THE Uptown section of New Orleans, Chicago's South Side, New York's Harlem-these were the main breeding grounds for jazz from the turn of the century, when cornetist Buddy Bolden sent stentorian blasts of raw blues through the smoke and laughter of Gravier Street honky-tonks, to the late Thirties, when Billie Holiday gave familiar lyrics new meaning and triggered romantic fantasies in the minds of silver-foxed ladies in Harlem night spots. Yes, there was jazz elsewhere. But these, few as they were, were the centers, the places where things happened-and where they happened first.

Since the Thirties, jazz has moved in virtually all directions, musically as well as geographically. Throughout the Forties, it continued to keep one foot in Harlem, but a downtown migration to West 52nd Street had begun in 1936.

There, between Fifth and Sixth Avenues, a concentration of small clubs featured, at one time or another, the greatest stars of the Swing Era. And, before 1948, when tassel-twirling strippers had taken over all but one of the block's jazz spots, "The Street," as musicians called it, had embraced bop as well. For more than a decade, 52nd Street was not just the center of jazz activity in New York: it had become a focal point to which all jazz musicians were drawn, and from which budding talent blossomed and innovations sprang.

Unlike today, when a combination of complex arrangements and unfriendly attitudes discourages musicians from "sitting in" with other groups, 52nd Street clubs were geared to impromptu jam sessions. "The feeling was so wonderful," recalled clarinetist Tony Scott. "Any time you came into a joint, they asked you to join them . . . . I used to go from one joint to another, every half-hour, like from where Ben [Webster] was playing to where Erroll [Garner] was, to where Sid Catlett had the band. I'd make the complete rounds and I'd sit in at each club." Jazz owes much of its early growth to such informal get-togethers, but they are now a thing of the past. Today's so called "jam sessions" are often contrived, routinely performed affairs that rarely provoke an original musical thought.

--------------

"The Seventies saw more and more lofts turn into musician-owned and operated clubs catering to people for whom neither rock nor electronic crossover music is the answer."

------------

THOUGH Jimmy Ryan's held out until 1962, it had already become clear, as the strippers undulated through the late Forties and into the Fifties, that The Street would never return to jazz. But, thirty years later, New York again has an area where the music flourishes: a grimy commercial district in lower Manhattan just below Greenwich Village. They call it SoHo (because it lies South of Houston Street), and it was in the Sixties that musicians, artists, and poets began occupying lofts that had once been warehouses and factories in that bleak area. Attracted by the spaciousness and the low rent (not so low any more), they originally sought these By Chris Albertson lofts as residences, and, since they were located in a nonresidential area, musicians also found them ideally suit ed for rehearsals.

At first, the rehearsals and practice sessions were more or less private affairs, but when rock came of age in the late Sixties, and New York's jazz clubs dwindled to a precious few that hired only the well-established, marketable names, loft residents began inviting appreciative audiences to informal musicales. What they offered was mostly what came to be known as the "new music," a catch-all that covers a multitude of expressions having as a foundation the works of Ornette Coleman and John Coltrane, with consider able input from Chicago's outré AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians).

Because these musical soirees quickly became popular, and because commercial outlets for this largely inaccessible music were limited, the Seven ties saw more and more lofts turn into musician-owned and-operated clubs catering-with soul food and sounds not likely to be heard on the Tonight Show-to people for whom neither rock nor electronic crossover music nor even the polished sound of a Getz or Brubeck is the answer.

SUCH major record labels as MCA, Capitol, RCA, and Columbia have so far ignored loft music, making it necessary for many musicians to record and issue their own performances. This is an arrangement that tends to yield a more artistically satisfying product, but also one that-due to lack of promotion and almost nonexistent distribution rarely brings the artist a just financial remuneration. Now Douglas has re leased a five-album series entitled "Wildflowers: The New York Loft Jazz Sessions" containing twenty-two performances recorded during seven evenings in the spring of 1976. All the recordings were made before a live audience at Studio Rivbea, a loft owned and operated since 1971 by saxophonist Sam Rivers and his wife, Bea, who also make it their home. While these recordings by no means form a complete picture of New York's slowly emerging underground jazz movement, there are enough catalytic figures involved in them to make this an important, worth while glimpse. Unfortunately, producers Alan Douglas and Michael Cuscuna have included in the set a few examples of this music at its worst. But perhaps even that is as it should be, for it is plain truth that all that shakes the rafters of the lofts is not profound.

-----------

Bassist Chris White--whose experiences in that big, commercial outside world include long stays with Dizzy Gillespie and Billy Taylor as well as stints with such veterans as Eubie Blake and Earl Hines-kicks off "Wildflowers 1" by laying down a solid foundation for the big-toned tenor of Kalaparusha (ne Maurice McIntyre; exotic names are extremely popular with the loft crowd), whose Jays shows him to be more earthbound than most of his colleagues. There is more character to Ken McIntyre's glib alto runs and figures on New Times, which has the quartet's pianist, Richard Harper, and two percussionists stomping to a smart climax. The music of Harold Arlen isn't exactly loft material, but alto ist Byard Lancaster, with Sunny Mur ray and the Untouchable Factor, gives Over the Rainbow an elasticized treatment of which even Dorothy herself might have approved. Rivbeaproprie tor Sam Rivers is a highly original and logical improviser whose artistry is well represented on several Impulse and Blue Note albums, but who is per haps at his best on two superb duet recordings with bassist Dave Holland, recently released by the Improvising Artists label ("Dave Holland Sam Rivers," IAI 373843 and "Sam Rivers Dave Holland, Vol. 2," IAI 373848). In "Wildflowers" his soprano saxophone makes a feverish, stunning statement on Rainbows, which is as far removed from the Arlen tune as Soho is from Oz. Altoist Henry Threadgill's LSO Dance gets phenomenal bass support from Fred Hopkins, ending the first al bum with shades of 1959, when Ornette Coleman (who has his own loft) shook the foundations of jazz by removing its chord structure.

"Wildflowers 2" gets off to a fine start with pianist Sonelius Smith's A Need to Smile, which Smith plays with a seven-piece group called Flight to Sanity. Regrettably, technical problems made it necessary to scrap the opening, but the salvaged eleven minutes show this to be a cohesive unit, and the solo work, by Smith and saxophonists Byard Lancaster and Art Bennett, is excellent. Equally fine is Ken McIntyre's Naomi, a tranquil, sensuous piece featuring his flute and more of Richard Harper's lyrical piano.

Reed player Anthony Braxton is currently perhaps the best-known player on the new-music scene and one of the few who is recorded with some regularity by a widely distributed label. He is capable of playing his instruments with conventional warmth and grace, but he often opts for the bizarre. The excerpt from his 73°-S Kelvin, included here, combines smooth alto runs with ear-grating squeaks, grunts, and whines that-if the applause on the record is any indication-pleased the crowd at Studio Rivbea more than it did me.

Braxton, an AACM alumnus, can be heard to far greater advantage on any of his five Arista albums.

Marion Brown's And Then They Danced takes up seven minutes of "Wildflowers 2," but the former Archie Shepp and John Coltrane side man-whose own sidemen here, bassist Jack Gregg and conga drummer Jumma Santos, barely get a note in gives us but an alto exercise in tedium.

Trumpeter Leo Smith and the New Delta Ahkri, a group that also features alto saxophone player Oliver Lake, end the second album on a more interesting note with Locomotif No. 6, a slightly disjointed piece of impressionism by pianist Anthony Davis.

Pianist Randy Weston is not someone one would identify with the new music, nor, for that matter, with the loft scene, but that is simply because of his success in the commercial world during the late Fifties and well into the Sixties (remember Little Niles?). Musically, Weston has always been advanced and eclectic. His Portrait of Frank Edward Weston, which also features his son Azzedin (the original "Little Niles") on conga, begins "Wildflowers 3" and offers striking proof that jazz does not have to for sake its roots to be au courant.

Much the same can be said of guitar ist Michael Jackson's Clarity (2) and pianist Dave Burrell's Black Robert; the former contains some particularly impressive flute work by Oliver Lake, and the latter reflects the multitude of influences Burrell is fond of citing. Trumpeter Ahmed Abdullah's Blue Phrase is a boppish, Mingusy, throbbing piece that builds magnificently and contains excellent individual performances by the leader, saxophonist Charles Bracken, and guitarist Mashujaa, the whole propelled by one of the most hotly pulsating rhythm sections (drums and two basses) I've heard in a long time.

The calculated chaos of the album's final cut, an excerpt from Short-Short, played by Andrew Cyrille and Maono, is less to my liking, but it has its points and should not really be judged out of context. Cyrille, whose diverse experience includes playing sideman to Nellie Lutcher as well as Cecil Taylor, is too often overlooked when drummers are being discussed.

Just why and by how much Short-Short was shortened by the producers is nowhere explained, but the six and a half minutes of Hamiet Bluiett's Tranquil Beauty that form the opening track of "Wildflowers 4" could have been put to better use. It's a slow, down home blues on which Bluiett's clarinet captures the reedy New Orleans tone well, but both he and trumpeter Olu Dara fumble their way so badly through this most basic of jazz expressions that it almost has to have been de liberate. A brief baritone passage at the very end saves the track from total disaster, and if this is indeed an attempt to parody the music of stumbling, resurrected Crescent City veterans, I fail to see the purpose-planned mediocrity is something I think we can do without.

------------

Pensive is an apt title for altoist Juli us Hemphill's contribution to this series, and a fine contribution it is; cellist Abdul Wadud and guitarist Bern Nix give this piece a somewhat romantic aura, but there is a sardonic touch to Hemphill's melancholic statement, and the juxtaposition works. Alto saxophon ist Jimmy Lyons (not to be confused with the West Coast jazz promoter) leads a quartet comprising bassoonist Karen Borca, bassist Hayes Burnett, and drummer Henry Maxwell Letcher.

Unfortunately, we are given only a little more than five minutes by this group, but Push Pull is five minutes well spent. Lyons is not well represent ed on records, but a fine example of his talent is to be found on a recent release of a 1969 Cecil Taylor concert, which also includes Sam Rivers and Andrew Cyrille ("The Great Concert of Cecil Taylor," Prestige P-34003, a three record set).

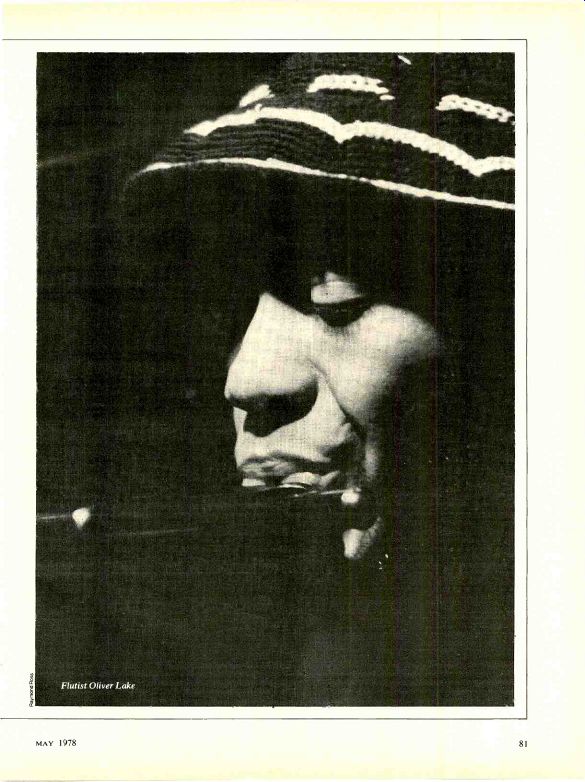

Oliver Lake reappears on "Wild flowers 4," this time as leader of a quartet that has Phillip Wilson on drums but otherwise is the same group heard on his excellent album "Holding Together" (Black Saint BSR 0009).

Lake is an articulate player who early sought inspiration in the works of Paul Desmond and Jackie McLean, but he has since headed in his own direction along the free-form route. Zaki has him playing the alto in characteristic fashion. Ending the fourth album is Shout Song by David Murray, at twenty-three a relative youngster. Murray is a tenor saxophonist of considerable promise; in the three years since he arrived in New York from California, he has established himself firmly on the loft scene. Despite his age, he cites some of the great swing tenor men as his influences, but in two and a half minutes he barely gets off the ground.

Roscoe Mitchell and Sunny Murray share the fifth, and final, Wildflowers album with one extended selection each. Murray's group, the same Un touchable Factor that does Over the Rainbow on "Wildflowers 1," shows more characteristic colors on Murray's own Something's Cookin', an emotion--charged seventeen-minute piece of intensity mounting to hysteria as seething saxophones seem to poke through bubbling rhythm. This sort of thing sound ed fresh and exciting ten or fifteen years ago, when avant-garde was still an apt description for it. But if the "new music" doesn't start to move on soon, it will eventually find itself on the same treadmill that for years has held Dixieland music captive.

One direction that seems to lead no where is that taken by saxophonist Roscoe Mitchell, whose Chant ends the Wildflowers series on an excruciatingly boring series of notes. If Mitchell has mastered the technique of his instrument, I have yet to hear proof of it; this highly overrated founding member of the Art Ensemble of Chicago seems to be emulating a stuck record as he repeats his soft squeaks and loud, un imaginative figures ad nauseam. I have heard more music in gently swaying wind chimes, found greater profundity in a Rod McKuen poem. "Wildflowers 5" is the least satisfying volume of this otherwise interesting series.

To reiterate, there is more to New York's loft jazz scene than meets the ear in this five-album series. Such places as Studio Rivbea, the Ladies Fort, and drummer Rashied Ali's very successful Ali's Alley are giving jazz a new lease on life. By encouraging experimentation, they are helping to mold the young musicians who, we all hope, will be taking the music on to its next plateau.

As the Seventies draw to a close, the outlook for jazz in New York has improved. More and more small clubs, from Greenwich Village to the Upper West Side, now have a jazz policy, and many of them are hiring musicians who until recently found themselves relegated to the loft scene. So far, the lofts, too, are flourishing, but as they become viable businesses, there is always the danger that they will either spawn too much competition or simply lose the character that has made them so valuable to the growth of jazz. Only time will tell, but let us hope that at least the strippers won't repeat their invasion of thirty years ago.

------------ NEW YORK LOFT JAZZ SESSIONS

Wildflowers 1. Jays (Kalaparusha); New Times (Ken McIntyre); Over the Rainbow (Sunny Murray and the Un touchable Factor, featuring Byard Lancaster); Rainbows (Sam Rivers); USO Dance (Air). DOUGLAS NBLP 7045 $6.98.

Wildflowers 2. The Need to Smile (Flight to Sanity); Naomi (Ken McIntyre); 73"-S Kelvin (Anthony Braxton); And Then They Danced (Marion Brown); Locomotif No. 6 (Leo Smith and the New Delta Ahkri). DOUGLAS NBLP 7046 $6.98.

Wildflowers 3. Portrait of Frank Edward Weston (Randy Weston); Clarity (2) (Michael Jackson); Black Robert (Dave Burrell); Blue Phase (Abdullah); Short-Short (Andrew Cyrille and Maono). Doluot. As NBLP 7047 $6.98.

Wildflowers 4. Tranquil Beauty (Hamlet Bluiett); Pensive (Julius Hemp hill); Push Pull (Jimmy Lyons); Zaki (Oliver Lake); Shout Song (David Murray). DOUGLAS NBLP 7048 $6.98.

Wildflowers 5. Something's Cookin' (Sunny Murray and the Untouchable Factor); Chant (Roscoe Mitchell). DOUGLAS NBLP 7049 $6.98.

----------------

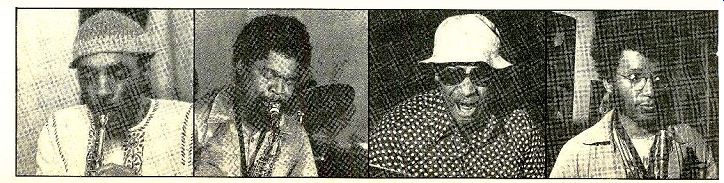

above: Some instrumentalists on the loft-jazz scene are, left to right (from facing page), Sam Rivers, Byard Lancaster, Sunny Murray, Anthony Braxton, Marion Brown, Randy Weston, and David Murray. (Photos are by Raymond Ross.)

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)