erase, record, and play back heads that permit monitoring off the tape as a recording is being made. (A few machines have a non-monitoring third head for tape calibration.)

Timer: A switch or switch position that allows the deck to start recording the moment a.c. line power is applied to it. If the a.c. power is controlled by an external clock timer, unattended recordings can be made.

Variable bias/equalization: Controls (either multiposition switches or potentiometers) which afford greater-than-average flexibility in setting bias and/or equalization to achieve the best performance from a particular tape type.

----------------------------------------

Interesting and individual features begin to crop up more frequently in this price class. The Advent deck has just one meter instead of the usual two. The single meter can be switched to monitor both channels at once (showing the higher level of the two) or to show the level in either channel. Along with the master level meter goes a master level control with individual adjustments for each channel for level matching (the Marantz 5030 and Rotel RD-30F share this latter feature). Two of Aiwa's models can be started and stopped automatically by the Aiwa turntable to simplify the taping of discs. Marantz's 5420 and 5400 have pan pots in their in put mixers so that some signals to be recorded can be positioned at any left-to-right point within the stereo spread, and Nakamichi's 500 has a third "center-blend" microphone input. Sansui's SC-3100 will automatically skip the initial portion of the tape to guard against your trying to record on the nonmagnetic leader. Dual's C919 can be in stalled as a top-load or front-load unit, with pop-up meters and small mirrors over the tape compartment so that the meters and tape motion will be visible from whatever angle you view the deck. Sharp's RT-3388 has a built-in microprocessor (a true computer) to control everything from timing recordings to finding any particular selection on the tape at the press of a button.

Above $500

This is where the decks become so feature-laden and attractively styled that they seem to evoke an acquisitive itch automatically. These are, of course, the models that are least alike in appearance and facilities, because price no longer restricts the designer's expression of individuality. Virtually every feature mentioned so far can be taken for granted here. There's hardly a deck lacking three heads, mixing in puts, memory rewind, timer start, high bias frequency, and so on. Quite a number have multiple motors as well, and several three-head machines employ dual capstans, one on either side of the head assembly, to regulate tape tension across the heads and smooth tape-speed irregularities. And though overall performance is better than that of the $400-class machines, again it's just a little better: yet another kilohertz or so at the high end, signal-to-noise ratios more frequently above the 60-dB mark (and here and there above 70 dB), and perhaps another 0.01 per cent knocked off the wow and flutter figure.

The one specification that shows most improvement is fast-winding time (owing to the multiple motors).

Many of these deluxe models are solenoid-operated, with very light-touch pushbutton controls. Solenoid operation makes it easy to add remote control as an extra-cost option. Remote control makes it easier to cut out commercials and announcements from your armchair when you're taping off the air, or, with the controls by the turntable, to start and stop a recording more precisely when taping discs.

Metering facilities become more interesting and elaborate in high-end machines, too. Aiwa's new AD-6800, for example, has recording-level meters that look quite ordinary-until you notice that they have two needles each. In normal operation, one needle on each meter reads average recording level; the other reads peak level, registering against the same scale for easy comparison. A peak-hold button causes the meter to show the highest program peak for up to 30 minutes. These meters are also used to adjust bias for the specific tape in use: a built-in oscillator feeds the tape 400- and 8,000-Hz tones, and bias is adjusted until equal readings on both meters indicate that output from the tape is the same for both frequencies. The head that reads tape out put for this test is technically a separate playback head, but it is used only for tape-calibration purposes.

Dual's C939 has another unusual metering system: no meter needles. In stead, there are arrays of seven green and five red LED's per channel. Since LED's don't have the mechanical inertia of meter needles, they can easily respond fast enough for peak-level reading; Dual also lets you use them for average-level indication at the flick of a switch.

Even the most ordinary-looking meters may contain pleasant surprises: the scales on the Akai GXC-570D, the Nakamichi 600, 700 II, and 1000 II, the Pioneer CT-F1000, and the Technics RS-9900US all read down to at least-40 dB, or 20 dB lower than the usual meter scale. (The Technics 9900's transport-on a separate chassis from its recording amplifier-has a meter that reads time remaining on the tape; one of the Aiwa AD-6550's recording-level meters can be switched to read tape time, too.) And quite .a number of machines priced from about $400 up have meters that either read peak level (as in the Optonica RT-3535 Mk II, the Sonab C5000, the Lenco C2003, the Nakamichi’s, the Teac A-303 and A-640, the two Tandbergs and the Technics RS-9900US) or can be switched to read either peak or average levels (as in the Technics RS-671US and RS-640US, the Teac Esoteric 860, the Hitachi D-800 and D-3500, the JVC CD-1970, and the Akai GXC-570D and GXC-760D).

Dolby circuits are the norm, of course, even in the least expensive cassette decks. But several of the more ex pensive models have both Dolby facilities and a second noise-reduction system. The Nakamichi 1000 II and Uher CG-362 have the DNL (Dynamic Noise Limiter) as their second system; al Dolby circuits are thee rt-Mk " norm . . . but several of he more expensive models have both Dolby facilities and a second noise-reduction system." though not as effective as the Dolby technique, it can be used to reduce noise on any tape, not just specially en coded ones. The Teac Esoteric 860 has dbx II, a compressor/expander system that can yield signal-to-noise ratios of over 80 dB. However, dbx-encoded tapes must be played back through dbx decoders; Dolby tapes, by contrast, sound reasonably good when played back undecoded.

The Teac 860's mixer is also the most elaborate found on any cassette deck: its four outputs can all be used for line or microphone inputs, with a switchable 20-dB attenuator in each mike-input circuit to prevent microphone-pre amplifier overload with high-output microphones or very loud signal levels.

The 860's mixer also has a master gain pot plus pan pots on all four of the in put channels.

All cassette decks can play for up to an hour without interruption if you use C-120 tapes. For still longer listening, Akai's GXC-730D, Dual's C939, and Uher's CG-362 will play both sides of the tape before stopping (or start over with the first side again if you prefer); the Akai and Dual will also record in both directions. If you need still more playback time, Lenco's PAC 10 not only plays both sides of the cassette but holds and plays up to ten cassettes, in sequence, by means of a system similar to that of an automatic slide projector. Additional "cassette trays" are available if you want to have the next ten or twenty hours' worth of music ready in advance. A few decks without reverse facilities (the Nakamichi 1000 II, Sansui SC-5100, and Akai GXC-570D), though they play just one side of the tape, can repeat that side indefinitely if you wish.

On the other hand, deliberate interruption is the idea behind Dual's unique "fade edit" feature. This allows you to gradually erase undesired portions of a recording for a professional-sounding fade-out. You can also fade in already recorded material. A two handed interlock ensures that you won't accidentally edit out something during play by hitting a button accidentally. You can also do a measure of such editing-out with the punch-in re cording feature on Pioneer's CT-F1000 and Tandberg's C-330. This feature, snore commonly found on professional or semiprofessional open-reel decks, lets you start recording after the tape begins to move instead of requiring that you press "play" and "record" simultaneously. Of course, this also takes an extra measure of care so that you don't accidentally record over some material that you meant to save.

----------

Time for Decision

Making the final choice is of course not easy with such riches to select from, but various pressures will help to narrow the field of choice: the state of your finances will limit it a bit, and a physical space that is suitable only for a front-loading deck-or only for a top-loading one-will cut the choice of models about in half. (Incidentally, the type of loading a machine employs has no necessary relationship to its quality.) For the rest, you'll just have to face the agony of decision, but when you do, it is-always best to be systematic about it:

1. From the models in your price range, pick the ones which have those features you cannot live without (if they also have others, fine, but don't let that affect your choice).

2. Next, test their performance at a dealer's showroom by making test recordings and comparing the deck's re corded output with your source material. Two good sources to use are fresh discs of wide-range music (discs have a wider frequency range than FM, and they can be played back for direct com parison) and the "white noise" you'll find between stations on the FM dial with the tuner's muting shut off (the latter is an extremely difficult signal for a cassette deck to record, however, and the recording should be made at a level of -10 dB or even lower).

3. If you can't tell the difference be tween the original program and the re cording of it, then the deck is good enough; if you can't afford a deck on which the difference is inaudible, pick the one whose differences are least apparent or important to you. No matter what you read on the spec sheet, it's the sound you hear that ultimately counts.

====================

Also see: Link | --Link | --Link | --Tape Talk, 1983

Jensen Sound Laboratories (1978 ad)

CLASSICAL DISCS AND TAPES (Feb 1978)

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)