What does a broadcasting station, whether radio or television, have as its raw material? Time. General Motors can turn out a car-a solid, tangible item which exists even after General Motors is all through with it and has sold it. But a broadcasting station has time, and can fill it with a variety of things which exist only for a short while and then are gone forever. While there's a lot of time available to be used, it can only be used once. There's no way to reprocess yesterday's noontime. So the stations are in a perpetual scramble to fill that vanishing, yet plentiful, time with comedies and news and music and drama and movies and .. . All of these programs have to come from somewhere, and because there is so much time, there are a lot of "somewheres" providing programs. Since radio and television take very different sorts of programs, we can't say the same program sources work for each. So let's take them one at a time.

TELEVISION: NETWORK AFFILIATES

First television. Let's look at the NBC station in Two Whistle, West Virginia. At 6:45 every morning, they come on the air with a farm and market report, done by a sleepy reporter from their studio. At 7:00 they pick up the "Today" show, which is sent to them over a telephone line from a bigger West Virginia city.

That city got it from a telephone line from Philadelphia, which got it from a telephone line from New York City, where the program originated in a studio much like, but somewhat larger than, the one Two Whistle's farm and market report comes from. The telephone line, too, is like, but somewhat larger than, the telephone line you're used to at home.

So from 7:00 till about noon, with only a few breaks for station breaks and commercials, this local station receives and broadcasts programs provided by NBC. Some originate in New York City, some in Los Angeles, some are live, some are on film, and some are on videotape. But for Two Whistle, NBC starts them on the telephone line out of New York City all morning long. The noontime break is for news, generally, which is done by the local station. Also, some other half-hour program is run by the local station. This may be old shows of "I Love Lucy" or "F Troop." Then NBC starts in again with the after noon soaps and game shows. In the late afternoon, NBC stops and Two Whistle picks up again, once more providing shows like "Mike Douglas" or "Gilligan's Island," or maybe a movie with the starlet Narda Onyx. In the early evening, the station does a news show, then goes to NBC evening news. Once more the network shuts off, and the local station provides the evening edition of "The Price Is Right" or "What's My Line." After that, it's back to NBC for the prime-time shows. In the late evening, the network stops so local stations can do a half hour of late news. Then comes the "Tonight" show. After that, Two Whistle goes off the air because they figure all the farmers in the area are long since asleep and there's no point in showing anything.

So the station is off the air from 1:00 A.M. till 6:45, when the farm and market report comes on again. Out of a broadcast day of about eighteen hours, NBC provides Two Whistle with thirteen hours of programs. The local station has to come up with the remaining five hours each weekday. As we have seen, some of that time is filled with news done live from their studios, some is filled with films of old programs or old movie films, and some with videotaped shows like "Mike Douglas." The film or tape shows are sold by various groups which contact the station, so that's a matter of selecting what the station can afford and what seems likely to please a large audience. The news, of course, is a local product, done by reporters and news people hired by the station.

This is a basic station arrangement, filling its time in basic, standard ways. This station is referred to as an affiliate of NBC because they run the programs provided by NBC. But they don't run them for free. The station has to pay its reporters, directors, and secretaries, so almost everything it does is an attempt to turn a buck. You know they collect money from G.E. every time they run a commercial for one of the refrigerators. That's where the bulk of the money comes from, of course. Those spots, plus the ones for Brown's Hardware downtown, bring in most of the station's revenue. But they don't give away air time for free, not even to the network. Suppose NBC provides a half-hour program at night and has three commercials in it.

Two Whistle's rate for a commercial run at that time is $100 each. For three, that's $300. But because getting the programs is such a good deal for the station, they have agreed with NBC not to charge the full rate. They will take the program and the three commercials within it and only charge $30. If the station didn't take the program, it would have to buy one from some where else, and even though it could then get the full $300 for commercials, it would probably have to pay almost that much for the show itself. So taking the NBC show is a good deal.

The network is content too, because it can tell the sponsors of those three commercials that the audience for the spots is nationwide, even including Two Whistle, West Virginia. And the more people who watch, no matter where they live, the happier the sponsor is and the more he is willing to pay NBC. So NBC may charge $40,000 for one of those commercials, or $120,000 total, and then split it up among all its affiliates, including the $30 to Two Whistle. Needless to say, there is some left over for the network itself to keep and play with.

Network owned and operated

Affiliation has been such a good deal that lots of stations around the country have made similar deals with NBC, CBS, or ABC. These stations are all affiliates of one network or the other and carry the programs of their particular network choice.

The networks, as we have seen, make money out of this by keeping part of what they charge the sponsors. But they also saw that the stations were making money, so they decided they could make a bit more by outright ownership of some of the stations. The government stepped in here and ruled they could own no more than seven stations apiece, and of the seven no more than five could be VHF (that is, channels 2 through 13). But that's better than nothing, so the networks bought stations in major cities. These stations are referred to as the network 0 & 0 stations, which stands for owned and operated. Just like the station in Two Whistle, they carry the network offerings whenever the network sends them down the phone lines. And just like Two Whistle, they fill in the other times with material of their own choosing. Because they are in bigger cities and can make more money, the shows they choose tend to be newer and better. Also, they will produce a few shows of their own. That's an expensive proposition because you have to pay writers, actors, directors, scene designers, and a whole host of other people. A little station can't afford that sort of thing, but a big one can. So the network 0 & O's will slip in some shows of their own. They also run bigger, more expensive, and more elaborate news operations. They do several news shows each day and try to do news specials with some regularity. Again, smaller stations don't have the money for this, but a big station does. Also, even though these 0 & stations are run as separate parts of the network, they do keep the network's interests in mind. They will provide the network with news coverage of events in that particular city which the network can then use for its nationwide news shows. They will look for new talent to hire, train, and then pass on to the net work news operation. And they will keep their facilities up to date so the network will have good equipment to work with if it needs it.

So the network 0 & O's are just like the other affiliates, only more so. All the affiliates do the same sort of thing-take programs from the network, fill in the other time with shows of their own choosing, and get money by selling commercial time and by collecting from the network. The 0 & O's just have the advantage of being a little closer to the big money.

Group owned

If it's an advantage for a network to own a few stations, it ought to be some sort of advantage for anyone to own a few stations. And it is. If one station makes money, two stations ought to make about twice as much. And so on. This elementary arithmetic has caused some people to start buying up stations.

They run into that same governmental rule about no more than seven stations, but that can still be seven times as much in come as owning one station. So around the country there are companies owning several stations and running all of them in similar ways. These stations are referred to as group owned, since a group of them are owned by one company. Westinghouse, Corinthian, and Metromedia are some of the names of group owners. And like the networks, they try to get stations in the bigger cities. There's more money to be had there. Let's create a typical group situation, Rectangle Broadcasting, and see what the set-up is.

Rectangle owns a station in Boston, one in Pittsburgh, an other in Philadelphia, and the last in Washington, D.C. In Boston, the station is the CBS affiliate; in Pittsburgh, NBC; in Philadelphia, ABC; and in Washington, it has no affiliation. So the four stations have a wide variety of programs during the network hours. Since each is a separate station, even though they are owned by the same company, there is no need for them to all go with the same network. Probably, when the company was buying stations, they had no choice because it was only the CBS affiliate up for sale in one town and only the ABC one in another. So Rectangle bought what it could and now has a great variety of programming. But what of the times when the net works don't provide anything, and what about that one station with no network affiliation at all? As you might expect, each station does some news shows.

Each station also buys some old shows like "Flipper" and some old movies. But for a lot of those blank periods, Rectangle has the advantage of being able to deal from a central position.

That is, the company can buy "Bonanza" and show it on all four of its stations. Rectangle pays more for it than if it were buying for just one station, but less than if four individual stations were buying it. So the four stations get a good deal on a good show. Also, the station in, say, Washington may produce a pretty good game show. That station videotapes the show and sends the tape around to the other three stations.

They can run it essentially for free. The station in Boston may do a talk show that the other three can carry. So by getting together, the stations can provide each other with shows and can buy on a mass basis and so cut their costs. Lower costs mean more of the income is profit. So the Rectangle group makes more money than four individually owned stations in the towns. Their affiliations can be with anybody, but their hearts belong to Rectangle.

Independents

Let's take a closer look at that Washington station, though. A lot of stations around the country aren't affiliated with any net work. How do they fill up all their time? It's not easy. If, like Two Whistle, they are on the air eighteen hours a day, they don't get the thirteen-hour break a network provides. That also means they don't get the money from a network for carrying the national commercials. The programs a network affiliate gets paid to carry, the independent has to pay for. Of course the independent can charge the full rate for a commercial in any of its shows, but the full rate is probably a lot less than that of the network station. That's because fewer people are likely to be watching the independent, and you can't charge more money for a smaller crowd. So the independent faces a double bind of having to buy all of its programs and of not being able to charge advertisers as much money.

The programs the independents buy are like the programs affiliates buy-"F Troop," "I Love Lucy," and the rest. But here again the money problem comes up. The network affiliates also need to buy a certain number of shows like this, and they can afford to pay more money. So the selection left to the independent is often the really old or the really bad shows. The movies they buy may be just barely beyond the silents. The series may be one that died in 1962. And that adds to the money problem.

If the shows are that old, or that bad, the audience may not watch. That means the crowd is getting smaller, and that means the station has to charge the advertiser less and less. So there's less money to buy good shows, and so on. An independent like our Washington station, part of a group, has an advantage in that it can get in on better buys like "Bonanza" or can take videotaped shows from the other stations. But it still fights uphill on the rest of its time. That's not to say the independents invariably lose. If that were so, there would be no independents left around the country. Obviously, some of their shows do catch on, and do get big crowds. Some of them carry the hometown sports team of one sort or another. That pulls in a big audience. Some carry a good movie package and really scrimp in other areas. But the audiences for the movies justify the approach. It's just that every hour of every broadcast day has to be filled by the independent by its own hard effort. Not one of them can plug into the network, sit back, and doze till the station break.

Public television

Only one other station in town works as hard for a buck as the independent. That's the public station. They used to be called "educational," but that was not a true representation of the type of stations they were, so the title was changed. These stations, like the others, are licensed by the government but as noncommercial rather than commercial stations. Even the fighting independent can charge a sponsor for running a spot on the station, but the public stations can't raise a penny that way. They are forbidden to carry normal commercials. So they obviously can't be network affiliates either. Where, then, does the money come from? Many of these stations are connected to educational institutions of one sort or another. They are partly financed by a school board or a university. They sometimes have to carry what really are educational programs as part of their offerings, generally something like Physics I offered at 10 A.M. on school mornings. But the late afternoon and evening programs are shows as varied as " Sesame Street" and "Masterpiece Theatre." And it's usually the viewing public that comes up with the money to keep the station on the air and showing these things. If you've spent more than fifteen minutes watching a public station, you've probably caught an appeal to "send in as much as you can to help keep us on the air." That's a commercial, of course, because it is an attempt to get people to part with some money so as to have a product-the shows aired by the public station. But it's not the sort of commercial we usually think of, nor is it the sort the FCC normally thinks of, so it is allowed. So the public station is in the same situation as the commercial station. If enough people watch and like their shows, enough money will come in. That's just like the search for ratings which the commercial stations go through. Ratings, after all, are just a measure of whether or not enough people are watching. The difference comes in the range of numbers.

The public station may only need a tenth of the audience of the commercial station in order to get enough contributions. Look at it this way. One person sending in five dollars to a public station is the equivalent of a lot of people each buying a bar of soap advertised on a commercial station because the profit on that bar of soap may only be five cents, and that has to be split up with the manufacturer and the advertising agency be fore any of it gets to the station. That's not to say the public stations have as much money as the commercial stations. They don't, because there are an awful lot of people out there buying bars of soap. But the public stations do get a large chunk of support from the public, as well as from school boards and universities.

Some of the public stations, of course, aren't connected with any educational institution. In cases like that, a great deal of the time of high-level management is spent talking the big corporations into giving money as a good public relations idea.

And that usually works too. Further, if the station has some talented people around, it can start producing shows and getting the money to finance the projects from the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. This is a government agency with money given to it by Congress for exactly this use-financing program production. Other groups, like the Ford Foundation, also give large amounts of money for this sort of thing. For stations doing the programs, that money keeps people on the payroll and helps keep the station on the air.

This corporation, referred to as the CPB, is tied to another group, also paid by the government, called the Public Broad casting Service, or PBS. The programs which stations do with CPB money get broadcast by PBS over a network much like NBC or ABC. The public stations all over the country can broadcast the offerings of PBS just as CBS affiliates can broad cast the offerings of that network. So the various public stations get some help in filling all those hours just like a commercial affiliate does.

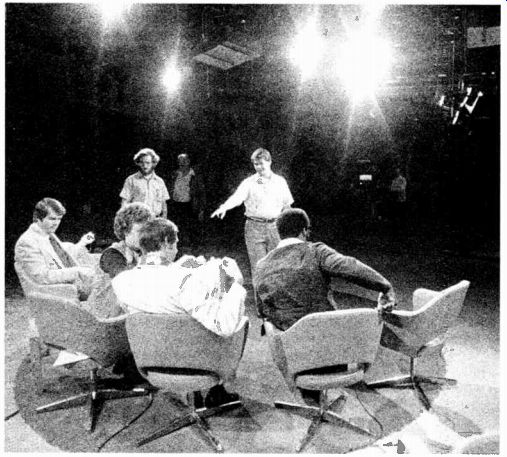

In spite of all the obvious similarities between commercial and noncommercial stations, anyone watching the two for any length of time will come away feeling they are totally different sorts of beasts. As indeed they are. Commercial stations are interested in mass audiences and so don't air shows appealing to small crowds. A dramatization of the trial of Galileo goes on the public station while the Super Bowl goes on a commercial channel. The commercial stations have money enough to produce very polished, complex productions, maybe starting in Paris and finishing in Hong Kong. The public stations may work out of two or three relatively simple sets in one studio.

The level of professionalism is generally very much the same, but the expenses are held down a lot more on public programs.

That's not to say the programs are worse. No matter how slick, the story on a commercial channel can be dull. No matter how cheap, the presentation on a public station can be fascinating.

But the reverse appeal can also happen, so it's unsafe to generalize. About as far as one can safely go is to say the public stations give more attention to smaller audiences and more specialized audiences. But what a difference that can make!

RADIO AFFILIATION

Does radio have the same sort of set-up? Not any longer. Years ago, before television, the affiliations were very similar, but there simply isn't the sort of nationwide programming for radio that once made network affiliation such a valuable thing.

Now, the closest a station gets to network affiliation is with a regular news feed throughout the day. You're probably familiar with a station that plays music all day but breaks at the hour for five minutes of news from a network like ABC. The station is more of an independent than a network affiliate because most of its programming depends on what the local owner wants to put on. The news is a service only and not an irreplaceable one the way a television network's is. Even those stations owned by the networks function pretty much as in dependents. The emphasis in radio has gone, not to affiliation, but to formats, or the style of presentation. Some stations are owned by groups, as in television, and some by networks and some by individuals, but they all approach programming in terms of format rather than in terms of variety.

So let's talk about formats rather than affiliation. For most radio stations, affiliation, when it is any concern at all, be comes more a matter of picking a source of programming. The individual station, whether owned by NBC, Westinghouse, or by John Doe, tries to build an identifiable sound on the air. Right here, let me pause to say there are still some stations concerned with offering a variety of services to their listeners.

Smaller stations and public stations tend to be the ones doing a number of different things. But it's easier to talk about the single-minded bigger stations first, and then we will consider the mixed world of other stations.

Basically, formats can be music-and-news, talk, or all news.

Obviously, you can get a great deal of variety within those groupings, more variety in music-and-news and less in all news.

Music can be Top 40 or Country & Western or Easy Listening or Classical or Golden Oldies or any number of other sorts.

Once a station has decided to go for a particular audience, the style of music is chosen which seems most likely to appeal to those particular listeners. Suppose a station decided the teens didn't have as much money to spend as a thirty-five- to fifty-year-old audience. The station's salespeople, in other words, wanted to go to potential sponsors and say "Our audience can spend more money with you than can the audience of Station WXXX." Rather than going for Top 40, this station would pick some MOR (middle-of-the-road) music. Considerations like the number of vocals as against the number of pure instrumentals, the inclusion of a big band sound, and the frequency of DJ interruptions would then come up. The station manager, the program director, possibly the production man ager, and maybe even the music librarian would sit down and talk over this sort of thing. Perhaps they would decide to have no more than one vocal for every six instrumentals. Quite likely they would decide to have the DJs on for short times only, saying as little as possible, building no particular personality a listener would identify with a particular time period. These sorts of decisions would give the station a particular sound which, hopefully, would be different from all other stations in the area. If the decisions are right, the thirty-five to fifty age group audience will indeed find that station a pleasant one to listen to. So the station will get the audience it wants. A truly careful station will even be sure the commercials it runs match its format. Suppose a national advertiser puts out a hard rock jingle for a :30 spot. That conflicts with the sound of this station, and the management may decide to turn down the account rather than run something so far out of their line. Of course, if they need the money, they may take it anyway. But the chances aren't good the audience will respond to it. So the station loses a bit of respect, and the advertiser very likely wasted his money. Just like commercials, the presentation of news will be affected by the station's style. The older audience is more interested in news than most teens. So instead of going for two minutes of news headlines on the hour, the way a Top 40 station might, this station may go for a five-minute newscast giving a bit more detail. Even five minutes every hour isn't much, so in the early evening or late afternoon, the station may go for a longer newscast, say of fifteen minutes.

Where does affiliation fit into this picture, either with this MOR station or the Top 40 one? Probably it doesn't. The MOR station is the only one likely to go for a network affiliation for news on the hour. The Top 40 will subscribe to one of the wire services, AP or UPI, and have the DJ rip off the sheet of news and read off the headlines on the air. Hence the title "rip and read" for this sort of news. Either station, though, may be owned by a group. Lotus Broadcasting may own a string of radio stations in major cities, one of which is MOR, one Top 40, and another C & W. But maybe only one is affiliated with ABC for news.

If one of their stations is all talk or all news, then affiliation is more likely, but still uncertain. If a station goes all talk, then the individual DJs build personalities which hopefully will cause people to call the station and talk over the air about various topics. Since many of these topics center around the news of the day, the station will have to have a news show of some length and regularity. Five minutes of national network news followed by five minutes of local news and weather picked up off the AP or UPI wires would not be unusual. That's ten minutes every hour. Then it's back to the listeners. For an all-news station, the wire services become essential, plus what ever other sources can be found. In some regions, a program service distributes short features, say two or three minutes about sports, every half hour. An all news station might subscribe to that service and broadcast those features. The station's staff would constantly be hard at work recording features of their own on local politics or schools or local sports teams for play during the day. But the backbone of the operation would be the wire services and their constant flow of material.

Even here, a network service might be nice, but it isn't essential.

Lots of other program sources are available.

Now what of the more varied smaller stations or public stations? Generally, some sort of music is the basic material for the station. As for all stations, music is an easy to get program source. Records are, after all, pretty commonly avail able. But instead of sticking to a particular sound all day, these stations may vary. In the morning, a public station may have nothing but classical. In the afternoon, jazz may take over for a couple hours. That may be followed with light classical till early evening. Then the station may put on a group of public affairs programs. Public affairs programs generally deal with a specific situation or a specific segment of the audience. For example, the station may do a special about the pros and cons of an upcoming vote on a bond issue. Or the station may have a weekly program with and about the Armenian segment of the population of the city. After the public affairs programs are over, the station may go back to classical music till sign off.

The small station may do much the same sort of thing, but generally far less of it. Those stations may have only two or three public affairs shows a week instead of every night. They may rely more on music throughout the day, and may fill the evening with a time for C & W or for local high school band music.

The smaller stations also don't have access to NPR, National Public Radio. This is a network providing a variety of programs for public radio stations much the way PBS does for television. NPR will provide coverage of congressional hearings which are open to the public and are of particular interest.

It will provide short segments discussing particular topics, like a review of a movie or a brief discussion of a particular artist.

It will provide a news program of some length, with reports from all over the world. It will provide live coverage of musical events from around the country. This sort of thing can do much to enrich the local programming of an NPR affiliated station.

But even so, as distinct from television, the local station still has to fill the majority of its time itself. Other sources exist: Pacifica is a group providing a non-establishment view of happenings, and many stations use their programs. But the bulk of the day still must be programmed and filled by the local people.

Affiliation is much looser and much less time-consuming for radio.

We've run the gamut from stations totally and intimately connected to a network to those not connected to anyone else at all. Affiliation, for either radio or television, can be an enormously useful and profitable condition, but it's not the only way to run a successful station. Success depends on good management decisions, and affiliation is only one of the possible decisions managers can make.

STATION REGULATION

All of us live with some rules and some laws, and broadcasting is no exception. We don't park in front of fire hydrants; broad casters don't broadcast lotteries. If we are debaters, we don't use lies to win our case; broadcasters present both sides of controversial issues. The laws may seem stronger, but the rules can be just as binding. Some, as in the case of lotteries, are laws passed by the United States Congress. Others, like the balance in controversial issues, are rules adopted by the Federal Communications Commission. And it's thiscom mission, the FCC, which regulates broadcasting because Congress has told it to do so. Their rulemaking, then, becomes just as strong as law. There is a rule-making group, though, whose rules aren't that strong but are generally followed anyway.

That's the National Association of Broadcasters, a group organized by the broadcasters themselves to set up standards and policies for all stations to follow. Not all stations follow their rules, but not doing so is like picking the flowers planted in public parks-some people do, but the rest of us think that's a cheap, petty thing to do. Likewise, the stations that break the NAB rules are generally the cheaper, less respectable stations.

So there are three sources of law-and-rule makers which broad casters deal with, and these three sources cover a wide variety of situations. Let's start with the laws.

We are all subject to a lot of laws, but only a few ever really have much impact on us. We know it's illegal to rob a bank, but we are more concerned with the law that says you get a parking ticket when your meter runs out. The broadcasters are in the same position. Primarily, they are involved with only a few major laws. One is the lottery law I mentioned before.

Congress has said it's illegal to broadcast a lottery, and it has defined a lottery as a game involving "prize, chance, and consideration." In other words, if you can win something, if you are chosen by luck instead of by skill, and if you had to pay something to get into the game, that's a lottery. If the game involved "the best essay" or "the most beautiful picture," that's something done with skill so it's not a lottery. If you can enter the game completely free, it's not a lottery. That's why so many contests say to send in a label or the company name printed on a piece of paper. You have to buy a label, but not the printing you do, so it's possible to get in for free. The game would be a lottery if you could only enter by buying a label. Think of all the contests broadcasters run--TV Bingo, bowling pals, guess the beans in a jar, guess the first day it hits freezing, and on and on. None of these depends on buying anything, except maybe a stamp to send in your name, and that's not considered as important. Generally, skill isn't a factor either, but only one of the three items-prize, chance, and consideration--needs be missing and suddenly the game isn't a lottery. Broadcasters stay out of lotteries successfully because that's so easy to do.

A harder area to handle, and hence a harder area to avoid trouble, is one generally not so trivial as lotteries. That's libel and slander. These areas are generally controlled by state laws rather than by laws of Congress. And these areas deal with the damage you do a person by virtue of what you say or write about that person. If you injure a reputation or make a laughingstock of, or cause people to stay away from the business of a person by virtue of what you say or write, then you have caused injury just as much as if you hit the person with a club.

And s/he can take you to court and make you pay for the damage you have done. Suppose, for example, you have an afternoon phone-in talk show on your radio station. And sup pose your DJ, in talking about the problems of air pollution caused by the car traffic, mentions a bad deal s/he got from a local car dealer and goes on to say s/he thinks the dealer is dishonest. Listeners might decide not to go there in search of a new car. That person's business has been hurt. The dealer's livelihood is reduced by the comments made on the air, and s/he can sue for damages. But what if s/he is dishonest and did cheat your DJ? In some states, that doesn't matter. The business has still been damaged and s/he can still collect money from you. In these states, the phrase "truth is no defense" explains the situation. In other states, however, if you can prove s/he is dishonest, then s/he has no chance of getting anything from you. Truth is a defense for you in those states.

In this example we have been dealing with slander. That's comments spoken about a person. If the comments had been written in a script, even though that writing was only read out loud by an announcer, that's considered libel. The general legal distinction is that slander is spoken and libel is printed, or written down. That distinction has a great meaning for stations, because the money awarded by courts is generally a great deal less in slander cases than in libel cases. Most stations are concerned about libel because most of what they put on the air comes from a script. But what is the situation for news? Suppose you discover a dishonest member of the state government who has been taking bribes. If you broadcast that, can s/he sue you for libel? If you're in a state where truth is a defense, and if you are absolutely sure your facts are right, you can go ahead and broadcast it. In other states, again be sure your facts are right, and then still broadcast it.

You may get sued, but the chances are small if you have the facts. The person won't want the facts to come out in a court of law proving s/he has been taking bribes. Sometimes you have to go ahead even if you're pretty certain you'll end up in court. That's expensive and a time hassle, but if the story is big enough, it's worth it.

What if, back at the talk show, one of the callers says something slanderous over your air? Can the station be sued? First of all, the station probably is running the calls on a seven or ten-second delay and so would cut any such comments. But suppose the equipment malfunctions some day and you have no choice but to go on live and some bad comments get on the air. The station is not responsible for ad lib comments it had no reason to suppose would be made and against which it took all reasonable precautions. Suppose the topic of the day is funding for a new high school. And suppose the caller starts making obscene comments about the head of the school committee. Obscenity on the air is against federal law, but you had no reason to suppose the head of the school committee would get pulled into the topic. The station is not legally liable.

Of course, you would want to cut the person off as soon as the comment started and you could tell what was happening, but at least you know you won't face law suits.

Both obscenity and profanity can get you into trouble, but not always so. The situation determines a great deal of what will happen. Profanity on a late night talk show is far different from the same word, or words, in the afternoon kiddies' shows.

Some swear words, if used appropriately, now show up in prime time. Obscenity, which is generally anything connected with sex, is still a problem. Most broadcasters stay far away from obscene words, although some underground or progressive radio stations have broadcast words which would close down an MOR station. The standards change constantly, so good judgment exercised in the particular situation is really the only guide.

Another area of law that broadcasters deal with quite often is that of political campaigns and candidates. Basically, the law says everyone has to be treated equally, but some of the applications get a little sticky. Here's the basic idea. A station must provide access to its air for candidates for federal office.

And it must provide the same sort of treatment to all candidates.

That is, one can't get five minutes on Sunday morning while another gets a half hour on Wednesday night. All the candidates for senator are entitled to equal treatment. So are all candidates for President. And for representative. But that doesn't mean that a station giving a half hour to a candidate for President has to give a half hour to a candidate for senator. Fifteen minutes may be enough, but all candidates for senator must then get fifteen minutes. The equality has to come within any one race, not within the campaign as a whole. Now for candidates for offices less than federal, like governor or sheriff, the station doesn't have to provide any time at all. The station can use its own good judgment about what races are really important and offer time only to those few. If the race for sheriff seems unimportant, then the station can legitimately decide not to have any of the candidates for sheriff on the air. But if even one is allowed on, all the rest have to get an equal chance.

Do the candidates have to buy this time, or do they get it for free? That's up to the station. It can give time to candidates if it chooses, but if it gives time to one candidate for governor, all candidates for governor are entitled to equal amounts of free time. The station, though, can go on selling time to all other candidates for other offices. Further, if the station gives time to one candidate, the station has to contact the other candidates for that office and tell them about the free time.

It doesn't have to say anything about selling time though. The assumption is that giving time away is so unusual that people won't expect it and will need to be told. Otherwise they would probably never think to ask for it.

There are some laws about the sale of time too. You have to sell to a candidate at the "lowest unit charge." That means that if you give a 20 percent discount for buying 300 spots or more, a candidate can come in, buy one spot, and get that 20 percent discount. The candidate is entitled, by law, to the lowest price you charge anyone for a spot in the particular time category. If your lowest-priced spot is at 4:00 A.M., that doesn't mean the candidate can use that rate for your most expensive time period, like drive time in radio or mid-evening in television. S/he has to use the rates for that time period, but at least s/he gets the lowest one for such times.

Suppose a candidate for governor buys time from you, comes in with a script a couple days beforehand, and has writ ten some libelous comments about the opponents. What can you do? Can you be sued, since you have the time to change things? All you can do is try to talk the candidate out of making the statements, because the law forbids you to censor remarks.

S/he can say anything s/he chooses, libelous or obscene or whatever. You cannot even demand to see a script, if s/he doesn't want to show it to you. But you can't be sued either.

The courts have ruled that you have no control over the events and so can't be held at fault. Ethnic slurs have been made by candidates in some parts of the country, but the stations are powerless to stop them. Some candidates have gotten into really dirty mudslinging, but the stations can only stand aside and suggest they start acting like ladies and gentlemen. The audience may resent what's going on and may blame the station, but there's nothing the station can do to stop it. A disclaimer saying "The opinions expressed may not represent the opinions of the station . . ." is about as far as a station can go.

But having candidates in the studio giving a speech isn't the only way they use your air time. How about the news? During a campaign, some candidate or another is always doing some thing newsworthy and thus being reported on. Do you have to give equal time for all those appearances? No, news has been specifically excluded. So long as the candidate is part of a legitimate news event, you don't have to worry about equal time. But if you include a speech in a newscast that's just a pitch to vote for a particular candidate, or just a "see-what-a- nice-guy-1-am" type of thing, then the opponents are entitled to equal time. The news exclusion also applies to any documentaries you might do, so long as the documentary is not intended to promote one particular candidate. But what about coverage of the blatantly political acceptance speeches at a political convention? Those too have been ruled as legitimate news events, so there's no problem with equal time.

There are other problems though. Suppose your weather caster becomes a candidate for mayor. Are all the other candidates for mayor entitled to as much time per day as s/he gets for the weather reports? Yes. And no station can do that, so the weathercaster ends up off the air. Suppose a candidate uses some free time to talk about things other than the campaign. Are the opponents still entitled to an equal amount of free time? Yes, because it doesn't matter what s/he talks about, it's still a use of the station's air. Suppose a spokesperson talks about a candidate. Do the other candidates get equal time? No, the law just speaks of candidates, not spokespeople. If a candidate buys spots for the campaign through an ad agency, but other candidates buy from you directly, do you have to give them the additional 15 percent discount you give ad agencies for placing spots? Yes, because the law talks of the lowest unit charge you get, not some outside firm, and that would thus have to include the agency discount.

So you can see that problems keep coming up in this area.

The intent is to give everyone a fair deal and the lowest possible price, and as long as a station tries to do that, mistakes made probably won't cause the station any serious problems.

But it pays to read and reread and reread Section 315 of the Communications Act to try to absorb all the details of political broadcasting and campaign coverage.

What of some of those rules now, as opposed to laws? An example is editorializing. Years ago the FCC said stations should not editorialize. With the passage of years and a change in members of the commission, a new ruling came down saying the stations could editorialize if they wanted to. Had this sort of thing been a law, it would have been a great deal more difficult to change from one position to the other. But now stations are encouraged to take stands. There are, however, some limits. For example, if a station says it opposes some question coming to a vote on an upcoming election, it has to offer an equal opportunity to be heard on free air time to the group or people supporting the question. That's the Fairness Doctrine. It's the same idea as Section 315 on political candidates, but this is only a ruling by the commission, not part of the law. That's not to say the ruling is any weaker in effect than the law; stations can lose their licenses for not following the Fairness Doctrine, and that's certainly as powerful a threat as many embodied in law. Because this doctrine is powerful, many people have worried about just how to apply it and whether they were, by mistake, violating its principles. Let me give you an example. Many radio stations carry a church service every Sunday morning. An atheist group has held that, under the Fairness Doctrine, they are entitled to an equal amount of time each week to present their point of view. The courts have so far ruled against them on the basis that religion is not a controversial issue. You see, the doctrine is written to apply only to controversial issues, ones about which the public holds strong, active, and varying opinions. Since no one seems too concerned about whether or not we are religious, the courts have said religion is not a controversial issue.

But what about something like air pollution? Some gasoline manufacturers have run commercials saying their product produces fewer contaminants in the air. Some ecology groups say they are misleading the public because even fewer is too many. So the groups have asked for time for "counter-commercials." By and large, the courts have held they don't have the right to such time as "puffery" in advertising is legitimate, and some overstating of a product's virtues is an acceptable advertising attribute. Further, the Federal Trade Commission is charged with handling any outright cases of fraud, so the Fairness Doctrine just doesn't apply in most cases like this. But because different courts can rule in different ways, broadcasters are not so sure of their ground as they once were.

Another area of rules which broadcasters are very much concerned about is ascertainment. As you know, all broad casters have a license from the government that lets them use a particular frequency for a period of time. But at the end of that time, the license needs to be renewed. The broadcaster has first crack at getting the license again, but s/he has to prove s/he has served the "public interest, convenience, or necessity." S/he must have been operating like a good guy or the license can be taken away. Then too, if a group in the area challenges the broadcaster's statements and says they could do a better job with the license, the FCC may decide to hold hearings to see if the challenge is correct. Sometimes it is, and the license is then given to the challenging group. In such a hearing, the FCC is interested in what sort of service the broad caster has been providing. That's where ascertainment comes in. The commission has laid down some rules on how to check up to see if you really have been serving your community. You "ascertain" the needs of your area and then see if you've met those needs. So when you apply for a license renewal, whether or not there is a challenge, you include the results of this "ascertainment" survey and a statement, generally lengthy, of how you have met the needs you found and how you will continue to meet those needs.

Some of the rules on ascertainment are fairly specific. You must continually survey your area throughout the period of your license to find what the needs are and whether or not they are changing. You have to use management-level people from your station to talk to the leaders of the various groups (like the leader of an ecology group, as well as the mayor) to get their ideas on the major problems facing the community.

You can, though, use a professional survey-taking company to find out what people at large consider to be problems. You have to make a special effort to survey those groups which are seldom organized, like the poor, or some minorities. Thecom mission has said you can list up to ten major problems you uncover, so everyone scurries around to find ten, even it it's a small community and there just aren't that many problems.

But the commission doesn't get specific at all on what you do to meet the problems. That, they feel, is a programming decision best left up to each station, so they just ask to be told what you decide to do. They don't, further, expect stations to solve problems. Some will quite clearly be beyond the scope of a station to handle. But the commission expects a station to do whatever it can to contribute toward a solution, even if that's only getting everyone together to talk over the problem.

The next group of guidelines broadcasters look to have even less force than anything we have talked about so far. These are the NAB Codes, the rules set up by the National Association of Broadcasters and followed on a voluntary basis by most broadcasters. Here's an example of their approach. Broad casters should "Observe the proprieties and customs of civilized society; Respect the rights and sensitivities of all people; Honor the sanctity of marriage and the home; Protect and up hold the dignity and brotherhood of all mankind,"* and so on. I think Mom's apple pie is in there somewhere on down the list.

Nonetheless, the codes (one for television and one for radio) outline some serious attitudes for broadcasters. For example, in talking of news coverage, the codes say that morbid, sensational, or alarming details which are not essential should be avoided. That might seem obvious, but some stations have built large audiences on ambulance chasing and films of car wrecks and interviews with victims. The language of the codes may seem trite and self-serving, but that's a problem of the words, not the ideas behind them. If a broadcaster takes the ideas on news coverage seriously, s/he will indeed have a better, more responsible newscast and won't be including the unnecessary, sensationalistic details. Sometimes the ideas break through the language, and some specifics emerge that directly affect what you see or hear. The best example, I suppose, is the time limits on commercials. Each code specifies how much time can be spent on "non-program" material, that is, commercials, billboards, promos, credits, and the like. For radio, eighteen minutes an hour is it. For television, it is nine and one half minutes an hour in prime time and sixteen minutes in non-prime time. For children's shows, other limits apply along with specific ways products cannot be pitched. For example, the host of a show can't be used as the pitchman. These sorts of things definitely influence what you see or hear. Have you ever run across an ad for hard liquor on the air? Beer and wine are OK, but the code says no for hard liquor. That's not to say you won't see or hear things the codes oppose. Stations may or may not follow what's recommended, and if they don't, the NAB really has very little it can do. The association is voluntary, after all, so code-breakers can't really be penalized.

But broadcasters, just like all of us, depend at least to some extent on the good opinion of their peers. The stations that break the codes lose some of the respect of those around them, and that's generally enough to keep most stations on the side of the angels, with an unbroken code. Besides, by following the codes, stations prove they can regulate themselves, and Congress and the FCC feel less need to make up more laws or rules.

* Courtesy the National Association of Broadcasters.

The law, the rules, and the guidelines are part of a station as surely as the people behind the desks, microphones, and monitors. They provide part of the framework that contains the immense variety of stations around the country.