TAPE RECORDERS

How do you get sound out of rust and plastic? That, essentially, is what audio tape is. That ribbon of thin plastic, generally one-quarter-inch wide, is covered with rust. Rust is, as you know, oxidized iron, and the particles of iron, even though they are oxidized, can still be moved by a magnet. That's the secret. Each particle of iron oxide can point in a particular direction-up-and-down or back-and-forth or in any position in between. When you get a whole bunch of these particles together, as on a piece of audio tape, a magnet can cause them to move around in all sorts of patterns. If that magnet is an electromagnet, it can be made magnetic or nonmagnetic by turning its current on or off. So by varying the electricity going to the electromagnet, you can vary the patterns made in the iron oxide particles. Now, if you can convert sound into varying amounts of electricity, you can use an electromagnet to create patterns in iron oxide. Those patterns exactly represent the varying amounts of electricity from the sound but in a permanent record on the tape. Now reverse the process. Use the patterns in the oxide particles to make the electromagnet give off varying amounts of electricity and convert these varying amounts back into sound and you get back to where you started. A tape recorder is the machine we use to do this process in both directions. It feeds varying amounts of electricity to the electromagnet when it's recording, and it picks up varying amounts of electricity when it's playing back. The con version of sound to electricity, or electricity to sound, is the same process we talked about when we discussed mikes, so I won't rehash that here. However, there's one other thing the tape recorder has to do, and it is so obvious you may tend to overlook it. The tape has to be moved past the electromagnet.

Obviously you can't have everything happening at one spot on the tape or you wouldn't hear anything useful. So you have a tape transport of some sort, which is a way to transport the tape in a continuous run past the electromagnet. For a tape deck, the tape runs from one reel to another. For a cartridge machine, the tape runs from the inside of a spool to the outside.

For a cassette, the tape runs from one hub to another-the same idea as for reel tape. In any case, it gets moved past an electromagnet, referred to as the head. Let's talk of the reel-to reel set-up first.

On the left is a reel holding the blank tape. That's called the feed reel. On the right is the take-up reel, and its function is obvious. The tape goes in a shallow curve down between the two reels and thus against a series of heads, and between a roller and a capstan. This roller and capstan squeeze against the tape and, depending on how fast they turn, pull the tape past the heads at 15 inches per second (ips) or 7 1/2 inches per second, or even slower. Generally, broadcast operations use 15 ips, occasionally 7 1/2, almost never 3 3/4, and never 1 7/8. Home recorders, on the other hand, often do not have a 15 ips speed.

Whatever the speed, the roller and capstan pull the tape past the heads. Even if the tape is not on a take-up reel, it gets pulled past the heads and will then just spill out on the floor, but at least it will be pulled past the heads at the proper speed.

Fig. 23 A reel-to-reel audio tape machine

Assume, though, you do have a take-up reel and you are running at 15 ips. The tape, coming from between the capstan and roller, goes around an idler arm before it goes onto the take-up reel. This arm will fall down unless the tape holds it up. So as long as tape is going from the feed to the take-up reel, the idler arm can be held up. What happens when it does fall? The machine shuts off. So when you get to the end of the tape, even if you do nothing yourself, the machine stops.

If the tape should break while it's playing, that too lets the idler arm down and the machine stops. If that happens on the air, you may have to keep the tape playing regardless. Hold the idler arm up with your finger, and the machine starts playing instantly. You will also instantly be back on the air, but the tape will be piling up on the floor. Let it. You can take care of it later, but do it gently; don't fold it or crease it or mash it. Also, clean it.

Now, what about the heads? Generally, there are three.

Think about what you want done with the tape. First you want to make sure nothing else is on the tape, so you won't be re cording over other sounds. So the first head is an erase head, and its only function is to remove all sounds from the tape by putting all the oxide particles back in one pattern (all up-and down or all back-and-forth, etc). Next, you want to put some sound on the tape. So the next head is the record head, and all it does is feed in the varying amounts of electricity and hence the varying amounts of magnetism. Third, you want to hear what you've recorded, so the third head does nothing other than play back the material now on the tape. The three heads are always in this order-erase, record, playback, or ERP. Some times, a tape deck will combine the record and playback functions in one head. That's especially true on home machines but is very seldom true on broadcast machines. With separate record and playback heads, you can listen to the recording almost at the same time it's being made. Quite often a broadcast tape deck has a circuit connected to a headset and gives the playback head only. That way, you can put a record on the turntable, start recording it on the tape deck, and listen on the headset for any problems you might not have anticipated.

It's an instant check on the quality of the recording. But be cause the record and playback heads are separated by a bit of space, the sound from the disc and the sound from the tape will not be precisely together. The disc, of course, will come first, as that's what is going into the record head. Then it passes to the playback head, and so a split second later, you hear it over the headset. Suppose you have two tape decks.

You set up both to record, but one you set up to record from the turntable and the other you set up to record from the output of the board. Now feed the playback of the first tape deck back into the board. What you'll now have going in to the second tape deck is the turntable, and a split second later, the same sound from the playback of the first tape deck. So you get an echo effect. Another gimmick on some tape decks is a switch to kill the effect of the erase head. That allows you to record over something already on the tape, so you get what's called sound-on-sound.

Just how do you go about making a recording, even a simple one? It's easy. The tape deck has a VU meter. As your sound source plays a record, for example, set the tape deck VU meter and the board VU meter so they read the same. You do this by adjusting the slider on the board for the sound source and the pot or slider on the tape deck for the VU meter. Then check to see you have turned the speed indicator to the one you want.

Somewhere you may also find a switch which says "record- playback." Put it, of course, on "record." If you find no such switch, you will undoubtedly find a button which says "record." But if you push it, it won't stay down. Even if you had a switch which you turned to "record," you wouldn't be ready to record.

You will have to do two things at once to get the tape deck going. This is a safety measure so you don't accidentally go into record when you don't mean to. Once you start to record, the erase head will take off whatever else is on the tape, and you don't want accidentally to erase the only copy of something important. So if you have a switch turned to "record," you will still have a button somewhere to hold down as you turn another switch to "play," or punch a button marked "play." The tape deck will start going, and it will be recording. Also, somewhere on it a red light will come on to show it is indeed recording.

With all these warnings, it's hard to accidentally erase a tape, but you may do it someday anyway. What can I say except you'll hate yourself? Obviously, the easy thing is to start the tape deck recording, then turn on the turntable. You'll get a little silence at the head of the tape, but you can take care of that later. Just re member, when you are recording, have the key to the tape deck turned off. Otherwise, the signal will be taken off the deck, fed to the board, which feeds it back to the deck, which feeds it back to the board, and so on. We're back to the feedback cycle.

That will ruin your recording.

But what of playback? That's easier yet. If the deck has that "record-playback" switch, put it in playback. Open the key for the deck, push the slider up, and punch the deck's play button or turn the deck's start switch. Watch the VU meter on the board, and you have whatever is recorded on the tape. To cue up to the first of the sound, go either to the cue or audition positions on the tape deck's switches on the board. Then start the tape rolling. As soon as you hear the first sound, hit the stop button. Now with one hand on each reel, rotate them back and forth. You can hear a low growl of sound as opposed to the silence. Set the tape at the first note of the growl, or just a hair before if your machine takes any time to get up to speed.

Now set the key in "program" and the slider at the right level, and you are cued and ready to go.

One other detail. The feed and take-up reels should be the same size. Big, medium, and small reels all have different sized hubs, so the tensions can change on the tape as it goes from a small hub to a large one. If you are in fast forward or reverse and stop the tape, the changing tensions can stretch or even break the tape. So always use the same size. Also, be sure to put stops of some sort on the reels. Stops are the rubber or metal clamps that slip over the center spindle of the deck to hold the reel on. They keep the reels from wobbling up and down (or in and out) when you use fast forward or reverse. And that, obviously, helps to prevent the tape from being damaged. Tape decks, which can be mounted either horizontally or vertically, are better off with stops.

Fig. 24 An audio cartridge record-playback machine

A second sort of tape player is the cartridge machine, or cart machine for short. These tape players very seldom have an erase head, so you have to bring a clean cart to them. Every broadcast operation will have a large electromagnet some where which you can use to bulk tape. That simply means to erase all at once, or in bulk, all the material on the tape, in stead of a piece at a time the way an erase head does. You turn it on, the electricity creates a strong magnetic field, you bring the tape to it, you take the tape away, and you turn it off.

Now all the particles are aligned the same way. Be sure you take the tape away before you turn it off, because when the electricity is turned off, the magnetic field collapses and shifts in differing directions. So the tape picks up low-level, random noise which will sound like a hissing noise on the tape. Other things cause hiss too, but this is one source of a small bit of it.

Also, beware of having other things sitting near the bulker that you don't want erased or magnetized, such as other tapes, watches, etc. This erasing process is also called degaussing, in honor of Karl Friedrich Gauss, who worked a lot with magnetism. So, now that you know how to bulk or degauss a cart, let's get back to the cart machine.

The cart machine is a simple device, having generally only an off-on switch, a stop button, a start button, and a record button. Somewhere also will be a VU meter and a slider to adjust it. To record with the cart machine, put the cart in.

Slide it in flat and up against the right-hand edge of the opening. Don't slam it in because the heads are at the end of the slot, and if carts keep getting slammed into them, they slip backward a bit and eventually can't maintain contact with the tape. Then you get no sound. So slide it in easy. Flip the off-on switch to "on." Start your sound source and set the board and cart machine vu meters to the same level. Then cue up your sound source. Push the cart machine record and start buttons together and start the sound source at the same time. You're now recording. At the end of the sound, push the stop button.

Then push the start button only. This makes the cart play around to the beginning again, but it doesn't record anything.

As with the tape deck, you must be sure the cart machine key on the board is off while you are recording, or you'll get feed back.

To hear what you've recorded, open the key on the board, push the slider up, and push the machine's start button. What- ever you recorded will play back, and at the end, the cart will keep on running until it comes back to the beginning. When ever you start recording on a cart, the machine will automatically put an inaudible tone on the tape which tells the machine where the start is. Sometimes, if you start the cart and music exactly together, a bit of music gets on before the start cue. Then, when the cart recycles, you will hear a note or two of music before the cart stops. To avoid this, start the cart and then start the music. The difference can quite literally be less than a second, but you will avoid that extra beep of sound as the cart recues. Generally, you never push the stop button after a cart has started to play; you let it go around till it recues, so the cart is always ready to go. But if it's the wrong cart, or if you need the machine for another cart right away, don't hesitate to stop a cart and remove it. Just be very sure you later put the cart back in and start it so it can get around to the beginning again.

Fig. 25 An audio cartridge. The tape comes off the hub at the center,

runs left to right across the front, and returns to the outside of the reel.

Carts seem to lock into the slot once they are pushed all the way in. That is, you can't pull them straight out. To remove one, put your fingers underneath, lift up, and slide it out. The lifting up releases the catch, and it takes no force at all.

Always label a cart when you record on it. Don't rely on your memory, as all carts look alike. A stick-on label on the end, not on the top or bottom, is common, but every so often stop to peel off the accumulated seventeen or so labels which have been put on top of each other. I say not on the top or bottom because some machines use the top or bottom surfaces to hold the cart in alignment with the heads. If labels are there, everything is thrown off. Besides, a label on the top or bottom can't be read while the cart is in the machine, and sometimes you need to so you can figure out what happens next.

The final form of tape machine you will encounter is the cassette player-recorder. Like the cart machine, it accommodates a box containing the audio tape. The difference is that the tape runs in one direction and stops. It doesn't recue. You have to turn the cassette over to get more sound, and playing through on the second side automatically gets you back to the beginning of sound for side one. There are variations of this form which move the playback heads and automatically cause the tape to start running in the other direction so you don't physically have to turn the cassette over. These variations are most common in the tape machines we see in cars or in some home players. But most broadcasters deal with the sort which requires taking the cassette out. That's because the machine is primarily used by reporters out getting interviews.

A cassette recorder and microphone are about the size of a couple large books and weigh about the same. The recorder is so perfectly portable that interviews and on-the-spot recordings become a snap. Once the recording is done, the cassette can be played back through a cassette playback unit permanently wired into the board, or on a unit put into the board through the patch panel. But more about the patch panel later on.

Cassette recordings are becoming more and more commonly used by stations as the quality of the sound improves. The tape in a cassette machine is only one-eighth inch as compared to the one-quarter inch of other systems, so for a long time everyone assumed the sound quality couldn't be as good. But engineers labored away among their wires and IC's and came up with eight tracks on one-eighth inch that sound fantastic.

Now music recorded on cassettes is comparable in fidelity to music recorded any other way. So more and more broadcasters are using cassettes as a music source for their boards. This, of course, does not invalidate the uses of cassette recordings in news. That's still fast, easy, and of excellent fidelity.

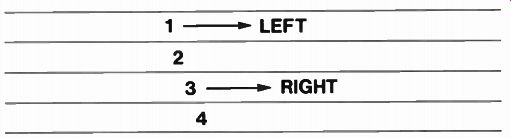

Fig. 26 Audio tape tracks-first direction

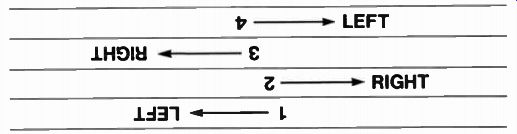

Fig. 27 Audio tape tracks-second direction

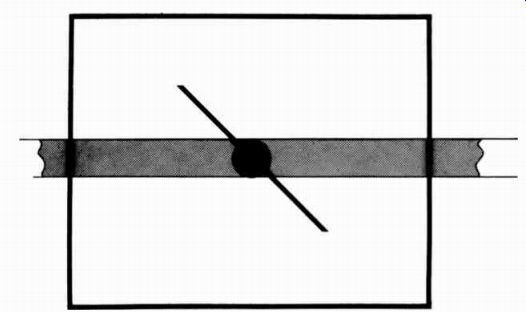

Fig. 28 Editing block tape

What of the tape itself, now that we have talked of the machines it plays on? It's generally only one-quarter inch wide, but it can have a lot of information on it. In most broadcast operations, you encounter full-track or half-track recordings. Here's what that means. For full track, the entire width of the tape, all one-quarter inch of it, is devoted to a single output from the board. That one output may be as complex as a symphony orchestra, but it's still only one output. For stereo, you need two outputs, a left and a right channel. So broadcasters go to half-track recordings. The left channel is put on one-half of the tape and the right channel on the other. Stereo playback still plays the whole tape width, but half goes to one side, half to the other. Most home recorders work with even less width. They are quarter-track machines and work like this.

Imagine the four-quarter tracks as numbered 1, 2, 3, and 4 from the top down. Tracks 1 and 3 will have the left and right in formation on them. At the end of the tape, when you turn it over, track 4 is now highest so tracks 4 and 2 get the left and right information going back the other way. What would happen if you took this tape to a broadcast operation? Those machines would play the whole width and get some music running backwards. So you generally can't record at home and use the recording in a broadcast studio. You can, however, if your tape is clean and you only record in one direction. But your equipment had better be good, or all the flaws will show up.

You can also cut this tape and add in bits of music or take out bits of bad or unwanted sound. You judge where you want to cut by playing the tape, and at the particular sound you want to eliminate, you stop the tape. See where the tape is on the playback head, pick it up and place it on another surface, and mark that spot with a grease pencil. Then thread it up again and go on playing till you get to the end of the part you want to remove. Again, stop the machine, see where the tape is, remove it, and mark it. Now, with a sharp razor blade and a metal block called an edit-all, fit the tape in the groove in the block. It's exactly one-quarter-inch wide. Put the grease mark right over the narrow slanted slit in the block and cut the tape by pulling the razor blade through the slit. Do the same at the first grease mark. Remove the middle piece of tape, bring the two ends together (and they fit because they were cut on the same slant), and tape them together with a special tape called splicing tape. Then use the razor blade to cut off the edge of the splicing tape. Cut slightly wasp-waisted at the spliced point so the sticky stuff of the tape won't rub against parts of the tape deck. Now, when you play the tape, the un-wanted part will be gone. You can get good enough at this to eliminate one sound of one letter of one word if you want.

Tape editing is a real art and can be undetectable if carefully done.

Fig. 29 Spliced audio tape.

Be careful with tape. Don't store it near electrical motors, because they generate electrical fields which can upset the particles. Keep it in boxes so it stays clean. Keep it cool, as heat can make it brittle. Label the boxes so you know what's on the tape. Also, if you don't play a tape very often, rewind it at least once a year. This is because the particles will in fluence those close either above or below them and will move them somewhat. This could produce a faint echo of sound one layer up or down. Rewinding once a year moves everything around enough to destroy such "print-through" patterns. Carts, because of their constant reuse, seldom face this problem.

You'll get a lot of tapes sent in to the station, some with commercials, some with jingles, some with just plain music.

These can come in on carts, cassettes, or reel-to-reel. The reel tape is the most common. Take the case of jingles. Your station management may buy a package of jingles from a company specializing in the creation of ID's, show themes, stingers (the short music bursts used for emphasis) and any number of other specialized music needs. All these jingles arrive on one tape. You'll want to dub these over to separate carts, one for each jingle, so you can identify the particular one you want and play just it without having to search through that whole tape of jingles. The same is true with commercials. You may get a tape with four or five commercials on it. Perhaps each one is to play for a week, followed the next week by the next one on the tape. A dub of each one over to a cart makes each one instantly available to you. Some stations even transfer all the songs they play over to carts just for convenience. Besides, all this dubbing eliminates wear on the original source. Records wear out, tapes played often can get broken or creased. If you are dealing with a dub and something happens, you can always go back to the original and start all over again. Besides, the prerecorded material you get in is at all sorts of different sound levels. One tape may be very loud at a slider setting of 6, another very low. If most of your program sources sound about right at 6, dubbing the prerecorded material over to carts at the right level for you gets everything back near your standard of 6. Of course not everything will be exactly right at 6, but they can come close, and that's handy.

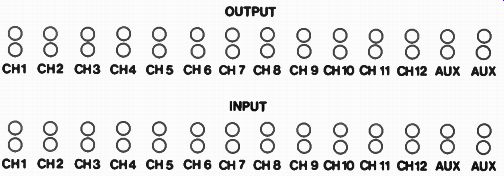

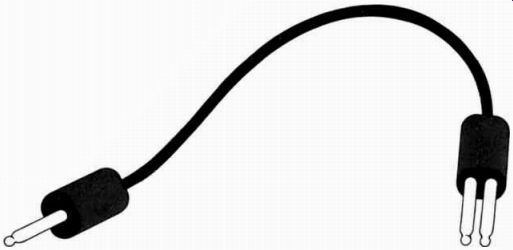

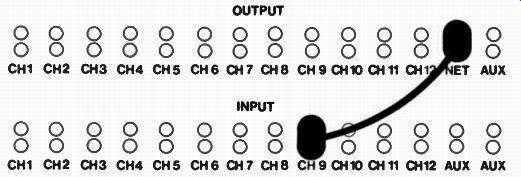

Fig. 30 Patch panel Fig. 31 Patch cord

PATCH PANEL

Now let's get back to the board itself.

Just because the fifth slider from the left is labeled "TT2" doesn't mean it must always control turntable two. Sure it's possible to get inside the board and rewire so that suddenly tape deck one comes through there. That's a long-term change though, and there is a way to make a short-term change. It's called a patch panel.

Somewhere near the board you will find a series of holes.

They come in pairs and there are generally two pairs for every function of the board, plus a couple more. A device called a patch cord will fit in a pair from either end.

Suppose you take a patch cord and put one end in the pair of holes on the top, or output, row for tape deck one and put the other end in the lower, or input, row for turntable one. Now when you flip the switch for turntable one and move the slider up, you will hear the tape deck, plus the turntable. Here's the story. A patch panel has the material from each slider going to it. By plugging into the output section, you can take the sound out of the patch panel. Then, with the other end of the cord, you can put the material into the panel by going into any of the input pairs. So if you have music playing on tape deck one, you can take it out of the patch panel, and hence out of the board, and put it in anywhere you want it. That includes putting it into something other than the board if you want.

Suppose you have two tapes on open reels and you want them mixed to another tape. You can take the output of tape deck one and put it into tape deck two, thus getting both sounds together. But how do you record now, since both tape decks are in use? You take the output of tape deck two, now both sounds, and put it directly into another tape deck which is not connected to the board. Most tape decks have an input jack, and that's what you plug into. Quite often, this input jack is a single, not a pair. That's OK, though, because patch cords come in a single-double form.

Or suppose you have a tape you want to play on the air but all the machines are going to be in use for the production. You can patch in an outside tape recorder by use of a single-double plug going from the output jack of the tape recorder to the input pair of whatever slider you choose.

There are other uses too. Often on a board you will have several things coming through one slider. Generally they are things you don't often need together, like a network feed line and a supplementary studio tie-in. But someday you're bound to need both simultaneously. The patch panel will have a pair for each, so take a cord and put one of the two into another slider. Say slider ten has a five-position selector switch above it, the net is position one and the other studio is position two. Put a patch cord into the other studio pair on the panel and go into the input for slider nine. Set the selector switch on slider ten for one and you can now get the two things separately, as you would any other two separate sources.

Suppose, just before air time, you check one of the mikes in your studio and you get nothing. You check the mike itself and it's fine, but to check it you had to move a mike you knew was working because all your mike outlets are in use. In other words, it looks like the circuit in the board is dead, since the mike works elsewhere. Go ahead and plug it in the nonworking circuit and patch out of it to some other position on the board.

You should, then, get something from the mike. If you don't, the fault is between the plug in the studio and the board, and that can't be fixed before air time, so find a way to fake it through the show. That happens rarely, though, so the patch can become an emergency first-aid measure.

Fig. 32 Double-single patch cord

Fig. 33 Patched channels

You may also want to move some things around so as to get all the sliders for a particular show bunched in a row instead of strung out all down the board. A few patches can line you up in sliders 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, which can be a blessing in a complex show.

The major problem you have to watch for is a difference of levels. Generally when you move the sound from one slider to another, it's because the slider you move to is not being used for anything else. But if you are running two sounds together on one position, remember that you can't adjust their sound levels individually. If you change one, you change both.

So if one source has a high level and the other a low one, you've got problems. In that case, a patch gives you a problem instead of solving one. Figure out another way to do it.

That covers all the pieces of equipment you have to deal with. Now you need to know what you're going to be doing.

Again, scripts become your guide. They are the written form of somebody's ideas on what should come out of that board you can now manipulate. So let's talk about scripts.

RADIO SCRIPTS

The heading on a radio script should give you instant information about whether or not you've picked up the right script.

If you're looking for the script for the sixty-second commercial for Sunshine Soap, you should expect to find a listing of the time and the product on top of the first page. Because the sponsor's name can be different from the product's name, you'll also see the sponsor's name there. Other information may be there as well, like the particular show the script is to be used for (if it is limited to one show), perhaps the date when it was written, and whatever else the writer, agency, or station finds relevant. So the heading might be something like this: Sponsor: Gilding Co.

Product: Sunshine Soap Length: :60 Program: I Dream of Tomorrow Date: 30 February 1977 Below that, centered on the page, is the indication of who is reading. This goes in all capital letters, as does all material not to be read.

ANNCR. Baby your skin with Sunshine . . . But suppose there is to be music under the announcer's voice throughout the spot. That sort of notice goes in the body of the copy, but in all caps.

ANNCR. (MUSIC: ET "SYMPHONY IN GREEN, " SIDE 1, CUT 4.

MUSIC UNDER. ) Baby your skin with Sunshine . ."ET" stands for electrical transcription and refers to what you normally call a record. Any directions other than the name of the reader go in the body of the copy in all caps. If, for example, the announcer is supposed to read (SINCERELY), that's the way it appears in the copy. Sound effects (WIND), sounds from unknown sources (MUFFLED LAUGHTER), and any other such information intended to create a real situation go in the body of the copy in caps. Some people use a system of single under lines for music cues (MUSIC: ET, "SYMPHONY. . .") and double underlines for sound effects (WIND). Such signals do make the various segments stand out more clearly and can be a great help to the harassed board engineer trying to skim through a script to see what s/he has to have ready.

At the end of our Sunshine spot, the announcer finishes and the music stops. You needn't go through naming the piece of music again. Just put (MUSIC OUT). Or if you specifically want the music to slowly disappear, put (FADE MUSIC OUT). At the bottom of the first page, the second page, and so on up to the last page, put (MORE) centered on the page so the reader knows to go on. At the top of the second and third and sub sequent pages, put the title, like "Sunshine Soap" or "Murder in the Night," and the page number. When you do finally come to the end, put some symbols like -0- or ##### or even -30 to show there are no other pages. The -30- is most common in newspaper work, but it shows up in broadcasting too, generally from people who started out on papers.

Don't divide words at the ends of lines. Don't break in the middle of a sentence at the bottom of a page. Even if you end up with a lot of empty space at the end of a line or page, keep the units together. The reason is that people reading are often on "automatic pilot" as far as the words are concerned.

Their thought is on breath control, the emotion they are putting into their voices, on maintaining an accent for their characters, or on some such other point. If a break comes, that may upset both their rhythm and concentration, thus making them sound bad. Since the air sound is your main concern, you don't want that. So keep the script direct and easy and don't break words or sentences.

Besides the script, another essential in knowing what to do and when is the station log.

THE RADIO LOG

The only way a jock or an engineer knows what is supposed to be on the air is by looking at the log. There, all typed up, is a listing of times when programs start or spots run, numbers for which carts have which commercials, indications of whether a spot is a commercial or a public service announcement, and so on. For each day of the week, the traffic department turns out this guide to the day's programming. Certain basic things have to go on this log, so let's take a look.

First, obviously, has to be the title of what's running. This is something like the "Johnny Michaels Show," or "Music from Latvia." Next, and equally important, is the time it starts.

So the log starts out looking something like this: 8:30:00 Music from Latvia Now, we need to know if the show is being done live or if it's all on tape. So somewhere there will be a column which tells you "Live" (sometimes "Studio") or "tape #47." Within the show will be commercials and public service announcements, all of which can come at varying times; these too will be identified as live or tape.

8:30:00 Music from Latvia Tape #47 Winfield Dodge Live A & M Supermarkets Cart #39 Latvian Club Tape #17 If the station runs on a particular format, with certain events always happening at certain times, like a three-minute song followed by eight seconds of the jock talking followed by a minute commercial, it would be possible to list the exact times each of these three spots should run. Otherwise, the time column will be left blank. Speaking of time, how do you know how long each of the spots is? There will be a column headed "Length" to list just exactly that. You'll also want to know which spots are commercials and which are public service announcements; another column will tell you that.

8:30:00 Music from Latvia Tape #47 28:37 Ent.

Winfield Dodge Live :30 CA A & M Supermarkets Cart #39 :60 CA Latvian Club Tape #17 :30 PSA Now comes the problem of telling just when within the show (assuming you're not on the tight three-minute-eight-second- one-minute type format) the breaks will come for these spots.

When the show was originally taped, the people knew they had to break first for :30, then for :60, and so on. By checking the clock, they could record how far into the show the first break came, the second break, and so forth. This listing will be provided to the jock and the engineer on a separate run-down sheet. Sometimes it is included on the log, but most often it's separate. Now what happens at the end of the show? We know it will come out at 8:58:27 because that's the time it started plus the length listed on the log. So we'll have this: Latvian Club Tape #17 :30 PSA 8:58:27 Joan's Boutique Cart #103 :30 CA 8:58:57 Lyric Theater Live :10 CA 8:59:07 Beef & Bird Restaurant Cart #88 :30 CA 8:59:37 Jones Insurance Cart #114 :20 CA 8:59:57 ID Live :03 ID 9:00:00 Johnny Michaels Live 2:58:30 Ent.

Show The "Ent." is one possible abbreviation to indicate an entertainment show; "Var." for variety is another example. But back to the station break.

We can see that once the Latvian show ends, we go to a series of commercials, an ID, and into the next show, which is a live jock doing his three-hour shift. The only other essential for the log is a space to show when items actually did get on and off. Machines and people being what they are, errors will happen and sometimes everything gets on late (rarely early). So somewhere will be two columns labeled "Time On" and "Time Off." 8:59:57 ID Live :03 ID 8:59:58 9:00:04 The jock was just a bit late, and said a bit more than normal going into the next show. No harm is done, of course, and probably the station got a little extra hype for the "Johnny Michaels Show." If something screws up so badly a spot is missed altogether, the jock may run it later in his show, in his next break (if he's not on a tight format); or if it was supposed to be in a station break, the jock may run it within his show at the first break. Some stations do this as a matter of policy, some don't.

Running a spot again to make up for one that was missed is called giving a make-good. Because some sponsors buy very specific times, make-goods aren't given as a matter of policy until they are checked out with traffic. If a sponsor is buying a general time period though (between 8 P.M. and 10 P.M., say), then a make-good given at the next break is perfectly acceptable.

If a station is totally sold up and only runs a certain number of spots per break, make-goods are impossible. There is no room for them. So the missed spot gets reported on a discrepancy report (a daily listing of all the errors of the broadcast day), and the traffic department will, the next day, see the report and reschedule the spot in an appropriate time.

Someone is always designated as the official keeper of the log. This may be the jock on the air, the engineer on the board, or even a transmitter engineer. But for both radio and television, someone has to be responsible for checking off the events as they happen, and recording the time they run. Then, when the shift ends, s/he signs the log. This makes the log an official document which can be used to prove the spots did run and the sponsors can be billed for them, and to prove to the FCC what the station actually does with its air time.

But logs and scripts and equipment are of no use to anyone without a person to put them all to work. Somebody has to come into the control room and put everything together into a smooth, finished show. That someone can be the promotion manager or program director, or even the jock, but whoever it is, let's call that person a radio producer, because s/he actually produces the air product, be it commercial, drama, or news.

THE RADIO PRODUCER

Radio's chief advantage over television is the human mind. As Stan Freberg once said, "Television expands your mind, but only up to 21 inches." If radio wants to move from the Taj Mahal to New York's Empire State Building, some Indian music and the right accent on the announcer can be followed by some taxis beeping and a different accent, and the move is accomplished. In television, you may have a problem as complex as flying the film crew and actors to India for a day or two, and then to New York to finish up. A radio producer, then, by being aware of the differences in sound, can create an entire world in the listener's mind.

That means that when you are sitting at the board, you can create almost any part of human existence if you use the right inputs. If you are doing something as simple as a :30 spot for a local bank, you will want different sound effects than for a :30 for the local supermarket chain. Even if the bank is trying to convey a new, fresh image, they don't want nervous, agitated music in their spots. They are selling a sense of security as well, and nervousness certainly doesn't lead to security.

Suppose you are making a spot for an airline to run during the winter in the northeastern states, and the pitch is to fly south for a vacation on the beach during the nastiness of northern snow time. You might start out with the sound of gentle surf hitting the beach. In the dead of winter, that's a very seductive sound to a northern ear. But if you listen carefully, you realize the surf sound isn't immediately identifiable. So you throw in the call of a seagull, and you have a whole scene building up in the mind's eye. Make use of some soft announcing building to a rising tempo theme and you can tie the thoughts of sand and sun and sea to the thought of an air plane and cause a shivering stampede into the airline's offices.

Admittedly, you sometimes have to say a lot more in a radio situation to set a scene than you do in television. For example, the hero walks into a darkened room and says, "It's too dark in here. Where's the light switch? Wha. . .? (THUD. HURRIED FOOTSTEPS FADING OUT.)" He's been hit on the head by an unknown assailant and knocked out. In television, he wouldn't say anything. We can see it's too dark, and with the proper shots, we can see him get hit. But the result is the same; we still know the hero is down and the villain is getting away.

Dialogue, a sound effects person punching a sandbag, and an actor rapidly walking off mike and toward a corner of the studio give us all the realism we need.

These are examples of the well-chosen sound or piece of music, but one other production advantage of radio is audio tape. Since you can cut it up, you can get the exact sound you want and stop or start at exactly the right spot. If the build of a piece of music has to hit at exactly a certain word in the script, you can record the music and the words on separate tapes, then cut them to exactly the right lengths. Start them together and the two sounds will occur at exactly the instant you want.

Or you can just record the music, time it to find out where the peak comes, then figure out how long it takes to get from word one to the peak word, and just start the tape at the right number of words. If you want to end at a certain time, you can time the music tape at, say, :13 and then start the tape thirteen seconds before you're through and so come out exactly on time. Tape gives you a precision of control over the sound you want, but you still have to be sure you know what you want. Sharpening up that connection between ears and brain becomes a lifelong process for an interested radio producer.