By Julian D. Hirsch

CHOOSING any hi-fi component solely from its performance specifications is always risky, but a turntable is surely one of the most difficult to assess from a mere listing of technical terms and numbers. There are few meaningful and universally accepted measurement standards for turntables, and one reason for this is the difficulty of correlating numerical turntable ratings with subjective effects on the listener.

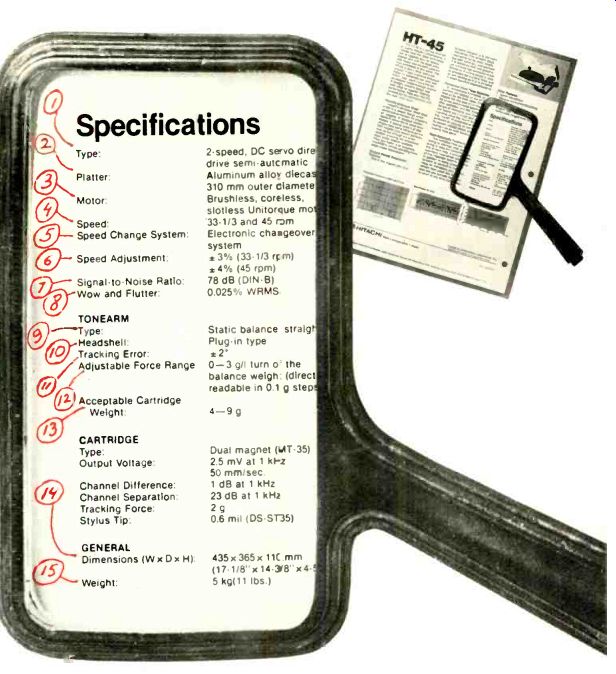

The specifications for a typical record player can usually be divided into those dealing with the turntable and its drive mo tor, those dealing with the tone arm (if one is included), and such general specifications as dimensions, weight, and power requirements. To illustrate how to evaluate turntable specs, we will examine in detail the manufacturer's spec sheet for an actual turntable, the Hitachi HT-45. This spec sheet was chosen from a pile of brochures picked up at a local hi-fi dealer because it seemed the most "typical."

1.

The type of drive system used to turn a record is often described with more specifications than most people either re quire or can understand. Sometimes the technical description is brief and even understandable by the lay user; Hitachi's simple statement that the turntable uses a two-speed d.c. servo-controlled direct-drive mo tor should suffice for even the most concerned audiophile. The precision with which a turntable is manufactured is more important than its specific drive method.

2.

The platter construction is less significant today than in previous years.

When steel platters were used in some turn tables, there was always a possibility of magnetic attraction to certain cartridges having a strong external magnetic field, thus increasing the vertical tracking force.

The universal use today of nonmagnetic platter materials makes this a moot point.

3.

Information about motor type is partly V redundant with the specification of the drive type and, in any case, means little to the lay user.

4.

The operating speed(s) is of obvious concern to any buyer whose record collection includes 45- or 78-rpm discs. Although 33 1/3 rpm is universal and 45 rpm nearly so, few new turntables today can play 78's.

5.

The speed-change system specification is essentially redundant for direct-drive turntables, all of which use electronic control circuits to establish and maintain motor speed. The speed of a belt-driven turntable, however, can be changed either electronically or by mechanically shifting the belt to a different-diameter pulley.

There are no particular performance differences between the two methods. The maximum deviation in operation from the nominal speed values is often included in turntable specifications, though not in the case of the Hitachi unit. Speed-deviation values around 0.002 percent are typical of quartz-crystal-controlled turntables, but for home use even 1 percent is usually inaudible (this is a typical speed-error specification for a cassette deck, by the way). Considering that a speed error of 0.002 percent would affect the playing time of a 1-hour program by less than 0.1 second, its importance to the home user is obviously slight.

6.

A vernier speed adjustment may be desirable for users who require precise pitch control. When most turntables were driven by induction motors, the effect of line voltage on motor speed was a meaningful specification. Today's synchronous or servo-controlled motors are essentially un affected by even the largest line-voltage shifts tolerated by the U.S. national power grid. For turntables having fixed speeds, the speed accuracy is sometimes given (it is usually far better than anyone will ever require in a home system).

7.

The signal-to-noise ratio of a turntable g is what we usually refer to as its "rumble." Rumble is the audible result of mechanical vibration from the motor or any other rotating part that causes a movement of the record relative to the cartridge stylus (or vice versa). That vibration usually occurs at low bass frequencies and produces an output signal from the cartridge whose sound suggests a low-pitched rumble or sometimes a hum.

A direct-drive motor operating at 33 1/3 rpm has a basic rumble frequency around 0.5 Hz, far below audibility or the ability of any speaker to reproduce. In most cases, however, the rumble covers a broad band of frequencies extending from the infrasonic range well into the mid-bass. Depending on its frequency distribution, it is possible for a given amount of rumble from a turntable to be totally inaudible, unacceptably high, or anywhere between those extremes. There fore, various weighting systems for rumble measurements have been proposed and used. Weighting is a modification of the measurement to diminish the contribution of less-audible frequency components and to accentuate that of the more-audible frequencies in the final, single-valued rumble rating-expressed as a number of decibels below a reference level, making "higher" ratings preferable. Sometimes, as in the present example, rumble is specified as a signal-to-noise ratio (S/N or SNR). The two are identical except for their algebraic signs: S/N's are positive values and rumble ratings negative ones.

Throughout much of the world, the German DIN standards have been adopted for acoustic measurements, and most turntable rumble ratings, like those of the Hitachi HT-45, are expressed as "DIN-B" weighted values. Apart from its widespread use, the DIN-B rumble weighting has little to recommend it, since it virtually discards most of the actual rumble frequencies and thus produces unrealistically good numbers.

DIN-B rumble specifications are frequently around-75 dB. We prefer to use the Audible Rumble Loudness Level (ARLL) weighting proposed some years ago by CBS Laboratories. It is more realistic than DIN-B but also results in less impressive figures. We find that most good turntables measure around -60 dB with ARLL weighting, with a few as good as -65 dB.

A turntable whose rumble is largely at infrasonic frequencies, and thus not directly audible, can still degrade the reproduced sound by overdriving an amplifier output stage or driving a woofer cone beyond its linear limits-particularly when the amplifier's response extends down to d.c. (0 Hz), or nearly so, or if the speakers are ported or vented types. We find that most turntables have an unweighted rumble level of about-30 dB, with the best reaching -40 dB and only a few as poor as -25 dB. Some manufacturers' specifications include DIN-A as well as DIN-B rumble ratings.

The DIN-A standard is close to an un weighted measurement, although we have seen few turntables with published DIN-A rumble ratings as poor as our unweighted test measurements.

8.

The wow-and-flutter specification refers to the audible result of fluctuations of turntable speed, which cause a low-frequency frequency modulation of the reproduced program. These fluctuations usually result from pulsations of the motor torque and are related to the specific motor design. Wow is a slow up-and-down variation in turntable speed. Severe wow is heard as a distinct sliding of the musical pitch.

Flutter is a rapid variation in turntable speed. In the worst cases it is heard as a quivering, wavering, or "souring" of the musical pitch. The borderline between wow and flutter is vague, however, and they are usually specified and measured together.

Wow-and-flutter is measured by playing a test record carrying a steady 3,150-Hz signal (3,000 Hz in older test discs) and connecting the amplified cartridge output to a flutter meter, which is essentially an audio-frequency FM receiver with a meter that shows the modulation (in percent) of the 3,150-Hz carrier frequency when it is played back. (For example, a 3,000-Hz tone with 1 percent wow-and-flutter would change frequency over a ± 30-Hz range, from 2,930 to 3,030 Hz.) Wow-and-flutter is also a weighted measurement, since different rates of change have different degrees of audibility. Human hearing is most sensitive to wow-and-flutter when the flutter shifts occur at about a 4-Hz rate, and the test standards adopted by international bodies such as CCIR in Europe, and by the IEEE in this country, use a weighting curve that peaks at 4 Hz and reduces the contribution to the final reading of higher and lower rates. Most Japanese turntables, however, carry JIS weighted wow-and-flutter ratings, which yield lower (better) numbers than the others. One key difference between the JIS and the other systems is that it is a weighted-root-mean-square reading (usually abbreviated as wrms), whereas CCIR and IEEE readings are based on a quasi-peak measurement. The latter always produces less-attractive (higher) numbers, identifiable by a " ±" prefix.

Much of the wow-and-flutter we measure is ascribable to test-record warps or eccentricities, and it is unusual for us to measure values as low as 0.06 percent wrms or ± 0.08 percent weighted peak. Some turn tables carry lower ratings, such as the 0.025 percent (wrms) of the Hitachi HT-45, which was presumably measured with specially made lacquer test discs whose flatness and concentricity were carefully controlled.

Another common method with direct-drive turntables is to measure the wow-and-flutter within the motor's servo-control loop, which eliminates the need for a record, cartridge, or even tone arm. This can result in some impressively low readings, less than 0.01 percent in some cases, that may be a valid indication of the turntable's performance but cannot be compared with readings made in the conventional manner. Such wow-and-flutter readings can sometimes be identified by the appearance of "FG" (frequency generator) in the specification.

9.

The tonearm has the function of supporting the cartridge above the record, with the correct angular relationship to the radius of the disc, as the stylus traverses the spiral groove from the outer edge to the label area of the record. Most tonearm specifications deal with dimensions and design features. Some of these factors do have a bearing on the potential performance of the pickup system, but others (such as the shape of the arm tube) are irrelevant.

All else being equal, a straight arm (like that used in the HT-45) can obviously have lower mass than a bent arm, since it has less material in its tube (a straight line is still the shortest distance between two points, the points in this case being the arm's horizontal pivot and the cartridge's stylus). The "static balance" in the Hitachi specs indicates that the arm is initially balanced with the cartridge installed and that the counter weight is then offset to give the desired tracking force. Some arms are described as having "dynamic balance," which implies the use of a spring to provide downward force while the arm remains balanced. No particular advantage or disadvantage can be attributed to either design.

10.

The description of the Hitachi HT-45's headshell as a "plug-in type" suggests that it is not the old standard EIAJ pin-and-collar type shell. The photo confirms that it is a low-mass shell of the kind used on many recent record players.

11.

The tracking error is usually stated in the form used by Hitachi, as "±x degrees." A more meaningful specification would give the maximum error in degrees per inch (or centimeter) of radius, which has some relationship to the playback distortion. The Hitachi rating corresponds to a "worst-case" error of 0.8 degrees per inch at a 2.5-inch playing radius t perfectly satisfactory performance).

12.

The adjustable force range is actually not very important because it is almost always more than adequate to cover all required tracking forces.

13.

The specification for acceptable cartridge weight is important, especially in view of the very lightweight cartridges now available from several manufacturers. In this case, the minimum weight of 4 grams means that the arm will not balance with a cartridge weighing less than 3 grams. (Almost all super-lightweight cartridges are supplied with an additional weight to bring their total to more than 4 grams-mounting hardware adds a bit more.) These days, few cartridges weigh more than 9 grams, but one that did could not be used in this arm.

14.

The dimensions of a record player, like those of any other component, are important if you want to make sure that the unit will fit in an allotted space. Turntable dimensions are usually given with the cover lowered. Be sure also to allow sufficient clearance above the turntable so that he cover can be raised fully.

15.

The weight of a turntable is usually of minor importance except to indicate the overall solidity and massiveness of he unit (which has no necessary relation ship to its sound qualities). The weight can, however, affect the isolation of the record-playing system from floor vibrations or even from the acoustic output of the speakers, and thus it does affect the clarity of the overall sound. Turntable isolation is a complex subject, and no specifications deal with t quantitatively (there are no standards whatever for measuring it).