by RALPH HODGES

FROM INFRASONIC TO ULTRASONIC

WE'VE all heard of infrared and ultraviolet light. The terms refer to the vast number of light waves that lie below the ruby red and above the subdued violet that mark the frequency limits of the light spectrum visible to the human eye. But invisibility does not automatically mean imperceptibility: as visitors to high mountaintops soon learn, ultraviolet light can produce a quick and ferocious sun burn (at low altitudes most of it is blocked by the earth's atmosphere), and we can readily enough detect the heat from the infrared electric lamps that keep fast-food hamburgers warm for hours. These physiological reactions are about the only means our unaided senses have of discovering that such light frequencies are present. Don't be fooled by the visible red of the infrared lamps and the purple of the "black-light" ultraviolet lamps in discos. True, you do see light coming from these devices, but that's merely an extra that lets us know they are in operation.

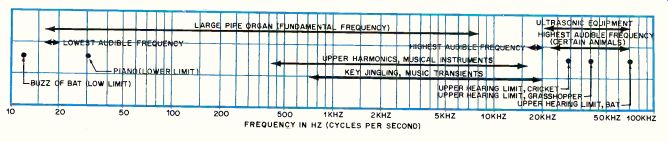

And so it is with infrasonic and ultrasonic sound frequencies. Certain physiological clues may tell you they are present: powerful infrasonic sounds will shake the floor, the dishware, and your gut; intense ultrasonic sounds have been proposed as a weapon of war because they are capable of creating great pain and a rapid breakdown of body-cell structure (fortunately, suitable sonic projectors would be cumbersome and not very efficient, so it seems likely that tomorrow's weaponry will get you in some other way).

But although our eardrums are definitely agitated by these sounds, there are no receptors to convey the message to the brain. We may perceive them in one way or another, but we do not really "hear" them. The size of the inner ear seems to have something to do with this. An adult male whose ears are in good condition may "hear" sounds from 16 to about 15,000 Hz. An adult female, typically being somewhat smaller, will not "hear" low frequencies as well but will usually detect significantly higher frequencies. Children, smaller still, may pick up sounds well above 20,000 Hz, though they have yet to report hearing anything of great interest up there.

As almost any specification sheet will tell you, high-fidelity systems strive to do a creditable job of sound reproduction over the frequency range of at least 20 to 20,000 Hz. This seems a reasonable compromise considering the probable hearing acuities of all members of the family, and it is practically no compromise at all when we look at the frequency range of musical sounds. In terms of hertz, string basses reach down into the low 40's and big bass drums may sound a fundamental pitch somewhere in the low 30's. At the higher end of the spectrum, the fundamental pitches of all musical instruments are encompassed by a 20,000-Hz upper limit with more than an octave to spare, though the overtones of some instruments have been measured as extending much higher. All this is academic, however. The atmosphere absorbs ultrasonic sound frequencies just as it absorbs--or scatters--ultraviolet light frequencies. At any reasonable distance from a musical instrument, even the keenest ear will hear nothing of significance above about 16,000 Hz, and no musical instruments are designed to put out much energy beyond that.

But what about a large pipe organ, which may have a rank of 32-foot open pipes capable of emitting a low C at about 16 Hz? Well, this is in part intended as drama, as even a few motion pictures have acknowledged with their sonic simulations of earthquakes and exploding bombs. A powerful organ can make the air around you shudder with a virtually inaudible but definitely palpable low note. If that's the experience you want in your listening room, well and good, but you'll pay for it in the coin of giant woofers and truly mighty amplifiers, only to discover that precious few recordings even attempt to capture this sort of signal. And do not be fooled by overenthusiastic claims; electric basses, kick drums, and the rest are all 40 Hz and above in frequency. Nothing else even approaches the depths plumbed by the big organ, although there are plenty of instruments that can make you feel an impact in the pit of your stomach, largely because of the amount of energy they put out at moderately low frequencies. If your (audio) system can cope with these, it will give a good account of the big organ pipe as well, in the form of its dense and powerful overtones at 32, 48, 64 Hz, etc.

As we become more sophisticated in the re production of sound, we are beginning to realize that infrasonic and ultrasonic capabilities in an audio system are not only somewhat irrelevant but also frequently undesirable. A close reading of Gary Stock's article on record players this month will reveal some of the difficulties a sound system can get into when it responds to infrasonics. None of these effects do the ear any particular good, and it's unfortunate that very few people realize the havoc they can raise with the reproduction of sounds we really can hear.

------- FREQUENCY IN HZ (CYCLES PER SECOND)

AT extremely high frequencies there are other problems to consider. There is some upper frequency limit beyond which no audio device can go without some form of distortion taking place. With modern amplifiers the limit might be 200,000 Hz or even considerably higher, but it is there nevertheless. Subject an amplifier to signals of significant strength at these frequencies and you provoke a condition of nonlinearity that can create difference tone distortions and other phenomena that can crop up at frequencies within the range of hearing. Where might such ultrasonics come from? Probably not directly from any recording you're likely to buy, nor from any phono cartridge or tape deck you're likely to use (although there is some debate about this). But they can certainly come from radio-frequency interference, oscillations and other instabilities within the amplification chain, peculiar interactions between components and their connecting cables-quite a lot of places, in fact.

We don't know a great deal about these effects, and every sound system is bound to be a little different in the way it experiences them, but from what we do know, it seems that infrasonics and ultrasonics are not very important to the reproduction and enjoyment of recorded music. Keeping them out of the reproduction process, however, may be.

AUDIO BASICS: From Infrasonic to Ultrasonic, RALPH HODGES

AUDIO QUESTIONS and ANSWERS: Power vs. Volume, Carbon-fiber Components, Line Inputs, by LARRY KLEIN

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)