It is an article of faith in the world of audio that as the quality of a high-fidelity

component system improves, the reproduced sound increasingly reveals a higher

degree of fidelity to the sound of the original performance.

Unfortunately, it is equally revealing of the flaws and technical shortcomings of the various storage mediums used for playback of recorded music.

While prerecorded open-reel and cassette tapes have their devotees, the phonograph record continues to be the principal program source for music.

Whether an audio component system is very modest or the most expensive assemblage of audiophile exotica imaginable, the owners of these systems share a common complaint: They are outraged by the poor quality of a very high percentage of current phono graph records. They must cope with physical deformities of the record-pinch warp, dish warp, and combinations thereof.

Surface noise is, of course, the most irritating factor in the playback of phono graph records. Noise can be of an intermittent nature, such as ticks and pops, or of cyclic character, such as swishes and thumps. Then there is generalized steady-state noise such as hiss, crackles, graininess, and frying as well as low-frequency rumble-type noises. These can all arise in many areas of phonograph record manufacturing.

In the cutting of the master lacquer, low-frequency noise caused by rumble inherent in the cutting lathe is quite rare--but it can happen. As the cut ting stylus cuts a record groove, a "thread" of the acetate lacquer compound is displaced. This "chip," as it is called professionally, is removed from the groove by a vacuum suction tube mounted very close to the cutting stylus. The angle at which the chip is removed and the speed of its removal can have an effect on the noise level of the lacquer.

The electroplating of the lacquer is a much more complex process than is generally realized, and there are many ways in which noise can be generated during this stage. The degreasing agent used to clean the master lacquer can be a factor, and the type and quality of water and degree of filtration are also important. The type of silvering solution and its mode of application to the lacquer can affect noise, as can the amount of current and the speed of metal deposition in the initial plating, the manner in which the plated father is separated from the master lacquer, and the speed and type of plating used to grow the mother. The manner in which the backs of record stampers are ground may determine whether mold grain will be produced, which causes a low-frequency noise akin to rumble. When a lacquer is cut, the cutting stylus throws up tiny splashes of lacquer compound on each side of the record groove, much in the way a plow moves through earth. These are called horns, and the manner in which they are removed from the stamper also affects noise.

In the record pressing itself, there are many aspects which can generate noise. The vinyl record compound is singularly important, and while you see many record jackets stating the record is made from "pure virgin vinyl," there really is no such thing. In particularly gross cases, the pressing compound is a mix ture of new vinyl plus various percentages of vinyl reprocessed from old re cords--returns from dealers, over runs, etc.--which are ground up, label and all, filtered to a certain degree and reused. In some justification of the "virgin" designation, some records are pressed from all new vinyl powder, but they also contain many ingredients such as lubricants (lead stearate), stabilizers, plasticizers, and sometimes antistatic agents. It is sad to relate that al though one company has had an effective antistatic chemical for years, their patent is about to expire. The agent has never been used since it would have added a half-cent to the cost of a record! The duration of the pressing cycle can be a determining factor in both noise production and in the physical characteristics of a disc. There are other factors, too numerous to mention here, in the manufacture of phonograph records that can affect the ultimate quality of the record.

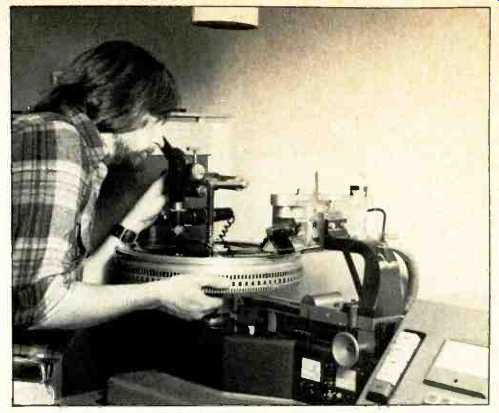

---------A technician at Sterling Sound Studios in New York checks a master

lacquer which he has cut for the Franklin Mint series.

Foreign Finds

For some years now, a number of audiophiles have bought the original foreign editions of classical recordings rather than our domestic pressings of the same recordings. For example, they would buy EMI records from England instead of pressings made by Angel Records in this country. Their reasoning was that the foreign pressings were of far better quality. This was amusing to some people, since many audiophiles abroad complained about the quality of recordings made in their country! It can be fairly stated that the recent phenomenon of audiophile quality recordings had its genesis in the general dissatisfaction with domestic record pressings. By this time, most audiophiles know that the German company Teldec manufactures the records for many of the audio specialty record labels. Telarc and Crystal Clear are two companies that use the Teldec ser vices. In general, the Teldec pressings are a considerable improvement over anything domestically available.

Nonetheless, I have found their quality to vary in certain aspects. Some recordings are really first-class: Low in overall noise, few ticks and pops, and minimal warp problems. Others exhibit crackling noises and dish warp.

Mobile Fidelity pressings are made by JVC in Japan. Using very high quality CD-4 vinyl and obviously exercising great quality control over all the processing stages, the Mobile Fidelity pressings are the most nearly perfect I have ever encountered. It is not un common to play a whole side without a single tick or pop, and steady-state noises are usually not present. Their silent surfaces are eloquent testimonials to the fact that such records can be made, albeit at a higher cost per unit.

Is there any hope that such splendid pressings can be made in this country? Perhaps more to the point, can such good pressings be made consistently? Surprisingly, the answer is yes. I'm sure most people have seen advertisements from the Franklin Mint in Pennsylvania. As well as manufacturing very high quality commemorative coins and medallions, they have been offering a wide variety of objets d'art. Commemorative or artistic porcelain plates and bird and animal figurines, and similar items are their specialty. Now they are offering classical recordings, such series as The 100 Greatest Recordings of All Time (surely an ambitious title and certainly subject to argument). Most of the music is leased from the major record companies; some of the material is on the old side, while other recordings are comparatively recent. It is how they manufacture their records which is of interest.

Master lacquers are usually cut from the master tapes by Sterling Sound in New York. The lacquers are sent to Presswell Records in Ancora, New Jersey. Presswell then does the vitally important electroplating.

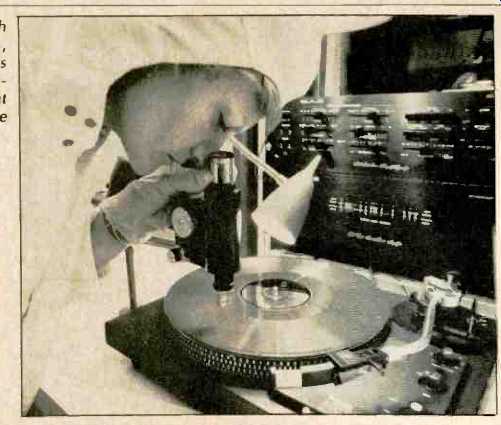

--------- In conjunction with listening tests, Presswell Records clean

room personnel check discs at regular points in the pressing run.

Pressing Matters

In the electroplating process, Presswell uses many proprietary techniques to ensure high quality. For example, the water used is both deionized and distilled with triple-state filtration capturing particles down to a size of one micron. Initial electroplating is at low current level and slow deposition speed to ensure fine-grained metal plating. A special method of burnishing the backs of stampers is used to help reduce low-frequency mold grain problems. In most record plants, dehorning the stamper is accomplished by clamping the stamper to a special turntable, and, while the stamper is revolving, applying fine-grade jeweler's rouge with a pad and a certain amount of physical pressure.

Presswell feels that no matter how carefully this is done or how thoroughly the stamper is rinsed with water, there is often residual particulate material remaining on the stamper which causes noise.

Presswell does not use this method of dehorning, and instead uses a proprietary method that does not generate noise. Curiously, Mobile Fidelity Records insists that their stampers not be dehorned. They claim that to do so attenuates high-frequency response.

Mobile Fidelity states that the first several playbacks of their records will have a certain amount of noise, but the burnishing action of the playback stylus will effectively dehorn the record so that subsequent playback will be from the quiet surfaces for which the label is noted.

At Presswell, a special clean room has been set up to press Franklin Mint records. The room is equipped with LENED automatic record presses, electronic dust precipitators, and has positive outward air pressure. All clean room personnel wear anti-dust gowns, head caps, gloves and shoe coverings.

The Franklin Mint pressing compound is a very high purity vinyl containing an antistatic agent. A special dye gives their records a distinctive opaque burgundy color, and they weigh about 150 grams each, about the same as high-quality audiophile records. The pressing cycle is of the so-called "symphonic" variety with longer heating and cooling times to minimize problems of "non-fill." This is a condition in which the record grooves are not molded properly. The LENED presses automatically remove the flash--excess vinyl squeezed out of the press by heat and pressure--and automatically stack the records on spindles. This avoids pinch warp and produces records which are quite flat. After every 50 pressings, the records are given an audio playback check. The results of all this care with Franklin Mint records are gratifying. Surfaces exhibit few ticks and pops, and steady-state noise is rarely encountered.

Equally encouraging is the record quality offered by Presswell in its regular pressing facilities. They use the same electroplating techniques and the same LENED automatic presses.

They have been pressing the records for the London/Decca Treasury Series and for such special items as Luciano Pavarottí's O Solo Mio album. These discs are pressed at 120-gram weight, still quite a bit more than the common 95- to 105-gram variety. Pressed with a modified symphonic cycle, the examples I have played were quite satisfactory. The records were reasonably flat, few ticks and pops intruded, and cyclic and steady-state noises were either minimal or inaudible. I would have to say that these Presswell records were certainly the equal of most Teldec pressings and, in some cases, superior to them.

As you can see, there are many things that can go wrong in the production of a pressing, but it is gratifying to know that the foreign manufacturers do not have a complete monopoly on the production of high-quality pressings. While they are not as common as one would like, they can be had.

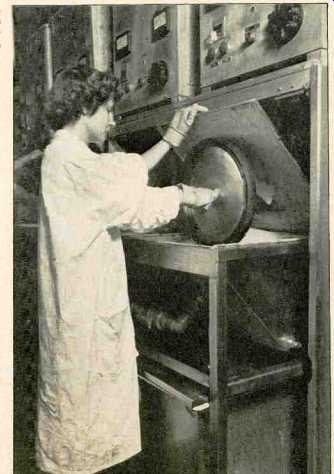

-------- The plating operation for the Franklin Mint records is at Presswell

Records in Ancora, New Jersey.

-----------

(Source: Audio magazine, Jun. 1981; Bert Whyte )

= = = =