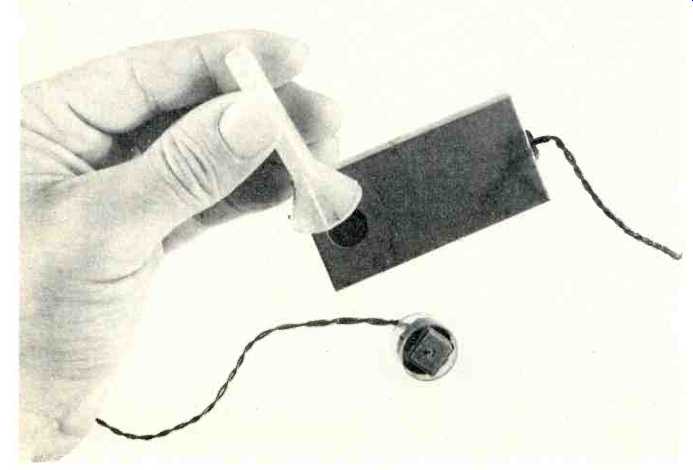

-----These two clandestine mics were dug out of a wall a few years

ago. Note that they require only a small opening into the room.

DURING THE LAST few years there has been much said, written, and done concerning electronics for surveillance. Most common are the electronic bugging methods, but following close behind are methods for voice identification, computer data storage, and "psychological" testing. Since the Watergate disclosures, all have been dealt with in sensationalistic terms, both as to their effectiveness and protection from them.

The most familiar is "electronic bugging," which takes several forms: The wired-in tap on a telephone line; a mic placed in an area of conversation; and the use of mics to pick up conversations from a distance. With all of these, there is much misunderstanding, often promoted by groups who do the tapping and by persons who profit from allegedly "de-bugging" a premises.

Telephone Taps

The simplest way to tap a telephone is to attach another telephone to the same line. This is rarely done, because simple methods can be used to detect the instrument, as each set added draws power. However, a more effective method of tapping a phone line-"bridging"-can be undetectable, since its effect on the line can be less than ordinary day-to-day changes due to electrical variations and temperature. The only way to detect a tap wired directly to the clandestine receiver is to find it-physically. If the tapping has been done on the premises, one must carry out a painstaking search for any wiring not part of the regular equipment. There are no instruments which can be attached to a phone set to detect such a tap and no such instrument will be physically possible with any contemplated technology.

Sometimes a phone will be tapped with the wires leading to a hidden transmitter. In such a case the tapper has been unable to run wire all the way from the phone to his receiver and therefore uses a radio transmission link. Such a tap can be detected, as will be discussed later.

The difficulty of detection of wired in taps on phones also exists with wired-in bugs. If the wires from a mic placed on the premises run all the way to the receiver, the bug cannot be detected by any method except a painstaking physical search. This search must be carried out in a systematic manner, by looking for unidentified wiring; looking for fresh plaster, or other evidence of recent changes in construction details on the premises; using metal-detectors to find wiring buried in walls, under rugs, etc., and checking adjacent premises to find microphones on adjoining walls. This search must be carried out square foot by square foot on floors, walls, and ceilings. In older buildings, there is often unused telephone and low voltage wiring which must be examined to determine if it is being used to carry information from a hidden mic. Telephone wiring boxes, electrical wiring boxes, and fixtures must all be opened and examined.

If any unidentifiable suspect wiring is found, a properly designed high gain amplifier driving a loudspeaker should be connected to it so that feedback to a hidden microphone will cause howl from the loudspeaker.

It is wise to use a radio-frequency detector on the amplifier when doing this in case the microphone is equipped with an r.f. converter to help elude detection. Moreover, this detector must be capable of detecting all forms of r.f. modulation-AM, FM, suppressed carrier, etc. Remember that this type of bug cannot be detected with any type of non-contact scanning instrument, unless that instrument is one equipped to pick up the very small electro-magnetic fields that could be produced by the wires. Such instruments, besides being expensive, must be used in extremely close proximity to the wires in question, and so are not usually practical for detection.

The power line itself must also be checked with the high-gain amplifier, since r.f. signals can be sent out on it.

Bug Transmitters

The most publicized type of "bug" (although perhaps one least used by Watergate-implicated agencies) is the hidden transmitter. It is this type of bug and only this type of bug for which the highly publicized detective agencies attempt to sweep a room "clean." Such transmitters obtain their power in various ways. Some are operated on batteries and therefore, have a limited transmitting life. Others are connected to a source of power such as a telephone line or the house current power line.

-----------Detection of clandestine transmitters requires costly test equipment

including spectrum analyzers, such as this one from Hewlett-Packard

Some of those that operate on house current may also utilize the power lines to send out signals; they must be regarded as wired-in. But those which have to transmit through the air by means of an antenna can be detected by tuning to their transmissions. Nevertheless, the task is not simple, for these bugs may be set to transmit anywhere from 10,000 Hz to 2 GHz with a transmission band as little as 3 kHz wide. There is space in the radio spectrum for six hundred thousand such transmitters to transmit at the same time. Of course, much of this space is taken up with other kinds of transmission such as broadcast and communications and cannot be used. However, it is not difficult to find a little space in the radio frequency spectrum to fit in a short range transmission without serious interference.

Therefore, it is necessary, in order to detect these transmitters, to have a receiver which can receive all frequencies from 10,000 Hz to 2 GHz. There are some instruments on the market which claim to do this without tuning. However, they simultaneously pick up high strength signals, such as broadcast and TV, which overwhelm the signal from that little transmitter. It is necessary, therefore, that the receiver be tunable.

However, since one has to sweep the walls with the receiving antenna of this receiver at the same time that one is tuning, using such a receiver would be a tedious job, to say the least. The task is alleviated by an instrument which automatically scans through all frequencies. Thus, every couple of seconds it examines every frequency of concern. Such devices can be tied in with a loudspeaker to excite the microphone, making the job semiautomatic. Such a convenient instrument might cost you over $10,000.

Even with this instrument, the task is further complicated because radio waves travel through the air differently at different frequencies. The higher the frequency, the shorter the length of its waves, and therefore, the shorter the transmitting and receiving antenna must be to pick up in the same way that a lower frequency is picked up. This is because the shorter the wavelength is compared to the antenna, the more the antenna is sensitive to the direction from which the signal originates. Consequently, as the instrument scans through frequencies, one would have to constantly change the orientation of the antenna or its size.

However, there is a method to solve this problem; one that improves the ability to separate the nearby transmitter from transmitters far from the premises. The method takes advantage of a qualitative difference in the electromagnetic field near an antenna and that far from an antenna. Each is best picked up with a different type of device. The device for the "near field" will pick up well only when held very close to a transmitter and does not have to change with frequency.

Thus, the de-bugging instrument must sweep through a wide frequency range, have a way of exciting the hidden microphone, and rely on a close-proximity type of antenna to pick up the transmission. Therefore, in order to sweep a room for such a hidden transmitter, it is necessary to systematically sweep closely along entire surfaces and areas where transmitters may be hidden, using the type of equipment described.

Debugging Hoaxes

Knowing this, one can view with enlightened suspicion anyone who claims he can debug a room. Indications of chicanery include:

1. connection of an instrument to a telephone line to see if it is clear of taps;

2. setting up a receiver in the middle of a room, turning a dial quickly to see if the room is clear of hidden transmitters (Sometimes a variation on this involves producing a single tone from a loudspeaker and listening for that tone on the receiver which is set in the middle of the room; besides the fact that many transmitters will be missed by this procedure, the single tone in the room may actually produce a dead spot where the receiver is; any attempt to excite an acoustic field in a room must use bands of noise or warbled tones to avoid such dead spots.);

3. completion of a survey and certification that a room is clean of taps and bugs after less than 10 hours survey.

Parabolic Mikes

A final type of audio surveillance involves the use of methods to pick out voices from a distance. A favorite of feature writers is the method for picking up speech from vibration of a window pane excited by the sound. The method utilizes a laser beam reflected back to a receiver which detects the modulation of the beam due to the vibration. Such vibrations are often of amplitudes less than the diameter of an atom, so great care must be used in setting up the laser and the receiver.

While the tedious task can be accomplished, a slight repositioning of the window would cancel the effort. A more likely method uses a line microphone (sometimes called a "shotgun" microphone) which is able to pick up speech with reasonable intelligibility at greater than 200-foot distances through open air. The predecessor to the line microphone was the cumbersome and less effective "parabolic" microphone which erroneously tried to use a reflector to treat sound like light. These are seldom seen now.

------------This "shotgun" mic, E-V's DL-42, can be used to pick

up conversations 200 feet through as far away as open air.

Voice Identification

During the past few years an attempt has been made by police agencies and the media to equate the reliability of spectrograph "prints" of the human voice with fingerprints. Little has been pointed out to the public concerning the probability of correct identification using this method. At present, the most carefully controlled experiments with voice identification have produced a 97 percent correct identification-compared to virtually 100 percent for fingerprints. However, even these controlled experiments (which used computers, not spectrographs) were taken when the number of choices of different voices were in the vicinity of 50. Each of these people spoke the same words and each of these people was recorded on exactly the same high quality equipment in the same acoustical environment. When any of these factors are changed-for instance, the number of people is increased to hundreds or thousands, or the transmission channel is different for each voice (such as different microphones, recorders, or telephone transmission), or the words and sentences spoken are different-the probability of correct identification turns around and becomes far less than 10 percent. Thus, for voice identification with any accuracy one must use a computer, have a small number of people involved, and they all must speak the same words into the same microphones on the same recorder. Yet, even under these ideal conditions, the best accuracy that has been achieved is about 97 percent-still indicating "reasonable doubt" in our courts.

Psychological Testing

Related to the pseudo-science of voice identification by spectrograph are the various methods of psychological testing by electronic instrumentation (called by Senator Ervin "Twentieth Century witchcraft"). The most well-known is the so-called "polygraph" or lie-detector. It is called a polygraph because it plots the changes of several human body functions with time simultaneously on a piece of graph paper, together with an indication of the time a question is asked. The operator asks a question, then interprets the effects of the question on the combination of body functions. No single function, such as pulse rate, can be used-all must be used. This is called, technically, "stress correlation." Another claimed "stress correlate" to truthfulness has surfaced in a recent commercial product now being sold to police departments. The company selling it claims that a sub-audible waive ring of the voice occurs when a person lies--and the company has a meter to measure it.

Most psychological activity in the human being is "related" to body changes which can be measured electronically. This relation is used for medical encephalographs as well as for monitoring men in space. However, the key is the "correlating," that is: what changes correspond to what activity? In the lie-detection process, the "trained operator" does the correlating (called "interpreting")--and many questions have been raised concerning his qualifications.

As a result, both government and private research funds are now being spent to use computers for such correlation. In the course of this research, it has been recognized that additional information about the habits and personality of the individual are needed to supplement the measurements being made. The computer's memory storage must be called upon.

We often allow ourselves to think that computers are unreliable; that you "put garbage in, get garbage out," and this is the fault of the hardware.

This myth is fed particularly by mistakes in consumer credit billings.

However, such error is not inherent in the computer--it is only reflective of the budget of the user of the computer. The present development of a government storage facility based on social security numbers is well-funded and far more fool-proof. It is possible to link this bank with the similarly well-funded National Crime Information Center, a Dept. of Justice data bank. Storage elements are now available which can put the vital statistics of every person in the United States on one disc about 16 inches in diameter; that is one disc 16 inches in diameter for all the people in the United States. Obviously a small room containing such memories could contain large amounts of information on large numbers of people and be readily accessible. While the access methods to information stored in such densely packed memory elements are not completely developed at this time, they are easily within a couple of years of "going on-line." The technical capability for correlating many details of information on individuals, from bugged conversations to appropriated medical records, is now becoming available to both private and government agencies.

Can One Talk in Confidence?

To protect oneself, one could start with a program for detection of hidden microphones--but it would be an expensive program. A less expensive approach would make the bugs ineffective.

Speech is very similar in its physical characteristics to random noise. When speech is mixed with an equal energy of random noise, it is nearly impossible to understand without visual cues, such as movement of the lips of the speaker. Furthermore, such a mix is impossible to decipher electronically by any methods known today (although a new computer-based technique called "linear prediction" may make it possible in the near future). If noise equal to or louder than the speech reaches a hidden microphone, the speech will be effectively "masked." The problem, then, becomes how to create this level of noise while still being able to carry on conversation.

The simple solution to this problem is to bring one's mouth close to the ear of the listener. Since this is physically inconvenient, it can be simulated by placing a noise-cancelling microphone close to the mouth of the talker and headphones on the listener. For a conference, all participants would be interconnected. Today, such multiple microphone and headphone systems are widely available for use in classroom education. With such equipment, a relatively low level of noise can be generated in the room so, with people speaking softly into the microphones, private discussions can be carried on without fear of detection. Care must be taken that at any point where a microphone may be hidden, the noise is always louder than the speech.

While this may be a relatively inexpensive way to circumvent the bug, it conjures a frightening picture of the living room or office of the future.

Excessive use of data banks will be less yielding to technical gimmickry.

Perhaps the gimmick must give way to legislation.

Beginning July 1, this year, Sweden began an official Data Inspection Board which is empowered to severely restrict programming of private data banks and to play an advisory role regarding government banks. Meanwhile, here in the U.S.A., according to Electronics, July 19, 1973, "limits are still fuzzy on what the Department of Justice and its FBI can do with arrest records and other data in the National Crime Information Center." It is easy for the investigator to perform the illegal act necessary to bug a room or tap a phone; but difficult to detect and remove is the intrusive device. It is easy to enter information in the data bank; but difficult to get it removed or corrected.

Shall it be as easy to lose our right to privacy-and as difficult to regain it?

---------------------

(adapted from Audio magazine, Jan. 1974)

Also see:

Quadraphonic Headphones (Jun. 1973)

= = = =