by EDWARD TATNALL CANBY

NEEDLE TALK

Installment VI-new title: "My Lifetime in Audio & Music." On second thought, maybe the original title was better: "How I Fell into Audio." Either way, you'll find Chapter V in the May 1983 issue.

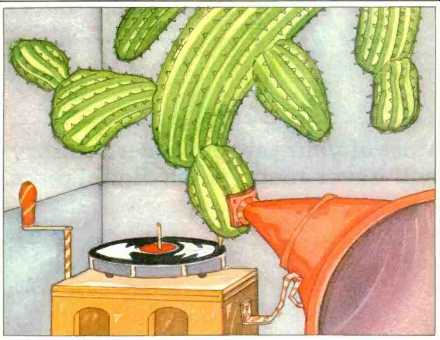

I left off on a curious note--the wooden phono stylus. Yes, it existed, and for many years. This was the stylus or needle that, in the mid '30s, was required by my university's music department for all who borrowed our 78 rpm records. They came in two types.

One was naturally grown (and naturally variable), a sharp cactus thorn. The other was a triangular cut shaft of, I think, bamboo, sliced neatly off at the diagonal by a special hand tool. The apex of the resulting triangle at the end was a sharp point--for a few minutes, until it wore down. Then you sliced it off anew and again had a sharp point for several minutes. Excellent, we thought.

Some fancier phonographs had a triangular shank expressly designed for these wooden styli, though the ordinary round needles would also fit.

I should explain for the young and unknowing that all styli were then called needles and were invariably removable. The norm was the old steel needle, out of acoustic days, also used in electric (electronic) phonographs. In the earlier acoustic machines, they came in a number of thicknesses ("loud needles" and "soft needles") for varying volume levels. These were fastened into the shank with a set screw on one side; you were supposed to use a new steel needle for each and every play (maximum four-plus minutes) but nobody ever did.

Instead, as I can testify from abundant personal observation (not to say action), we retrieved used needles from cracks and crannies on our machines if we could pry them out; or failing that, we took them from those handy little round metal boxes with the hole on top that were built into many phonographs to take used needles.

Just lift off the cap and there they were, waiting for further service. Stylus discipline, as you can see, was lax. One could call it almost fatalistic. The only time anybody I ever knew put a brand new needle to work was when it was absolutely impossible to find an older one. Since steel needles had been marketed for a long time, this seldom happened. Throw away a dangerous point like that! Better to keep it where it belonged, out of harm's way, and so we did.

The sound of a used needle? Well, fuzzy. Going on to worse. Especially at the beginning of a side and again at the vulnerable inner grooves. It was a sound not unlike the recent squalling of the "transistor" when pushed beyond capacity--the little ones, I mean.

Unpleasant, but you got used to it. In time, that distortion was transferred to the record itself and so made semi-permanent, but by then you couldn't distinguish between the bad needle and the bad record, so why bother? More fatalism, or should I call it laziness? It was indeed a distorted sonic world much of the time. But never forget it was functional and useful. We could hear the music, even if it was too much trouble to change needles.

Yes, we were lazy, if imaginative. Aren't we still? Did I hear somebody mumbling about video remote-control units at $$$? Now it's video laziness.

For many sophisticated souls in the 1930s, the muffled sound of a wooden stylus point was preferable :o the metallic screech of the normal steel point, and they were probably right. The gourmets of the phonograph used them assiduously and boasted about it. As for us at my university, the wooden stylus meant first of all safety--no-scratch, no-gouge. That's why we, and other early record-lending libraries, required their use.

Should I make a further aside to explain the needle point? Guess I'd better. There are many ways to cope with human failings, and the phono people had long since worked out an ingenious means to insure an optimum (relatively) needle point under these circumstances. Just provide a reasonably sharp end to your needle-no special radius configuration and all that jazz--and grind it down to size in the actual playing. Brilliant idea! All shellac discs, therefore, included an abrasive in the basic formulation which allowed the groove to shape the stylus unto itself, more or less. Do not be surprised, then, if your ancient shellac collectibles seem terribly worn for the first half-inch or so of play. That was the mechanical adjustment area, where groove and stylus came to mutual terms. Often, it was a battle.

Each time you put a used needle back in service that job had to be done again, with a vengeance, for it was impossible to align the usual needle in its socket; it just went in any old which way, including sidewise like a miniature bulldozer. Moreover, the grinding process worked well only so long as the cross-section of the needle tip was no wider than the groove itself. By the time a used needle had been in and out of service, on a number of occasions its point had widened with wear and there was shouldering; the needle leaned on the groove walls to each side and began to add addled echoes of preceding and approaching music to the general mishmash. Dreadful thought but only the sober truth.

I do not frankly think we do any better today, if in other areas. Have you listened lately to your neighbor's well-worn hi-fi system, bargain-style from some department store outlet? Does he even notice the hideous (to you) sound? Do not feel superior when I recount these misdeeds of the past! When I left the Great University and its record collection and moved to New York, I took up my second music appreciation job, not at a university for males but the very opposite, an ex finishing school for young ladies that had nominally become a two-year college. They wanted a music course suitably tempered to the "frivolous" female mind, upper-crust type. A touch of Culture but, please, nothing abstruse or too difficult. These ladies had more important things to think about, like clothes, money, marriage to the Right Boy.... Now I can smile indulgently, but in those days I was all set for battle and, by golly, it was going to be all-out.

Via audio, too.

This was where by some miracle I ran straight into my second Carnegie Collection, with another of those monster state-of-the-art record players. It was like a gift of planes and tanks to a struggling third-world country-me. I was armed to the teeth with music. I fought the good fight there for four whole years and, I hate to have to say, I made more progress among those lovely young socialites, percentage wise, than I have in 30 years of battling for music in the much larger world of audio buffs. (Dare you to print that, Editor!)

Which is to say, in different words, that I enjoyed it, every bit, both the music and the students, frivolous or no.

One of them, for instance, was the president's sister, a wonderfully charming Irish colleen type, even if the musical portion of her brain was the size of the proverbial pea. We despaired of ever getting her through with a passing grade, but the other girls pitched in and helped and so she made it. She had to play the monster, the big Carnegie Phonograph! All of them did, records, needles and all.

Which gets me back to those needles. At the University, earlier, we had no students playing our equipment. I ran the Carnegie machine, I was its boss, and I did change the needle, every single play, like a dedicated monk. I also lowered the heavy pickup carefully. It never squawked or scraped. Indeed I was just too perfect for words. But in New York the girls had direct access to everything and, indeed, played all their musical homework on the Carnegie machine, lacking for the most part any portables in their bedrooms. It was housed in the school library and therefore could never be played loud--the librarian saw to that.

But that was all she did. She signed out the records and they did the rest.

Mayhem! No use trying to enforce a wooden needle rule. Those girls didn't know a cactus needle from a diamond brooch, and, they would use either one if it made any noise at all. In case of need there were always safety pins, etc.

When I saw what was happening -- those sweet, innocent girls, the agents of sheer destruction!--I knew something had to be done fast. But what? We started in with steel needles and fed them directly to the girls, for free, handfuls of them. No avail! How could they tell the new ones from the old? They didn't bother. In no time at all we had piles of scimitar-like steel shards in active use on our records-sometimes there were actually broken-off points, visibly so, though how they managed that I never could tell. Like everybody, they blamed the machine.

Or the record. "Mr. Canby, that Hayden record you told us to play (i.e., Franz Josef Haydn) doesn't make any noise when I play it. And the needle sort of slides around. Do we have to know that one for the test?" Then I had a bright idea, state-of-the-art. At that time, with war still holding off here, though it was at its worst in Europe, some bright-souled innovators were selling permanent needles. You guessed it: They had sapphire points and were ground to fit correctly, for an astronomical number of plays. Wow--was that for me, for us! Just put one of those in the machine and our problems would be solved. E pluribus unum! Out of the many, one. So I bought one. It cost a fortune, the school's money, equivalent perhaps to $50 or so today, maybe more. I installed it, tightening the set screw so that it could not be released short of a pair of pliers or a wrench, and gave my instructions to the librarian. No more steel needles! The girls are not to touch the needle assembly; just play the records. And tell them to be careful-that's a sapphire point they are using. It'll play forever. No need ever to change... . And so I went away, breathing sighs of relief. That problem solved, and so simply. True, true! Haven't we all converted to millions and millions of jewel points today, and long since? It was a brilliant forerunner, that experiment of mine, forecasting much that was to come, etc., etc., etc... . When I returned a few days later, one of the girls said, "Mr. Canby, the phonograph is making a funny sort of noise--though I did play all the records you assigned for the test." (Just in case I thought she hadn't.) I went for a quick look. Yes indeed, a funny noise. For days, the girls had been playing all their records with a jagged shank of metal that once held a sapphire. The jewel had lasted maybe a side or two before being knocked out.

Nobody even noticed.

Well, this story ends gracefully. A new Swiss-made needle appeared, low in cost, called the Recoton. It used steel, not sapphire. Such ingenuity! This needle had a very hard, very thin steel point, rather, a thin steel wire shaped at the end, which was imbedded in a fatter upper metal shaft that went into the usual phono pickup.

Sounds unlikely, but these needles played well and for much longer than the usual steel sort. With wear, they were thin enough to avoid most of the shouldering problem--no fat cone.

You could play dozens of sides with them. If you were careful.

But their real virtue you will not imagine. Very hard steel is brittle! Under stress, these needles broke right off, cleanly, at their wasp waist. So neatly, so deliberately calculated, that what was left, the thick upper part, would not play at all but just skittered harmlessly over the surface. You had to put in a new needle. Moreover, if you dropped your heavy pickup, the point also broke, leaving just a small nick instead of a deep gouge, and the same for sidewise scrapes. Devilishly clever, obviously intentional.

So we converted to Recotons, and our problem was really solved. We used zillions but no damaged points ever got back into service-they broke first. Purposely delicate. I loved the idea and blessed Recoton once a minute for four whole years thereafter.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Jan. 1984; EDWARD TATNALL CANBY)

= = = =