BATTLE OF THE BARGE

I have to laugh at the book I am reading, all about the first bungling attempts at railroad-building in England in the late 1820s.

It ties in most oddly with the excitements of recent date concerning R-DAT cassettes. Phew, such arguments, such fights! We are still in the midst of ours to day, as far as I know, with passions galore and much high-minded talk, not to mention threats of preventive action. It'll all work itself out eventually, but first, let me make the strange parallel, before it's too late.

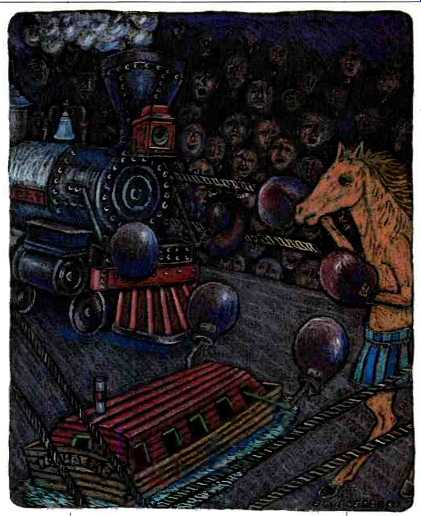

Around 1825, the big flap was three-cornered. In one corner was the horse. In another was the almost-as-venerable (but definitely state-of-the-art) canal boat with its superbly efficient and up-to-date system of locks, up and down in discrete steps, forever flat as well as liquid. And in a third corner was the brand-new steam locomotive, that dangerously combustible and explosive small boiler on big wheels which a number of crackpots were trying to foist on the gaping public, a stinkpot brazenly occupying rails which by every right be longed to the horse. It was a fight to the death, sometimes with guns and may hem, and at the center of it was the venerable steed, representing all that was good, traditional, fair, and reliable in transportation.

Hey, maybe I should send a copy of this book to every producer of recorded sonic entertainment. Some of them are flogging our own horse to death, all with the best of intentions in terms of the dollar.

The first railroad in England, the Stockton & Darlington, opened in 1825 as primarily a coal-hauling system. It was a public highway, equipped with that ingenious new road surface, a pair of iron rails to take flanged iron wheels, or wooden wheels with iron rims attached. Any farmer or coal driver who put the right wheels on his vehicle could drive down this highway as he pleased, and so could the owner of a stagecoach service, all for a modest toll charge. The new steam locomotives could also use these rails, to pull coal carts. If you wished, I suppose you could fit your own private carriage with flanged wheels and take the family for a Sunday drive in the country in new and glorious comfort. No bumps, no rattles.

You could, that is, until you met up with a horse coming the other way, or even a snorting steam machine. In that case, somebody had to back up a half mile or so to the nearest turnout. That was a fatal flaw in the design--in no time there were fights breaking out up and down the highway, notably be tween the horse drivers and the loco motive drivers. Horse trains were left on the track while their owners caroused in a tavern. Carts derailed and blocked the line. There were no signals, no dispatchers, and not even any brakes, other than the usual crude wooden blocks on the carriage or cart wheels. (No, the locos had no brakes at all. You could not even go into re verse, at first.) Chaos? Most certainly not. There was, admittedly, room for a few improvements, but this was the very latest in progress, just like our CD and R-DAT today.

Now, I really hate to say this, but in my fanciful analogy the forces of propriety, law, and the inalienable rights of all concerned are well represented by the horse. The horse was a principle that people believed in, the oldest and most reliable form of transport (next to one's own legs) and surely the fairest-just about everybody had a horse. No body could possibly object to this familiar animal, the very prop of civilized living.

The horse, then, represents for me the copyright law.

Does anybody really object to the copyright law? Of course not.

Then there was the canal boat system. At the time we're talking about, it was at its peak in England (and in the U.S. too), an old but still modern system for the reliable transport of heavy goods, engineered by the 1820s for state-of-the-art efficiency. The canal boat could carry far more than any horse-drawn vehicle on land and with much more safety, yet it did not seriously threaten the horse, which was still its usual motive power.

It had a modern, no-jolt suspension hydraulic, like the remarkable system of locks for raising and lowering vast loads without disturbance. With land roads as they then were, you can imagine how this superb canal system was esteemed by the early industrialists. There were canals everywhere they were essential to industry.

And so, as you might guess, the first railroad people laid out their lines exactly like so many canal systems. Quite literally! Up a steep incline, then flat for as far as possible, then down another incline, all in rigid planes. Preposterous? Maybe so, but it happened. At each inclined plane, there was a land "lock"--a stationary steam engine (in an emergency, horses) and ropes, to haul the goods wagons up or to let them down. As far as possible these inclined-plane "locks" were straight and to an exact grade, at least at the beginning.

Let us continue my slightly zany analogy by comparing the canal system of the 1820s, an old, mature system at its very peak, with--you guessed it--the analog recording system of today and, in particular (for the moment), the old, mature audio cassette system, which is at its very peak right now. The analogy is close, even to the large vested interest and utter respectability of both systems.

As you may suspect, the canal-boat people quickly smelled danger in the new dry-land canal on rails, smack up against their own rights of way, and they began to fight hard-on the highest moral principles, of course. They particularly disliked that irresponsible monster, the steam locomotive, calling it evil, dangerous, filthy, and unreliable.

And they were partly right. In comparison to the steady old horse, which did not explode, the locomotive was in deed a hazardous thing. And so the horse became almost the symbol of opposition. (And isn't the copyright law the center of opposition to DAT today?) No wonder the rail people built their system as much like the canals as possible; they wanted to smooth tempers and allay fears. The railroad was just a new form of an old and acceptable mode of transport. For business reasons, the thing to do was to calm the jitters among canal proponents, and the horse, proposed as drawing power on the new rails, would maybe do it.

You may be sure, the "horse power" faction among the members of the board on each of the early railroads was highly vocal and very powerful.

Let me tell you, the horse very nearly won on numerous occasions--even after the bulk of a new railroad had been completed with all its tracks, bridges, tunnels, and viaducts. (But the canny engineers mostly built for steam, just in case.) I think a much more interesting reason for the "dry canal" concept was that it was simply taken for granted.

People thought in the mode of their own time-we still do today. The canal concept had momentous consequences in engineering terms. It took many years of rethinking before the out-of-date principles were put aside.

Steam was considered and pushed by its proponents-but at first only for the flat stretches of the rail "canals." Reasonable, so long as steam engines could not haul up grades! And so the ropes were taken for granted-one proposal would have had some 30 miles of successive ropes as the main "motive" power.

This curious thinking-as-of-the-present-usage also produced railroad cars that were literally horse coaches transferred to rail wheels. What else? Sometimes there were three or four coaches in a row on one frame. The rounded coach, high and curvaceous, was considered the normal shape for human transport. To this day, there still exist in Europe those compartment cars that evolved directly from the coach on railroad wheels-the name has persisted even where the shape has departed, as in the jet plane.

Pushing my analogy further, I note that steam railroading in 1825 was much like digital recording is today, a revolutionary new technique applied to old requirements. In particular, the steam locomotive is the R-DAT. The parallel breaks down a bit here, since the loco was indeed a shaky and hazardous engineering development whereas the R-DAT cassette system is anything but that, so far as the engineering goes. But people mistrusted railroad performance then much as they have misgivings about digital sound today.

I'm not entirely off the beam in my analogies, especially concerning the horse. I mean, of course, the 1825-model horse, not the nag of today. The equine role in civilization has changed a bit since then. I mean no disrespect to the principles of the copyright-far from it. That law does indeed present a standard of fairness and respectability that is questioned by nobody at all--in principle. The present discussions are entirely in the matter of practicality under new conditions-how to make the law work, fairly and effectively. Adapt, adapt! That's the only way.

It is easy to be virtuous, talking copyright. One can wax very high minded on such matters, as one can concerning that much larger, battered entity, the Constitution. One can al ways defend virtue, and justice, and Basic Rights. True, true, all of it. But again, the real necessity is to adapt. Or else die.

We are adapting already in one sense; the people are showing how they feel, in all their millions. In technically ignoring the general idea of copy right protection, when it comes to video copying in one's home on a not-for-profit basis, the public at large is merely stating that they don't really feel that the idea applies. And I agree. Not, in any case, to the sort of fairly extensive copying covered by the so-called Betamax case. We know it, more familiarly, as Disney versus Sony. It was where the Supreme Court of these United States said that the public did have a right to make tapes of copyrighted TV programs.

One interesting sidelight of this is that there are two readings of the Supreme Court decision. So says a lawyer friend of this magazine. The narrow reading is that the decision applies only to videotaping-as if a video recorder doesn’t have an audio track and can't be used, as with one of Sony's PCM-F1s, for digital audio taping. The wider and (I might add) far more prevalent interpretation is that the ruling applies to all home recording.

Which becomes even more interesting when you consider that Sony has just reached the handshake stage of a deal of whopping proportions to purchase the CBS Records Group, which is the main progenitor of the anti-DAT Copy-code system.

I've given my thoughts on Copy-code in December; let me add only that if you think that millions of Americans are itching to set up as audio pirates when these new DAT machines get to them, you are just plain wrong.

Protection, let us say, might be valuable in a literal sense if the system meant that you simply could not make copies-but if this protection is to be done with even the slightest restriction on R-DAT engineering quality, it is wrong. And shortsighted. Yes, I sup pose a crackpot here and there, or (as in computer information) an 11-year-old genius playing games, might "crack" the protective code, whether the notch sort or the flag type-or somehow disable the whole protective system. But if we can use videotaping as an example, note this: Whether or not the wide variety of protective maskings for videotapes and programs are used, profits have soared for the owners of these copyrights-when the material has been worth copyrighting and protecting.

If I am wrong, I still feel that the wave of the future must continue here, and that we can indeed learn to live with an untrammeled and up-to-date form of home cassette recorder.

There is one obvious point that I have yet to hear enunciated. Okay, suppose we do devise a foolproof no-copy protection scheme for digital recordings under copyright, one that "does not harm the audio quality" in any way. Who's going to buy the digital equipment? Would you buy a VCR if you could not ever copy anything, any time, that the copyright owner did not authorize you to copy--for any reason, good or bad? Not if I know you. Would you buy a non-copying digital cassette system to replace your present audio cassettes? The result would be a drastically diminished market-and who would lose most? The copyright owners, match.

Did you know that in front of every locomotive on that first railroad in England was a prancing horse and rider to lead the way? Propriety, law--but also defiance. Right?

(by: EDWARD TATNALL CANBY; adapted from Audio magazine, Jan. 1988)

= = = =