by Ken Kessler

Although the specialist pressings we call "audiophile discs" have been around since the 1950s, the watershed label of the genre has to be mobile fidelity sound lab. When it emerged in the late 1970s, it did one thing that most of the others were incapable of doing: Mobile Fidelity offered killer pressings of famous material.

Instead of some obscure has-been boring you to death with an organ recital or some geriatric jazzer caught near-dead during his last jam, mofi's title included works by the Rolling Stones, Steely Dan, the Beatles, Frank Sinatra, the Kinks, Natalie Cole, and other artists who needed no introduction.

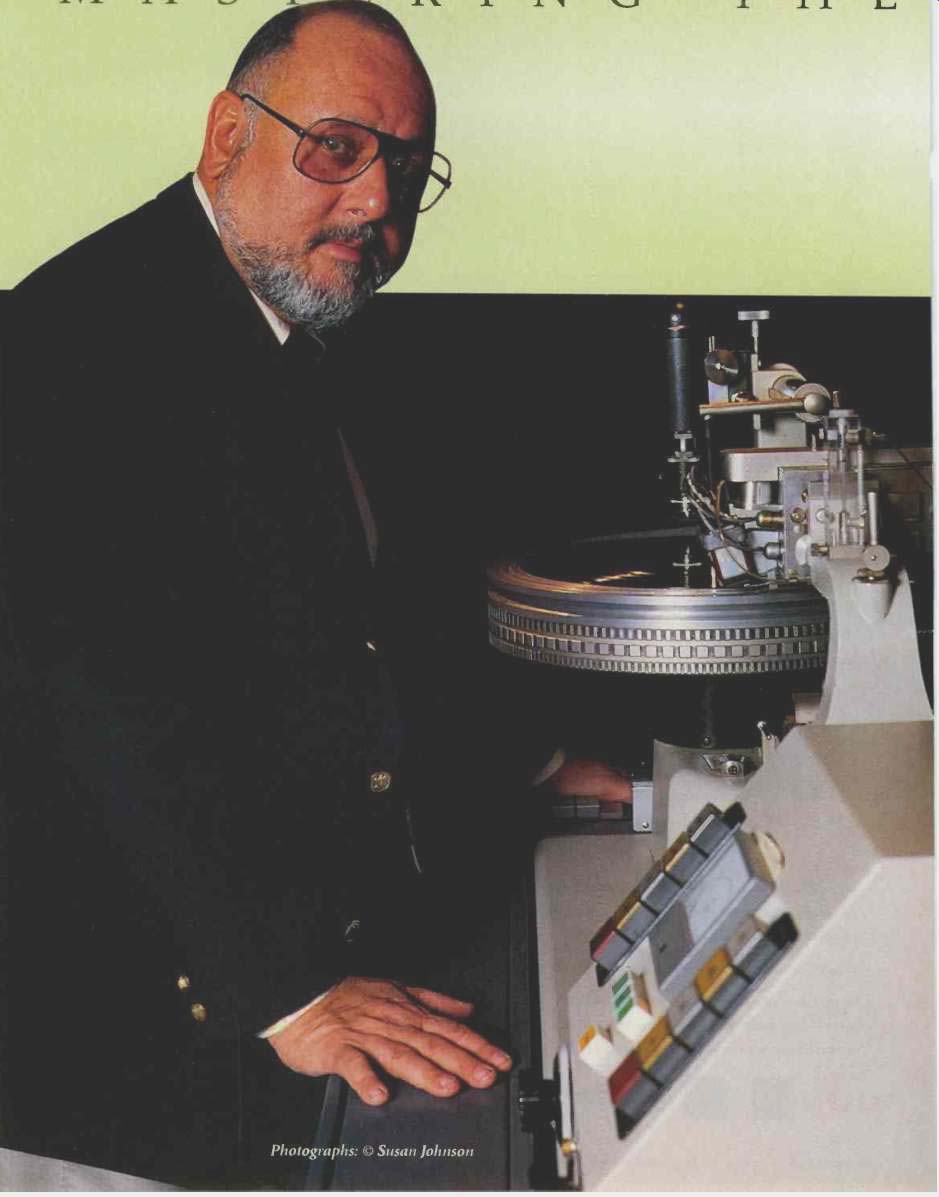

Herb Belkin, the company's president since 1979, has steered the label from its pure analog origins into the digital era and back again, ensuring that mobile fidelity played a major part of what has been regarded as the Lp's revival. He took the time to talk with me at the summer consumer electronics show, discussing in his inimitable manner such topics as the insanity of opening an Lp pressing plant in the 1990s and the continued survival of analog in the digital era.

-K.K.

--------

Before the tape recorder was switched on, we were discussing matters of "audiophile credibility."

And you clarified something that's been troubling me for months, about Mob le Fidelity and how it's perceived. I think we actually do ourselves a disservice by being straight and honest. We don't hype anything. And I think that we've be come a company taken for granted by people like you.

By me?!

No, not you personally. But you've helped me realize something. I'll give you an example. It's not really negative, but this is the reality:

When [names a competitor! leaves the scene--which they will they will have brought nothing to the business other than clever se lection of repertoire and marketing. They're not a technology company, and they have no investment in technology. They rent their engineer, they rent their cutter, they rent their pressing-plant space.

On the other hand, all we do is keep building technology.

We build a record plant, and no body gives a damn. I've gotta tell you something-it's the most unusual record plant on earth. It's built like a CD plant. The few people who have come to it stand there with their mouths open! I can't get anybody interested in it. And you know why? We've been doing this the right way for so long that it's ho-hum to people. It's crazy. And you made me realize it.

People seem to acknowledge that you put your money where your mouth is and made a factory. That has not gone unnoticed.

I understand. But if we ballyhooed stuff and made up lines of bullshit about what we're doing and who we are, we'd get much more attention. It makes me.. .

You're not exactly what I'd call "ignored." You get a large amount of press, more mainstream press than any of the other specialist audio labels.

Only because we're so much bigger. This year Mobile Fidelity will do more business than the rest of the audiophile record industry combined. And it has nothing to do with any of them. It has to do with a perception people have.

But you're almost considered mainstream!

My pet peeve right now is that there's a particular audiophile re viewer whose only bitch with us is that he doesn't like our repertoire. He doesn't talk about the content of what we've done; he's skeptical about why we've picked something. What a stupid thing to do! Let him spend 4 or 5 million dollars on a company, and he can pick the ones he wants.

Perception-wise, and that's the point I'm trying to make, I don't know if there is anything that I can do about it. That reviewer has never written up the GAIN [Greater Ambient Information Network] mastering system, which is much more interesting than any thing anyone else is doing. I look at the coverage of HDCD, and I'm amazed. HDCD is unproven. Nobody has it; there is no HDCD yet!

[This interview took place before the release of the HDCD processed Neil Young Mirror Ball CD and the release of the majority of latest-generation CD players with HDCD-ready D/A converters.] I'm gonna get the fourth or fifth machine, because if it works, I'm gonna integrate it into GAIN. I don't know if it's going to work. Half the people who have listened to the HDCD sampler disc sit there and say it's terrific, while the other half say it's not very good.

It's not been that easy a ride for HDCD.

I don't know yet myself. The chip concept is an excellent idea, and if it works I'll incorporate it into our GAIN program. We've already figured out how to do it, to tell you the truth.

That's what we're about. Every day, we've got to figure out a better way to do what we did yesterday. That's what our job is. It ain't about making money. We're lucky that in the last five years we've made enough to build a plant, to do other things. But nobody re members that there was Nautilus and Direct Disc Labs and Crystal Clear and Sweet Thunder. You know what? There were 22 audiophile record companies between 1978 and 1984--where are they now? Oscar Ciornei of Sheffield Lab told me this morning that he's recording new artists, and Telarc has become a mainstream classical and jazz label. Which leaves us just with Tam Henderson of Reference Recordings. Chesky didn't exist in those days. So it's Reference Recordings and Mobile Fidelity.

When did LPs start to taper off for Mobile Fidelity?

It's simple. In the fall of 1990, I was in Japan for a meeting with the Victor Company-JVC. The managing director of the audio disc plant told me that JVC had come to the decision that the plant where they made our LPs would be torn down and rebuilt as a CD plant. We had six months to decide what to do, to give them some orders and then they would be done. That was the end of it.

At that point we proceeded to order a year's supply of LPs. We mastered some more things and sent them off to JVC, while I went off on an odyssey trying to find a new partner to make phonograph records. I went to Sweden, Switzerland, Japan, Germany, Taiwan, and Korea. Everywhere I went they were closing down pressing plants. I wound up with three choices. There were companies in Switzerland and Bremen, Germany, and there was RTI in California. I chose the company in Bremen.

As we were working out the details of making these high-quality records, PolyGram announced that they were closing down their plant, and they gave all of their pressing business to the company in Bremen. They then turned to me and said, "We don't have time to Mickey Mouse with you." So after spending months with samples and tests, I was out on the street again.

So what did you do?

Now my choices were down to two. I returned to Switzerland, and lo and behold, the plant there had agreed to be the backup for Bremen if they overloaded. So again I'm out in the street. This took me up to early 1993. I then offered to buy into RTI and made Don McGuinness a proposal.

He then told me that he had just signed a contract with Scientology and didn't need a partner. So I said, hey, that's terrific. By now I'm in the latter part of 1993. And then, as so very often happens in life, serendipity entered into it.

I got a call from a guy I had known years before, who said that Westwood One, a radio syndicating company, owned a plant that previously had made records for Nautilus and Crystal Clear. Westwood One had used it tor 10 years to satisfy Army/Air Force net works and their own, and they decided to go to CD. So they told the employees that if they wanted to keep their jobs, they had to find a way to fill the plant up. They called me.

I went down there in a flash and said okay, let's start. Three months go by, and we're beginning to get some fair samples. Then Westwood One was sold to a big radio company.

That took about 60 days, and we then got a call from the guys we were working with. They said, "We just heard they're going to close our plant. They don't care about you. However, we told them that you might be interested in buying it."

I called the head of finance and said, "I'm interested in buying the plant. Give me a number." He gave me a number, we negotiated, and we had a deal. But when I went down there to sign the papers, he announced that they had one change to make. Now, this plant had been in Burbank, California, for 19 years, and they said, "We'll do the deal except you have to take on the responsibility with the Environmental Protection Agency for what's there under the ground." I said, "Excuse me? Who knows what you guys have done?" They did plating there. So I said, "I can't do that." And they said, "We're not going to sell you the plant unless you do that. We have some- body who'll buy it that way." So I said, "Good luck," and I left. Because I knew that couldn't be true.

The guys who were running the place were beside themselves because they could see themselves out of work. About a month went by, and I got another call from the head of finance. He said, "The only way we can sell you the plant is if you accept this responsibility. You didn't get this from me, but if you malty an offer to buy the equipment, I think maybe we can make a deal.

How many pressing machines did they have?

Eight. They were the finest presses made, by 13olex Alpha, a company in Sweden. Two of them were still in the original packing; they had never been used. Two others were the moat recent models that they had made before production stopped in 1984.

Again, serendipity occurred: I could not have made the 200-gram record if I had been in business with RTI. Their presses were not capable of making 200-gram LPs. So I couldn't have done what I wanted to do in the end if I had gone the other way.

In all of life I've discovered that "genius" is generally an after-the-fact phenomenon. Serendipity has really played a great part in the events that have al lowed us to survive and prosper. And this was one of them. I was bound and determined at one time to make a deal with RTI. But we could not have made the record we are making today, which we call the Anadisc 200. I could make a real UHQR (Ultra High Quality Recording) with the presses we have, which is an additional 20 to 30 grams.

Is 220 to 230 grams the maximum that' sensible? Beyond that, is the extra vinyl superfluous?

I think so. My belief is that the 200-gram level [with Anadisc] is going to do exactly what the 220 to 230 would have done without it. That's what I'm hoping. Time will tell. That was the idea; I didn't want to make several forms of records.

In the briefest of terms, please describe Anadisc 200.

Anadisc 200 is the coming together of two different technologies, one having to do with pressing. We use our own vinyl formulation and our own proprietary approach to pressing, manufacturing on a 200-gram record. We press no more than 450 strikes from a set of stampers, and then it's finished. That's the physical end.

The other end, which is how an Anadisc gets to the point of the stampers, is the GAIN system. Nelson Pass designed the electronics, specifically for half-speed cutting, eliminating all of the historic impediments to clear information transmission. We think we have a state-of-the-art system. Normally there's about 42 different stages in the signal path, compared to five with Nelson's work.

So it shortens the signal path?

Absolutely.

And you were immediately blown away by the audible gains?

You bet.

I seem to have gotten us off track and interrupted your tale.

Well, we did arrive at an agreement to buy the Westwood One plant. Mobile Fidelity bought everything in the building that could be moved. We put the entire factory on flatbed trucks, a wagon train that 'vended its way from Burbank to Sebastopol (in Northern California'. It was very quick. But then we put everything in storage. I felt that if we were going to do this, we should do it the right way. I decoded we should design a plant from the ground up, and I wanted it to be as competitive with a CD factory as possible.

All LPs, whether commercial or audiophile, were made in commercial factories, with special attention given when the records were audiophile. We had an opportunity to build the first audiophile pressing plant. And because of the community in which we're located, we could also make it an environmentally friendly one.

It took us six months to build the plant. We have air, moisture, and electrical filtration. We placed certain pieces of equipment in soundproof environments, we brought in the most energy-efficient boilers we could find, and we built our own cooling system. We took every conceivable step to make this, by '90s standards, a state-of-the-art factory for LPs.

Even better than what the Japanese had at the LP's peak?

Oh, yeah. Our Japanese supplier had a great factory, but it was intended to make commercial records and only a couple of presses were allocated to us. It was clean, though, like our factory is. I mean, you can have a picnic on the floor in our factory. You go to any other plant, and the difference is almost shocking. But we went one better:

Nothing goes outside. We recycle all of the water, and there are zero emissions and no leakage from this plant. The technology really didn't exist when the Japanese were making records. This is a 100% environmentally friendly pressing facility. And we return nothing to the atmosphere, to the sewers, the water system--zero.

There is nothing else like this plant. People who have come up have been awed, truly awed.

Are you doing pressing for any other labels?

No, although there are two or three people who we might work with. We look at our plant as an R & D facility. We have not put all eight presses on line; we have four on line right now.

Which came first, Anadisc 200 or the new pressing plant?

They were completely separate. When we brought Nelson Pass, Mike Moffat, Torn Tan, and our own in-house engineers together to start reviewing what would become the GAIN system, we looked at it from every aspect, starting with the tape machine. And that included a path through the digital in and out, as well as a path through the analog outputs. That was the beginning--we were going to do that no matter what, because it was my belief that we would find the right way to make the phonograph record again.

So for what parts of the process do you still have to go outside?

Just two parts. In terms of supplies, we don't make lacquers, which are the transfer vehicle from tape to LP format. That's alchemy it's not even black magic. We have two domestic suppliers, Apollo in California and Transco in New Jersey. Each of them is also a resource for styli, which is the other replenishable aspect of disc mastering. We bring those things in.

The other part is plating. We work with Ed Tobin to create some unique steps in plating. We have a good relationship, a mutually reinforcing one, and he is the best. And again, plating is an art.

[Mobile Fidelity, like Classic Records and some other companies still pressing vinyl, used the services of the legendary Ed Tobin at James G. Lee Record Processing for this crucial stage in production.

Tragically, Tobin was murdered not long after this interview took place. At the request of his clients, Tobin had been training two other employees in the skill of LP plating.]

What was the first LP to come off the presses?

Muddy Waters' Folk Singer. The first records came at the end of 1993; we had to have them in time for the Consumer Electronics Show, shortly after New Year's Day. We pushed ourselves beyond what we thought we were capable of. We made those records, but we didn't feel that we were truly operational until the following May.

What problems did you encounter?

The mistake we made was acting on our own exuberance. We took those first LPs to CES, and we returned with orders. But we then had to make these things, and we weren't that good. We still aren't. This is a work in progress; I don't know if we'll ever be as good as I want us to be. The nature of what we do is that we're. . .unfinished goods. Our reject rate at the time of the Muddy Waters album was 50% for the first quarter. We have now gotten our reject rate down to about 12%. I think 10% is probably attainable.

It all has to do with attention to detail. If the people who are making records don't have the discipline that we require, they don't have that attention to detail. So we literally have to "grow" our own staff. The biggest fights I have in the whole company are with the guy who runs our plant. For 20 years he's been making records, and he thinks we're crazy. We have to quality-control him, and he's the guy who's supposed to be quality-controlling us. It's a great game.

Each of our machines is like a child. They have different temperaments, different personalities. So we're confronted with different kinds of problems. We're currently rebuilding each of our presses, one at a time. We're only going to put six up and will save two for cannibalizing and to use as prototypes if we have to ma chine parts. And if we have the demand, we'll start a second shift.

Some audiophiles would like to think that the future is black and round and analog, and there have been articles in the mainstream press about a vinyl revival.

It's several cult things, a mixture of several different influences. You have these alternative bands, like Nine Inch Nails and Pearl Jam, who want to ensure that their fans have an opportunity to buy a cheaper version of their music, which the LP still would be. That was their belief. They forced their labels to get initial pressing runs in vinyl, which created a certain buzz.

And there still remains a limited digital backlash. I'm not sure it has anything to do with content. Digital, at its inception, promised an exceptional amount that it should never have promised. And people bought into it based on those promises. With a great deal of patience, they waited. And now, more than 10years down the road, a lot of those promises have not been fulfilled. So many people believe that although digital is interesting and convenient and quiet, it is different. After they've had an opportunity to experience analog again, they're not sure that the quiet and the convenience are worth the difference. And that's what this is all about. The LP is not for everybody and is not a threat to the mainstream music manufacturer. The LP is a return to the audiophile's roots, but this is probably less true for the older audiophile than the younger one, frankly.

I've had young people come into our booth at shows, and I've sat them down and played them recordings, A/B'd stuff in blind tests. Every time, they've preferred the LP over the CD. They think I'm lying to them when I tell them the results. We have a store at Mobile Fidelity, and people come out of the listening area talking to themselves. Because they really do hear the difference.

So you're pleased with the response to your return to LP manufacturing?

Absolutely.

How long was Mobile Fidelity without vinyl?

Three and a half years.

Was it hard getting back into selling LPs?

The sad thing is, during that time the nature of retail changed so dramatically. Now we're getting into the sad testimony of what's happened to the retail business, not only in America but in other parts of the world. The guys who are the big users and movers of CD have no interest in the niche business of vinyl, and the hundreds and thousands of small in dependent audio and record retailers have been annihilated by huge super store chains. I have people now whose only role is to search out and find small independent retailers where we can place our LPs. Because as a policy, Mobile Fidelity will not sell its vinyl releases to the chains.

Tower? Strawberry's?

No, sir. If they want to buy them from a distributor, they might be able to do that, but I'm not selling to chains. I feel an enormous sense of guilt in growing and being successful and having left a lot of my independent dealers behind who couldn't compete. This product is exclusively available to specialists. That's the way I want it to be. I want our LPs to be in the hands of people who have collectors and audiophiles as customers, who would use our LPs as reference discs and will also buy them because they're in love with the concept. So, no, we will not make them available to mass merchandisers.

Adapted from Audio magazine Jan. 1996.

Also see:

The Audio Interview: Sheffield Lab's DOUG SAX and LINCOLN MAYORGA (Jan. 1984)