Mobile Fidelity UHQR. Finger Paintings: Earl Klugh. MFSL 1-025, stereo, $50.00.

Just as analog magnetic recording is seeing its finest hours as digital bids to take over, the standard stereo disc, thanks largely to audiophile-oriented record companies, has never been better than it is at present. Even as the compact digital disc prepares its assault, we are witnessing dramatic improvements in the quality of stereo discs. The Japanese Victor Company has been in the forefront of digital development, but as a major producer of records in Japan, they have seen fit not just to maintain their high quality standards, but rather to improve them. Their new UHQR (Ultra-High Quality Record) disc shows just how high the quality level of the stereo LP can be.

Some months ago, Mobile Fidelity announced that they would make certain releases available in UHQR pressings. At a list price of $50.00, they were probably wise to test the market with only a few thousand pressings. Before getting on with a review of one of these discs, I will describe some of the processes which set these discs apart from others.

The replication of a disc begins with plating the master lacquer disc, with subsequent re-plating of metal parts yielding successive generations, including the actual stampers used in the record presses. JVC has slowed down the plating processes to avoid stresses in the build-up of metal. With faster plating, these stresses can lead to groove echo, the familiar and nagging "preview" of a loud attack one or two revolutions ahead of time.

A subsequent operation on the metal parts is the grinding of the backs of the stampers to make them fit snugly to the dies of the record press. Too rapid grinding of the stampers results in deformations in the playing surface which show up as low-frequency rumble and even a minute loss of channel separation. If you hold these new discs up to a light, you will see not a trace of the familiar "orange peel" mottling of the surface. In fact, the UHQR disc bears an uncanny resemblance to a master lacquer in this regard.

The pressing cycle itself normally takes about 30 or 40 seconds. In the process of compression molding, a shot of hot vinyl is forced between the faces of the press to expand outward, filling in all of the minute spaces between the ridges in the stampers, which of course are record grooves in reverse. The slower the molding cycle is, the more accurate and free of ticks and pops the resulting disc will be. In the UHQR disc, the molding process has been extended to about four minutes. The result is almost total elimination of ticks and pops as well as a record free of stress.

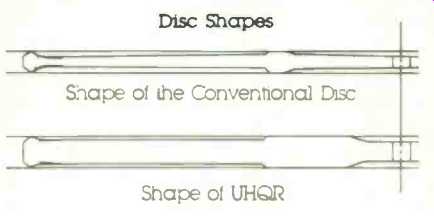

The UHQR disc profile is what records used to have back before the days of "Grooveguard." The disc weighs in at 200 grams, compared with the standard profile JVC product at about 110 grams.

Effectively, the playing area is twice as thick as most current production. This difference is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 Disc shapes.

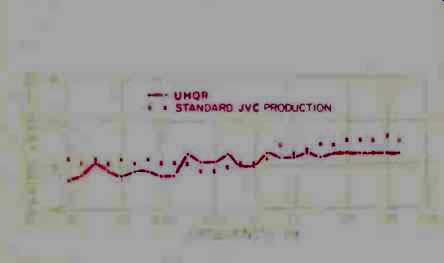

Fig. 2 Lead-in noise spectra (A-weighted at low frequencies; 0 dB is 5 cm/S

at 1 kHz).

The heavier disc is absolutely flat.

You will not see your woofer cones “breathing" every 1.9 seconds in response to once-around warps that are characteristic of standard discs. Another benefit here is the elimination of midrange resonances in the disc itself, which can result from the thin, unsupported playing area of the standard disc.

All of this time and care has been lavished on one of Mobile Fidelity's previous releases: Finger Paintings by Earl Klugh. Dave Grusin's light, airy arrangements make use of a variety of percussion highlights against bass and guitars in quasi-Latin style. String sweetening is tasteful, and overall balances are natural. As good as Mobile Fidelity's standard release of this album is, the UHQR version is even better. With the UHQR, you feel most of the time that you are listening to the master tape. Every 30 or 40 seconds you may hear a tiny click, but for the most part and especially between bands the usual array of disc noises is completely absent. By comparison, the standard Mobile Fidelity release does let you know, especially between bands, that it is a disc.

Another area of improvement should be cited: The level on the UHQR disc is about 1 dB greater than the standard, yet the ending diameters on the UHQR disc are significantly larger. What this means is that the variable pitch and depth system on Mobile Fidelity's lacquer transfer system has been upgraded or refined to make more efficient use of space. A call to Stan Ricker at Mobile Fidelity verified that their new Zuma pitch and depth system was doing what was expected of it.

While on the subject of level, let it be said that Mobile Fidelity product is always cut at moderate levels. Since the noise floor on their product is so low, they can well afford to turn things down and enjoy distortion-free transfers. The UHQR Klugh album has occasional peaks which are 3 dB below normal reference level (7 cm/S lateral velocity at 1 kHz), providing more detail and clarity from beginning to end of a side.

To show the reader just how good both UHQR and normal JVC production are in terms of noise, I measured the noise spectra of the lead-in grooves of the two discs (Fig. 2). Because of the relatively high tangential velocity of the outer grooves, the lead-in portion of a disc is usually quite noisy. Note that both standard and UHQR discs are excellent.

At $50.00 a copy, the UHQR disc is not likely to become a standard. Its greatest utility may be to manufacturers, who are often hard-pressed to come up with decent program material. Obviously, its virtues would be more apparent on classical music than with Earl Klugh. The severest test of all would, of course, be on piano music. Anybody for a UHOR version of Liszt's b-minor Sonata on one side?

-John M. Eargle

Ghost in the Machine: The Police

Nautilus NR40, stereo, $17.00. Sound: A Pressing: A Performance: A

What makes The Police special is how they constantly break all the rules of pop music and make it work for them.

Their songs have inventive shapes and content with often provocative subject matter. Hand in hand with their aggressive song-making, they are a high-tech recording group who don't like to spend a lot of time to make an album. Low overhead and quality product have both been market advantages in their success.

Ghost in the Machine, their fourth album, is the very first pop release simultaneously made available in a half-speed mastered version as well as the "standard" version on A&M (SP-3730). The A&M album is an uncommonly fine sounding album: Clear sound, fine detailing of effects, good flat pressing. The half-speed mastered version adds whole dimensions.

The added presence and clarity in the high end that we have come to expect is a real plus. Stewart Copeland's percussion is a principal benefactor. The stick on-cymbal sound is much sharper. The album picks up an added depth of field and pinpoint placement with apparently wider separation.

There have been artists ill-served by the added clarity of super fidelity albums (Carole King and James Taylor spring to mind). However, The Police's Ghost in the Machine is one of those rarer albums that you really haven't heard right until you've heard the high priced spread.

-Michael Tearson

Beethoven: Piano Concerto No. 5 in E Flat ("Emperor").

Rudolf Serkin; Boston Symphony, Ozawa. Telarc DG 10065, digital, stereo, $17.98.

Let us now take digital for granted as one technique for producing tapes that result in first-line state-of-the-art commercial LP discs (or, for that matter, cassettes). Thus, Telarc's monumental "Emperor" concerto, with the orchestra which was once RCA's and the first-line elder-statesman pianist who was once Columbia's for much of his output, is purely and simply the best current version of this difficult and endlessly long work and one of the finest ever performed in any period. The digital aspect simply needs no comment. It's there, and at its best. The musical value of this recording is far more important.

The "Emperor," last and longest of Beethoven's five for piano and one of those enormous works in the key of E flat which include the unprecedentedly long "Eroica" symphony too (and numerous unusually long works by Mozart as well), is structurally a tough problem for any piano-orchestra team. To keep this monumental music going, especially through the central portions of the sidelong first movement, is nearly impossible. For too many pianists, the thing degenerates into a lot of scales and chord passages; the tension breaks, the shape collapses of its own sheer weight. I had come to think, after many years, that this was perhaps the weakest of Beethoven's concerti and virtually unplayable in a dramatic sense.

But old Papa Serkin (father of Peter Serkin) tells it another way. Miraculously, and without extra fuss, the huge first movement keeps going and does not bog down. Extraordinary! I really have never heard it this way before. I hate to say so, but it would be 99 percent the same for me in an analog recording. So much for our present state of the art.

The Telarc microphoning is ideal, with a clearly articulated piano that is, thank God, neither too close nor too loud but blends and contrasts with the orchestra exactly as the music demands. (This definitely has to do with the excellent musical continuity, the less important piano parts taking their proper subordinate place in the overall sound.) The sonics of Symphony Hall are so well recorded as to be recognizable to anyone who has actually been in that hall in person.

That's good too. And again, none of this has anything to do with digital technique! So be it. Let us hail good music well recorded, whatever the producing technique may be.

E.T.C.

Direct: Tower of Power

Sheffield Lab 17, direct disc, $16.95. Performance: B+ Sound: A Surfaces: A

The big funk sound of Tower of Power is a mighty challenge for a direct-disc session, especially at one that hits up to 125 dB in concert. The wizards at Sheffield have certainly been up to the task.

The TP sound is complex and very dense with the big, big horns six strong up front. They are the star element of the band and can easily overshadow the guitar and organ-dominated keyboards. Sometimes, in fact, just this happens.

The bass has a lively, popping punch, while the drums and percussion are defined and very warm. For raw sound, producer/engineer Larry Brown has admirably handled a tricky, potentially no win situation.

Tower of Power's strength is their great playing. Their material is standard blues/funk fare, with their best shots the instrumental "Squib Cakes" and a live version of their hit 'What Is Hip.” These are the special ones. The essence of direct-disc sessions is to capture performances absolutely live for the best possible sound, hoping to get a magical performance. That's the ideal.

Well, the sound on Direct is exceptional, quibble noted. The horns ensemble as well as Greg Adams' and Lenny Pickett's solos are brilliant. The live energy works for Tower of Power, making the pieces sound better than you'd expect.

Cutting hot puts the best they've got onto the album and that's why Direct is one of their finest moments.

-Michael Tearson

Also see:

Audiophile Recordings: Polished Antiques (Sept. 1982)

============

(source: Audio magazine, Sept. 1982)