Before we even start to talk about the various people at the station, I want to discuss a subject that lurks in the backs of all their minds-ratings. The amount of profit the station can make, the shows that live or die, the programming decisions that are made, and the people who keep or lose jobs can all depend on the ratings. They arrive in a book filled with numbers, provided by a rating service. They are both eagerly awaited and slightly feared by the majority of people I will discuss later, so in order to see just what it is that has such an impact on the station, its people, and its operation, let's take a look at the rating services.

RATING SERVICES

Ratings are percentages. We've all heard of programs getting ratings of 18 or 22 or 3. Those numbers mean that 18 percent or 22 percent or 3 percent of the total number of people in the broadcast area were tuned in to that particular show. How do the rating companies get those numbers? They randomly pick about a thousand people and ask them to keep a record of what they watch or listen to for a week. Generally they do this with four groups of a thousand each for each of four consecutive weeks. Then they compile the four thousand records, figure out the percentages, and give them out to the stations. Since this is a lot of work, the stations have to buy these figures from the companies. The major companies are Hooper and Pulse for radio and American Research Bureau (ARB) and Nielsen for television. Depending on the size of the area, this is done three times a year for a relatively unpopulated area, five, six, or seven times a year for a metropolitan area, and in the case of really big cities like New York and Los Angeles, it is done almost every week of the year.

There are several ways these companies have people keep records of what they listen to or watch. The most common method is a diary, a simple listing written out by the person showing what programs were watched or listened to, and at what times. Another way is to call people on the phone and ask them what they are watching at the moment. That's called a phone coincidental, because it's coincidental with the time the show is on. Sometimes companies also call and ask what was watched or listened to the day before. That's called a phone recall survey. This same sort of thing can be done by having a person actually go out to homes and interview people, but this interview method isn't used too often because it's so much more expensive than phoning. A fourth method used in some larger cities is to attach a box to a set which automatically records when the set is on and what channel it is tuned to.

Obviously, this only works for television. But whatever method is used, ratings are not the only pieces of information the services provide.

They break the audience into groups like men eighteen to thirty-four, women eighteen to forty-nine, teens, children two to eleven, and so on. They give a percentage figure for each of these groups, so that rating of 22 gets broken into 2 for men eighteen to thirty-four, 7 for women eighteen to thirty-four, and so on. This is referred to as the demographic breakdown be cause demographics refers to the statistical characteristics of portions of the population, in this case, a statistic of how many were listeners or viewers for a particular program. You may think you have a show for men in their twenties, but if several rating books show the audience to be mostly teenagers, you might want to attempt to find an acne cream sponsor instead of the singles-cruise ship line.

There's another statistic provided by the books, and it's often more useful for stations. That's share, a percentage of all the people who are listening to or watching any station at all in the area. You might have a rating of 22, which means that 22 percent of everybody around, and a share of 48. That means that of all the people who has sets turned on, 48 percent were tuned to your station. Suppose the area has a population of 100,000. With a rating of 22, you have 22,000 in your audience.

Suppose that out of that 100,000, only 46,000 were listening to or watching anything, your station or anyone else's. Your 22,000 is 48 percent of that 46,000, so you have a share of 48. Share, then, tells you how you are doing in terms of the competition.

That's very useful. Suppose you have just put on a different sort of late-night show, and the rating book shows a low number of 3. That sounds terrible. But look at the share and you may see something like 65! That means that almost everybody around is asleep and, of course, not listening to or watching anything. But of those 3 percent still up, you are getting 65 percent. Your show is very successful. However, you still can't charge the sponsor much because the total audience size isn't big, but if s/he wants the night owls, you're the station to come to. So the share can tell you if your programming decision is working.

Those are the major pieces of information which rating books will give you. As with any statistical work, there are a lot of other things that get listed, and there are a lot of other uses for the books. One quick example. The sales department will look in the book to see how many thousands of people were in the audience for a particular show. Then they will take the cost of one spot in that show, divide it by the number of thousands, and get a figure called the cost-per-thousand, or CPM. They want low CPMs so they can pitch those spots to sponsors as better buys than the competition (hopefully with higher CPMs) can offer. But this gives you an idea of what the books provide, and you can see why so many people around the station use them. You can guess how a show is doing, but the books will give you far more exact information. That exactness is important for many decisions made by a number of people. Now, let's move on to those people and see just what they do.

STATION PEOPLE--THE GENERAL MANAGER

Every organization has its leader. In a station, it's the general manager. S/he is the big boss, the person everyone answers to.

Now, s/he may have to answer to someone higher up, such as a corporate vice-president or stockholders, but in general s/he is the person everyone at the station looks to as the boss. So the general manager's responsibilities include everything. S/he has to be sure the station makes money, gets good shows on the air, produces local shows smoothly, satisfies local needs, covers the news fairly and completely, adds new members to the audience and keeps the old ones, and generally makes everyone happy to work there. Of course s/he can't do all this alone. S/he delegates responsibilities to department heads and expects them to be experts in their particular areas. S/he has to know enough about each of their jobs to be able to judge their competence, but s/he doesn't have to be able to do each job as well as they can. The general manager's expertise has to be in getting all these people to work well together. If the production manager and the program director are bitter enemies, the shows done locally will suffer, and the station will come off looking bad. So the general manager has to be able to make them work together and like it. When one department starts on a particular approach, s/he has to make sure the other departments know about it so they will be able to work with, instead of against, the new effort. Suppose a TV news department discovers a documentary on the history of the city is very well received. The program department may need to put a director on such a series to work with a producer in building several shows. The promotion department will want to get out ads to let people know more such shows are coming.

The sales department may need to know so the salespeople can talk to sponsors about paying for shows as popular as these will be. The general manager is not, however, a glorified gossip center, telling all the departments about the new shows.

S/he has the ultimate responsibility to decide to go ahead with such a series, and s/he then tells the others of the future programming and asks their support for the venture.

We can say, then, that the general manager is responsible for the direction the station takes. In TV, if s/he feels the sponsors will pay for more situation comedies, s/he talks to distributors about buying such shows to run on the station. In radio, if s/he feels a change of format to Golden Oldies will up the audience, hence the revenue, s/he starts the changeover.

If s/he is interested in a prestige image, s/he may decide to use the station to back a community effort to build a new auditorium for the symphony. If s/he thinks the news department will be the most effective means of building a good image with the audience, s/he will emphasize support for news.

It's the general manager's concept of what the station should be that determines how the rest of the station acts.

Yet, it's unfair to say s/he does this arbitrarily. In most cases, s/he talks to the department heads and gets their ideas.

S/he will discuss various approaches with them and will consider their ideas. S/he will listen to the changes they suggest, and their reasons why those changes should be made. S/he and the department heads will also consult the rating books to find out what they reveal about the makeup and size of their audience at various times. The rating books have become one of the most basic tools used at a station by the general manager, the program director, the sales manager, the promotion manager, and the news director. Others use the books as well, but these people are guided by them almost daily. These books are one more factor taken into account in this decision making process we're into now. Whatever the final decision is, it will generally be a combination of ideas about the station based on ratings statistics and reflecting several attitudes about what the station ought to do. Tyrants still exist in the world, but general managers are seldom included in that category.

The general manager's overriding concern, of course, is that the station show a profit. Without that, the station cannot stay on the air. So the bulk of what the station airs has to have sponsors who pay enough to cover all expenses and leave a little left over. The manager has to worry about the tape recorders blinking out or the cameras breaking down and needing repair, the salaries going up, the next union contract negotiations, and a million other financial details while at the same time trying to figure out just what to do to get more money from more sponsors. S/he wants to give the public the programs they want, the sponsors the low cost per listener or viewer that they want, and the profits necessary to meet expenses. So quite often, the general manager advances by way of the sales department. S/he may have been national sales manager be fore becoming general manager, so s/he understands the problems with money.

So here is a person concerned with finances, station appearance, the performance of everyone at the station, and who needs the diplomacy to make everything run smoothly. What training does s/he have to get to this position? Primarily, s/he's worked at stations for quite a while. S/he's proved some expertise in a particular position, such as sales manager or program director, and has demonstrated an ability to work with and manage people. Beyond knowing financial matters or having production skills, s/he must understand psychology.

S/he knows the theories of what makes people tick, and s/he's kept his or her eyes open to see how various situations actually work out. S/he knows something of management theory and how to organize people effectively. S/he knows something of sociology, too, because that also deals with how people function together. And, believe it or not, s/he knows quite a bit about the use of the English language. S/he knows deep inside that s/he has to be very careful about what s/he says or writes because s/he's involved daily in convincing people to do or not do something. Since language is the major propaganda weapon to do that convincing, s/he pays a lot of attention to his or her English.

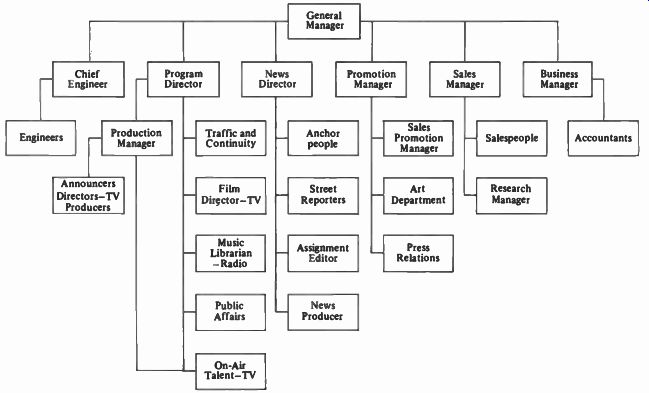

So this person has a variety of skills broader in scope than the specific ones demanded of the people at lower levels. We need to look at these other people, their responsibilities, and their departments. First, let's look at FIG. 1, an organizational chart, so you can see who answers to whom. Then we'll go on to some details about the responsibilities of all the people at a station.

FIG. 1 An organization chart

STATION PEOPLE--THE PROGRAM DIRECTOR

Other than the general manager, the program director covers more areas than any other person at the station. As the title suggests, s/he is concerned about the programs the station airs. S/he spends a great deal of time determining what pro grams will run, when they will run, and in what order. S/he talks to the research director, the sales manager, the production manager, and in TV, the film director to get information about programs. S/he discusses public affairs programming with the news director and the public affairs director. S/he surveys the population of the region the station covers to discover what they want to see or hear. S/he studies the ratings books to see what the population actually did watch or listen to. Then s/he takes all this information, passes it around to the general manager and all others who may be in on the decision process and makes recommendations as to what programs should go on the air. Let's see if we can get a clearer idea of what s/he does by looking first at a television program director and seeing how s/he would handle three different types of shows, then we'll consider a radio program director and ex amine what s/he would do with a format change.

Suppose it's the month of April and the TV program director is trying to choose new shows to run on the station next fall.

First, a movie distributor has a package of twenty-six different movies, only ten of which are really very good, but the price is low. Next, a local group has submitted a proposal to the program director for a half-hour show discussing the problems of the large Siwanese population of the area, which is to be videotaped in the studios. Finally, a syndicator has given an option to buy a brand-new, hour-long variety show, formatted like the "Tonight Show," available on videotape. What will s/he decide to do? Let's take the movie package first. S/he would talk to the film director to see if any of these films have been run in the area recently, if they are available in better packages, and if they were well or poorly received when they came out in movie theaters. If some of the movies have run in other markets, s/he will check with the research director to see how well they did, whether or not they had a large audience, whether they appealed to a special group like children or women over fifty or whatever, and if the best ten are new enough to pull good ratings during the ratings periods. S/he would look over a synopsis of the plots to see if any are un acceptable to the station. S/he would talk to the sales manager to see whether s/he thinks it would be difficult to sell these movies to sponsors, because if it is, that ends the matter right there.

S/he knows s/he will run the best movies during selected times, generally during the four weeks of a rating period. S/he knows s/he has three major rating periods in which s/he must run the strongest material so as to get the best audience possible. These periods are November, the end of February and the first of March, and the month of May. That's twelve weeks, and s/he only gets ten strong movies in the package so s/he has to decide what ones to repeat, and whether the package is worth what s/he will pay when there may be other good packages that offer twelve strong movies. Finally, s/he simply has to sit down and decide whether or not to buy the package.

If the film director says the movies have done well, especially the ten strong ones, the research director says they get big audiences, and the sales manager says s/he can sell all twenty-six tomorrow, then the program director has no problem except to decide in what order to run them. However, things are seldom so easy, and s/he makes tough decisions on almost every movie package. But once s/he decides to take it, s/he goes back over the synopses of plots, the lists of stars, and the ratings the movies got before and figures out when each one will run. Very likely, s/he would pick a strong movie or two for the first two weeks of the new season. Then s/he might run four medium-strength ones before the rating months of November. That's when s/he will run four strong films. Next s/he throws in the complete losers, saving four more strong ones for the February-March period. By the end of that, s/he used up twenty-four of the twenty-six movies and has shown all ten of the strong ones. S/he might go back to the medium ones and show those four again, then the two new films, then go into the May rating period with repeats of the September and early November strong films. That is also part of the decision process. Will scheduling like that work out? If it won't, s/he may finally decide against buying the package. Sometimes s/he may want just to flip a coin.

Now, what about that local show? First of all, s/he needs to know the community well enough to know if there really is a large enough Siwanese population who will care about a show on their problems. S/he will talk to both the news director and the public affairs director to get their opinions of the position of the Siwanese in the community. If s/he finds this group does indeed exist and care about such a show, s/he will want to talk with Siwanese leaders to find out what they think the major problems are. If there are no hot issues, perhaps there is no need to do a show. If there is sentiment against "outsiders" trying to poke their noses into Siwanese problems, the station would be better off dropping the whole project. But if there is concern over problems of the Siwanese group, per haps the station can render a public service by creating a series to discuss them. The next step, then, would be to find a Siwanese capable and willing to function as the producer of the show. This producer will have to arrange for guests, organize topics for discussion, and work with station personnel to create an interesting and well-done show. Let us suppose there is such a producer. Next, the program director must talk with the production manager and members of the production department to see who can work with the producer to direct this show. Also, s/he will discuss with the production department the various ways the show can be presented. Will it be a talk interview show? Will it be dramatizations of various problems? Will it be largely shot on film on location and narrated by someone from the studio? Once these topics are decided, generally with the producer's advice and always within the limitations of the station's capabilities in both money and facilities, the program director will meet with the producer, the director, and the staff they collect to make sure the first few shows are going smoothly. S/he will also meet with the production director to see if the studio time and facilities which can be made available are adequate to do a good show. Then the only remaining problem is deciding when the show can run. S/he needs to schedule it at a time when the Siwanese can watch.

Yet they are probably just as interested in seeing their favorite shows at regular times as the rest of the population, so s/he doesn't want to run it in place of the most popular situation comedy the station carries. S/he pores over the schedule and eventually finds a place. Too often it is at 6:30 Saturday evening or at 10:30 Sunday morning. But s/he does eventually find a place and then turns to consider the syndicated talk-variety show.

Here is a show s/he can look at, check out what the star has done before, and what other shows the producers have had. If they all have good "track records," that's one step in the show's favor. S/he can't check what the show has done in other markets because it's brand new, but s/he can check on how similar shows have done before in this market, and that can be very helpful information. Maybe the community turns away in droves from this sort of show. That would settle it; s/he wouldn't touch the show. Maybe there are millions yearning to see something like this. In that case, s/he buys it. Mostly, however, s/he will encounter a middle ground where some similar shows did well and some didn't. So s/he looks around at the schedules of the other stations. If they are each running shows like this, s/he will decide not to chance another one. But if none has such shows, it might be a good bet. Also, as with the movie package, s/he will check to see how easily the sales manager thinks s/he can sell the show. For the public affairs show s/he didn't care, but from this, s/he is trying to make a profit. Then s/he will decide whether s/he thinks it is a good show. That doesn't mean she wants to watch it, but that s/he thinks most people will want to. That's an educated guess, and it's the good program directors who guess right most of the time. If s/he does decide to buy it, s/he faces the same problem of deciding when to run it. Perhaps s/he wants to get the housewives to watch, so s/he shows it from noon to one. Maybe s/he wants to build the late afternoon audience, so s/he puts it in from 4:30 to 5:30. Maybe s/he wants a late night show and so puts it on after the late news. In any case, it runs five days a week, and is referred to as strip programming. The show is stripped in every weekday at the same time.

Now, let's turn to the radio program director. Generally, s/he has fewer programs to deal with than his or her television counterpart. Most radio stations have a particular format that runs all day long and doesn't change-it's Top 40, Country & Western, Beautiful Music, or all talk, etc. That means most of the programming is done with a DJ and a stack of records.

But "most" isn't "all." At various times, the station will still run special programs for special interests. The most obvious break in the routine is news. Generally every hour the station will have some sort of news report. These are quite often simply a matter of the DJ reading the copy that has come in over the news wire machines. But once in a while, perhaps during evening drive time, the station will provide something a bit more complete. This may be a ten- or fifteen-minute report of local, national, and international news, plus some sports, plus a weather report. Perhaps the station may even have a couple of reporters out around town who have gotten interviews on tape during the day, and these will run in this newscast.

The timing and complexity of this newscast are partly the product of the program director. Although the news director is responsible for the daily production of this newscast, it's the program director who decided in the first place that the whole thing was a good idea, and fit its particular time slot. Besides news, the program director may arrange for other specialty programming. A church service heard every Sunday morning is an example, as is a half hour every Saturday night devoted to the local garden club. Every group or special interest in the community may be the source for a special program which the program director may decide to use. Part of the job is to decide which groups deserve air time and then to find a place for them on the schedule. S/he'll leave it up to the news and public affairs director to contact the group, organize the program, and oversee the weekly production.

But suppose the station decides to change its format. Sup pose the station has been running Golden Oldies and finds the audience shrinking away to nothing. It's time to switch to a more popular music style. The program director takes a good, hard look at the market and at what the other stations are running.

S/he checks the ratings books to see how well they are doing.

S/he sees what styles are popular and are working. S/he checks to see if there is room for another station to get on the band wagon or if the audience is already so split up that s/he would be better off going for the second most popular format, or even the third. S/he checks to see if some formats draw only old people or young children. Neither have much money to spend and are thus hard to sell to sponsors. Once s/he settles on a popular format that draws the sort of audience s/he wants, s/he starts figuring out what the station needs. New records, new jingles, new intros and closes, new approaches by the jocks. S/he talks to the promotion manager about how to let everyone in town know something new is coming on the scene. It's almost like deciding to become a different person; all the major aspects and little details become different, and feel strange for a while. Eventually, though, the day comes, and the station goes on with a different sound. Then all the program director has to do is sweat until the rating books show whether or not the audience likes the change. If they don't, it's time to try something else.

These are some of the things program directors go through in deciding on programming for the stations. What does s/he need to know for this job? The program director should, like the general manager, have a working knowledge of psychology. S/he has to deal with people both inside and out of the station and get them to work together to produce programs s/he can air. S/he has to know what sorts of programs appeal to the interests and desires of the audience. All of this takes a knowledge of people. S/he also needs to know economics. If, in television, s/he buys a film package, s/he knows how much that costs. S/he also knows how much the rate card says the sponsors will pay to include their messages in a showing of the films. But s/he needs to know enough economics to figure out the hidden costs of running such a film and thus to figure out whether or not the rate from the rate card is high enough to cover expenses, plus make a little profit. If there's no profit, or perhaps even a loss, s/he'll need to buy a cheaper film package. S/he also needs to know enough about mathematics to be able to work with the statistics of the ratings books. A change of a rating from 12 to 13 means a lot more if that one point represents 100,000 people. S/he's got to be able to figure some CPMs, plus a few dozen other simple mathematical maneuvers--simple, but important. Then s/he needs to know the skills required in production. How can s/he develop a new show if s/he has no idea of whether or not the studios can handle the program's demands? S/he may not be a super-whiz-wonderful producer, but s/he needs to know the limitations imposed by mike placement or chroma key.

Now that we've seen what the program director does, a little of what s/he knows, and who the people are s/he works with, let's take a closer look at the sections of the department s/he works and consults with. Because of the responsibilities of this department, the following people will generally be under the program director: production manager, public affairs director (who in radio is generally also the news director), in television the film director, and in radio the music librarian.

the traffic department One other segment under the program director is the traffic department. After all the decisions have been made as to what shows will run and at what time, someone has to make up a chart every day of what runs at what times. This chart, as we have already discussed, is called the station log; and it lists every program, every commercial, every ID, and every other program element that goes on during the broadcast day. The people who make up this lengthy and exhaustive log are in the traffic department, presided over by the traffic manager. Ultimately, every program element has to pass through the traffic department, even if only in the form of a title on the log. the music librarian Another person from our list is the music librarian. This position varies in importance and even in organizational position from station to station. Sometimes the music librarian is under the production manager and is responsible for what are essentially the functions of a file clerk-keeping the records cataloged so they can be found and keeping them in good condition so they sound right on the air. New records coming in go to the librarian to be filed, and old records that have been played go back for re-filing. In other stations, this person is part of the team that listens to every record and evaluates each one to determine what will or will not be played on the air. For ex ample, a station running a Beautiful Music format might get an album from a major singer but decide that cuts 2 and 4 on side one and 3 and 5 on side two are just too upbeat for the soft sound they want to broadcast. The station team that makes that decision might include the program director, the jocks, and sometimes the music librarian. This decision of play or no-play by the major stations in major markets, primarily in Top 40 formats, is of vital importance to record companies. If a station decides to play a cut, or single, the sales of the record may go way up. A no-play decision, however, may keep sales in the cellar. So being part of that decision-making team can be a very important position at a station.

The film director

One further step back on our list brings us to the film director.

Obviously, the feature films which the station runs will go through this department. S/he will be responsible for the ordering, receiving, checking, and shipping out of these films, plus the cataloguing and storing of films which the station owns outright. It is the people under the film director who decide where the breaks can be made in the films for the insertion of commercials. They are the ones who cut, splice, and edit the films at the places they have chosen for such commercial insertions. But there are many other films which come to a station which must be handled by this department. Many commercials are sent out by advertising agencies on 16-mm film. They must be stored and catalogued so they can be found readily for repeated showings. Finally, they must be returned or disposed of when their usefulness ends. But besides film, programs or commercials that are on videotape are handled by this department. The processing is much the same, but the material they work with is videotape instead of film. The film department handles a video cassette instead of a film reel. That's the only difference.

As well as handling the flow of films and videotapes, the film director quite often views programs to form an opinion of their acceptability for airing by the station. If s/he finds the content offensive, s/he will suggest to the program director that the program be excluded from possible scheduling. S/he also maintains contacts with various film distributors and keeps abreast of current offerings of film packages. S/he maintains books and catalogues which show what is available and de scribe the films in terms of stars, critical reception, and plot outlines. S/he tries to know as much as possible about films available for television.

the public affairs director Next, let's discuss the public affairs director. As all stations are required to operate in the public interest, convenience, and necessity, it is mandatory that a station pay attention to the particular demands of its audience. It's the public affairs director who keeps tabs on those demands. S/he finds out what people in the community are concerned about, what approaches they are taking to solve their problems, and who the leaders are for the various groups. S/he establishes lines of communication with these leaders and works with them to further their aims by appropriate use of the station's facilities.

The public affairs director has a very delicate position because there is often a good deal of controversy surrounding some groups, and s/he wants to be perfectly fair to all factions. S/he can't, therefore, take sides or exclude any one group. S/he has to be quite a diplomat as well as being a responsible broad caster. S/he works closely with the news department of the station, because many public affairs activities come from the forefront of community actions. And s/he often is the one who initiates program ideas by locating a problem, figuring out a program format to handle the community needs, and going to the program director to discuss the ideas.

the production manager Finally, let us discuss the production manager and the production department. The production manager schedules all studio time, all crews, in TV assigns all directors, and in radio schedules the shifts for the jocks. S/he makes sure each program done by the station personnel has adequate studio time and as much rehearsal time and post-production time as possible. In TV, s/he judges the capabilities of the directors and assigns them to shows which best utilize their talents. S/he tries to build good crews for the directors to work with by recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of each member of the crews. S/he expects the tensions of production to produce friction, and s/he tries to sooth ruffled feelings. S/he, like the public affairs director, is in great part a diplomat. But among the more formal duties is the final say on the technical quality of the station's productions. S/he is also, in many ways, responsible for on-air talent. S/he may schedule the shifts for the booth announcer and handle details like vacation schedules and replacements for the host of the afternoon movie. But s/he doesn't do this alone. The performers have a large impact on the quality of programming, so the program director makes some major decisions here. S/he may decide a woman's voice works best for late afternoon and early evening announcing from the booth. S/he'll tell the production manager, who then does the specific scheduling. Likewise, the selection of a host for a movie is a programming decision carried out by the production manager but not made by the program director. Of course, the production manager works closely with these people and makes sure they keep their work up to high standards so the program director gets what s/he planned on. The production manager also keeps a sharp eye out for sloppy production and insists it be corrected. In radio, s/he judges the best voices and best styles for various times of the day. S/he works with the station's producers to get clean, polished shows. If outsiders are chosen by the program director as producers, s/he works closely with them for the same reason. S/he can put more pressure on the station's own producers to do things right, but outside producers are often chosen by the program director because they represent a group s/he wants on the air (as for a public service show) rather than because they are knowledgeable about radio. So it's up to the production manager to keep their shows up to the station's standards.

S/he advises the program director on the availability of studio time and personnel to handle new program ideas. S/he needs to know how to handle an infinitude of production situations so as to create a good show. S/he needs to be creative and imaginative so as to impart a sparkle and incisiveness to the station's productions. Because s/he is so directly involved in the look or sound the station presents to the public, s/he is quite generally consulted in the decision-making process of programming.

These, then, are the people who work with the program director in determining what goes on the air and what rep resents the station in the public's mind.

STATION PEOPLE--THE SALES MANAGER

The sales department generally has a national sales manager, a local sales manager, and several salespeople. As the station gets smaller, some of these positions may be combined in one person, as in the common situation where the general manager of the station is also the national sales manager. But suppose we walk into a fairly large station with an appointment to see the national sales manager (who is not the general manager) to ask him a few questions.

Secretary: May I help you? Us: Yes, we have an appointment with Mr. Nat Sales at ten o'clock.

Sec.: Mr. Sales is still in a staff meeting, but he should be here shortly. Would you care to wait? Us: Yes, thank you.

Sec.: Mr. Sales will see you now. Follow me please.

Us: How do you do Mr. Sales. We're here to ask you a few questions about your department.

N.S.: Fine, that's fine. Just sit right down and I'll see if I can fill you in. We have a fine group of boys here who really know their business, and I'm always glad to talk about them. Would you like some coffee? Us: No, thanks.

N.S.: You're sure now? Mary, bring me a cup please.

How about a Coke? Tea? Us: No, thank you.

N.S.: Well, what's first? Us: Can you tell us what your position is in the organizational chain here at the station? Who's over you and who's under you? N.S.: First, of course, is the general manager. He's over me just as he's over all the departments. So I'm on a par with the program director, the promotion manager, and the news director. Oh yes, the chief engineer and the head accountant are also department heads, but they are service departments rather than being involved in our programs, so they tend to slip my mind occasionally. They're both fine people, you understand, but I just tend to think in terms of the programs and the schedule and things like that, so I forget areas outside of that.

Now as to those under me, I have a local sales manager and four salesmen, plus the secretaries and clerks.

Speaking of clerks, let me include the research director.

He works with the ratings books and does a lot of number work, so I guess you could call him a sort of clerk. And that's my staff.

Us: Let's take those people one at a time. How about the research director? What does he do for you? N.S.: Well, when the ratings book first come in, he sees how we stand in relation to the competition. Then he figures our CPMs for the local shows. You know, the cost of a spot divided by the number of thousands of people who were in our audience at the time the spot ran. There's a lot of information in a rating book. Women, men, teens, children, people over fifty, you name it. He figures out the CPMs for each group. It's a lot of numbers work, but it tells us if we can sell a spot that's more effective than our competition.

Even if our rate is higher, so long as the spot gets to more people, it's cheaper per person. That's what the CPM will show.

He'll also figure out some packages for us. For example, in TV that's a combination of several programs we want to sell, usually with at least one dog of a show we have trouble selling by itself. If he ties it up with three or four shows we can sell easily, then we get some spots for it as well. The problem is to take a dog show, which of course won't have much of an audience, and find other shows with high enough audience sizes so the overall CPM is still good.

Other than just numbers, he'll take a good look at the audience compositions and tell us if we have a strong children's show followed by something for the senior citizens. That's what we call bad audience flow. The first show doesn't deliver any viewers for the second show. So our research director will suggest we either follow with a show for people in their late teens or early twenties, or replace the children's show with one for regular adults. But that gets into programming, and not sales.

Us: Does sales get into programming?

N.S.: You bet it does! I'll scream bloody blue murder if they try to put in some complete loser. They may think it's a great show, on a par with Shakespeare, but if I can't get a sponsor for it, they better junk it or think of becoming a nonprofit organization. Sure, I like a cultural show as much as the next guy, but I make my living out of the popular shows.

Us: Are you saying cultural shows aren't popular?

N.S.: All I'm saying is the heavy dramas and documentaries and symphonies draw very small audiences and can't be sold for very much money. And without the money, this station or any other, will go out of business. Sure, we will run an occasional drama or ballet or documentary, but the bulk of our schedule has to have big audiences.

Us: So you do argue against such shows at programming meetings.

N.S.: As regular parts of the schedule, yes.

Us: Perhaps it would help if you would explain just what the arrangements are by which you take in money.

N.S.: Well, first of all, we get money for the commercials we run.

They can run either in station breaks or during the shows we put on. For our radio station, that accounts for practically all of our revenue. We do take a news feed from a network every hour, and the network pays us to run their material, including their commercials for people like Colgate or Plymouth, but most of our income is from our local spots. Now in television, the network is a different story because they provide us with shows through most of the day. We carry programs from them in the morning up till noon, from 1:00 to 4:00, and then from 8:00 till 11:00, plus the network news at 6:30. All the other times are ours. We cut out a few network shows because we can run our own shows in the time periods instead, and that makes more money for us. And just like in radio, when you carry a network show and its commercials, the network pays you for each commercial you carry, but at only about 15 percent of your normal rate. So if you put your own show in there and put in spots for some local advertiser, you get 100 percent of your spot rate. Of course, out of that you have to pay for the production costs of the show you run, and if the show isn't popular, you can't charge much money, and so it sometimes isn't worth doing. But generally you can make more money that way. The networks expect you to do this a bit, but if you start preempting everything, they really get upset with you and give you a hard time.

So in brief, you can say we get money for the spots the station runs, and they're paid for by the particular advertisers; and we get money from the spots the network runs, and they're paid for by the networks. The networks, of course, get paid by the sponsors or they wouldn't be able to afford to pay us.

Us: Now how about the other members of the staff you mentioned?

N.S.: Let's see, I mentioned the local sales manager and the salesmen, I think.

Us: Right.

N.S.: The local sales manager handles a great deal of the advertising this station runs, but not all of it.

Of course, he doesn't handle relations with the networks about the spots they run. I do that. But there is another part of the station advertising he doesn't handle and that's the national sales. What he handles, see, are the local boys, the car dealers and the department stores and the furniture stores right here in town. When we make a deal with a national company like Coke or Ford or Ivory Soap, I'm the one who handles that. Those companies buy some of our time directly, instead of getting it indirectly by buying through the network. Sometimes it's because they want time periods the networks can't offer. Sometimes it's because they don't want to buy all the stations the network represents so they deal with just a few individually. In any case, I'm the guy who works out those deals. The local sales manager just sticks to the local market. And after all, that makes up the bulk of our particular station's advertising. He and the salesmen maintain contacts with all the owners of the stores and businesses, figure out what sort of schedule of spots will offer the best deal, try to undercut the competition, and so on. They really know the local market conditions, who's doing pretty well, who pays his bills, and so on.

Us: You keep referring to the men on you sales staff.

Are there any women?

N.S.: No, there aren't.

Us: Why not?

N.S.: Well, there aren't any who have applied who are qualified.

Us: But don't you hire and train any people?

N.S.: Well, yeah, and I guess we're going to hire some women as salesmen, I mean salespeople, sometime soon.

Us: Do you think they will do pretty well?

N.S.: I don't know. I guess so. A couple of our competitors have women on their sales staffs and they seem to be working out pretty well.

Us: How do you determine how much your spots will cost?

N.S.: That's sort of an educated guess. We all get together and decide how much we think the market will bear. We work on the basis of the cost of a thirty-second spot and the various times of day. In television, if it's early morning, the spot will cost less than at 8:00 at night. In radio, drive time costs more than 2:00 in the afternoon. A longer spot costs more and a shorter one less, of course. And if a sponsor buys a lot of spots, we give him what we call a "frequency discount." The more he buys, the cheaper each one is. But it all boils down to a guess as to how much we can get people to pay. If the audience of a show goes up, we can get more money for it. But if it goes down ... We have some other charges too, like production charges, and we set their rates the same way.

Us: Production charges?

N.S.: Yes, if we make the commercial here at the station, we charge for that. If the sponsor gives us the commercial on film or videotape or audio tape, we don't have the hassle of making the things ourselves so there is no production charge. But if you have to call in a director and a crew or a jock and an engineer to make a spot, the sponsor will have to pay for it.

Us: Suppose a sponsor isn't watching or listening at the time his spot runs. How does he know it really got on the air? N.S.: Here at our station, we have the announcer on duty keep a record on the log as to whether or not the spot ran.

If it runs, he writes in the time when it started and the time it ended. The sponsor just has to take our word, or really the announcer's word, that his spot did run.

Us: What happens if, for some reason, the spot doesn't run?

N.S.: Then we give what's called a "make-good." We will run the spot some other day during a comparable time period and, of course, will not charge him anything extra.

Us: Did you have any special training for your position?

N.S.: Well, I worked as a salesman for quite a while, and that's certainly a place to learn a lot. I learned how people react to various things, what makes them respond well to some approaches and poorly to others. You could fairly call that psychology, I think. Then I also learned about economics. After all, that's what I'm dealing with. I need to understand the business conditions so I can tell when to try for a sale with a car dealer and when to approach a department store. And believe it or not, I've needed to be fairly capable with some simple math so I can deal with some of the statistics of a rating book. I've talked about having 28 percent more women eighteen to thirty-four in our audience and have convinced people to buy spots because of those statistics. That's simple math, but useful. But the main thing is what I mentioned first-learning how people react. I started out in a small station in a small market and called on every prospect I could think of. I met all types and tried every approach I could think of. That was probably the most valuable education I ever got.

Us: Mr. Sales, we can't think of anything else we would like to know about your department. Thanks for spending this time with us.

N.S.: It was my pleasure. Be sure to come back if you think of anything else you'd like to know.

STATION PEOPLE--THE PROMOTION DIRECTOR

Would you buy a triplex cam spanner? Maybe you would if you knew what it was. How do you find out about it? Most of us get the bulk of our information about products from advertising. You see a spot on television which shows the product, what it does, where it's used, and what its good features are. That way you know whether or not you have a need for the product and whether or not you like that particular brand. The advertising process in broadcasting is the same to get you to watch a new television show or listen to a new radio show. You have to be made aware of what the show is so you can decide if, for in stance, you want to watch a medical show and if so, whether or not you want to watch that particular one (Dr. A instead of Dr. B). Making you aware of shows is the job of the promotion department.

And as with other products, the promotion department will advertise on the air. That, after all, doesn't cost the station anything as it's their own air time. So the promotion department will come up with short spots, very much like commercials, which use a funny or dramatic or interesting section of a show, then announce when the show will be on and then ask you to watch or listen to it. Also, on television, the ID's may be used to show a title and a time for a particular program.

Or you may just hear the announcer's voice over the ending credits as he asks you to tune in to a particular show at a particular time. All these spots are created by the promotion department and fall in the category of on-air promotion. They will be written and created by the promotion staff, then produced by the production department of the station.

You may also hear announcements on radio asking you to watch a particular show, or see spots, or "promos," on television asking you to listen to a particular station. This cross plugging happens particularly if one company owns the television, FM, and AM stations as a combination. These cross plugs, believe it or not, are not for free. However, since all three are owned by the same company, a pretty easy arrangement is made for trading time for time, and no money changes hands. Mostly, just bookkeeping details are involved. But if a television station has no radio station as part of the group, it will have to lay out hard cash to a local radio station to carry the announcements, just as the used car dealers and departments stores do. In any case, it's the promotion department that makes the deals and writes the spots and sees that they get produced.

But there are other advertising media, and promotion uses them all. The newspapers are a prime source. Not only will newspapers carry ads which the promotion department places with them, they will often have a radio-television columnist.

So in order to be mentioned (and favorably) by this columnist, the promotion department has to keep on good relations with him or her. That may include remembering birthdays and sending Christmas cards or presents, but more important, it involves being sure the columnist has the information s/he needs when s/he needs it. Schedules go out once a week showing what will be aired in about two or three weeks. Changes are announced as soon as possible. Specials are discussed and explained early enough for the columnist to write about what's going to happen. Sometimes, in television, advance showings are arranged so s/he can see a show before it's aired, and can thus write about it. Generally, though, columnists hold comments until after air time. That saves the station getting a bad review before anyone else has a chance to see the show. If that's the case, the advance showings are just for the convenience of the columnist, and that's another way to stay on good terms.

The paperwork that goes with advance schedules; changes; or information on specials, stars, or new shows is all handled by promotion. Most of it is written in the department. Tele vision networks send out information on the content of every prime-time show, every episode, and it's the promotion department that takes this, boils it down, and provides a summary to newspapers. Then with a change in the schedule, promotion prepares extensive information on the format of the new show, the stars and what they have done before, the producers, the director, and just about anything else they think might be interesting to a columnist. For radio, the promotion department is totally responsible for writing up all the information. If a new DJ comes on, promotion writes up a biography for the press. If a contest starts, promotion writes descriptions of it.

Since networks are such a small part of radio station activities, the promotion department carries a far heavier burden.

The ads which newspapers run for the station may be designed in the promotion department, or they may be handled by the promotion department after being received from the net work. In either case, it's up to promotion to get the ads to the papers with the proper identification as to when the ad runs and how often. The promotion department will also handle the bills which the newspapers send out for having run the ads. If the ads were totally a creation of the particular station, the cost comes from the promotion department budget. But if the ads are for network shows, as is often the case at the beginning of a season, the cost will partly be paid for by the network, and that contract is negotiated by the promotion department, generally on a half-and-half basis.

Besides newspaper ads, there are other media which can be used. Billboards may carry advertising for a particular show.

Cards on the tops of taxis can be used, as can cards inside and along the sides of buses and subways. Magazine ads are some times used. For some shows, the programs of musical events or plays may carry station ads. A show for a young audience might be advertised in a program of the performance of a popular music group. A show after an older musical audience might be advertised in the program of the symphony. In some cases, direct mail might be the answer, with the advertising piece mailed directly to the "boxholder" or "occupant." You might even find a sheet of paper stuck in a bag of groceries by the sacker, especially if the station is promoting a show sponsored by that grocer. Almost all ways to get the public's eye-sky writing, men on stilts carrying sandwich boards, blimps, handouts on street corners-have been used at some time or another by a promotion department. The point is to make people remember a show, a time, and a station. A good promotion department comes up with clever ways to make people remember. If people remember, more will listen to or watch the show than would otherwise. And if more listen or watch, the ratings will be higher and the station can charge more money for a spot within that show. That justifies the money spent by promotion.

Speaking of money, let's see how the promotion department functions in relation to the financial hub of the station-the sales department. Obviously, the salespeople are out talking to sponsors trying to get them to buy spots in shows. But how do they present the shows? How do they get the sponsor to re member when the show runs? They take with them a schedule of all the shows and a program sheet which describes the show, the stars, the producer, the ratings, or whatever is felt to be important. These two items, the schedule and the sheet, are prepared by the promotion department. The schedule is designed and printed according to promotion plans to look good as well as to be informative. The sheet is written and designed to represent the show and hopefully present it in a good light.

All of this planning and design is done by promotion as a service to the sales department. Also, if there is something special the sales department needs, such as an overall presentation of the sales advantages of the station, the promotion department will come up with a series of slides, or a film, or a videotape, or a series of desk cards, or charts, or whatever is needed to make the particular point. Also, in television, the sales department often wants to introduce a whole season to the advertisers of the area. It's the promotion department that plans the presentation, organizes the party and the pitch, and carries the whole thing off. In a port city, the advertisers may be taken on an ocean cruise while the food and drink and new programs are brought around. In a smaller inland city, the presentation may be a buffet at the station and the showing of a videotape with information about the shows. But promotion handles it all. The sales department, then, turns to the promotion department for all kinds of sales support that can't be done by the salespeople talking to the advertiser.

The art department

One of the sub-departments one often finds in television promotion is the art department. After all, it is promotion that uses pictures and specific typefaces and graphics of varying sorts for almost everything it does. The ID slides, the billboard designs, the schedules and program sheets used by the sales people, the ads placed in TV Guide and in magazines and news papers, and a dozen other things need the specialized touch of a graphic artist. S/he has to know the specific requirements of the media-the quality of paper, ink, and typefaces and the tricks to make something inexpensive look good-and must have the ideas to create new looks and new approaches. Appearances go stale very fast in television, and each program or season has to have something fresh about it. The art director has to have enough ideas to make these things fresh. And s/he has to have these new ideas day after day, year after year. Be sides that, s/he has to design and build the sets used at the station. S/he will be responsible for how shows appear on the air. If the "Home Show" has a jumbled living room, the blame falls on the art director, just as the credit does if the news set is clean, functional, and attractive. The responsibility for the look, in sets, in logos, in print, in colors, and in overall design, is the art director's job.

the promotion manager That look, while created by the art department, has to be approved by the head of the promotion department, and that gives a hint of what sort of background the head of that department must have. The promotion manager needs to have a knowledge of graphic art so as to evaluate styles in ads or sets or bill board posters. S/he also needs a knowledge of advertising techniques. There's no point in creating a good-looking billboard if its message won't be effective. Furthermore, the promotion manager needs to know the production techniques of television, film, and radio. S/he will, after all, create promos in all three media. Also probably more than anyone at the station except for the news personnel, s/he needs to know English very well since s/he constantly uses words to convince people to join the station's audience.

STATION PEOPLE--THE NEWS DIRECTOR

In radio, news is often a small concern in the overall schedule.

The DJ on duty may merely read the wire copy that comes from the AP or UPI machines. S/he may go to network news on the hour, come back with a local weather forecast, and slip right back into music. Or the station may be a little more dedicated to news and have a news director and maybe even a reporter or two. They will rewrite the wire copy, but they will also go out around town to follow up on local stories. They will take a mike and tape recorder and try to get on-the-spot comments from the governor or mayor or whoever is making news that day. At demonstrations they will talk to members of the crowd as well as trying to interview the spokespeople on the speaker's stand. All this material will be hurried back to the station for those hourly newscasts. The result can be very fast reporting, probably faster than any other medium. A recorded phone interview five minutes before air time can easily go on the air, a feat difficult to match anywhere else. But still, unless the station has an all-news format, news is not a big concern at most stations.

In television, however, a local station builds its reputation more on its news department than on any other single thing it does. The programs, the specials, the contests, the personalities, and the publicity all have their impact, but viewers seem to build their impression of the sort of station it is by the people they see every night, sometimes twice a night, giving them the news. Since most Americans now get their news from television rather than from newspapers, stations are sure they reach a large portion of their audience through their news departments. Any one station, or any one news department may not reach a large audience, especially as large as a popular network show; but for day-in, day-out contact with viewers, news is vitally important.

anchor people Where does this contact start? What do you think of first when you think of the news of a particular station? Chances are you think of the people who are seen on the screen reading the stories. The anchorperson in particular is probably your first thought because you see that particular newscaster almost every time you watch and s/he seems to be the central point around which the rest of the news presentation is organized.

S/he quite often introduces the sports reporter and the weather person. S/he pitches to various reporters for their special stories. But the bulk of the news and the introduction of all the special reports comes from the anchorperson. Because of this central emphasis, that job becomes one of some importance within the news department. It's also a job subject to whims and fads. Sometimes the stations in a market will all be presenting pretty boys who only read. Then perhaps the style will swing to father figures who declare the news with authority.

Then, perhaps, the search goes on for a sex symbol who can also be trusted as an honest, working reporter. And so it goes.

But the job remains a central one, and one the news department worries about. With the right anchorperson, the audience will appear almost as if by magic. S/he sets the tone for the reliability and hard investigating which the rest of the department does. S/he may never hit the streets following down a lead on a murder, but the viewers get that impression from the best ones and transfer a belief in the anchorperson to a belief in the rest of the news staff and thus to the rest of the station. So the primary contact with the viewers is the primary concern of the station in presenting the news.

No matter how perfect this anchorperson is, though, s/he has to have news to give or people won't watch. That's obvious.

So s/he has to have help. S/he gets it from a great number of people doing a lot of hard work. These people include street reporters, film and videotape crews, film and videotape editors, an assignment editor, the producer, writers, and finally, the news director. The director is the head of the department, not the one who directs the news while it is on the air. That person is a director of the news, not the news director. But let's go on the way we started and see who's immediately behind the anchorperson.

Street reporters

First let's look at the street reporters. Their faces are also familiar to you, because they are the ones who go out to the State House to interview the governor or out to the fire to see what's happening. They show up mostly on film or videotape, as their story is done right on the scene. They have to show what's happened as well as tell about it, so they go wherever they need to for the report. Their day, then, is spent in traveling to newsworthy events and looking around and finding someone to talk to, or maybe in presenting their own analysis of the situation. Then they end up with some statement like "This is John Morris reporting from the scene of the Vendome Hotel fire." All this is on film or tape so a film-tape crew goes with him. The crew consists of generally one person, although it may be two. The film crew, or person, has the responsibility of lugging around all the heavy equipment, setting up lights if possible, putting the camera up on its tripod or on a shoulder, hooking up the mike, and checking to see everything is running properly. Then s/he cues the reporter, who faces the camera and says, "The first alarm reached fire station #28 at . . ." When the reporter and crew get back to the station, the reporter writes the introductory words to the story, and if the story was filmed, that film will now be processed. If the story was done on videotape, the reporter keeps the cassette handy until time for editing.

Let's talk about a story on film first, of a fire, for instance.

Once the film is processed, the reporter will sit down with a film editor and the two of them will look at all of it and decide what parts to cut out, what to leave in, and what shots of the burning building are best. They will have been given a time allotment by the assignment editor or the producer, and they know the film cannot run longer than that. So sometimes they have a lot of cutting to do. Sometimes they have to try to talk the producer out of a bit more news time, and if the story is important, they will get it.

If the story was shot on a video cassette, the process is much the same. Again, one of those two people, the assignment editor or the producer, will have given them a time limit. So the reporter will work with a videotape engineer to pick out the best shots and figure out the best sequence for the shots. Then the engineer will dub those over from the cassette to another cassette, or perhaps to a reel of tape, for play during the news. Now what of these other two people we have just mentioned? the assignment editor The assignment editor is the one who starts the whole news day rolling. S/he knows the city, the politics, and the important people. S/he senses what's important. S/he knows where to go for leads. S/he knows the layout of the town so s/he will know if s/he can send a reporter out with enough time to get back and write up the report for the newscast. S/he is, then, the one who sends others out on stories. S/he assigns what they will cover and where they will go. Without a good assignment editor, the news department will waste its time following up unimportant stories and will get only a few of the important ones. Because s/he should know how long it takes to get out, film a story, return to the station, edit the story, and write the lead-in, s/he can make the best use of the reporter's time.

The news producer

The producer starts to take over as the assignment editor starts to ease out. Their responsibilities will overlap for a while, as they both will be dealing with stories and reporters as they come in. But ultimately, it is the producer's decision as to what goes into the newscast. Needless to say, s/he takes advice from the anchorpeople, from his or her reporters, and from the news director. But s/he is the one who is responsible for pulling the pieces together for the cast. S/he decides which stories are to be read first, second, and so on. S/he decides how much time can be spent on the various stories. S/he makes sure everyone knows how much time remains until the news cast starts. S/he also supervises the writers and talks with them about what's coming in and what they're writing. It is the writers who get news from the teletype machines, which feed stories to the station from Associated Press or United Press International. These stories, of course, are generally of national or regional events, and the writers take this wire copy and rewrite it for presentation in the local newscast. The producer needs to know if important stories are coming in, or if long stories are showing up, or if the writers aren't getting enough written to fill up the time. The local stories are more important, but s/he keeps an eye on the writers for their essential contributions nonetheless. So s/he and the assignment editor are the organizers of the newscast. If they aren't good and they don't know where to send reporters and in what order to put their stories, then the news won't be very good.

The news director

It's up to the news director to be sure s/he has good people in those two spots as well as in the anchor position. The look of the news, the believability of it, and the thoroughness with which the staff covers local stories are all up to the news director. S/he has to know news and the essentials of news gathering so s/he can judge how well the reporters are functioning, how efficient the assignment editor is, and how skilled the producer is. This job, as with that of many department heads, is not so much to oversee the day-to-day production of the department as it is to establish the overall approach. If s/he believes the station and the public would best be served by nothing but local news, s/he may eliminate all national and regional stories. If s/he thinks more filmed or taped stories and more location work would give a better coverage of events, s/he may hire more film-tape crews and street reporters. If s/he thinks a regular series of investigative documentaries are an essential part of news, s/he may create a sub-department to produce one documentary a month. S/he is responsible for thinking about the quality of news, its presentation, and its production.

The news department

The news department occupies a unique spot within a station.

The news director is responsible to the general manager and to none other. The news department should never be interfered with by production, programming, or sales. News has to be unbiased and fair, or at least as far as is humanly possible.

Therefore, the news department must be rather isolated from the other departments. The content of the news is a forbidden area to everyone else in the station. A reporter must be free to talk about what s/he discovers, even if that discovery steps on important toes, so no one at the station should be able to refuse a reporter that right. So the news department must be free from production problems, sponsor complaints, and programming headaches. The news director must know how to intercept an attempt of an outside department or person to have an effect on news presentation, even if the attempt is made in all innocence. Not all stations follow this approach, and not all news directors are successful at intercepting, but this is the ideal. It's a credit to broadcast news that this ideal is reached in a vast numbers of stations. It's also a credit to news directors that they manage to uphold this ideal in so many difficult and varying situations.

STATION PEOPLE-THE EDITORIAL BOARD

More and more, stations are developing an editorial board as part of the station organization. It doesn't have quite the status of a department, and the members of the board generally cut across other department lines, having their primary responsibility in another area. But an editorial board serves as useful a function for the station as does an editorial writer for a news paper. The FCC believes editorials to be a good thing, helping to serve the public interest, convenience, and necessity for that area. So with that sort of prompting from the agency which reviews and renews their licenses, many stations have created editorial boards.

First of all, the stations select people from within the station. Second, they sometimes select people from outside the station to act as advisors. Let's take a look at the first situation.

Obviously, the general manager will be the head of the editorial board. Because the editorials will express station policy, they will often be given by the general manager on the air. Of course, not everyone at the station will agree with the editorials, but officially the station will take the stand expressed in the editorials. Since this is the case, the general manager, as the chief official of the station, presents them. It's entirely possible s/he doesn't agree with the editorial, but is expressing the view of the majority of the editorial board. Realistically, that seldom happens. If the general manager doesn't like the editorial, s/he doesn't give it.

The next member of the board is the program director. As the second most important person at the station, s/he has to be included. Also included will be the news director and the public affairs director. These four will quite often be joined by another member of the station, for instance the production manager or the promotion manager, so as to make five, an odd number, and thus avoid tie votes. These people will submit topics for editorials, and generally the public affairs director will write up a draft editorial. It also happens quite often that the one who suggested the topic will write the draft. At larger stations, quite often a particular person will be hired to write the editorials. This person becomes a member of the board and functions exactly as the others do.

Once a topic has been chosen, the board will discuss the point of view. They will decide what they want to say about the topic and what stand they want to take. They will decide how best to approach their point. Then a draft will be written.

The board will meet again to look over this draft, make corrections or changes, and approve it for presentation. Then the general manager, or sometimes another member of the board, will tape a presentation of the editorial. It will then be scheduled in whatever way the station has decided is appropriate. Some stations bury their editorials after the late-night news or in mid-morning. Some run them only one day. Some run the same one all week. Some include them in the early evening news.

All, however, invite response from people opposed to their stand, and all will give free air time to a statement in opposition.

Now, let's discuss the stations that include people from outside the station. The basic board within the station remains the same sort of thing we have been talking about. But the station, generally through the public affairs director, will invite various representatives of various groups in the area to become associates of the editorial board. Where the station board may include only four or five members, the associates may number twenty-five, thirty, or more. Obviously, they are not all consulted at all times. But when the station is contemplating a stand on a topic in which one of their associates is an expert, that person obviously gets called in. S/he then becomes part of the discussion process leading up to the recording of the editorial. For instance, say the station wants to tackle the corruption in City Hall. And say one of its associates has been a reform candidate for the office of mayor. S/he would be called in to give advice on what should be said. It even happens, in less explosive circumstances than that, that the expert will be the one to read the editorial on the air. And it's obvious, I'm sure, that these associates can contribute ideas for editorials even though the station has not specifically asked them to. This expanding of the editorial board will relate the station to the community in a number of ways, but it can also embroil the station in battling factions. It's a calculated risk many stations don't take.

Editorials in general are a risk. More and more stations, though, find the risk worth taking. Whether or not people agree with the stands taken, they at least feel the station is involved in what's going on in the community. And that sense of involvement goes a long way toward satisfying the requirement to serve in the "public interest, convenience, or necessity" which the FCC demands when it passes out licenses.

STATION PEOPLE--ENGINEERING

Broadcasting is a matter of machines. Of course, what gets done with those machines is far more important than the machines themselves, but you can't deny the value and place of machines. Without a functioning microphone, camera, switching console, or transmitter, the greatest ideas in the world won't get out of the producer's head. So no matter how creative and innovative the station's staff is, it must turn to the engineering department for essential help.

The chief engineer should know electronics both in practice and in theory. S/he's the one you go to when you want to know how to accomplish a special trick or to get the equipment to do a bit more than it's supposed to. S/he responds to techno logical challenges, and if s/he's good enough, s/he'll take a paper clip, some chewing gum, and a screw driver and convert the wastebasket into two color cameras, a double re-entry switcher, and an edited videotape machine. In other words, s/he knows the system backward and forward, can design electrical systems, can see how to improve the gear you have, and can figure ways to make it do things the original designers never dreamed of. S/he knows more than just repair, s/he knows how to pick engineers who can do more for you than just the routine turning of screws and checking of dials. And s/he's a good enough administrator to keep them all happy working together.

That's the ideal. Sometimes you're lucky if the chief engineer can walk through a door and chew gum at the same time. Sometimes you'll feel that way about the general manager too. And the production manager. And the program director.

And . . . So there will be problems. But remember your bad days when you can't sign your own name without misspelling it. So somewhere short of this ideal is the person you actually have to work with. S/he knows far more about the resistors and wires and circuit boards than you ever will, and s/he can do things with them you didn't think possible. S/he can help you in a dozen ways when you are faced with problems. If you are doing interviews at a roller derby, or taking the cameras outside, or trying to get a shot from above the action, or if you want a special arrangement for the election coverage, s/he's the person to talk to. Sometimes s/he will flatly tell you it's impossible. The path of wisdom is to believe that and find another way to do it. But always show a great regard for the care of the machines, and you will win any engineer's heart.

The machines, after all, come right after his or her mother in an engineer's affections.

Most of the engineering staff will be concerned with working on the machines to keep them in running order. No matter how new or how perfected a machine may be, it has gremlins and crotchets which cause it to slip into a rest just at the moment you need it. The engineers have to be able to slide a transistor in its side and get it functioning again. So much of their time is spent probing and correcting and rebuilding.

Then too, they try to prevent breakdowns from happening, so they continually go over equipment to see if they can spot a weak unit, or to make sure the entire thing is running up to its expected level of output. Cameras, if left alone, will slip from a clear flesh tone into bilious greens or outraged purples.