You can evaluate a pressing visually once you know what to look for and how it is likely to affect the sound

By David Ranada

EVERY serious record buyer should be able to tell something about the pressing quality of an analog disc from a visual inspection. Not only is such skill valuable when you're considering the purchase of used records, but some of the techniques can be applied when you're buying new discs. Of course, most new records are securely wrapped "for your protection," but records purchased by your friends are not, and a quick glance at a friend's copy will give a good indication of the types of faults you may find if you purchase the same album.

With the help of James Shelton, president of Europadisk (one of America's top disc-manufacturing operations), I've assembled a rogues' gallery of common visible disc defects, any of which would cause a pressing to be rejected at Europadisk. Almost all these defects indicate sloppiness in the pressing or disc-mastering processes. Many of the faults are difficult to see with the naked eye, and even harder to photograph, so I've provided some verbal and sonic descriptions too. When listening for the effects of the various faults, remember that their audibility varies tremendously with the type of music being played. I've heard some extensively scratched rock and disco pressings that sounded just fine because the low-level ticks produced by the scratches were masked by the music.

Shrink wrap. Know your shrink wrap. Low-cost shrink-wrapping machines are used by many record dealers to reseal used and/or possibly defective pressings. The type of plastic used in these machines differs in texture and thickness from most shrink wrap used by major disc manufacturers. Familiarity with "authentic" shrink wrap will help you detect resealed discs. Also be suspicious of shrink wrap applied over notches or holes cut in an album jack et. Such holes merely indicate that a disc is a cutout or overstock, not that it is defective. They are cut after the authentic plastic wrapping is applied, so there should be holes in the wrapping too.

Cleanliness. Cleanliness is next to godliness when it comes to disc care and noise levels. When you take a record out of its inner sleeve for the first time, check whether it brings along its own supply of dust and debris (it shouldn't) from the inner sleeve, the pressing and packaging environment, or previous handling. The machines that trim off excess vinyl after the pressing cycle may leave slivers of vinyl attached to the edge of a disc; such slivers can become detached only to be caught in the inner sleeve or on the disc surface. Remove these slivers promptly, for if they are caught between the sleeve and the disc when the disc is replaced in the inner sleeve, they may abrade the disc surface. (This is why Europadisk's James Shelton prefers tight shrink wrap for pack aging new discs. The loose wrappers used for many audiophile releases encourage the jacket, inner sleeve, and disc to slip and slide against each other during handling, in creasing the chance of damage from gritty debris.)

Scratches. It's obvious that a brand-new pressing should not show any scratches. But not all visible scratches (on a used disc, say) will be audible. The audibility of a scratch depends on its severity (depth), on exactly where the stylus traces the groove, and on how loud the music is when the scratch passes. Don't think that every tick and pop you hear is caused by a scratch. Scratches are responsible for ticks and pops that re peat with every revolution of the disc.

Molded-in defects (such as dimples and blisters) produce less high-frequency noise and are heard more as thumps. Random ticks and pops stem from poor-quality vinyl or from dust and debris.

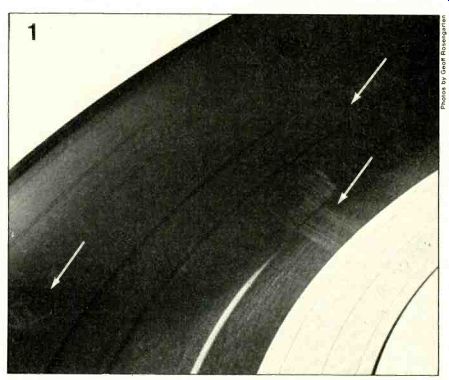

Fingerprints and scuffing. Grimy and greasy fingerprints collect dust. Naturally, they should not be present on a new pressing (or a used one either if it has been properly handled). Sometimes what look like fingerprints are not actually made by un sheathed fingers but by gloved hands handling a disc made from master discs that have not been "dehorned." The master-disc cutting process throws up little ridges, called "horns," beside the newly cut groove.

Because these are outside the groove, they shouldn't have any audible effect on the music. If they are not removed early in the mastering process, however, they can create problems in making a low-noise disc stamper. Horns molded in vinyl are easily abraded (by a gloved finger, for instance), leaving scuff marks on the disc surface (Photo 1). The disc may become noisier in these spots. You can tell whether your disc's masters were dehorned by rubbing your fingertip (shielded by a soft cloth glove or piece of paper) across the surface of the disc. A dehorned disc will not scuff.

The label. See if the correct label is on each side of the disc. You'd be surprised how often it isn't. Playing the disc is not necessary to check this out; just see if the matrix number scratched or engraved in the disc's lead-out (spin-out) area matches the number on the label.

The condition of the disc label can also indicate the quality of the pressing. It's surprisingly easy for pressing machines to slip out of alignment, the audible result of which is an off-center disc with a once-per-revolution wow. Among the necessary alignments are those that center the label; thus, an off-center label may indicate a mis aligned press and an off-center pressing. A very off-center label might even extend over the locked groove at the end of a side.

Besides being centered, a label should be flat. Sometimes moisture in the label paper is not fully removed when the label is applied, leading to a bubbly label when the disc is pressed. The vapor released by the hot pressing process has to go somewhere, and it can easily end up between the stamper and the vinyl-voila, more noise.

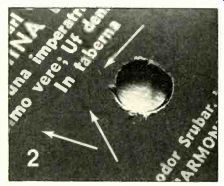

Center hole. Beware of center holes that aren't perfect circles. An elongated center hole indicates an eccentric disc and points to a too-short cooling period in the pressing cycle or sloppy alignment of the pressing machine. Debris around the center hole (from the vinyl or the label) can interfere with changer operation and with disc placement on a manual turntable. On used records, tracks around the center hole-made by a turntable spindle as the disc's previous owner(s) searched for the hole by feel-can give some indication as to how often the disc has been played (Photo 2). A used disc with an extensive trail network around its hole has probably been played too often to risk purchase.

Orange peel. The lead-out or spin-out area on a disc (the surface between the last modulated groove and the locked groove at the inside of a disc) can be used as a sensitive indicator of pressing quality. Ideally, this area looks absolutely flat and mirror-smooth. The most common and easily found fault is descriptively named "orange peel." It appears as an orange-peel-like texture of the spin-out area and is heard as noise in the low to midrange frequencies (Photo 3). The orange-peel effect comes from insufficient polishing of the back of the thin metal disc stampers. The somewhat rough surface of the back of the stamper is transferred-by the pressure of the disc-making process-to the front of the stamper and thereby to the surface of the pressing. Circular texturing in the spin-out area concentric with the disc center occurs when the finish of the mold faces (to which the stampers are cemented) is transferred to the disc.

--------

Sleeve and disc-cleaner damage. Also examine the lead-out area for traces left by the inner sleeve or by a liquid record cleaner. These look like water spots on the disc surface (Photo 4). Those caused by plastic inner sleeves stem from chemical reactions between the vinyl compound and the plastic of the sleeve. Water marks left by a record cleaner indicate that not all of the fluid was removed during cleaning, leaving it to dry in place. Regardless of origin, pressings with any such marks should be avoided since they are apt to be noisy.

Damaged stampers. Thin disc stampers are very fragile. Any damage they suffer will be transferred with high fidelity to the disc surface, where it can usually be heard as a low-frequency noise. Look for anything on the disc surface that makes it appear dented or folded (Photo 5).

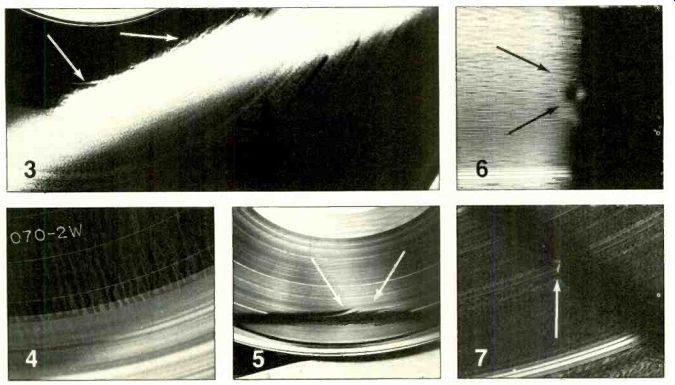

Dimples. Small indentations in the record surface are usually caused by foreign matter caught between the mold faces and the rear of the stampers. The trapped material causes the stamper to bulge out slightly, thus creating a corresponding small pit on the disc surface (Photo 6). Dimples are heard as repetitive low-frequency thumps and are quite common.

Blisters. The topological inverse of dimples, blisters (or "bubbles") are usually the result of foreign matter caught in the vinyl.

They indicate a pressing that may be noisy throughout, not just when the blister passes (Photo 7). The particles can come from bits surplus pressings is used) or insufficiently mixed and melted pieces of reused vinyl.

Blisters usually sound like dimples but can contain greater high-frequency energy and may sometimes sound more like ticks than thumps.

Non-fill or un-fill. Non-fill, as its name implies, results from insufficient filling of the stamper by the vinyl during the pressing operation, leaving an area of the finished pressing where the grooves are not completely formed. The effect sounds like a once-per-revolution series of closely spaced ticks, predominantly on the right channel for the first few minutes of the disc. It looks like a mottled greyish discoloration of the disc surface, usually within half an inch of the outer edge (Photo 8). Europadisk's Shelton says that non-fill is common on disco records, but the high overall modulation levels usually mask the added noise.

Stitching. Also called "release scuffing," stitching is heard as a ripping sound in the left channel one or two revolutions before a loud passage. It looks like a series of reflective stitches sewn along the groove path (Photo 9). Stitching can appear anywhere on the disc and can cover a wide area. It is caused by the hot, still-plastic, freshly pressed disc coming into contact again with the just-separated stamper. The louder portions of the music appear on the stamper as higher and wider ridges (on the disc as wider and deeper grooves), and if these ridges come into contact with a just-molded disc, they can deform the groove. Stitching occurs because of misaligned machinery and/or overly short pressing cycles.

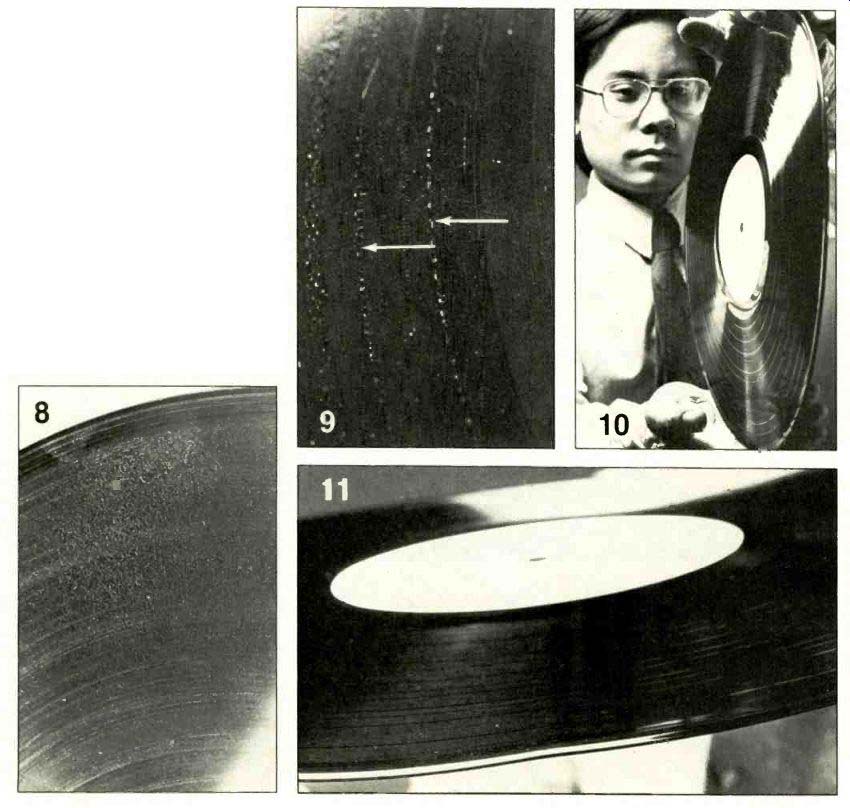

Warpage. A very common problem, warpage comes in three varieties. Dish warping, in which the disc assumes a dish or mound-like appearance (depending on which side is up), is caused by improper cooling of the disc during the pressing process. A little dishing is not objectionable, though turntable mats vary in their degrees of tolerance for dished discs because of differences in mat cross-sections.

Saddle warping (Photo 10) is also a pressing-plant defect. It can be caused by insertion of the pressing in its jacket before it is cool enough. A saddle warp is much more difficult for a cartridge to track than a dish warp.

Perhaps the most difficult warps to track are edge-pinch warps (Photo II), which are rapid and violent undulations of the outside edge of the disc. They used to be caused by pressing-machine operators who handled the discs before they had sufficiently cooled. Modern automated presses can cause pinch warps during disc trimming.

Check for all types of warps by holding the disc on edge to eliminate the disc-distorting effects of gravity.

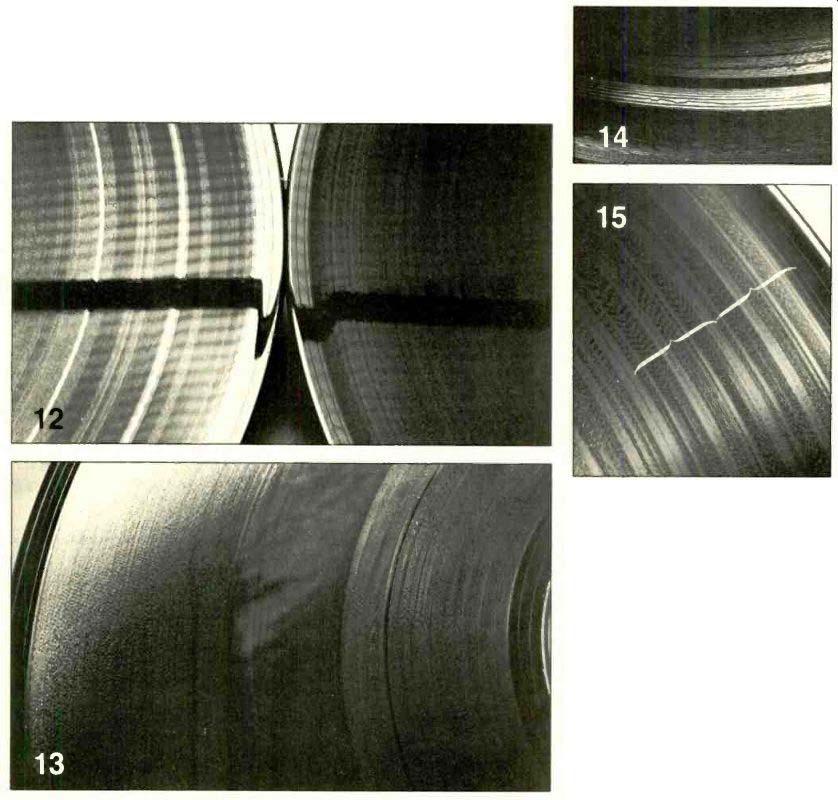

Groove guard. The raised rim of a disc is called the groove guard. Together with the raised label portion, it is meant to keep disc surfaces from rubbing together when they are stacked (as in a record changer). The groove guard is also a good source of low-frequency noise, since the stamper for the disc actually has to be deformed to make this ridge. The profile of a groove guard should not extend into the recording area (righthand disc in Photo 12), and the profile should not be very steep if the opening roar of the disc is to be minimized.

Stains. Discolorations of the disc surface can derive not only from badly mixed re ground vinyl (always an indication of higher noise levels) but also from a reaction of the chemically active nickel stampers with compounds in the vinyl. The reaction products can build up on the stamper and produce a once-per-revolution "swish" sound.

Audio quality. The disc-surface defects discussed above relate to pressing quality.

Although pressing quality affects the ultimate sound quality through its influence on background noise, the most significant factors in a disc's sound quality are the master tape and the way it has been transferred (or cut) onto the master lacquer disc. Because the cutting engineer greatly influences the appearance of the grooves on a disc, conclusions drawn from a visual examination are not as clear cut when it comes to audio quality. All the buyer can look at is the width and spacing of the grooves. But these can reveal much.

The record's dynamic range can be gauged by the variation in the reflectivity of the disc surface. Low-level passages result in closely spaced, narrow grooves that appear darker. High-level passages produce more widely spaced and wider grooves, and the disc will look lighter in loud passages. A disc with a wide dynamic range will show a considerable difference between the darkest and lightest portions of its surface. Of course, this also depends on the dynamic range of the music itself. Classical music tends to have the greatest dynamic variations and popular dance music such as disco the least.

A record's degree of stereo separation can sometimes be gauged by the variations in width of the grooves. Stereo sound is en coded as vertical modulation of the groove, and as the groove becomes more or less deep its width also changes. A mono record looks quite different from a stereo disc because the groove width is constant.

Inner-groove distortion can be estimated by seeing how close the groove is cut to the label. The closer it is cut, the more distortion there is likely to be, especially if the music is loud near the end of the side. If the same piece of music is cut at the same level on two different discs but one disc's groove approaches within half an inch of the label and the other's ends about an inch away, the latter disc (the one that doesn't look filled up) will be easier to track and have less distortion.

As a test of these principles, take a look at two very different disc surfaces (Photos 13 and 14). One disc is of high-level rock mu sic; the other is Telarc's digital recording of the 1812 Overture (complete with cannon shot). Which is which should be obvious.

Musical performance. With classical recordings you can get a general idea of the tempo taken for a piece by comparing timings for various performances of the same work. The disc surface can also reveal a few musical details. For instance, the repetition of the pattern of light and dark bands in Sir Georg Solti's recording of Beethoven's Eroica Symphony (London CS 7049, Photo 15) shows that the rarely heard first-movement exposition repeat is taken.

----------------

Also see:

Turntables: How to Evaluate the Specs

Bang & Olufsen MMC 2 Phono Cartridge