EDISONICS

The Test of Tests

The only true measure of a sound system's accuracy is how it re-creates reality. So the best test should be a direct comparison between a reproducing system and the live sound source that it hopes to reproduce, right? Well, maybe. I heard a number of such live-versus-recorded tests in the '60s, under the aegis of Acoustic Research. Even without the advancements that have been made in the past 20-odd years, the results sounded very nearly like reality to my newly professional ears, and exactly like reality to many listeners. But I gather that audiences were similarly fooled at the similar demonstrations mounted by Wharfedale's Gilbert Briggs back in the '50s (and in mono, I believe!). And I'm told that they were also fooled by the demonstrations put on even earlier, by Edison.

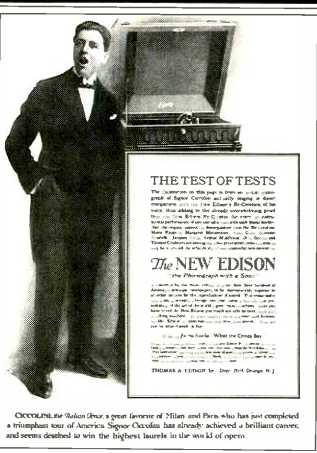

The ad shown here, which appeared in the April 1917 issue of The Ladies' Home Journal, proves only that the demonstrations took place, not that the audiences were fooled by them. Portions of the text read as follows:

The illustration on this page is from an actual photograph of Signor Ciccolini actually singing in direct comparison with the New Edison's Re-Creation of his voice, thus adding to the already overwhelming proof that the New Edison Re-Creates the voice or instrumental performance of any and all artists with such literal fidelity, that the original cannot be distinguished from the Re-Creation. . . .

The NEW EDISON, "the Phonograph with a Soul," is conceded by the mu sic critics of more than three hundred of America's principal newspapers to be incomparably superior to ail other devices for the reproduction of sound. This remarkable new musical invention brings into your home a literally true presentation of the art of the worlds great musical artists. After you have heard the New Edison you could scarcely be contented with a talking machine....

There's more truth than hype in this ad. Little hype is needed, because the audiences at such events-or at any demonstration of a real sonic advance-provide the hype for themselves. As listeners, we are so impressed by the rollback of former unrealities that we temporarily fail to notice the unrealities that remain. The live-versus-recorded comparison is still a good test, and maybe even the best one--but it won't be a perfect test until we become perfect listeners.

And that won't happen soon.

Putting a Lid on a Mystery

Several accessory suppliers sell replacement CD jewel boxes, but most of us need only jewel-box lids.

In the five years since I got my first CD, I've never broken a box itself (though I have cracked one or two), but I must have more than half a dozen boxes with their lids broken.

Somehow, whatever forces break the lids of Compact Disc boxes leave the rest of the box alone. So why must we buy a whole box to get the part we need-and the smaller part, at that? "Because," says Edward Griffin of The Geneva Group, "manufacturers don't make boxes and lids separately." The molds are designed so that both box and lid are made together; selling lids separately would leave the manufacturer with a warehouse full of lidless boxes.

Inaudible Distortion

I keep looking for correlations between what I hear when listening to components and the way those components measure on the bench.

So I was pleased to see what seemed to be some correlation between distortion levels and sound quality among the 10 car stereo units I've road-tested for this magazine: The unit with the lowest distortion (0.08%) on FM stereo was also one of only two I'd singled out for their clear sound. For a moment there, I thought I was unto something.

The only problem was, the distortion of the other units wasn't all that much higher--just 0.22% to 0.85%, with an average of 0.47%.

Looking at it one way, the clearest-sounding unit had only a bit more than one-sixth as much distortion as the average of the others, which should be significant. But looking at it another way, the average difference amounted to a mere 0.39%.

Could this tiny difference in distortion account for the differences I clearly heard? I asked Dr. Richard Small, who is probably best known for his part in establishing the Thiele-Small parameters for speaker enclosures, and who's now head of research at KEF. "We cannot hear distortion," he replied.

Huh? Then why have we been measuring and specifying THD and IM all these years? Because. Small said, distortion is caused by nonlinearity, which is audible.

Distortion, in other words, is not the disease but just an accompanying symptom. We measure it because it's easy to measure, not because it's what we hear. The difference in circuit linearity probably accounted for my perception of sonic clarity.

Sure enough, when I reread my reviews, I discovered that the distortion level of the one other unit I'd acclaimed for its sound was, at 0.32%, right in with the units I had not acclaimed. In fact, the one unit whose sound I'd specifically demurred about (I said it had a high-frequency "edge") had virtually the same level of distortion (0.33%).

To cite THD as the reason for the differences I heard can only be considered a distortion.

Pied Prophecies

Prophets live in hope that people will forget their prophecies. Any prophet will remind you of the ones he called correctly but will leave the rest unmentioned, thank you.

I'm not in the prophecy business as a regular thing, so I don't have to hope as hard for an amnesiac audience. My one real attempt at foreseeing the future came on the threshold of the '80s, when I wrote a piece predicting electronic developments for the decade. How did I do? Well ....

On the positive side, I predicted that the FCC would approve stereo broadcasting for AM and TV, that the French would start substituting computer terminals for printed phone books, and that digital audio systems using optical discs would arrive in '82. I also foretold that flat-tube TV would arrive, but would stay small and expensive for a while, and that video camcorders would be here by '85. Probably my best hit was saying we'd get home ambience systems by 1986 that could simulate specific concert halls; indeed, Yamaha's DSP-1, which at least lets you select the type of hall, appeared that very year. I also foresaw the growth of specialized cable TV channels, though not that some would become less specialized as they matured.

Most of my other prophecies were less accurate. Among other things, I guessed that home appliances, including stereos, would include built in decoders for remote-control pulses sent over house wiring and that they'd also accept vocal commands by 1985. I thought FM stations would discover quadraphonic sound. (It could yet happen, but don't hold your breath.) In video, I said two-way cable systems would become widespread. I overestimated the computer too: We don't have a national mania for interactive computer games, electronic mail competing strongly with the Post Office, or data banks supplanting reference books. However, the number of people working at home via computer link is growing.

In some cases, I was at least half right. I predicted four incompatible videodisc systems, and we briefly did have two; I surmised that videotext and teletext broadcasting would come but not that they'd go away again. Wall-size TV screens are here-but do you know anyone who actually owns one? In some cases, the jury is still out.

Hi-fi systems that could recognize a tune did not come in 1987. Systems that let you alter recorded performances by waving a baton have not been introduced, but at least we have the potential capability to alter pitch and tempo independently.

Flat speakers are not yet hanging on our walls. High-resolution video is definitely coming, and 3-D video could appear.

What do I predict for the '90s? Ask me in '89--or better yet, in '98.

Drawing the Blind

Back in the all-analog '70s, and before, components had controls that worked by feel. Switching was done by buttons that popped in and out with a snap or by multiple-click rotary controls. Variable functions such as volume were handled by knobs or sliders whose position you could figure out by touch. Even meters could be read by touch if you took off their cover plates. To the blind, it was a boon.

Now, what with soft-touch switches and flat-panel volume controls whose settings can only be determined from a display, audio equipment is not as friendly to blind users as it used to be. Digital technology has brought them some helpful conveniences, such as automatic tuning aids and circuits that set recording levels. But in the main, judging from some calls I've gotten from blind audiophiles, it's taken away more than it's given them.

Radio Reminiscences

I'm just old enough to have grown into television rather than growing up with it. Mortimer Goldberg's article in our December 1987 issue ("A Life in Radio Broadcasting") reminded me of the days when programs were staged behind our eyes rather than in front of them.

It also reminded me of a long nostalgia session I had with a woman I was dating, some years back. We were about five years apart in age and discovered we'd both enjoyed the same shows when we were kids:

Captain Midnight, Sergeant Preston of the Yukon, Sky King, and so on. But after the discussion had gone on a while, I realized her reminiscences did not quite jibe with mine: "Hey, wait a minute," I said. "You're talking about television programs!" "Why, of course," she said. "What are you talking about?" "Radio." "Radio?? How on earth could they do all those things on radio?" Actually, they did them very well, using only sound effects, a few scene-setting lines ("Gee it's lonely up here at the lake .... Wait! Put that gun away!"), and the listener's eager imagination. That kind of induced creativity is still used on radio but mostly just for a few ads (and not too many of them, either). A few years back, comedian Stan Freberg demonstrated to radio ad people how creative the medium could be: With a few sound effects, he filled Lake Superior with Jello, covered it with whipped cream, and topped it all off with a 10-ton maraschino cherry dropped from a bomber. On TV, you might be able to do that too, but the budget would be considerably higher.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Feb. 1988)

= = = =