The machines and devices and gadgets of broadcasting aren't confined to the radio and television stations we have been talking about. For an obvious example, records and turntables and amplifiers turn up in houses as well as in radio stations.

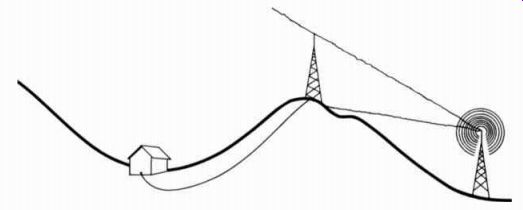

There are other uses for the electronic toys of broadcasting, sometimes for the entertainment of a few people and some times for another business use. When they are used for business purposes other than broadcasting, they sometimes are involved in what has been called "narrow-casting." CATV Cable television is an example of this narrow-casting. Instead of sending out a signal over a broad area, cable operations restrict their coverage to places joined together by a cable much like a phone line. The original purpose of this was to get television signals into areas where they otherwise wouldn't reach. The idea sprang up in West Virginia, a very hilly state, because towns down in the valleys were blocked by the hills from receiving the straight-line television signals. So someone thought of putting an antenna up on the hilltop, capturing the signal and sending it over cables down to the houses in the valley.

FIG. 1 Signals blocked

FIG. 2 Cable hook-up

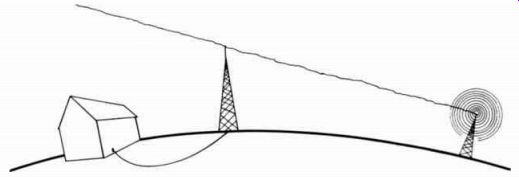

FIG. 3 Cable for distant signals

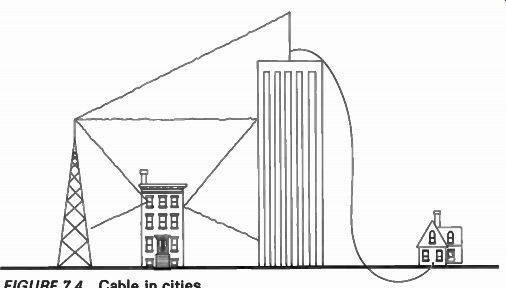

FIG. 4 Cable in cities

Thus was born the community antenna television (CATV) system. From that, the idea spread to little towns just beyond the reach of big cities. The television stations of the little towns were generally not as varied nor as professional looking as the big city stations. So someone thought of putting up a very high antenna to pick up the signals going over the town and sending them, again by cable, to the houses of the area.

Finally, in the big cities themselves, many people found their reception wasn't very good because the big buildings around them either blocked out the signal or bounced it around so much that all you could see was a picture with fifteen ghosts. An antenna on top of one of the tall buildings would get a clear signal which could then be sent to the houses for clear, watchable reception.

In all these examples, someone got paid money for providing the antenna, the machinery to amplify the signal, and the cables to distribute it. Each house paid a fee for the clear signal. Operators of cable systems began to see chances of big profits. After all, they could provide dozens and dozens of channels, most of which would be available for use other than just relaying network television shows. One channel could give time and weather information, another could be used for movies run by the cable operator and sponsored by local merchants.

People even began talking of using the cable connection in a two-way fashion, so a person could sit at home, turn to a channel for a particular store, select merchandise, and punch a button to indicate to the store that s/he would like to buy what was then on the screen. Some people talked of wiring a whole city together and using the cable system as a way for people to cast their votes from home. Cable operators started talking of covering the local sports events at the high school and the town council meetings. Ideas on uses flew thick and fast, and all within the reach of current technology.

So why didn't it all happen? Complaints started to be heard, first from the local stations in those little towns which now had big city stations brought into their area. They felt they would end up losing their sponsors and hence their profits and hence their ability to run at all. Here's why. Suppose a small town has an NBC affiliate as one of its local stations. The little station doesn't make as much money as a big station, so it tends to preempt some programs during the week a bit more often than the big city stations which make plenty of money running a full NBC schedule. Then too, the production on the smaller station is usually a bit sloppier. They are a bit late getting back to the net shows, so a bit of the beginnings get clipped. Also, the shows run in those preempted times and in early fringe when NBC doesn't provide anything are not as new or as good as the ones run from the city. The little station can't afford to buy as good shows. So with all these factors, the owners of the little station figure that if the big city NBC station is available in their market, people will watch it instead of the local station. Then the advertisers in the local area won't be as interested in running spots on the local station, because the audience isn't there any more. So they will switch to news papers or radio or billboards or whatever. So the little station can afford to pay even less for syndicated shows for those preempted spots, and even less for people to run the station breaks. For less money, the people are less competent generally, and the breaks get even sloppier and more clipping happens. So a cycle is set up that really hurts the local station.

The networks, too, weren't too happy about the situation because they could see their number of affiliates decreasing if little local stations started folding. Sure, their audience size might stay up, and they could sell as much to an advertiser, but they would face a couple problems. NBC has at least a little leverage with that small, local station. The net is the major source of programming and can thus insist, successfully, that affiliates do some things for the net. Wholesale, constant preemptions just don't happen, for example, because the net does not want that. But with a cable system, picking material up from dozens of sources, the threat of losing material from any one doesn't amount to much of a threat at all. So a cable opera tor might end up preempting NBC shows whenever s/he wanted for the sake of profit, but much to the detriment of the network. Also, the little station is bound by contract to take commercials the network runs. But what is to stop a cable operator from running the shows, but covering every commercial on net with one by a local advertiser? The cable operator could offer prime time spots for a very low price to local people, and NBC could do nothing. National sponsors wouldn't get the coverage they paid NBC for, and so would demand lower rates. That, of course, was something NBC didn't want to consider.

Further, there were a lot of people who felt that taking shows off the air the way cable does and rebroadcasting them is much like stealing the material from a copyrighted book.

It's living off the author's brains for free, and that's not fair.

Likewise, stealing a show isn't fair. A producer of a show gets paid by the network for the use of the show. If cable uses the show, producers felt they should get paid by cable operators.

Cable operators answered this way. The little station might face stiff competition from a cable operation, but all our businesses are based on competition, and if they can't measure up, then they ought to go out of business. As for the networks and producers, they had provided their material for free to the public for years, and could not now say the material had to be paid for. The shows are quite literally in the air for anyone to grab, a system the networks had agreed to and supported for years. They therefore had no say in what happened when the signals did get grabbed.

The networks and the stations appealed to the FCC, as that agency sets up rules for their operation and hence seemed the logical place to go for help. But the cable people maintained that the law said the FCC could handle broadcast matter which went out over the people's airwaves. It could not control material which is put on privately owned cables. The FCC said that since cable operations were dependent on material under the control of the FCC, the use of that material could be controlled to a limited degree by the rules of the commission. Courts agreed, so cable operations came under some control of the commission, although not totally. For example, one ruling said that small stations could demand that cable operations within their coverage area rebroadcast their programs instead of the duplicates from big cities. That still left the cable operations free to broadcast the shows which the little stations preempt, but for the majority of the time, the little station and its commercials were protected.

This single rule also stopped a lot of the worry about cable operators playing around with commercial time.

Here's why. Suppose a cable operation has a thousand houses wired in. The cable owner can offer a sponsor a spot within a network show for $1000, or a dollar a house. But the local station, now carried by the cable operation, reaches those thousand houses, plus all the others that get the signal off the air. The station can offer a spot at the station break, almost as good as within the show, for the same $1000 but guarantee reaching, say, 20,000 houses. That's a nickel a house. That's such a better deal that cable now can't compete. So it's no longer worth their while to maintain the staff necessary to cut in and out of network shows. The problem vanished.

The problem of stealing material was never resolved be cause the courts seemed to feel that both the networks and the producers were, after all, making money on their efforts, and to try to right the wrong might break up the whole system of over-the-air broadcasting. In other words, the damage being done was not so great as the damage that might be done in trying to fix things.

The FCC went further and said cable operations with a certain number of subscribers had to start originating their own programming. If they were to be connected with a system in tended to serve the public, as broadcasting is, then they would have to provide service by originating programs. That's where the town council meetings and high school football games come in. In most instances, though, the ruling became a moot point because the cable systems simply didn't grow very large.

People were unwilling to spend five or ten or fifteen dollars a month to get clear pictures when for free they could watch a picture generally only a little bit less clear. Cable became a big operation only in those areas where almost no one got a decent picture. And without a large number of subscribers, the other possibilities of two-way communication and voting at home and so on simply became too expensive to start. The potential of cable remains as large, but the actual development has slowed a great deal. People are unwilling to pay for what they can get for free. Until cable offers a product which can't be had for free elsewhere, that development will stay slow.

INDUSTRIAL AND EDUCATIONAL

There's another form of wired-in television that uses the machines and techniques of broadcasting and is familiar to us all.

That's the closed-circuit systems of stores or schools or big companies. Stores use it for a check against shoplifters and other thieves. Schools use the closed-circuit system for teaching purposes. Big companies use it to train employees or to exchange information among widely separated branch offices.

All three consider videotape recording to be an essential partner to the cameras themselves.

Stores, and this includes banks, probably have the simplest systems. They simply mount cameras, small viewfinderless ones, in high spots which overlook areas of the store. Then the signals are fed to some central room where the scenes are often continuously recorded on tape. That way, if anything hap pens, the store has a picture of it for identification purposes.

Of course, a security guard watching the monitors can spot any shady activity and call people on the floor and tell them where to go to check out the suspicious person. That's a simple system, but a useful one.

Schools and companies get into more complex situations.

They are interested in presenting a complete unit, or show.

The show may be one lesson in a series on botany, or it may be an explanation of a new product which the company's salespeople will have to explain and sell to others. In either case, the show will most likely end up looking like what we watch at night. A title, a music theme, maybe an announcer, and an opening cover shot generally start the presentation.

Then it's covers, close-ups, cuts to illustrations, and so on.

The ending of the show may even have credits! The uses for the shows are different, very definitely narrow-casting, but the techniques are those of the more familiar broadcasting.

And the use of videotape becomes a great deal more important here.

The point of putting a school lesson on television is to enable the instructor to use a great many more materials than would be possible for every class. Films, slides, graphics, and so on get incorporated in the presentation. Likewise, for the company the point is to better illustrate what's important. That may include having the inventor in as a guest, using an animated film, or actually taking the product apart so as to see how it works. For both groups, repeating the same thing over and over for different classes or different groups of salespeople is ridiculous. Videotape one good presentation, and you can play it back for numerous groups and occasions.

That's where some of the variations of equipment come in.

The show may be put on a reel of tape, just like at a station.

Or it may be put on a cassette. The more narrow widths of tape, like one-half inch, lend themselves particularly well to being fitted into a cassette. That gives you a convenient package to mail or carry around or otherwise distribute. And playback machines for smaller sizes of tape can be smaller, and hence more portable. Some quality is lost in going to smaller sizes and lighter equipment, but for non-broadcasting purposes, the loss is unimportant.

HOME, AND THE DAY AFTER TOMORROW

Once you start talking about smaller and lighter equipment, you start getting close to an area of further use of broadcast equipment, and that's home use. No one in his right mind is going to buy a two-inch Ampex tape recorder for the living room. It would leave all of about two square feet to get around in. But once the machines start getting down to portable sizes, they start being reasonable additions for the home. That sort of thing has long since happened with audio equipment. Records, tape decks, turntables, cassette machines, and amplifiers are commonplace. The most recent addition on that list, cassettes, illustrates the point of what happens as things get smaller and lighter. Originally, no one thought you could get more than one track on a one-quarter inch piece of audio tape. Now we have eight tracks and cassette players that are very accurate, very sophisticated pieces of machinery in small, light boxes. When the equipment was big and bulky and the tape with one track took up a lot of space, not many people at home bothered with tape recordings. But eight-track cassettes, lighter and smaller than the original gear, are no surprise in anyone's den or living room.

As television gear gets smaller and lighter, and as variations like video discs become more easily produced, more people will start adding video gear to the audio gear they already have.

At first, the quality will be below what's broadcast, but as technology improves, the quality will come up. I think we can make a reasonable guess about what will develop for home use.

The trend in technology is to miniaturization. Tape playback units and the sets themselves will end up with very small sections devoted to the electronics. By far the biggest part will be the screen. Television broadcasting right now is locked in to a 525 line standard for the picture. A clearer picture can be had at 625 or 819 or 1003 or whatever. For prerecorded shows for home playback on a giant screen that's six feet high and fifteen feet wide, a line standard of several thousand should be reasonable. Now imagine a disc, much like a 33 record, that slips into a box. On the disc, recorded probably with the use of laser technology, is a two-hour play. No interruptions, no commercials. The price of the disc to you is comparable to a three or four disc set of phonograph records. And the picture you get is superbly clear, full color of course, and in full stereo sound.

That should be possible by the mid 1980s. A fully three-dimensional projection out into your living room should be possible by the turn of the century. It will be so completely three dimensional that you will be able to walk around the actors and see them from all sides.

What will this do to the network shows we now enjoy? Will individual stations be much competition for this sort of thing? Look at what's happened with radio. Record sales haven't hurt radio. You still get greater variety off the air than you can get from the comparatively few records you own. As a matter of fact, the records you buy are often ones you hear first on the radio. So too, television will go on providing the tremendous variety of shows it now gives. Some of the things seen on television stations may be available on discs, although I would expect most material on disc to be done for disc alone. A collection of discs of plays or operas or Broadway musicals, while interesting, would not be as fresh and new as the offerings of the familiar networks. Then one could expect the television net works to figure out a way to broadcast to those large, multiline, clear-image screens. It would be rather a television counter part to FM broadcasting. So the big screens could be used for both the free stuff broadcast over the air and for the discs you buy. And suddenly we have another broadcast form to consider.

But that's a topic for another day.

-0-