One of the strangest conventions in this country of ours is the Convention,

that biggest of annual get-togethers. The Audio Engineering Society calls theirs "Technical

Meeting and Professional Exhibits," but like many others it is a monumental

festivity which provides, for a few brief days, the total emphasis we need

on our own special world-within-a-world, brought to its ultimate splendo-r-isolated,

insulated, outshining all else like some supernova in a galaxy. The Convention

is big-as big as we can make it. Also, curiously, it is the ultimate club meeting,

where boys of a feather flock together (also girls), out of sight of the rest

of the world.

For all its size, the Convention is intimate, even cozy. Who knows the name of that Other Convention going on next door, like somebody else's noisy party? Some alien race, talking mumbo and jumbo. If you've ever bumbled into the wrong bailiwick, you'll know what I mean. I once went to a large audio press luncheon at a New York hotel, picked up my drink at the bar, sat me down at a table, ate the grapefruit and melon course with relish, and then found I was at the wrong press conference. Dentists or something. Don't remember how I got out, but at the right party (audio) I skipped the grapefruit and jumped right into the roast beef, back on schedule. Two worlds, one floor apart.

Thus, if you want to measure the size and influence of a given field, any one of thousands, the very best thing you can do is to take in their annual or semiannual Convention. Whether it's for model airplanes, or maybe toweling and fabrics, or parapsychology, the rule holds. The Big Show tells all. So it goes in our own area. As you may know, the Audio Engineering Society Conventions are now absolutely enormous, which is a measure of our present and ever-increasing importance.

Of course, the AES, a professional organization, officially does not concern itself with so-called "consumer electronics." But unlike, say, dentistry, our pro and our con (consumer) aspects are so intertwined at every level that, as at the old hi-fi shows, the AES Convention has a fascination for the lay public that you would not believe if you hadn't seen it-witness thousands of high school and college kids who pay good money to jam themselves into the miles of AES Professional Exhibits.

Sometimes I think they outnumber the pros, and maybe it's a good thing, too.

As we always say, the future is theirs. So this past October I armed myself, grabbed a huge breath, took two aspirins, and managed, in one exhausting day, to see at least a hundredth of the AES "do," sprawled all over the huge New York Hilton. (Last year I left a bag at the Audio booth and spent half an hour trying to find the booth again when I was ready to leave.) Even 1% of the show was a lot, and impressive.

After all, no one could see and hear the whole of it simply because there were lectures, seminars, workshops, demos, press meetings and miles of exhibits, all going at once. Unbelievable! Exciting! And such volumes of sheer gab, in every cranny of the place, with average spacing between human sound sources approximately 3 feet. All to the good, I say, and highly educational.

The exhibits are fine-the gab even better. How could anyone go home, i.e., to the larger world outside, not knowing something new and vital? Do I now propose to give you a rundown of leading items in detail, á la Bert Whyte? Not on your life. That would be quite beyond me. Nevertheless, on this very partial look-see and listen, I somehow got a distinct impression of difference this year. There was a new, higher voltage feel, sparked by the startling changes and enlargements of concern now churning up this special world that centers on audio. In previous years, the AES seemed to me much more the "conventional" gathering of specialized pros, especially back in the early years. This is exactly as it should be, of course, in the professional papers and the extensive interchange of highly technical information. But in those first years it was also true of the AES Convention exhibits, which, as I remember, were of relatively minor importance. As time flew on, the exhibits grew and grew in number but still remained thoroughly idiomatic, as we in the music and arts fields would say. I seem to remember, for instance, seeing row upon row, off into the distance, of those huge studio or broadcast mixing boards with their hundreds of sliders and buttons and meters-they were the very mark of professional audio and definitely not the sort of equipment an audio consumer picks up for his home hi-fi system. I cannot ever figure out how these behemoths got into what one might call production, let alone into mass production, and I continue to wonder how so many manufacturers are, indeed, viably in business.

At this last Convention, the big mixing boards were still evident-they are the Grand Central and Penn Stations of our audio network. But there is now so much else available and so much of it novel, if not unprecedented, rather than just new. At least new at our Conventions. Of course, negatively speaking, there might have been a temporary dearth of big boards simply because all those old ones were analog and therefore poison; it takes more than overnight to switch the monsters to all-digital. But, I felt, this was merely incidental. The impressive, overwhelming thing is that the whole complex of digital thinking, plus computer-type development and instrumental control, has brought our audio very far and very fast into relationships with other areas that we formerly pretty much ignored, or merely tolerated.

Audio, I have been aware, is one of the last major "fields" to get involved in, shall I say, chip-itis, a disease that is always hectic, sometimes benign but almost as often auto-destructive, especially in the early stages. It is not so much that we are catching up; what matters is that now we are deeply involved in other people's chip-itis and, necessarily, in other people's equipment too, both professional and consumer and everything in between. TV, video, was merely the beginning. We are now sliding into intimate embraces with those who make optical recordings and perform optical "electronics"; we are almost on hugging terms with the music synthesizer, and with its promoters, designers and users, people who used to be pretty much outside the audio field as we know it. (Yes, they have been around at recent Conventions but definitely with a feeling of being off on their own, guests, so to speak, of a foreign power.) All this is most exhilarating and stimulating! As I write, for instance, I've just answered a press invitation from that impeccably audio-minded concern, Nakamichi-to announce the First Commercially Available Optical Memory System Capable of Recording and Reproducing a Variety of Optical Recording Media (caps are Nakamichi's). Wow--what next? And don't think this won't tie straight into your present "consumer" hi-fi world before you can turn around and buy another amplifier.

Indeed, I recklessly look forward to the first all-optical hi-fi system with not even a trace of electronic signal, and lots and lots of laser power. (Speakers? Well, er, maybe. The impossible takes a little longer.) Several years back, I will now have to mention, I went with a group from the AES San Francisco section on a field trip to visit an elaborate electronic music research lab that is a part of Stanford University. The lecture demo for the audio people had to do with some highly abstruse "pure research" into the exact nature of a few brief bits of recorded sound, which, though playable in a few moments, were occupying numerous man-years of careful study. This in itself was hard to comprehend for the AES people, who, naturally, tended to be either commercial pros or well-versed audio amateurs.

Quite legitimate-it takes all kinds, after all, and somebody has to do the basic research into the nature of sound as we now use it. But what was really disconcerting at that meeting was the total ignorance of each other that these two groups displayed. I confidently presented my "credentials" to the lecturer--he had never heard of me nor of Audio magazine but quickly informed me that I should, of course, subscribe to his official journal, which in turn was totally unfamiliar to me. Ugh. Such a lack of intercommunication. Worse, the lecture (in a cramped, hot room with the air-conditioning system turned off-med-fly spraying) began, to a stunned silence from AES, with a long grade-school explanation of audio fundamentals as though we knew nothing in this esoteric region! Even I was flabbergasted. The AES members were admirably polite, and the lecturer was quite in earnest, but finally, one AES stalwart, sensing the moment, asked a quiet question so profoundly technical that the lecturer was rocked on his heels. All this, mind you, in perfectly good faith--nobody was mad or nasty.

At that point the grade-school fundamentals ceased abruptly and the "real" lecture began. By its end, heat notwithstanding, there was the beginning of some real fraternization. Surprise, surprise! It turned out they had quite a lot in common! And, just incidentally, there was a third element in common which was especially mine--music. Sometimes I wonder whether in all this new excitement the art of music will survive. Like the opera that we kids used to call "The Battered Bride." It was at this same Stanford session, by the way, that another lecturer, a "practical" guy and no advanced researcher into theory, demonstrated what I thought was a really miraculous new synthesizer with memory. That thing could manufacture minutes, maybe hours, of varied music from a handful of original notes, and remember the entire thing. All you did was manipulate the transformations.

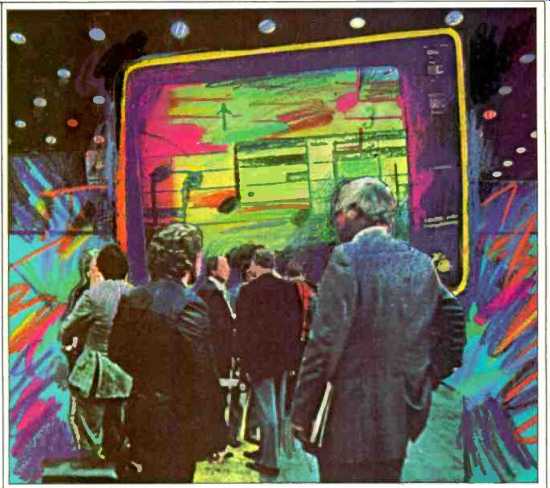

Well, at this past AES Convention, some years after the Stanford visit, there was the same idea but now it was a part of our show. I will mention no brand names because I am aware that there are plenty more of the same general type of music synthesizer with similar capabilities which I have not personally inspected. Suffice it to say that this newer device or, rather, collection of models into various optional systems to taste (or to ear) practically knocked me over. The system not only created, recorded and played back all sorts of elaborate music at length, but it wrote music, displayed it on a monitor, and printed it out on paper in so many notes. So we've come to that! No matter that musical notation is not ever literal but more in the nature of a code with reminders-for those who know. Even so, to play a simple little piece on a keyboard, hear it in sound, watch it grow on a monitor screen full of notes, and subsequently get edited, changed, rehashed-both in the sound and on the screen in notes-is a startling experience for any musician.

The guy at the AES demo took one measure of a Bach Invention and turned it by degrees into a couple of minutes of blues. Right on the screen.

And in playback, out of memory. That's Greater Audio, today, and it happened at our very own Convention.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Jan. 1985; EDWARD TATNALL CANBY)

= = = =