by Adrian Hope

A visit to Teldec, examining prospects for the D-to-D phenomenon.

Is it more than coincidence that despite being produced in North America, virtually all direct cut discs are pressed at the same plant in West Germany?

Adrian Hope recently visited the Teldec disc pressing plant at Nortorf and here discusses the background to the technical problems of direct-to-disc recording and the economic necessity of using a plant capable of producing high quality pressings while obtaining maximum usage of mothers and stampers which, for direct cut, are obviously irreplaceable.

Although HARD FIGURES are impossible to collate, reliable estimates put the number of direct cut discs currently on the world market at around 100 titles, originating from around 60 companies. The figures speak for themselves-only a few companies issue more than one or two direct-to-disc recordings.

Of these few companies, Sheffield and Crystal Clear in the USA and Umbrella in Canada could reasonably be regarded as brand leaders of the western world. The situation is continually changing and I mean no offence to East Wind (which is a Japanese company) or all those other companies such as the Great American Gramophone Company who are doing fine work in the west but on a somewhat smaller scale. Umbrella, Sheffield and Crystal Clear (along with GAGC) have two things in common-their discs are currently pressed by Teldec in West Germany and they are distributed in Europe by Quadramail of London NW3. What more fitting enterprises for Quadramail than to gather 40-50 European journalists in Hamburg for a seminar on direct-to-disc recording and a guided tour of the Teldec pressing plant at Nortorf in West Germany? Apart from making a pleasant break (other firms could learn a lot from the relatively loose schedule arranged by Quadramail- which didn't leave all concerned in a total state of shatter) the event was doubly interesting to me. First, it provided material for my report in Studio Sound magazine on the current boom in direct cut recordings. Second: a year or so ago I visited the Decca pressing plant in South London, which is closely related to the Teldec (Telefunken-Decca) German operation. And to the best of my knowledge no major company has regularly entrusted Decca in England with the pressing of direct cuts.

Although many people, including myself, believe the current fad for direct cut discs will die a natural death in a year or so's time when PCM studio equipment eliminates analogue tape from the recording chain, there is still a massive market for direct cuts.

Witness the number of titles available, the extent to which direct cuts have become virtually a standard tool for audio demonstrations and the price which Joe Public will pay for a direct-to disc recording. In Denmark, an ordinary disc recording costs around $12 and a direct cut around $36-and they still sell like hot cakes.

Quadramail had brought over to Hamburg Jack Richardson and Peter Clayton, the president and vice-president of Umbrella Records. Although neither claims to be an engineer, and both were clearly out of their depth on some of the technical points raised by the assembled press (for instance the maximum velocities cut on Umbrella discs, the stylus cutting angle and the current state of play on PCM encoding) more than enough hard facts emerged to make the trip well worthwhile.

The Umbrella operation pays continual respect to the pioneering work of Sheffield's Doug Sax and Lincoln Mayorga.

The story goes that in 1959 Sax discovered how some 78's recorded in the thirties sounded better than others made in the forties and how in general 78rpm piano records could sound better than LP equivalents. He found that in 1939 the US recording industry moved over from direct cutting of 78rpm masters to recording onto 40.6cm 33.3 (standard groove) masters for subsequent transfer to 78rpm-this was the first step in the chain of degradation.

Then when the LP came in, analogue tape became established as part of the recording chain and that was the second downhill step. Using a 1935 microphone, a 1929 lathe and a 1947 RCA cutterhead, Sax and Mayorga first recorded a piano. It was the sound of the lacquers direct-cut on that ancient system that led to the Mastering Lab, which with direct-to-disc facilities opened in January 1968. Later in that year Sax produced the first modern direct-to-disc Lincoln Mayorga and Distinguished Colleagues. By the way, if you happen to have a copy of this now extinct recording in mint condition you will have no difficulty in selling it for at least $500.

Clayton Richardson and Umbrella are engaged in direct cut activities for only part of the time, routine studio work helping to finance the massive investment needed for a respectable direct cut operation. It is cheap and easy to produce a direct-to-disc recording, provided that you are not unduly fussy over musical and technical quality. This becomes abundantly clear when you listen to some of those hundred direct cut titles currently available. If the musicians can keep going without breaks or mistakes for the requisite sixteen minutes (less for a 45rpm cut) and not overshoot their time to necessitate a fade-out, direct cutting can be a very quick way of producing masters. Studio time is kept to a minimum and there's none of that tedious mixing down to be paid for. Provided the cutting engineer uses compressors and limiters in the chain to the lathe, he can manage quite well even though there is no automatic groove spacing control to keep the grooves safely apart-but not so wide as to drastically reduce program length. Unfortunately, recordings made in a hurry with limiters sound terrible, whether cut direct or not.

Fig. 1: One of Teldec's new automated presses.

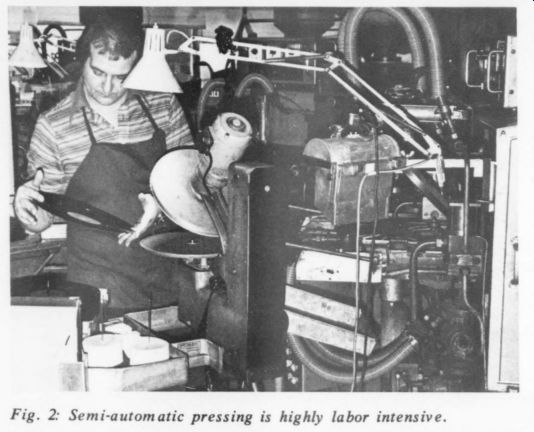

Fig. 2: Semi-automatic pressing is highly labor intensive.

Umbrella doesn't work that way. In fact they recently won the Canadian Juno Award for their Boss Brass Big Band Jazz Album, the first time that a direct cut has won such an award and they are proud that the album won purely on musical content.

The cleanest direct cut sound in the world will do nothing to improve a poor musical performance. The Boss Brass are all top musicians, and Umbrella rehearsed the band for three hours on each side of the proposed album and then cut for real.

The rehearsal is intended for both musicians and engineers who make some test cuts during the run-through. Program length is set at around 16 minutes, or 16 1/4 minutes maximum, per side with the cutting engineer and producer working from a musical score to anticipate each musical climax in the manner of a human vari-pitch control. On Boss Brass there weren't any performance errors but there were technical problems. The fuse in the cutter head blew three times, thanks to the unlimited peaks-three takes were lost but at least the studio saved around $4,000 for a new cutter head each time.

The problems encountered by Umbrella on the Boss Brass album are small compared to those that hit Doug Sax on his recent direct cut symphony orchestra sessions. The whole venture reputedly cost $250,000 and one whole day's work, to the value of between $60,000 to $80,000, went down the drain in a chemical bath.

Anyone seriously into direct cutting knows that the lacquer must be electroplated within an hour or so of cutting to avoid loss of high frequencies due to the lacquer plastic ''losing'' some of the high frequency modulation by relaxing in shape. Sax had installed three cutting lathes for the symphony sessions but to ensure rapid handing, the masters from all three lathes went into the same electro-plating bath. So one mistake ruined them all.

Umbrella have twice lost irreplaceable masters during electro plating. When this happens there is nothing for it but to bring everyone back into the studio for another full batch of sessions and start all over again.

Umbrella have also had problems with cutting styli. Normally they use sapphire of US origin that cost around $30 and last for between 15 and 20 hours. Through Audio-Technica, they secured a diamond stylus of Japanese origin for around $200.

This lasted for 150 hours before it degraded even to the point of sounding as good as a sapphire. But the second and third replacements were unusable and the next they heard was that the company had decided not to make any more. Does anyone know a reliable source of diamonds? An interesting incidental point was raised by Jack Richardson during the Hamburg seminar. In seeking to prove how the use of analogue tape in the recordings chain degrades performance in more ways than the obvious (like distortion and transient compression), Richardson played dubs from a multitrack tape that had passed, first five, and then 25 times over the playback heads during a multitrack session. Even under the decidedly un ideal demonstration conditions in Hamburg there was an audible difference between the bass drum ''edge'' and cymbal sound on the tape after five and 25 passes. Richardson says Umbrella noticed this degradation or erosion only a few times when some out-takes (which had passed only a few times through the studio recorder) were spliced in with some sections of tape that had been much more extensively used.

Note well that we are talking here mot about recorded generations but about the purely physical effect of running a tape a few dozen times backwards and forwards past the machine heads to replay some tracks while recording others. The signs are that there will be HF fall-off after a few dozen passes. But for most pop recording sessions the multitrack tape is run hundreds rather than dozens of times past the heads and so if Richardson's five and 25-pass demonstrations show a difference, what must happen to the average studio tape used for a pop session? Engineers with un-played out-takes of a session available might like to compare them with the finished master for mix down.

Umbrella, and doubtless the other direct cut companies using the Teldec pressing plant, do so for two very good reasons. Firstly Teldec pressings have an enviable reputation amongst the buying public as clean, flat and blemish-free. The factory, to quote Richardson does not suffer from that modern industrial disease "dilution in pride in craft." The other thing going for Teldec is that company's quite legendary ability to get more good mothers, stampers and pressings from a metal master than any other record plant in the Western world.

There is currently a great deal of controversy and confusion over just how many mothers and stampers can be grown from the metal plated master and how many pressings can reasonably be run off each stamper. Obviously some companies produce more mothers, stampers and pressings than others because the more you produce the bigger the profits. But the bigger the profits, the greater the fluctuations in quality, and the more drastic the overall fall-off towards the end of a pressing run. Teldec say the average situation for their ordinary (i.e. not direct cut) plating and pressing is four mothers from the metal plated master, between 30 and 40 stampers per mother and 3,000 discs pressed from each stamper. This makes a total per master of nearly half a million pressings. And of course if the master is cut from tape, there is no problem over recutting for any number of further and similar runs.

For direct cut pressings there is of course no chance of producing a second metal master because the original lacquer is destroyed by plating, but Teldec reckon to get four mothers and 15, or at the most 20, stampers per mother. The number of pressing per stamper is also less, perhaps down to around a thousand. It seems, to firms like Umbrella, that other companies succeed in growing fewer good mothers and pulling fewer good stampers from each mother. They are thus faced with the choice of either limiting the production run or pressing from sub standard i.e. over-used stampers. Either way the firm commissioning the pressing loses out-they get less return on the original recording session or more complaints from the public over poor pressings.

Teldec's summing up of the situation is that "anyone can press a good record with the right machinery, but the final product will only be as good as the mother and stampers." | beg to differ. Anyone should be able to press with the right machinery, but all too few care-Umbrella for in stance found out to their cost how some companies work. One North American pressing plant got through 10 sets of stampers while producing a total of 1,400 pressings, or little more than they should have got from a single stamper. It turned out that the hydraulics of the press were faulty and ten stampers were destroyed before anyone noticed. Because the stampers came from a direct cut session there weren't any more and the whole recording session became a commercial write-off.

The Teldec plant at Nortorf produces around 60,000 singles a day, 35,000 duplicated musicassettes and 100,000 LP's, of which of course only a relative few are direct cuts. But the plant's reputation is such that around 50 percent of that output is custom work sub contracted by other firms. One reason why Teldec has achieved its enviable reputation is quality control. Another is the use (for LP production) of semi automatic presses with a relatively long (32 seconds) operational cycle. It is with fully automatic, short cycle presses that problems such as warp can start to arise.

In fact Teldec is currently moving over from semi-auto pressing to fully automatic production.

Swedish Toolex-Alpha presses are currently being installed. These are programmed for a 26 second cycle although they could be run much faster.

The Toolex presses work on the injection moulding principle and one operator can control four machines. The semi-auto machines are hand served. During our visit there was an interesting comparison to be made between semi-auto and fully auto preses in the Teldec plant operating virtually side by side on the shop floor.

Whereas pressings from the semi-auto machines were being visually inspected with great care by the machine operators, the auto machines were churning out spindled piles of finished pressing with no visual inspection prior to a quality control department to which the pressing are automatically conveyed. This quality control department is clearly diligent but the changeover from semi-auto to fully auto pressing does pose a vital question for those companies entrusting Teldec with their direct cut pressing work.

Fig. 3: Fully automated pressing.

It was clear from what we saw that if one of the auto presses goes hay-wire and starts churning out dud pressings these the quality control department. By this time a mass of dud pressings may have accumulated and a set of stampers been worn out in the process. This won't matter for an ordinary disc release where there is always another set of stampers available. But what if that set of stampers is the last from a classic direct cut session such as the now extinct early Mayorga recording? Hopefully Teldec will decide to retain at least a few semi-auto machines for direct cut pressing, but if not they will need to guarantee direct cut firms special on-the-spot quality control for the auto presses.

The word regrind or recycle is often regarded by record producers and record buyers alike as synonymous with poor quality. It is certainly a fact that if the plant simply regrinds all its reject pressings complete with the paper labels, then the regrind or recycled vinyl mix will be of a poor quality. If dirt from the atmosphere or factory floor also gets into the regrind, then the overall quality of pressing falls even further. But provided that the center label portion of each record is accurately stamped out of each reject pressing before it is reground, it is an open question whether recycling vinyl is detrimental.

Teldec in Germany clearly believe recycling reject pressings does degrade quality because they use only virgin vinyl mix for pressing LPs. On the other hand Decca in England believe just the op posite, arguing that the more times you regrind vinyl the more homogeneous the mix and the better the pressing. Possibly the difference in approach stems from differences between the raw vinyl and chemical mix used by Decca in Germany and in England.

As mentioned above, I visited the UK Decca plant at New Malden a year or so ago. At that time Decca was relying entirely on semi-auto pressing with a 4C second cycle and very rigid quality control at the point of pressing. ''Do away with the press man and you do away with your most essential quality control point,' said the British plant manager. That is exactly what Teldec in Germany is now on the point of doing. So I checked when writing this article with Decca UK on the current situation at New Malden. The presses there are still all semi-auto and there are no firm plans yet to move into full automation. This will make Decca UK one of the few plants in the world still pressing in what big business would write off as primitive fashion. But primitive pressing coupled with pride in craft, is just what the direct cut companies are always looking for ...

-----------------

YOUR MOUTH AND OUR WORD

THE BEST ADVERTISING is word of mouth. Many of you heard about TAA through friends. It is amore believable way to decide to invest $12 in a hobby.

We have a lot of letters from new readers telling us how grateful they are to the people who first told them about The Audio Amateur. If you want more grateful friends-why not mention us. One can't have too many friends-particularly appreciative ones. We also have some prospectuses that tell folks all about us. With these around to hand out you won't have to say all that much. Our circulation DEPARTMENT will be glad to send you a handful.

-----

Also see:

Direct Metal Mastering-- A New Art In LP Records (April 1987)

Soldering: The Basics, by Marc Colen--A thorough, enlightening primer on a vital topic