Canned Chronicles

By now you have read dozens of accounts of the Orson Welles Panic Broadcast of October 30, 1938, described, in this space last month. Even Mitch Miller, in this very magazine (November 1985), mentions it. Mitch says he was in the studio orchestra that played supposed "hotel" music for the drama of the Martian landings on Earth. Sixty-odd miles to the south, in Princeton, N.J., 10 miles or so from the (supposed) Martians, I was listening to the show, as I said last month. And not believing. Between us, we had it nicely boxed in. Yes, I used to know Mitch, and often watched him oboeing his way through the classics in the notable CBS network broad casts, a counterpart to the Mercury Theatre of Orson Welles. Both were sustaining programs, as they called them then. None of the fancy support from giant corporations and national endowments that we have today. CBS alone paid the bills. But everybody heard the shows.

What continues to interest me is the extraordinary view of radio technique of that time, which the revival of interest in the Panic Broadcast has brought us--thanks, alas, to Orson Welles' re cent death. It is worth a further look, for that was the heyday of big-time AM network radio, entirely without television and minus FM, not only the nation's prime entertainment medium but also its greatest news source--still astonishing us with its literally instant, on-the-spot, live coverage. A thing we had never experienced before. Radio was only then replacing the ancient institution of the newspaper extra for big newsbreaks, rushed off the presses and hawked in the streets by shouting newsboys with their own special lingo: Wuxtry, wuxtry! Read all about it! When you heard that cry you rushed out and bought the huge headlines. It was a thrill, more so than anything on today's TV, which has jaded us for all except the most gory sensations. But radio when radio first produced the remote news flash-had all the old excitement.

In 1938 this sort of instant news was still astonishing, and more so as it cast out further afield with communication improvements. Those magic words, "We interrupt this program to bring you. . . ." were as dramatic in the times of Hitler and Mussolini as any old-time newspaper extra--Titanic Sunk by Iceberg! We heard about Pearl Harbor in one of those interruptions.

It was in a CBS AM network studio that this kind of excitement was put to work as radio drama on that October evening. And thus it was the standard radio sound of the day, realistically conveyed, that set off the great panic.

But how different it all was! In the big centerfold photo in Howard Koch's book on the Panic (see last month), we have, indeed, a visual summary of big radio at its zenith, the Mercury Theatre broadcast on the air, apparently the actual Panic Broadcast it self. The Producer (or whatever he was then called) stands at the rear, script in hand, gesturing. Orson himself. As sorted actors, more or less ill-kempt, ill-dressed, even sloppy looking, lounge in ones and twos around mikes on stands, scripts in hand. Ribbon-type mikes (RCA or CBS equivalent), bidirectional, with an actor on each side.

So unlike any imaginable TV setup! Casual and messy. No huge, looming cameras, no blinding overhead lights, no suspended mikes above, and not a couch in sight. And, of course, no Beautiful People in bright colors. Just that old, comfortable radio slouch I re member so well.

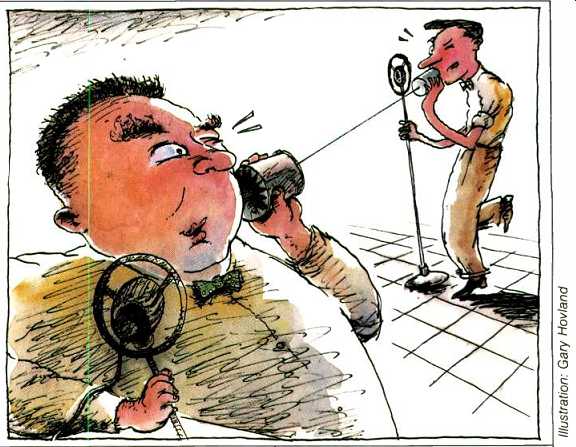

After all, nobody was looking. The entire persona, all the energy, the magnetism, the charisma, went solely into the voice. It could be vibrant, compelling, a veritable Rudolph Valentino of a voice, or name your own female equivalent. But the visible sight was nothing. No wonder people were shocked, visiting a studio, to see the casual slouch and the messy, dun-colored surroundings for all that drama.

When TV came, after the War, there were as many broadcast casualties as in that earlier revolution, the talking movie, but for the opposite reason.

Ugly bodies with gorgeous voices--out they went. Just as the gorgeous bods with the chicken-like voices faded from the movies. TV needed both.

As the old movie stars faded, so did the great announcers and newscasters of radio, into diminishment and de cline. Now we have TV anchors. And Carsons. Good posture. That TV smile! Ever optimistic and bright-eyed. On old, big-time radio, you could scowl and grimace while voicing dulcet words into the mike, and you probably did so when you felt like it.

In that same photo of Mercury Theatre on the air, there are other nice items. To the right is part of a live orchestra, strings. (Mitch Miller must be hiding just beyond the frame.) And a conductor, no less, on a podium-for background music! No music carts, no pairs of tape recorders in the back ground. Music was live, or else. Other sounds, not so visible, were classed as sound effects, and some were wonderful as well as inexpensive. Crumple typewriter paper or, better, the cellophane wrapper from a pack of cigarettes, and you had a roaring, crack ling fire, a conflagration. Horses for cowboys-did you think they trotted them around the studio? Thunder came from a big tin sheet, ancestor of the reverb unit. There were 78-rpm recordings of sound effects, but these were mostly too literal to be real. Real wind sounded like white noise minus the highs. Better a wind machine with a crank. You could have anything you might imagine. Like, say, the sound of Martians.

But the special stunt that the Panic Broadcast pulled off was the radio re mote. The entire show was built, brilliantly, around a series of remote news pickups with brief returns to the sup posed home studio and the hotel mu sic. It was this that struck off the nation wide panic-remember, this was national network broadcasting, heard by millions. As a rule, people kept in touch via their radios, more or less as they do with TV today.

Of course, the "remotes" on the 1938 Panic Broadcast were faked, done in the CBS studio, but they sounded real enough. And they could have been real. The first, for instance, supposedly came from the Princeton University Observatory, the astronomy professor at his telescope, having seen the blast-offs on Mars. An interview--no, not on tape, nor by FM link, nor by microwave. If I am right (and if it had been real), it would have been by phone line (unreliable) or, more likely, via a bulky portable communications station, probably mounted in an old truck. There would have been long cables snaking over the street pavement and up into the observatory, and a microphone way up on the tower be side the telescope. Amazing! One channel, to the CBS building in New York. When all was ready, the announcer would say, impressively, "We take you now to Princeton, New Jersey. Come in, Princeton!" Then, amid clunks and static and hiss, the remote interviewer would get down to business, sounding ever so far away. Instant news, on the spot. Astonishing.

But such formality! Such a lot of verbiage. Radio had not really found its voice. We are far more succinct today, and broadcasting is the better for it most of the time. Nobody now would be fooled by those Orson Welles re motes, but they were precisely realistic for the time. Now, they sound quaint and antique, a residue from the past age of speech-making, minus mikes.

So ponderous, so pompous! Just reading the script, you can sense it.

On every script page, at least four or five segments begin with a formal "Ladies and gentlemen...." Virtually every speech begins with it. "Ladies and gentlemen, we take you now to. . . .

Ladies and gentlemen, we now return you to our studios in New York." And always in that polished, orotund, al most courtly fashion. The announcer did not hurry, even in the very face of the Martians and (supposedly) certain death.

You see, this was a carry-over, right out of the Victorian age, the formal, top-hatted Public Occasion, the rounded, all-acoustic oratory that depended on a sonorous vocal blast to carry to thousands. "Ladies and gentlemen" every speech started that way. Now we hear it only on the most formal occasions--"Mr. President, Members of the such-and-such, ladies and gentle men." A sort of sonic snobbism, but it did persist, if more gently, on into early radio right up to WW II. We still speak to thousands, if not millions. But now each of them is but a few feet distant.

We are more realistic.

Then, in the Welles drama, there were the transitions, from the studio to the remote, out in the field, and back again. So formal! There must have been at least 150 "We take you now to..." announcements in the Panic Broadcast, as there would have been had it been real. And "We now return you to our New York studios." All so courtly and gracious, like a butler in some mansion. It is, in a way, a joy to hear-so old-fashioned. A joy even to read, sound unheard.

Today, for remotes, we just go. We are instantaneously there. No explanations-why bother?--or the minimum, casually. Or we don't go at all-some body just pops up on a screen behind the anchor and they talk, face to face, maybe hundreds of miles apart, or more. Who is where? Often we hardly know. Doesn't seem to matter. Of course, you must get the lingo, under stand the jumps in time and space, the instant replay, the slow motion, the live and the recorded, not to mention the program and the commercials. All are run together, butt-spliced. No transition at all, except for the ubiquitous "Now this ... " Is anybody bothered? I am, sometimes. But then, I'm of another generation. I'm learning. Most people take it all for granted, as they did "We take you now to ... " in 1938.

Indeed, we are so acclimated to this lightning-fast technique that on too many occasions we don't even notice that these slick transitions are bringing us almost nothing at all in the way of content. These people just pass the broadcast ball back and forth--Jim? Bob? Judy?--like some sort of inane volleyball. Fortunately, not all of us swallow this silliness without noticing.

Especially when the news is really important and we are needful.

I groaned, for instance, at the chaotic coverage of Hurricane Gloria on the air, while the storm headed straight at me. So did a high-school senior in New Jersey named Steve Kolb. He wrote a skit which was reprinted in my local newspaper, the Lakeville Journal, in Connecticut. Don't tell me no kids are onto reality! This guy hit the nail on the nose, as I like to say.

Kolb wrote of Hurricane Hogan-the Storm to End All Storms-in, of all places, South Dakota. (He's meteorologically savvy, too.) His anchor news-lady is lovely Lonna Hopponem, and she and her "remote" colleagues at station KOLB trade notes on the hurricane, managing to say precisely nothing about it at all, and a lot about the station's own excellent news coverage.

Here's a condensed bit. First, Lonna:

"Well, Hurricane Hogan is really coming this time ... but for an up-to the-minute report, our own meteorologist, Dick Dunderfuttle. Dick?" "Thanks, Lonna. Well, lucky for us, we just purchased the latest in radar dishes...." "But Dick, how about Hogan?", "Oh, Hogan is really coming this time." "Thanks, Dick. As you know, KOLB's experienced news team. . . ." And so it goes, until Hogan actually hits one of the remote people. Poor Sue! ".. . It's so dark. I've got to get out of here!! No. No, it's too late. We're all going to die!! It's all over!! We're going to "Thanks, Sue. And now to our own roving Ron Rinkersplat. Ron?" "Thanks, Lonna. Dick?" "Thanks, Ron. Well, Hogan is really coming now. Lonna?" And so we take you now to....

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Feb. 1986)

= = = =