| Home | Audio mag. | Stereo Review mag. | High Fidelity mag. | AE/AA mag.

|

US: P.W. Mitchell

After last summer's CES was split into a two day trade show plus a two-day consumer show, journalists trying to cover all of the new products complained that a two-day trade show is too short. After evaluating comments from exhibitors and attendees, the EIA has decided that the best compromise will be to make the June 1993 CES a three day trade show. The public will be admitted on the fourth day (Sunday, June 6). The EIA also confirmed my suggestion (in August) that the published figure of 98,000 tickets collected did not correctly reflect the number of consumers who attended last June's show, because it contained a high percentage of repeats-the same people attending both Saturday and Sunday.

US: John A.

A poll die Academy for the Advancement of High-End Audio conducted of its members following the 1992 SCES, held in late May in Chicago, revealed that 68% of the 99 respondents considered the show not to have been a cost-effective promotional tool. The majority of respondents (80%) felt that just one CES a year would be sufficient, while slightly less than half attributed the poor attendance by the trade to have been due to the economy. The rest felt that it had been due to CES's decision to admit the public on the second two days of the show. Only 6% felt that the consumer days added anything to a show in decline, while 20% said that the trade/consumer format was the worst idea CES had come up with. 45% thought it was a barely workable format, while the 33% who thought it a good idea felt that attention was required to make it better. (72% of the respondents had exhibits that were open to consumers on the weekend of the show.) Although, as Peter Mitchell reports above, the 1993 SCES will allow consumers into the show on just the final day, the EIA is considering a five-day SCES for 1994, with three trade and two consumer days.

US: Robert H.

Hot on the heels of Sony's announcement of Super Bit Mapping (see elsewhere in this report for the latest details), Pacific Microsonics, Inc., a small Berkeley, California company, has revealed a digital audio encoding and decoding scheme that promises to be a quantum leap forward in CD sound quality.

The patent-pending process, called High Definition Compatible Digital (HDCD"), is the brainchild of recording engineer/de signer Keith Johnson and engineer Michael Pflaumer. The two designers, along with Michael Ritter, formed Pacific Microsonics to develop and market the new process.

HDCD is a sophisticated analog/digital converter and encoding process that produces a digital output compatible with all existing digital formats and hardware. CDs encoded with the process will reportedly realize significant audible improvements over conventional CDs, and are fully compatible with the CD format.

The second part of HDCD is an optional decoder that, when included in a digital/analog converter or CD player, realizes even greater sonic benefits than CDs made with the HDCD encoder alone, according to company President Michael Ritter. Note that the HDCD decoder is not required to play HDCD-encoded discs, which are filly compatible with all CD players and D/A converters. The company intends to manufacture professional HDCD encoders as well as license HDCD decoding technology to CD player and D/A-converter manufacturers.

The HDCD project began over five years ago when Keith Johnson and his partners were dissatisfied with the quality of digital audio when compared to the live microphone feed and his analog tape machine playback.

They developed innovative measurement techniques to discover and quantify the cause of the audible degradation introduced by digitizing an audio signal. The resulting HDCD process reportedly improves digital audio on two levels: 1) by avoiding introducing artifacts generated by conventional digital hardware, and 2) by encoding more information in the signal. Because some key patents were still pending at time of writing, the company wouldn't disclose technical details, but promised to reveal more information later.

The goal during HDCD development was to create a digital encoder/decoder system that sounded indistinguishable from Keith's original analog master tapes-a goal the company claims to have realized. The company also reports HDCD provides much better sound quality than Sony's Super Bit Mapping, even when played back without the optional HDCD decoder. Keith Johnson says that HDCD sounds closer to the microphone feed than any recording he's heard, even those made on his state-of-the-art, built-from scratch analog tape machine. If this proves true-and I have no reason to suspect it won't-HDCD will mark a turning point in digital audio sound quality.

The project has produced an engineering prototype HDCD encoder which has been used on the last four Reference Recordings projects? The company plans to have a commercially available HDCD encoder for sale by this time next year.

Ritter estimates that the HDCD decoder, when produced in large quantities, will cost the CD-player or D/A-converter manufacturer only a few dollars. A primary design goal was to put all the intelligence into the encoder side, making the decoder relatively simple and inexpensive. The first products to use the decoder will likely be high-end DIA converters, with the HDCD decoder implemented with DSP chips. Switching between conventional CDs and HDCD discs will be automatic.

I had an opportunity to see and hear the HDCD system during the most recent Reference Recordings direct-to-CD project (to be described next month). Although it was difficult to assess the technology or sonic results under the circumstances, I can report that the encoder is a reality. Moreover, the sheer amount of electronics required (including lots of DSP chips) attests to the system's sophistication. The encoder I saw took up a table top, but the production version will reportedly fit in two double rack-space boxes, one for the analog electronics and one for the digital.

Pacific Microsonics has invited JA and me to audition the HDCD process in early October and compare it to analog master tapes.

While I'm tremendously excited by HDCD's promise and potential, a definitive re port on its sonic merits must await a full audition.

These are exciting times in digital audio.

1. Pacific Microsonics is not affiliated with Reference Recordings, but because Keith Johnson is Reference's recording engineer and a designer of HDCD, it is natural that he would use the process first on Reference releases.

The first four titles encoded with HDCD are: Testament, a selection of choral music by 20th-century American composers performed by the Turtle Creek Choral and the Dallas Wind Symphony; Dick Hyman !nays Duke Ellington, recorded direct-to-CD; The Oxnard Sessions, Volume 11 by pianist Mike Garson; and Trittico, a mixed program of works for wind band conducted by Frederick Fennell. The first two will be available in fall 1992, with the latter two scheduled for early 1993 release.

While these discs will reportedly provide better sound than conventionally encoded CDs, remember that they don't rep resent HDCD's capability; the new process's sonic potential is realized only when played back through the HDCD decoder.

US: John A.

With the launch of MD and DCC imminent as you read this, both media only able to work by throwing away data that psycho acoustic experiments indicate might be unnecessary, it was ironic to read in September issues of Science News and The Economist of new methods of storing data that would obviate the need for such "lossy" data compression. The Atomic Force Microscope (AFM), developed by IBM, and AT&T's Near-field Scanning Optical Microscope (NSOM) can both store data with a vastly more efficient packing density than the CD's pits, though at present that data cannot be read fast enough to make real-time digital audio playback possible Within a few years, however, it most probably will be. Which would make it doubly ironic if, by then, the CD had been replaced by the inferior MD or DCC.

Japan: P. W. Mitchell

Sony's first MiniDisc products go on sale in Tokyo during the first week of November- see Robert H.'s full report later in this issue-and will begin to arrive in US stores a few weeks later. The first models include a play-only portable at a list price of $550, a portable recorder at $750, and a car player for $980. Japanese buyers will be able to choose from around 500 prerecorded MD titles by year's end, 190 of them on Sony owned labels. Two-thirds of the 500 are by international (mainly American) performers; the rest will have performances by Japanese artists for domestic sale. Sony's Digital Audio Disc Corp. plant in Indiana is already turning out recorded MDs at the rate of a half-million per month for the North American market, while Sony and Denon plants in Japan are producing MDs at a similar rate. Contrary to previous reports, the first MDs will be priced equal to CDs.

Since the analog cassette has never been as popular in Japan as in the US, Europe, and the third world, the MD is expected to outsell the DCC in the domestic Japanese market.

Consequently Matsushita (Technics/Panasonic) has signed up for a license to pro duce MD equipment, in a cross-licensing deal with Sony through which companies licensed to manufacture either MD or DCC will gain access to patents on both technologies.

US: Carl B.

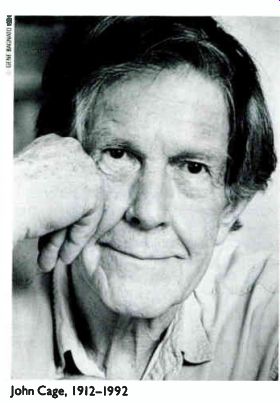

Composer John Cage liked to think of him self as an inventor of music. The conceit is apt, considering that Cage created more than just orderings of tones; in many cases, he created the instruments on which to play them as well. When the inventor of the prepared piano died in New York of a stroke on August 12, 1992, just a few weeks shy of his 80th birthday, the 20th century lost one of its most provocative, controversial and, ultimately perhaps, influential composers.

Cage was born in Los Angeles on September 5, 1912 and studied with such modern masters as Varèse, Schoenberg, and Cowell.

When Schoenberg made his now famous remark to the young student that he possessed no talent for harmony and would eventually reach a wall as a composer, Cage responded in the spirit that would characterize his entire body of work: "I shall beat my head against that wall." And beat he did. His often radical concepts of indeterminacy, chance, and silence wielded considerable influence over European and American composers. His most well-known works included the pieces for prepared piano, Music For Toy Piano (1960), Radio Music for 1-8 Radios, and Imaginary Landscape NoS for Electronic Tape. His most provocative composition, 4'33", consisted of the ambient sounds in a room as a pianist sits silently at the instrument and does not play for the piece's 4 minutes and 33 seconds. Equally significant, however, were such lesser-known works as the sublime String Quartet in Four Parts (1949-50), in which Cage offered an alter native to conventional harmonic concepts with his own brand of monophonic harmony; he called the concept "a line in rhythm space." Cage was a brilliant lecturer and writer, and was considered to be an expert on mushrooms as well. His book, Silence, is thought to be one of the major tomes on John Cage, 1912-1992 modern music, along with Harry Partch's Genesis of a Music and a few others.

Unlike most composers, Cage was not so much interested in creating a personal body of work as in the investigation of methods, sources, and concepts. His interest in Zen and the I Ching gave his music a philosophical bent, and his good-natured humanity always infused his creations with a whimsical sense of awe and discovery. Humor and surprise were often balanced by the most probing tortures in ways that precluded any hint of pomposity or posturing.

John Cage embodied the oft-discussed but seldom realized American ideal: he was a genuine original. His unique independence placed great demands on performers and audiences alike. The results were often compelling, sometimes maddening, but always new, and even his detractors did not begrudge him his curiosity and intellectual persistence.

The avant-garde is much the poorer for his passing.

Japan: Robert H.

In last August's issue of Audiophile, Corey G. and I reported on a demonstration of Sony's Super Bit Mapping (SBM), the CD mastering process that claims to achieve nearly 20-bit resolution from the 16-bit CD-without changing the CD format or playback hardware Corey and I-along with just about everyone else who heard the demonstration-were very impressed by the improvement SBM appeared to make in CD sound? During a Sony-sponsored press trip to Japan in August, I had an opportunity to hear SBM at greater length at Sony's Tokyo recording studios. More importantly, the Tokyo auditioning made it possible to compare SBM-processed 16-bit to a 20-bit digital master. A Sony open-reel digital recorder that had been specially modified to record 20-bit data was the signal source The machine's 20 bit digital output drove the SBM box, which would either pass the 20-bit data intact, per form SBM processing, or truncate the 20 bit words to 16-bit. It was thus possible to hear full 20-bit digital audio, 16-bit after SBM processing as would appear on SBM CDs, or truncated 16-bit. The only option not available for auditioning was redithered 16-bit, which would have made the listening more informative. Redithered 16-bit is vastly better than truncated 16-bit; truncation is virtually never used anymore.

As the front-panel switch on the SBM box was thrown, a TV monitor displayed the switch status: 20-bit, SBM, or 16-bit. The truncated 16-bit version was immediately identifiable: the sound was coarse, hard, lacking depth, had poor image focus, and imposed the familiar glare in the upper-mids and treble that can make digital fatiguing.

The 20-bit version was much sweeter, more spacious, better focused, had a sense of ease, and provided greater resolution of fine detail.

The SBM-processed signal was remarkably close to the 20-bit source. Where the 16-bit truncated signal was obvious, I couldn't always distinguish between 20-bit and SBM without looking at the TV monitor. There was, however, some difference: the SBM version didn't have quite the space, smoothness, and resolution of the 20-bit, but it was very close, particularly when compared with

[2. See the beginning of this month's "Industry Update" for a report ors another system that may improve CD sound quality, and elsewhere for Richard Schneider's impressions of Super Bit Mapping as applied to Sony Music's classical reissues.]

truncated 16-bit. While I was impressed by SBM from the June SCES demonstration, I was even more impressed after hearing how close SBM came to full 20-bit digital audio.

Nevertheless, I would have liked to have heard a properly dithered 16-bit signal. One conclusion that could be drawn from the listening session is that truncation of digital audio is horrendously bad-a fact the world is belatedly learning.

The other comparison missing from the demonstration was with the original analog source tape. How close does 20-bit come to analog? And more importantly, how close will 16-bit CDs mastered with SBM come to the original analog reference? I'll have an opportunity to hear these comparisons first hand: Sony Classical has invited me to their New York studios to transfer one of our own original analog master tapes to 20-bit digital, then process the signal through SBM. This is the most revealing of all tests; the analog reference will reveal degradation imposed by the conversion to digital and the differences between 20-bit and SBM. [3]

We may use SBM on Audiophile’s next CD (pianist Robert Silverman performing works by Schumann and Schubert) and include both conventional and SBM versions of one track on the CD release' Of course, the recording will also be available in pure analog form on vinyl, made from the original analog master tape.

US: Richard S.

Sony Classical has embarked upon its most ambitious and comprehensive series of reissue projects since acquiring the ranch once known as Columbia Records. The first of these projects, designated the Leonard Bern stein Royal Edition, will eventually comprise 199 mid-priced titles, all taken from stereo

--- 3 Doug Sax, co-founder of Sheffield Lab and an outspoken critic of digital audio, told me years ago that, any time I record, it is essential to roll both analog and digital machines. Without the analog reference, he counseled, one becomes inured to digital sonic limitations and forgets analog's many virtues.

4. This is provided we can borrow the SBM box for the session, feeding it with 20-bit data from the Manley 20-bit A/13 and outputting the 16-bit data to a DAT machine. Alternately, we could record on a 20-bit storage format (such as the Sonic Solutions Sonic System and hard disk drive) and perform SBM later. Both plans are tentative.

--------

recordings from the 1950s through the '70s, nearly all with the New York Philharmonic, standard repertoire emphasized.

The initial release in June revealed a systematic if less than imaginative approach- alphabetical order by composer. So we have Beethoven's nine symphonies, which have been available on CD for some time, but we also have the CD debut of a Bartók concerto collection featuring Phillipe Entremont, Gold and Fisdale, and Isaac Stern. Parenthetically, Sony has included Bernstein's celebrated 1956 lecture, "How a Great Symphony Was Written:' with the Beethoven 5th on a sep arate budget-priced CD. The lecture is in mono, and selectable by track and channel in English, German, French, or Italian. (Sony is still working on digital conversion schemes for Oil'n'Vinegar and Thousand Island.) Due to its perception of the global nature of today's record business, Sony is marketing this series under the Royal rubric, utilizing the watercolor landscapes of Prince Charles as album covers. Art criticism aside, the sheer reduction in size of cover art from LP to CD gives these releases a generic sameness of appearance as more titles in the series are released each month with seemingly exponential determination. A treasure such as Bernstein's unforgettable performance of Bloch's Sacred Service runs the risk of being lost in the shuffle as recession-cautious collectors experience sensory overload at the growing stacks of white boxes with their diminutive, nearly indistinguishable aquarelles.

But behind what appears to be yet another recycling of old stuff in inappropriate pack aging is the intriguing story of Sony's recently developed process of Super Bit Mapping, which received substantial cover age from Corey G. and Robert H. in the August 1992 issue. Common to both reports was the distinct impression that SBM's public debut would occur in the future in a premium-priced series of Legacy Mastersound CDs utilizing SBM, in artfully attractive oversized packages that space squeezed retailers will love to hate.

The fact is, SBM has been an element of nearly every Sony full- and mid-price release since January 1992, in new, fully digital recordings as well as reissues of analog material. This does not apply to the budget-price Essential Classic Series, though many of these tides have nonetheless benefited from the 20-bit treatment, as well as careful remastering.

If you have Kathleen Battle's and Winton Marsalis's Baroque Duets, Emmanuel Ax's Brahms Variations, Mehta Conducts Wagner, or any of the titles which comprise the Royal Edition, you've already got SBM. Sony has taken a peculiar approach to acquainting the public with the fact that it's been using SBM all year. Rather than announce the process as it was brought into use, they held a news conference for the audio press at CES to herald its future launch.

Meanwhile, over the course of the summer, Sony invited New York-based music and audio journalists to its studios for an inside look at the remastering process used in the Royal Edition.

I was under the impression that I would be attending an actual remastering, such as one I attended when Chesky made its own cutting of the Reiner/CSO Lieutenant Kije at RCA in 1987. Or, at the very least, I would be witnessing a remastering demonstration, as hosted by Philips with Wilma Cozart and Mercury Living Presence in 1990. Nothing so elaborate. Called to Sony's New York facility late on a weekday after noon in July and ushered into a studio furnished with a pair of B&W 801 Matrix 3 loudspeakers, I was asked to listen to some remastered Haydn symphonies on finished production masters. The producers and team members are musically literate; scores of the works being prepared were on hand. Bern stein's Haydn sounded very powerful and full, in contrast to the period-instrument approach this music gets today. The overall level was higher than I like it. But there was no frame of reference, such as the raw un processed studio masters from which this production was derived (a hallmark of the Mercury demonstration). I was impressed by the fullness of the sound and the overall frequency balance, which had been problems with Columbia LPs of the period. But I was disturbed by the fades to total silence between movements, as well as the unmistakable sound of "tails" merrily ringing out the final notes.

Guiding me through my Sony experience were Alan Penchansky, a public-relations liaison, and David Smith, a Sony engineer.

They explained that some of their producers are very fussy about extraneous stage noise, and that the members of the NYP were so incorrigibly noisy that these producers feel that any means must be pursued to suppress all evidence of their sloppy and unprofessional behavior. Moreover, I was told that some of the sessions which had taken place in dry, unforgiving studios-rather than in concert halls, ballrooms, or other large spaces--would have a bit of ambience added via a light Lexicon program. Such added post production confuses the issue of SBM as a single breakthrough in sound quality.

Penchansky made a point of the value of remixing the original balances for 1990s CDs as opposed to 1960s LPs, but I'm afraid he misses a point. Many of these masters are on three channels. The most one can do is establish a left-right balance, and find a rational proportion for the center channel which will satisfy presence as well as depth. Beyond that, the mix was established at the session.

Cases in point: Anyone who has seen the DG video "The Making of West Side Story" has seen living proof that, when it came to mix, Bernstein rode roughshod over production staff in order to achieve clarity of instrumental line, without regard to realistic concert-hall proportion. And in the scherzando section of the second movement of the Bartók Violin Concerto 2 with Isaac Stern, a rhythmic figure is tossed back and forth several times between timpani and open side drum. The passage is quiet, lightly scored, The ROYAL SIDEBAR

A Studer A820 open-reel recorder, customized for low speed and low tension in order to be gentle to old, fragile tapes, feeds to a Cello Audio Suite preamplifier, which in turn feeds the Data Conversion Systems DCA 900S (same as used by Wilma Cozart) to an Ibis four-channel mixer (most masters are three-channel). The Ibis feeds a custom-made Sony 20 bit recorder whose signal is routed to the Super Bit Mapping Processor, which then feeds into four Sony PCM-1630s. Four production masters are so made for CD mastering worldwide. There are no dones.

Sony plans to eventually convert its entire catalog to SBM remastered editions.

Work is monitored on B&W 801 Matrix 3s powered by paieect Cello Dyer 3N amplifiers.

-Richard S.

insisted that the percussion be heavily spot miked and brought up in the left-channel mix, so that the deaf couldn't miss it. Thirty years later, there is nothing post-production can do to fix lapses in judgment of this type.

Over the course of the summer, I managed to acquire a considerable number of Royal Edition releases. By and large, they make a favorable impression, with qualifications. In particular, items in the Bartók Concerto collection seem to have a bit more ambience than they should, and an enormous tail on the Rhapsody No.1, a favorite of mine, which Bernstein and Stern play to a greater fare thee-well than any of the native Hungarians have managed to do.

Perhaps more instructive than anything shown to me at Sony was my own ability to A/B (or MB/CID) four versions of the same recording: the Columbia LP (MS 6251), the 1986 CD (MK 42263), the 1991 3-CD Bernstein Portrait: Theater Works, Voll (SM3K 47154), and, finally, the Royal Edition (SMIC 47529) of Bernstein's NYP recording of Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, taped at Manhattan Center in March 1961.

The 1970s vinyl pressing suffered from the shrill high-boost EQ characteristic of Columbia product of that period. Each CD version (each remastered by a different crew) offered evolutionary layers of improvement.

MK 42263 was correctly EQ'd, but was out done for color and space by SM3K 47154, which was remastered with 20-bit technology, but not SBM. Best of all was the new Royal Edition with SBM. Beyond dimensional and timbral considerations, I was impressed by the delicacy of the writing for Latin drums, which in the "Saturday Night Dance" music no longer seemed just loud.

It was impossible to appreciate the subtlety and skill with which these parts were played.

Dances and its original flip side, Suite from On the Waterfront, were two of Bemstein's best sessions: great studio performances, excellent recordings in which he didn't inflict notice able damage on the mixes, and for which the sound of Manhattan Center provided enough of its own ambience to keep the synthesizers at bay.

It would seem that though The Royal Edition is a mixed bag sonically, SBM actually is the breakthrough it's touted to be. Sony should exercise more restraint in its post tiptoe through their own tapes without leaving footprints, as BMG's Nat Joluison is able to do, it would be better for them to adopt the fanatical purist practices of Mercury's Wilma Cozart. Look at it this way, Sony: Only audiophiles buy recordings for sound, and they like honest sound. The average con sumer shops for artist and repertoire, and will accept a very wide range of sound if it's not obviously horrible. Since honest sounds good, why not let it go at that? US: John A. If audiophiles are crazier than the general population, and Audiophile’s crazier than audiophiles, and stereophlles who own tube gear crazier than the rest of us, then who could possibly be crazier? People into antique tube gear, that's who-those whose eyes light up at the thought of single-ended 6W amplifier designs, using behemoth transmit ting tubes with white-hot, directly heated cathodes, and driving horn speakers.

Sound Practices, a new quarterly magazine edited and published by one Joe Roberts, is aimed fairly and squarely at these fanatics, its first issue featuring an article on an amplifier design featuring the 300B tube, an article on horns, the data sheet on the 8"-tall 845 tube, and the schematic of Western Electric's No.91-A amplifier from the '30s. Joe Roberts promises that subsequent issues will feature amplifiers that do offer more than 10W out put. Sound Practices, Box 19302, Alexandria, VA 22320. Tel./Fax: (703) 836-4382. A year's subscription costs $16.

And if you're into things thermionic, don't forget Glass Audio, now in its fourth year of publication. A year's subscription costs $20; two years, $35. Glass Audio, P.O. Box 176, Peterborough, NH 03458-0176. Tel: (603) 924-9464. Fax: (603) 924-9467. US: Peter W. Mitchell In September's "Industry Update," the address I listed for subscriptions to Hi-Fi Choice was actually for UK subscribers only.

Non-UK subscribers should send address and credit-card details to Hi-Fi Choice Subscriptions, Chadwickham House, 19 Bolsover Street, London WlE 4UZ, England.

In October's "As We See It" I discussed Snell's CES demonstration of the Sig-Tech AEC-1000 filter and concluded that digital

----

signal processing for room-acoustics correction is the single most important advance in audio since the CD-perhaps since the advent of stereo. Evidently others thought so too. Because of enthusiastic reactions to this and other demonstrations, Cambridge Signal Technologies has decided to develop a consumer version of the $10,000 pro-audio SigTech processor. It will be priced under $5000 when it is introduced next spring. By then the first processors from the MusicSoft consortium (Snell Digital and Audio Alchemy) may already be in stores. Another implementation of this idea has been developed independently in England by B&W with Michael Gerzon as consultant. The B&W product will be a complete digital preamplifier, with inputs for several digital sources (CD, DAT, DCC, et a/) together with the DSP standing-wave correction filter. Evidently 1993 will be The Year of DSP. At last summer's CES I carried a CD-R disc on which E. Brad Meyer had copied favorite speaker-evaluation tracks from several CDs, plus portions of some of the recordings that he and I have engineered (separately and together). When I visited the Swan's Speakers room to hear the Cygnus speaker, one of the recordings I played was a movement of Brahms's Alto Rhapsody, re corded in concert. When this achingly beautiful music ended, everyone in the room was weeping. Of course we all were conscious that Swan's designer and good friend Jim Bock had succumbed to lung cancer just three weeks earlier. But I couldn't help recalling Robert H.'s remark that he judges products not only by the quality of the sound itself but also by how well the emotional power of music is conveyed. Perhaps the Swan's Cygnus speaker really is one of those products that communicate musical expression with special power.

Japan: Robert H.

Sony Corporation showed off the technology behind their new MiniDisc format for the US press recently in Tokyo. Envisaged as the replacement for the analog cassette, the 2.5" (64mm) MiniDisc (MD) can store up to 74 minutes of "near CD quality" digital audio and looks like a miniature CD in a plastic caddy. In fact, the MD looks surprisingly similar to the 3.5" computer diskette (but much smaller), with a sliding media protection cover and center hole. The discs can be either prerecorded (made from polycarbonate just like CDs) or recordable/erasable using magneto-optical technology. One machine will play both types of discs.

Sony reiterated their commitment to launch MiniDisc in Japan on the first of November, and to introduce MD to the US market "before Christmas." Sony President Norio Ohga said he saw "no obstacles to introduction" by the scheduled launch dates.

Philips's competing Digital Compact Cassette (Dcc) has suffered two launch delays (with another one rumored), making it likely that the two consumer digital recording for mats will appear in the marketplace simultaneously.

How did it happen that Sony and Philips, partners in creating the enormously success ful Compact Disc, are now about to battle it out with competing formats? According to Sony, they were three years into development of MD in 1989 when Philips showed them DCC and asked Sony to become a partner in the format. Sony then showed Philips the MiniDisc, and tried to convince them to abandon the tape-based DCC in favor of the optical disc-based MD. The two sides couldn't agree, creating a situation in which consumer confusion may kill both formats.

MD's MARKET POSITION: THE POTENTIAL THREAT TO CD

As a replacement for the analog cassette, MD is, I believe, a great advance-both in sound quality and convenience. Even with its 5:1 data-compression scheme, MD's sound is probably far superior to that of the analog cassette, which suffers from high-frequency rolloff poor stereo imaging, speed instability, tape hiss, and mechanical problems.

I am concerned, however, that one-or both-of the two new recordable digital formats will actually kill CD. The mass market consumer may look at MD and CD as merely small and large digital audio discs-and the small one is recordable [and cute.- Ed.]. Sony's reaffirmation of their commitment to CD and the development of Super Bit Mapping that improves CD sound quality are heartening, but the consumer (and retailer) will have the final say.5 The possibility that music will be available only on media that require data compression is a chilling scenario. It would be ironic-and tragic-if, in ten years, uncompressed CDs were available only from specialty high-end labels, much the way currently-produced LPs are now distributed to audiophiles.

I voiced these concerns to Mr. Ohga during a question-and-answer session. He insisted that Sony has "a lot invested in CD," "is not about to abandon" the format, and they are "committed to CD as the state-of the-art playback [medium]." MD HARDWARE Sony had only limited demonstrations of MD hardware for the visiting journalists.

This was surprising considering the launch date was only 60 days away. We did see, how ever, a fully functional car MD player. The unit performed flawlessly, even when picked up, shaken, and dropped on a table. An MD recorder was shown, but this was a large unit, not the small portable package shown in mockup form at CES two months earlier.

The recorder was marked "For Professional Use Only," presumably to avoid any copy right infringement concerns. When we asked to see portable playback units-presumably the primary MD application-we were told that Sony was "not in a position to reveal actual product" during our visit.

6. MD TECHNOLOGY

The MiniDisc is based on four technologies either invented by Sony or refined by them to become practical in an inexpensive consumer product. These technologies are: 1) a 5:1 data compression scheme called ATRAC (Adaptive TRansform Acoustic Coding); 2) magneto-optical (MO) record/playback with direct "overwrite" capability; 3) a dual function laser pickup that will play both prerecorded polycarbonate discs and MO 5 Super Bit Mapping is a method of achieving near 20-bit resolution from 16-bit CDs. See "Industry Update" in this issue and in Vol.15 No.8. Another process that may improve CD sound, called HDCD, is also described in this issue's "Industry Update"

6 At dinner one night. I sat across from the project manager for personal portable development. I said to him, You must be very busy with the launch less than two months away." The knowing look on his face confirmed that they were burning the midnight oil. He assured me, however, that the product would be fully ready for the launch.

recordable discs; and 4) a "shock-resistant memory" that provides skip-free playback even when shaken violently in portable applications. The MD is so packed with new technology that Sony has been granted or has pending nearly 300 MD-related patents.

ATRAC Data Compression: To provide 74 minutes of playing time on a 2.5" disc (and make the entire format possible), Sony developed the ATRAC data-compression scheme.

ATRAC (Adaptive TRansform Acoustic Coding) reduces the storage requirements of the medium by 80% by more efficient coding techniques as well as by throwing out musical information judged to be inaudible.

As with all "lossy" data-compression systems, ATRAC relies on human hearing models to decide which information is audible and which isn't. The large quantization errors produced by low-bit-rate encoding are theoretically masked (hidden) by the correctly coded portions of the signal. With these techniques, a stereo digital audio signal that consumes 1.41 million bits per second with PCM encoding (as on a CD) requires only 256 kilobits per second (kb/s) after ATRAC encoding.

This compression rate is greater than Philip's PASC encoding developed for DCC-PASC's data rate is 384kb/s for a stereo signal. ATRAC, however, differs from PASC in many areas. First, ATRAC relies on a different human hearing masking model and uses a completely different coding scheme. Presumably, ATRAC takes advantage of the higher ambient noise levels present outdoors and in cars, where MD is most likely to be used.

Moreover, ATRAC is fundamentally different from PASC in that it uses nonuniform frequency and time splitting. In these regards, ATRAC is very similar to ASPEC, a low-bit rate coding scheme developed by AT&T Indeed, Sony admitted they may have to pay royalties on MD: AT&T owns key patents on some of the techniques used in ATRAC. ATRAC operates in the digital domain on normal, 16-bit PCM-encoded digital audio.

The ATRAC encoder divides the PCM digital data into time segments varying between 1.45 ms and 11.6 ms. The audio signal's transient characteristics determine the time window length; the steeper the waveform, the shorter the time block. This technique reportedly results in superior time-domain resolution. Next, the time blocks are split in the frequency domain into 25 bands of non uniform bandwidth. This band-splitting is based on the critical band principles of human hearing. At low frequencies, the bands are much narrower-80Hz wide at the 50Hz band-than at high frequencies. The widest band is 2.5 kHz, centered on the 13.5kHz subband. For comparison, PASC splits the audio band into 32 equal-width subbands.

The ATRAC encoder then performs Fourier transform analysis on the digital wave form in each segment. Fourier transform analysis converts a complex waveform into its individual pure sinewave components.

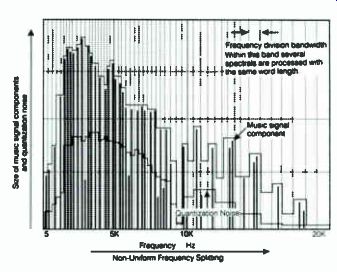

The amplitude changes in each band are analyzed as single frequency components, and bits are allocated based on the signal's spectral distribution, amplitude (taking into account the threshold of hearing), and masking effects. Because high-frequency components have been removed from the lower-frequency bands, fewer bits are required to encode frequency information. Fig.1 shows ATRAC's nonuniform frequency splitting, and how quantization noise is distributed so that it is likely to be masked by the audio signal.

During playback, the decoder reassembles the many frequency components and reconstructs the time segments into 16-bit PCM audio data for conversion by conventional 16-bit D/A converters. The ATRAC decoder output can also be formatted into S/PDIF data for connection to an outboard D/A converter. It will also be possible to drive an MD recorder with the S/PDIF output of a CD transport; the MD's 74-minute playing time was no accident.

Unlike Philips's position on PASC encoding, Sony admits that an ATRAC- compressed signal is of lower quality than an uncompressed signal from CD. According to Sony, "some people will hear" the difference ATRAC encoding produces, but this is limited to "2% to 5% of the population." Although I feel that data compression is a step backward in audio's progress, Sony should be commended for positioning MD as a personal portable format (where fidelity is less critical than in the home), and their emphasis that uncompressed CD audio is superior.

Philips maintains that the PASC encoding Fr Frequency Hz Ne,UndelmRequamvS0..9

Fig. 1 Sony MD, ATRAC's non-uniform frequency splitting and distribution of quantization noise (courtesy Sony). used in DCC is "inaudible" and "transparent." Indeed, Philips even claims that, with an 18-bit master tape source, DCC sound quality is superior to CD playback.

Multiple-generation copies of an MD will suffer from what the data-compression gurus call "cumulative impairment"; copies from one compressed medium to another start to sound very bad very quickly. Despite the generation loss when copying from one MD machine to another, Sony has incorporated the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS) in the MD format. This scheme, now used in DAT recorders, permits one digital-to-digital copy but prohibits second generation digital-to-digital transfers. I suspect SCMS was included more to placate record companies than for any practical necessity.

MD uses the same CIRC error-correction code as CD. Because of ATRAC data compression, however, burst errors from MD are potentially more audible than the same length error from CD. Magneto-Optical Technology with Overwrite Capability: MD's record/erase aspects are based on magneto-optical (MO) technology, first used in the computer industry for data storage. Computer MO drives are large and expensive, hardly the technology one would expect to find in the portable MD. Sony, however, has vastly refined MO to make it practical in a small, inexpensive consumer product like the MD. As its name implies, magneto-optical is a combination of magnetic and optical techniques.

----

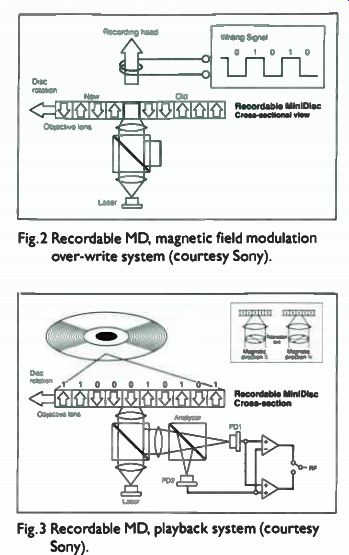

Fig. 2 Recordable MD, magnetic field modulation over-write system (courtesy Sony). Fig.3 Recordable MD, playback system (courtesy Sony).

----

The process is based on two phenomena: 1) a magnetic material's coercivity (its resistance to changing magnetic orientation) drops when heated; and 2) laser light's polarization is rotated when exposed to a magnetic field. Here's how it works.

A laser with a very small spot size (1µm) is focused on a spinning disc coated with magnetic particles standing on end-like trees in a forest instead of lying flat as on most magnetic media. The laser heats the magnetic particles to the "Curie point," the temperature threshold beyond which it takes very little energy to change their magnetization.

A magnetic head, located on the opposite side of the disc from the laser source, is driven by the signal we wish to record. The disc's rotation displaces the area to be recorded, at which point the magnetic material takes on the polarity of the applied magnetic force By heating a small area of the disc with a laser, a very weak magnetic field can change the magnetic particles' orientation. Moreover, only the tiny spot heated by the laser is affected by the head's magnetic field. Note that the laser doesn't actually transfer information to the medium: it merely heats it to make it more easily magnetized. This technique, shown in fig. 2, makes it possible to record extraordinarily tiny magnetic features.

During playback, the laser is reflected from the spinning disc where it is exposed to the magnetic fields recorded on the disc. These magnetic fields rotate the laser beam's polarization, a phenomenon called the "Kerr Effect."7 The reflected beam, now comprising two alternating polarizations as a result of the north-south and south-north magnetic fields, is passed through a polarizing beam splitter and to photodetectors. The signals from the photodetectors thus represent the north-south and south-north magnetic fields on the disc, which in turn represent the original binary data applied to the magnetic recording head. The photodetectors also generate tracking and focus servo signals. MD playback is shown in fig.3.

Rather than having one magnetic orientation (and thus one polarization plane) rep resent binary "1" and the other orientation represent binary "or MD uses Eight-to Fourteen Modulation (EFM), the same encoding scheme used in the Compact Disc.

EFM encoding creates a specific pattern of ones and zeros that results in nine discrete lengths of magnetic orientation on the MD disc. These patterns correspond exactly to the nine discrete pit or land lengths on a CD. Just as a CD's pit edge (either leading or trailing) represents binary "1" and all other surfaces (pit bottom or land) represent binary "0," a change in the media's magnetic orientation represents binary "1" and no change represents binary "0." Think of one magnetic orientation as a pit, the other orientation as land, with the information encoded in the lengths between transitions.

Sony has refined and miniaturized MO technology to the point that it can be made 7 To understand light polarization and polarizing filters, think of a string stretched through a grating with vertical bars. If we move one end of the string up and down, imparting a vertical wave motion to it, the vertically polarized wave will pass through the grating unimpeded. If we move the string back and forth, the grating will not let the wave through. The situation is reversed with horizontal bars; back-and-forth wave motion will pass, but not vertical motion.

Similarly, a polarizing filter allows only one direction of polarization to pass; it is opaque to all light except that polarized in a certain plane. If you've ever looked through two polarizing lenses simultaneously, you may have noted that by rotating one of the lenses, the two layers become alternately translucent and opaque. Although normal light is not polarized (as is laser light), the first polarizing filter allows only one plane to pass. When the second filter is rotated so that it allows that same plane to pass, the two layers become transparent, smaller, lighter, cheaper, and with low power consumption-all requirements of a personal portable format. These refinements include the "overwrite" technique that permits direct recording over a previously recorded disc without the need for either a second erase laser or a two-cycle erase/record process.

Computer MO recorders use a second, higher-powered laser for erasure or require a separate erase step before rerecording new data.

Another Sony breakthrough in MO technology is MD's very-low-coercivity magnetic material, allowing magnetization with a very weak field. This reduces the size and power requirements of the magnetic head, reducing weight, cost, and power consumption. The magnetic material is called Terbium Ferrite Cobalt and has a coercivity of 80 Oersteds, about one-third the coercivity required in conventional MO media.

Power consumption is a significant factor in MD's acceptance. Although Sony claims two hours from a set of batteries in a play back-only portable, they didn't disclose any estimates of MD recorder battery life.

Recorders will consume much more power; the recording laser and current-driven magnetic head are both power-hungry devices.

Shock-Resistant Memory: A primary objection to optical discs in personal port able applications is interruption of the music caused by shock or vibration. Sony has solved this problem in MD with a "shock resistant memory!' The shock-resistant memory is based on the fact that data can be read from the disc five times faster than it is input to the ATRAC decoder. This is because one second's worth of ATRAC-compressed data represents five seconds of decompressed audio. This differential is exploited by putting a large buffer (1 Mbit, equal to three seconds of music) between the optical pickup and the ATRAC decoder. The buffer is filled with data from the disc in chunks, just often enough to keep the buffer nearly full.

When the laser pickup is shaken off the track, data are continuously clocked out of the buffer, giving the pickup time to return to the track. Laser pickup mistracking is thus completely transparent to the listener. An address system, similar to that used in CD ROM, identifies data sections so that the pickup returns to the correct disc position.

This technique is analogous to a bucket of water with a small hole in the bottom that is periodically filled by another bucket of water. The water flows slowly and continuously from the hole despite the periodic bursts refilling the bucket.

MD LISTENING COMPARISONS

Of particular interest to me were the listening sessions in which we compared CD and MD sound. The output from a CD player could be auditioned directly or switched through MD's ATRAC data-compression scheme (see later). It was thus possible to hear the same music in linear 16-bit PCM audio and after ATRAC encoding/decoding, which reduces to one fifth the number of bits representing the audio signal. We were encouraged to bring our own CDs for the comparisons.

Although this listening session was much more extensive than the June CES demonstration, it was far from adequate to fully explore the effects of ATRAC. Moreover, the switching between CD and ATRAC was far too fast-sometimes after just five seconds.

I would have preferred to hear a piece of music in its entirety from CD, then ATRAC processed, then from CD again. This type of listening is much more revealing than rapid switching. I was, however, able to draw several broad generalizations about the audible effects of ATRAC. These impressions should be considered very preliminary; a full assessment awaits extended auditioning through a reference playback system.

My overall impressions of ATRAC were largely favorable-considering the fact that the data rate was just 20% of that of 16-bit linear PCM as found on CD. Although the degradation imposed was virtually always audible, the degree of impairment varied greatly with the source signal's characteristics. On a pop recording Sony had selected, the upper midrange and treble region became drier, "whiter," and took on a more sterile characteristic. The cymbals and hi-hat, which sounded mechanical to begin with, sounded more so when subjected to ATRAC encoding/decoding. This was accompanied by a reduction in "air" in the top octave, with the presentation closing in slightly and suffering a reduction in transparency. ATRAC also tended to overlay instrumental textures with a layer of grain and coarseness. I also noticed a reduction in pace and rhythm, as though the music had slowed down marginally. Of course, the tempo couldn't change, but the subjective effect was a lessening of the music's rhythmic tension. Finally, ATRAC tended to make the bass a little woollier.

For my musical selection, I chose Mike Garson's The Oxnard Sessions, Volume One (Reference Recordings RR-37CD). I thought this recording's superb sense of space would reveal ATRAC's effect on soundstaging and resolution of spatial information. Unfortunately, the studio's playback system didn't reveal the recording's depth and size with or without ATRAC, making it impossible to determine the encoder's potential impairment of spatial cues. What the recording did reveal, however, was that signals that were liquid, smooth, and lacking hardness-a description of The Oxnard Sessions-largely retained these qualities through the encoding/decoding cycle. Textures that were hashy, grainy, and strident before ATRAC became more so when subjected to ATRAC encoding/decoding. The grainier the input to the ATRAC encoder, the greater the coarseness ATRAC appeared to add to the signal.

Similarly, instruments that were forward and dry also seemed to be the most affected by ATRAC. One journalist had brought a disc with closely miked glockenspiel and bells, signals that were clearly and significantly impaired by ATRAC. A track containing a positive-going impulse every 128 samples sounded much like a tone without ATRAC; with the encoder/decoder switched in, it sounded more like a buzz saw. This is to be expected: low-bit-rate encoders work only when broad-band signals can mask the large quantization error created by encoding the signal with so few bits.

I must reiterate that this listening session was by no means comprehensive: a full assessment of ATRAC requires long-term listening over a huge range of music and under varying conditions.

Although Mini-Disc's sound quality is obviously inferior to that from CD, it is likely to be better than analog cassette. Only extended listening will reveal whether ATRAC's impairment is subjectively more benign than analog cassette's hiss, speed fluctuations, soft bass, and HF rolloff. Despite my reservations about data compression, MD doesn't suffer from the analog cassette's myriad-and annoying-faults.

MD MEDIA

No format can hope to succeed without sup port from prerecorded software and blank media. Perhaps not coincidentally, Sony is very strong in both areas: it owns one of the world's largest music catalogs (formerly CBS Records) and has extensive experience in developing and manufacturing magnetic media. Moreover, they are heavily involved in making magneto-optical computer disks, the technology on which recordable MD is based? To demonstrate their ability to support MD with software and blank discs, Sony took us on a tour of their MD media development center in Sendai, a city of one mil lion about two hours north of Tokyo. Every where you look in Sendai are huge Sony factories producing magnetic media. After a presentation on MD manufacturing, we donned clean-room suits and went inside the factory to see MD disc production firsthand.

We were the first people outside Sony to wit ness MD manufacturing? Prerecorded MDs are made just like CDs: pits are impressed in an injection-molded polycarbonate substrate with a metallintion layer to reflect the playback laser and a protective coating to prevent oxidation. Indeed, the MD production line looked like a miniature version of a CD replication factory.

MDs, however, require several additional manufacturing procedures not required by CDs. First, a metal clamping device about the size of a dime is inserted into the disc's center hole (the MD player spins the disc by magnetically locking on to the clamping device). The disc is then inserted into the plastic protective caddy along with the sliding media cover, write-protect tab, and cover latch. These last steps drive the cost of MD manufacturing above that of CD replication-at least initially. MD's smaller size may eventually make manufacturing costs comparable to that of CD if done on a very large scale. Virtually all the MD manufacturing equipment and robotics we saw had been made by Sony.

[8. In 1978, Sony sold less than $10 million worth of blank media worldwide Last year, their blank media sales exceeded half a billion dollars.

9. This was particularly interesting for me: I spent three and a half years working in a CD manufacturing plant. ]

The Sendai facility also developed the technology behind recordable MD discs. Blank MDs are polycarbonate substrates coated with very thin layers of magnetic material.

A ring of polycarbonate at the inner radius is left uncoated. This area, called "lead-in," has pits impressed in it just as on a CD. The MD recorder reads the information in this un-erasable area, which includes the optimum laser power for recording and the disc playing time. All blank MD lengths are made identically; the only difference between a 74 minute disc and blanks of shorter playing time is the information encoded in the lead-in area: it tells the player how much recording time is available." An additional area, called the User Table of Contents (UTOC), stores track times and locations. This information is written automatically after the disc has been recorded by the user.

Blank MDs also differ from prerecorded discs in that they are stamped with a pre groove to keep the recording laser/magnetic head on track. This pregroove is "wobbled" rather than holding a continuously curving track, a technique called "ADdress In Pre groove" (ADIP). Address information is encoded in these wobbles, allowing random access search to specific disc areas. Specifically, the ADIP carrier frequency is 22.05kHz with a modulation frequency of 63kHz, resulting in an information rate of 3.15kbs.

These parameters allow access resolution of 13.3ms.

A third type of MD disc, call a "hybrid," has both prerecorded program material and a recordable area. The hybrid MD is ideal for specialized applications such as language study.

Sony's blank MD capacity is reportedly 300,000 discs per month from the Sendai factory, with addition production to be provided by other Sony plants around the world.

Ten other media manufacturers-including TDK and Maxell-have signed licensing agreements to manufacture MD blanks.

[10. This is analogous to a trick of the hand-held multimeter industry. The same electronics are in every meter throughout the product line; the less expensive models merely have some of their features disabled.]

74-minute MD blanks will reportedly carry a US retail price of between $12 and $14. No pricing on prerecorded MDs was announced: that will be up to individual record companies. Sony promises that 500 MD titles will be available for the launch, with an annual production capacity of 1.5 million discs worldwide by November of this year.

Sony's Digital Audio Disc Corporation in Terre Haute, Indiana has built an MD line across the street from its CD manufacturing plant.

MDs will be packaged differently in Japan and the rest of the world. US retailers demanded a package similar in size to that of the analog cassette so they don't have to change their display racks. The MD's rectangular outer box is far larger than that required for the tiny MD, suggesting that the box will likely remain at home while the MD is trans ported and used.

MD MASTERING

Mastering studios already making CD master tapes can easily adapt the process for MD premastering; all that's needed is Sony's MD format converter. Here's how it works: A finished 3 / 4 " CD master tape is read into Sony's MD format converter via a standard Sony PCM-1630. The format converter performs the ATRAC encoding and stores the compressed data on an internal hard disk drive.

A blank 3 / 4" tape is put back in the U-Matic machine and the MD-formatted data are recorded on the 3 / 4" tape. Subcode information (track and time information, disc and track titles, etc.) is recorded along with the digital audio signal on the 3 / 4" tape's video track. The MD's much higher subcode capacity (compared with CD) requires this technique.

A key element of the format converter is the ability to ATRAC-encode and -decode the signal in real time. This permits the mastering engineer to tailor the signal processing (eq, for example) specifically for the ATRAC-compressed MD medium.

The MD pressing plant cuts an MD master just as it would a CD master. The only difference is the addition of the MD address generator in the signal path. Because the data are compressed at a 5:1 ratio, a 60-minute MD can be mastered in 12 minutes. Unfortunately, this feature precludes auditioning the tape as it is mastered. The master tape's error rate, however, can be monitored.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Launching a new audio format is a formidable task: not only does it take lots of money (perhaps as much as a billion dollars), but requires support from many areas. It's one thing to develop a new format, but quite another to provide the mastering equipment, manufacturing equipment, blank media, prerecorded product, distribution, and marketing required for the format to even have a chance of survival. Subtract any one of these elements and the whole thing collapses. Sony is uniquely positioned to provide the sup porting infrastructure necessary to give MD a fighting chance.

As a replacement for the analog cassette, MD appears to be a significant step forward--technically speaking. In relation to DCC, I find MD the more attractive technology.

MD is much smaller, more convenient, and has the huge advantages of an optical format--random access, no wear, and neat features like shock-resistant memory. It remains to be seen, however, if there are substantial sound-quality differences between DCC's PASC encoding and MD's ATRAC. Finally, does the public want MiniDisc? Will the analog cassette-listening masses pay MD's higher entry fee for prerecorded music, hardware, and blank discs, or be content with the familiar and inexpensive analog cassette?

UK: Ken K.

What the press calls the silly season-the summer-to-autumn cusp-is so-named be cause there seems to be so little of worth to fill the columns. Which is bull, since the Serbs and Croats, Fergie and Di, Somalia and South Africa haven't exactly been dull topics.

Anyway, this annual malaise also hits the hi-fi scene. In the case of Great Britain, the end of summer/early autumn is the eve before the serious hi-fi selling season begins, while any spare energies are devoted to hi-fi shows.

Chicago, Frankfurt, and Hong Kong have come and gone; London, Milan, and Buda pest are on line. And I'm writing this mere hours before departing for the Penta Hotel at Heathrow-report next month-so I look at this period as the calm before the storm.

But calm it isn't, the recession having spread a pall of doom and gloom over the industry. How do I know? Because I only heard one joke at the Hong Kong Show (report also next month) from a guy usually good for 20 or 30. In other ways, though, the recession has already started to cull the weak and the unnecessary. The dust has settled on the Kinergetics/KEF/Celestion link-up, too, so things aren't quite as chaotic as they could be.

The ray(s) of hope for the UK comes from the most unlikely of sources: a down-market software format and the revival of a moribund one which has great support in the US and the Far East. The former is DCC, about to be launched with fanfare on a par with that of CD in '83, while the latter is laserdisc (or LaserVision, or video disc, or whatever they want to call it). And while DCC is exciting because it's brand-new, laserdisc is exciting because it's wonderful. Which might lead you to ask why it's been denied any success in the video-mad UK. First, let's dispense with DCC, which Philips will be launching with an abundance of razzmatazz at Heathrow. I expect the tabloid newspaper coverage any day now. Initial reactions from colleagues in the trade? "Better than analog cassette, not as good as CD." "Give me a conventional Nakamichi any day:' "Who needs it?" "Terrific for the Great Unwashed." Make of it what you will.

Laserdisc, on the other hand, has those aware of its rebirth shouting "Gimme, gimme, gimme!" Sony, Philips, and Pioneer are about to be inundated with orders from within the trade-reviewers, manufacturers, retailers-keen to get their hands on the first dual-standard (NTSC and PAL) machines.

On the back of it, we'll also see a boom in the sales of dual-standard TV sets, which command, typically, £100 ($200) more than a normal PAL equivalent.

The delay was all caused by the software manufacturers, who ensure CDs sell for £13 ($25) in the UK when they should cost no more than £8 or even £7. What they did was put a stop to consumers sourcing or using the NTSC discs widely available in the US and Japan by forcing the hardware manufacturers to market PAL-only machines in the UK [11], thus forcing consumers to buy PAL discs-which cost a fortune because they're

[ 11. As well as a different, more stable color protocol, the UK's PAL TV system features greater line resolution than NTSC 625 vs 525 horizontal lines-but a slower, more flicker-prone frame rate-50Ha vs 60Hz-te give an identical bancfadddi requirement.

--------

pressed in smaller numbers. This wouldn't have been quite so bad if the film companies had supported the hardware with PAL discs.

They didn't; it was all but impossible to feed a PAL player with a flow of decent discs. But then, albeit quietly, Pioneer introduced a dual-standard machine at a sensible price; it sold like hotcakes. And anyone traveling regularly to the Far East or the US could pick up NTSC discs to feed the machine back home, while others merely ordered discs directly from the US. But what happened to cause this above ground rebellion? What gave Philips and Sony the balls to join Pioneer? It's no longer a secret: there will be a vast array of sub-£600 NTSC/PAL machines in the shops by Christ mas, along with some serious videophile offerings as well.

I can only imagine that part of the resistance to the software manufacturers' black mail is down to the fact that most of the great film companies are now owned by the Japanese, but that's too simplistic. More than likely, the hardware manufacturers realize that the film companies can't do a thing about it. If Sony, Philips, et al want to market dual standard machines, there's no law to stop them. And I'm already hearing about the opening of a number of specialist laserdisc shops in London, offering NTSC discs at sane prices.

Even more interesting, because it also affects video tape, is the launching of the UK's first videophile label. The brains behind Tartan Video belong to Hamish McAlpine, a hardcore audiophile who wants his viewing pleasure to match that of his listening pleasure. The bottom line is simple: All Tartan films will be offered in letterbox format instead of pan'n'scan, the packaging will be generic and informative, the transfers immaculate. And, in most cases, there will be simultaneous release of tape and disc, in PAL format.

McAlpine already had experience in film distribution, having supported Derek Jar man, the maker of impenetrable, tedious, unwatchable, terminally hip movies which were always guaranteed column inches in the quality papers and spots on Barry Norman's influential film criticism series on BBC TV Conversely, McAlpine also knew that he had to distribute films which would sell to an audience greater than the membership of the Groucho Club, so he released and had a hit on his hands with Return of the Living Dead.

That was Tartan's kickoff reissue; 60 others are already scheduled during the next few months, among them modern classics like McCabe and Mrs. Miller, THX1138, and Hearts of Darkness, a critically acclaimed film about the making of Apocalypse Now.

To add more credence to the suggestion that there is a home-viewing revolution underway, Celestion just released the first UK offering in the surround-sound arena, one which undercuts the Japanese by a large amount of cash. The Celestion input consists of two complete packages-Dolby de coders, rear-channel speakers, wire, speaker brackets-which will convert any home hi fi-plus-VCR-or-laser-player to full Dolby Surround status. The HT One offers Dolby Surround for £299, while HT Three adds remote control, Dolby Pro Logic, and a center-channel speaker for £499. So high price is no longer a reason for listening to mono or front-only stereo when watching tapes or discs. (Mind you, some educating will be required. UK video consumers are notoriously stupid, most owners of stereo VCRs lacking the imagination to feed a pair of interconnects into their hi-fis.) To top it all, a new magazine, tentatively called Video Choice, is about to be launched by Hi-Fi Choice. VC will publicize all of the above-laserdiscs, videophile tapes, surround-sound-as well as large-screen and projection TV and all the rest. The editorial balance will probably be 70% hardware and 30% software, but the main difference be tween VC and existing video mags is the tar get audience. Pick up the current offerings and you get either reams of copy about video cameras, dense technical verbiage about set ting up a satellite dish, or in-depth features on Chuck Norris. Video Choice is aimed at the "aspirations" market, closer to US magazine Audio/Video Interiors than Slice'n'Dice Monthly or What Home Movie. And, as a number of the contributors have been borrowed from the hi-fi community (inc. yrs trly), sound quality won't be ignored. Hell, I even bought new spectacles for the project, with a new large-screen, high-def TV certain to cause my credit cards to scream in pain.

So what does all of the above have to do with the current malaise? For one thing, it should mean a sales boom for manufacturers of speakers suitable for surround-sound applications. It will mean TV upgrades. It might even mean-cross fingers-new, better, or second hi-fi systems to accommodate the superior video hardware. Other spinoffs might include a boost for the film-rental shops, now that more members of the public will have access to the extra channels of sound which seem to be available on every new film-even Jean Claude Van Damme's. Cable manufacturers with brains will be able to sell video cables in the UK in greater numbers than a couple of sets a month nationwide.

The hi-fi and video furniture manufacturers will also benefit.

Ordinarily, I keep audio and video separate in my mind/career, even though I use surround-sound at home and have for years.

That's because, unlike the US and other markets, too many British audiophiles are narrow-minded Luddites who scream blue murder if you so much as mention a video product in the pages of a hi-fi magazine. This isn't purism. It's masochism, self-abnegation, and downright stupidity. The challenge for the hi-fi sector (press and retail) will be to integrate the two in a way acceptable to the hi-fi community, which is usually where high-tech home entertainment trends start--even those which need immediate success in the non-hobbyist mass market.

The manufacturers don't have this problem; they simply sell their wares to the appropriate shops. But the shops will have to adapt to the needs of demonstrating home theater, while the magazines will have to accommodate reviews of upscale video and laserdisc machines, as well as the peripherals, the processors, and the monitors. On the other hand, the latter might be better off doing what hi-Fi Choice did by launching separate magazines.

I look forward to the video revolution reaching the UK. It will give me an excuse for not listening to Happy Mondays, rap, Sinead O'Connor, most heavy metal, KLF, and the other dissonant garbage which drove away what should have become the next generation of audiophiles. With music which sounds so awful and is performed so badly, why buy anything more revealing than a ghetto blaster?

[adapted from Nov-1992 issue]

Also see:

No Looking Back -- Roy Goodman (Nov. 1992)

Prev. | Next |