THE PASSIONATE COLLECTOR: Do people really bankrupt themselves to buy a rare disc? by PAUL KRESH

Paul Kresh explores Discomania, that little-known area of human frailty lying somewhere beyond the (comparatively) well-traveled land of Discophilia.

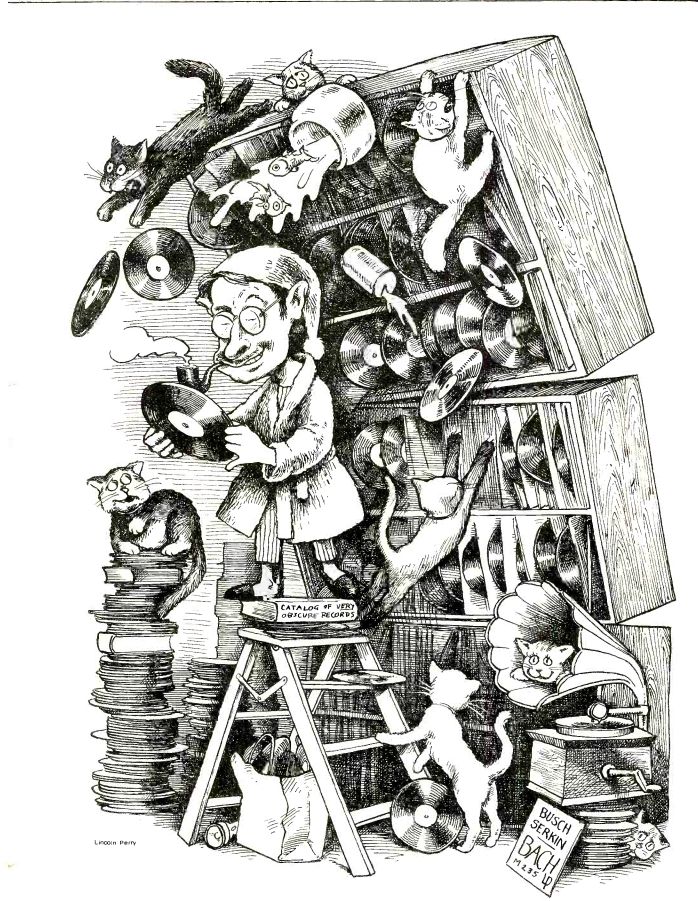

VICTOR M-235 is a 78-rpm album of J. S. Bach's Sonata No. 3, in E Major, for Violin and Keyboard that probably does not exist. That is to say, it was recorded by Adolph Busch and Rudolf Serkin and it was listed in a 1934 artists' catalog issued by Victor, but, as far as we know, no one has ever seen the records and the overwhelming probability is that the album was never released. Nevertheless, Thomas Clear is looking for it. In fact, it is number one on his wanted list. He has looked for it in Newark, New Jersey, and in Tokyo, Japan, and practically every place in between.

One day another collector, Gene Bruck, was driving through Kentucky when the highway traffic got so heavy he decided to turn off on a side road and stop at some nearby town until things eased up. Pulling into the center of a small town he had never seen or heard of before, he noticed an old Vic tor sign in the window of one of the stores. He got out of his car, went into the store, and began to poke around in some piles of old 78-rpm records. The clerk so persistently asked if he was looking for anything special that Bruck finally snapped that he was looking for Victor album M-235. "Oh," said the clerk, "You're a friend of Tom Clear's." Why do people collect "rare" recordings? What sort of people are they? What are the pitfalls that lie in wait for prospective customers? When does accumulating albums stop being a hobby and start turning into an obsession? Where do collectors go to get the stuff that crowds their shelves? And, above all, what kind of prices do they pay, what are all those rarities really worth on the collectors' market? I decided to look into the subject and soon found myself drifting through a strange twilight world and bumping into its elusive and sometimes legendary denizens. In fact, almost before I knew what I was doing, I became a collector of record collectors.

FOUND out that, just as with acquirers of stamps or butterflies or rare coins, once the appetite to build a collection grows keen it can result in personal bankruptcy, a broken marriage, or a mental breakdown. The disease takes a number of forms. There are people who specialize in classical piano discs, old 78's of certain orchestra conductors, or poetry readings in Sanskrit.

There are individuals who will assure you with a straight face (collectors, even collectors of comedy records, have some of the straightest faces in the world) that since, say, Siegmund von Hausegger died in Germany there has been nobody, but nobody, who could properly conduct a Bruckner symphony. There's a television producer in Greenwich Village (his name is Michael Levin) who owns 70,000 LP's, 5,000 cassettes, 2,000 ten-and-a-half-inch and 1,000 seven-inch reels of tape.

There's a record-company executive in Manhattan whose apartment is so crowded with records that he can't get through the room to his own record player to play one of them.

A friend of mine who deals in rare recordings and is also a recording engineer with a deep interest in the history of the industry believes that many people who collect records do so to rein force their own identity. Sometimes it is a matter of nostalgia-buying up old 45-rpm singles, for example, because that is the musical material they were imprinted with when they were growing up. But he has also run across collectors with what he calls "Collyer Brothers mentalities." One man, for example, a former Victor Record Company employee, not only held onto copies of every Victor record he could lay his hands on, but also kept obscure company publications, such as a catalog of movie music suitable for playing with silent films, company letterheads, business papers, and other artifacts, until his home became a kind of duplicate of the old Victor headquarters in Camden, New Jersey.

My own experiences in this realm had long been confined to simple at tempts to obtain certain out-of-print items I hankered after for the naive purpose of playing them once in a while. This is chicken feed, however, compared to the expensive (in time and/or money) preoccupations and quests of real collectors-or to those of tracking the collectors themselves down. My attempts to connect up with the fabled Thomas Clear, for example,

"On the rare-record market, at least, today's original-cast flop can turn into tomorrow's hit."

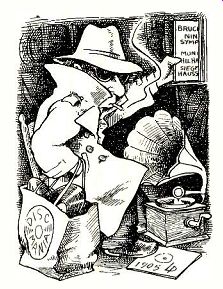

entailed such preparations as might have been worth a chapter in a book like The Spy Who Came In from the Cold. Mr. Clear was known to be a shy spirit who did not seek publicity. He had no telephone at home and was to be found, through the proper intermediary, only at a certain bar he frequented in midtown Manhattan at hours that could not be predicted with any certainty.

Finally, late one night, my messages drew a telephoned response from the gentleman in question, and one spring evening he arrived at my apartment in Greenwich Village wearing an oversize black raincoat and a somewhat battered hat and carrying a shopping bag containing, among other things, a limit ed-edition LP of the "Augmented History of the Violin on Records," Volumes Seven and Eight: the violin concertos of Wolf-Ferrari and Nussio played by Guila Bustabo. For Clear not only collects records but, in a quasi-amateur capacity, sells copies of certain items from his collection to favored purchasers. It was in his role as a collector, though, that I had been advised to see this man, who has the look of the seasoned seaman he is (he served for many years in the Navy and later the Merchant Marine). Grey haired now and in his late fifties, Clear was born in Philadelphia and says he started getting interested in records when he was about four.

"My father had a small collection of old acoustic records by Caruso, Stokowski, and so forth. He used to play them for me and read stories from the Victor Book of the Opera and it sort of caught my interest. . . ." A familiar pattern, I was to learn, in case histories of severe record-collection addiction. Clear was all right, though, until World War Two came along and he was serving as an officer on an aircraft carrier in the Pacific.

During the invasion of Okinawa in 1945 he was hit in his right knee with a piece of shrapnel, which relegated him to the sick list for more than a month. And then it happened: "The ship's warden had a library of records which some body had given them in San Francisco.

One of the items in the library was Bruckner's Ninth with the Munich Philharmonic under Siegmund von Hausegger. The work had such a spiritual effect on me that I actually think it helped my recovery." Clear has traveled all over the world searching for additions to his library. In Tokyo he used to confer with the late Fukio Fujita, head of the Japanese Gramophone Society and one of the foremost collectors in Japan. (Clear and other collectors complain that with the yen worth so much these days the Japanese are cornering the entire rare-record market.) When he left the Navy as a regular line officer he joined the Merchant Marine. He would work in the engine room, patiently waiting for a port where he could forage in record stores for rarities.

Like many other collectors, Clear is a man of strong and unshakeable opinions. He despises most contemporary music and thinks stereophonic sound was a setback in the progress of musical reproduction. The word quadraphonic can send him reaching for his hat and his shopping bag. He thinks orchestra conductors have grown progressively worse, recorded performances sloppier through the years. He plays his own records on a time-honored turntable through a mono amplifier and one big speaker. He likes best to play his old 78's.

"When I have to get up every four minutes to change the side, then I feel I am participating. With an LP I can't concentrate on it as much. I begin to dream of other things and my mind wanders, and soon I'm doing other things-like writing letters. But I never read when I play records. It's either one or the other." Teri Towe, a thirty-year-old collector who returned my next call, invited me to see his collection, admire the sturdy metal shelves he keeps it on (there must be more than 10,000 discs), and talk about the subject. The son of Kenneth C. Towe, president of American Cyanamid, Towe grew up in Greenwich, Connecticut, studied art history at Princeton, where he won the Frederick Barnard White prize for the best thesis on the history of architecture, and is today a partner in the law firm of Barkhorn, Ganz, and Towe, where he deals in trusts and estates as well as in cases involving the entertainment industry. He also writes-liner notes for RCA and the Musical Heritage Society-and ghost-writes articles, including a recent one for a "girlie" magazine.

'WE started with children's records, but by the age of five he was already into the classics. He likes Baroque mu sic best. "

I've always had a passion for Bach, if you'll pardon the pun." The subject became something of an obsession in the days when he was going to prep school in Deerfield, Massachusetts. "The world is divided," Towe says he learned, "between those who collect and those who don't. I know a woman who collects friends. I collect music."

Towe, like Tom Clear, has never paid more than $100 for a record. He doesn't see spend $75 for an original Caruso when I can get the complete Caruso on the Murray Hill reprint label for $29.95." Towe is quick-as are most collectors-to dispel the popular myth about the alleged value of those old Caruso records in your grandmother's attic.

The more copies of a record pressed, the less valuable it is likely to be; Caru so records particularly were turned out like pancakes.

From Mozart's Jupiter Symphony (Victor M30, with Albert Coates con ducting) Towe's collection grew over the years to include Bach fugues, Scarlatti sonatas, organ recitals, violin recitals by Albert Spalding (he considers the violinist much underrated) and Yehudi Menuhin, and piano records by Alfred Cortot. Later he added records of music by Stravinsky, Roger Sessions, Ned Rorem-even Milton Babbitt. His opinions are strong: "I do not like Tchaikovsky, I think his music is ghastly . . . Toscanini was a great conductor. I just don't particularly care for the way he did things . . . the mu sic does not breathe . . . ." One of the rarest items in Towe's collection is a private recording of the Schubert C Major String Quintet per formed by Pablo Casals and the Buda pest String Quartet. He saw it at David Rockefeller's one evening in 1960 when he was at a party there and managed to acquire it. Cost: $100.

So who is paying all the alleged high prices for rare recordings? A company in Lacey, Wales, called Ticket to Ryde, Ltd., which specializes in Beatles records (they stock 1,700 Beatles records from thirty countries), recently sold an extremely rare item for $1,500, but the company has never gotten more on any individual sale. Some dealers, of course, operate on the whatever-the-traffic-will-bear principle, but it is only once in a long while that any record actually goes for over three figures.

What makes a record valuable? Rarity is a factor, of course, but rarity by itself isn't enough. There are certain records whose prices go up because at some point the bidding for them be comes strongly competitive. The price of one old 45-rpm single soared to $3,800 when two rivals tried to outbid one another for it. Morbid curiosity makes certain issues "desirable" and expensive, as was the case with a vocal release featuring the voice of murderer Charles Manson. Original format counts: an early Victor show album with a green label will fetch more than a later release with a black label. The original RCA pressings of Two's Company was bringing in about $75 up to the time it was reissued in Australia, but even after that the American original was still worth more than $50 (the price went down again last year when RCA reissued the album here). But supply and demand is the main operating principle. A recording put on the market in small quantities in the first place will soar in price when and if it becomes an item sought out by collectors. On the rare-record market, at least, today's original-cast flop can turn into tomorrow's hit.

SAM HOLMAN is an accountant who collects show albums and spends as much of his time trying to keep his collection down to size as adding to it. He has about 1,200 records but no room in his apartment for more. He has eliminated all the bulky 78's from his shelves. He too doesn't believe in spending "huge sums" on his hobby.

The most he ever paid was an average of $25 each for three original-cast recordings-Arms and the Girl, This Is the Army, and Texas L'il Darlin'. And he is more interested in the contents of a record than in how it sounds. At the moment, he is trying to get hold of sever al old British show albums, including one called Chrysanthemums. His wife has no interest in his hobby, prefers the radio to records, and keeps pretty much out of this side of his life. Recently, when she was out of town, he played through his entire collection of Ray Noble records of Thirties dance music.

Tom Morgan, who lives in a spacious townhouse on New York's Upper East Side, specializes in collecting the vocal classics. He is a stout, comfortable man and looks happy in his big living room surrounded by ceiling-high shelves containing his acquisitions.

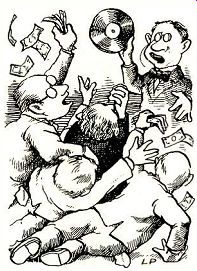

"Collectors," says Morgan, "are a rather nutty lot who just have a fanatical desire to get things that are hard to get." He admires those who go after what they enjoy hearing rather than after rarities. "So many of them squabble among themselves about the price of this or that and bargain-you give me two records for this and I'll give you three records for that." He suggested that if I wanted to find out more about how collectors bid for auctioned material I ought to go to one of the monthly meetings of the Vocal Record Collector's Society.

The following Friday I turned up at the next meeting of the society (" America's oldest and largest vocal classical record society," it says on their stationery) at Freedom House on West 40th Street in New York City. In a spacious, brightly lighted, air-conditioned room that July evening, members were gathering for the program: an auction of items from the rare records accumulated by dealer/collector William Violi, followed by a concert of vintage vocal recordings he had brought.

The meeting was called to order by a man named Joe Pearce. Then Violi, grey-haired and pink-cheeked, started the auction going: "A very nice copy of the Victor catalog for 1929 . . . any bid for this 1929 Victor catalog, practically mint condition? One dollar . . .

two dollars . . . two dollars once

... twice ... " It was Teri Towe who walked off the with catalog for two dollars.

"Now we get to this ten-inch record.

A 78. Dino Borgioli and Gino Vanelli . . . a pre-war English Colum bia. . . One dollar . . . two dollars ... three dollars ... once, twice, thrice ... A. Vesselowsky, tenor ... beautiful Fonotipia Series repressing

...excellent surfaces...Seventy eight rendition of the Night in Carnegie Hall movie with Pinza, Stevens

... any interest in this particular set? One dollar for three records? Two dollars? Three dollars? Ah! Thank you, Miss Green." LEFT the meeting with a list of hun dreds of items available for auction to the members. Later I received a letter from Mr. Pearce stating that the real ized bids on these records had brought in over $1,000. "There's no end," he wrote, "to what a collector will pay to insure lifelong poverty." During that meeting, Teri Towe had introduced me to his friend Donald Hodgeman who was in from California and whom Towe characterized as "the greatest collector in the world," but Hodgeman didn't want to talk to anybody.

Such reticence is especially characteristic of collectors who work within the record industry. I spoke to several record-company executives, however, who did agree to talk about collecting if I would withhold their names. One of them told me he still has the first record he ever bought-a version of The Blue Danube with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra on Decca. He got that in 1949.

Then his mother took him to a concert of the Philadelphia Orchestra with Stokowski. They played the prelude to the third act of Lohengrin and he thought it was so great he went out and bought that the next day. Today he owns some 20,000 records and nearly a thousand tapes.

He specializes in early orchestral material, but he goes after vocal records too when the singer is of particular interest to him. This collector has first rate equipment and when he can, especially during vacations, will listen to records from morning to night. His fondest wish is to have "a complete run of all the Beecham records," but he has despaired of getting certain of the acoustic ones from the years 1911 to 1917. This fifty-one-year-old executive thinks most collectors are too quick to dismiss the technical advances of recent years. He prefers a good performance to a good recording in sonic terms, but "I certainly wish Caruso had recorded in quad." The most he ever paid for an item was $750 for three &elector...". . .one man wanted a recording of an opera he called 'Mr. Rosen and the Cavalier.' " unissued Maggie Teyte recordings. The least was fifty cents for seven Beecham acoustic recordings. He got those at a tag sale near Pound Ridge, New York, which he had gone to, reluctantly, with his wife. On tapes he has never spent anything-just takes the stuff off the air.

One record-company executive who specializes in vintage jazz has six phonographs in his Long Island home and can never remember which ones he turned off before he went to bed. "I have a 78 room and an LP room. Last night I was listening to 78's in one room and then I turned the machine off and went to the living room and listened to some LP's there, and turned off half the machine. Then I had to go back to the 78's and turned the machine on, then turned off only half of that one.

When I was upstairs and about to fall asleep I said to myself, 'I didn't turn the machine off,' and I was too tired to go back down, and so this morning the machine was still on. . . ." This fellow does a lot of traveling.

One time he bought a huge collection of jazz and blues 78's in London. His son, who is twenty, was with him, and together they tried to lug six boxes containing six hundred 78's past the airport gate to the plane. An airport worker stopped them: "You're not allowed to have more than one handbag per person, and it must be a certain size to fit under the seat. All these exceed the dimensions." The records would still be in London except that an airport super visor intervened at that point and allowed father and son to board the craft with their boxes. There would have been trouble on the plane too, but the purser on the flight turned out to be a knowledgeable record collector him self and saw to it that everything was stowed safely. "He's probably the only purser flying on an international airline who collects 78's, and I had the luck to meet him on my flight." Music Masters is a store where collectors can go not only to obtain unusual and rare recordings but to relax in a living-room atmosphere. On some mornings they even serve coffee to shoppers. The shop, in the West For ties in Manhattan, is presided over by Will Lerner, the owner, assisted by manager Steve Hockstein and two other employees. Lerner says he will get for a customer "anything that was on 78's or on LP" and put it on a cassette.

He tells tales of collectors so furtive and afraid of wifely criticism that, years ago, in the days of 78's, "there was one guy who used to have us deliver stuff to him on his roof. He would wait for his wife to go out shopping and then bring the records down. It seemed to the wife that their shelves were bulging more all the time, but she never did see her husband walking into the place with an album." ONE of Lerner's customers was nicknamed "What's New" because he'd always be poking his head in the door to ask what had turned up since his last visit. "Now he's moved to California, but he calls me and asks me over long distance, 'What's new?' " Customers at Music Masters include such celebrities as Peter Ustinov, Lee Strasberg, and Joanne Woodward. The store will go to considerable lengths to keep the good will of its regular patrons. One of them was looking for "rehearsal recordings" with Toscanini.

Lerner simply picked up the phone and called Munich to locate some for him.

"I love some of the people who come in here," Lerner says, "a lot of them progeny of that lady in The School for Scandal. Recently one man wanted a recording of an opera he called 'Mr. Rosen and the Cavalier.' Couldn't find it anywhere! Another wanted to get hold of the 'Symphony on a French Mountain Horn.' He's probably still trying."

--------------------

ADVICE FOR PROSPECTIVE COLLECTORS

Don't let collecting records be come addictive, or a substitute for all other interests. Don't let the fever to fill up your shelves spoil your marriage, alienate your friends, or make you reluctant to part with money that should be spent on other things.

Don't allow your job to become merely a means to fuel your collecting habit. Don't let your collection become a mere shrine, a stack of shellac and vinyl objects to be count ed, catalogued, and admired but never enjoyed as music. Don't, in short, let collecting recordings be come the only reason for your existence. Let it enrich your life, not run it. Don't spend beyond your means.

Do build a "skeletal" foundation for your collection first, centering around some area of particular interest to you. Do learn as much as you can about what is available. Do go to dealers rather than waste time at secondhand stores. Do examine each item of merchandise carefully.

Do talk to other collectors whenever you can; get to know them by joining the various societies to which they belong. And never try to collect absolutely everything, even in your chosen category; you never will. Do know what your financial limitations are.

WHO gets taken, and who does the taking, if any, in all this? As in any other field, it's a matter of caveat emptor. New collectors are advised first to get hold of The Record Collectors Price Guide ($7.95; 2218 E. Magnolia, Phoenix, Ariz. 85034). It's regarded as the Authorized Bible of record prices, the latest edition listing more than 28,000 titles. And STEREO REVIEW is making available a list of publications, clubs, and record dealers both for those interested in launching themselves as collectors and for those who merely think they have found a treasure in the attic.

Simply write for Collector's Guide, STEREO REVIEW, 1 Park Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10016, enclosing a stamped, self-addressed envelope.

--------------------Also see:

AUDIO BASICS: From Infrasonic to Ultrasonic.

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)