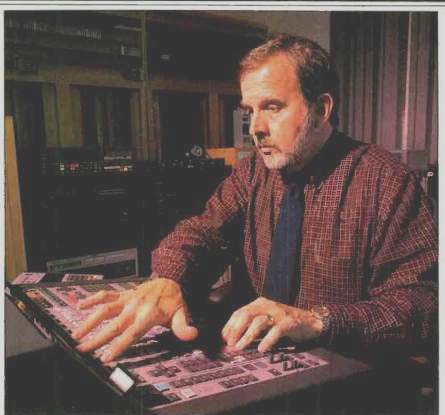

by TOM JUNG

[Tom Jung is president of dmp records in Stamford, Conn.]

By now, almost every one has seen those three capital letters in the rectangle-the SPARS code that appears with virtually all Compact Discs. And almost every one has some idea of what that "DDD" or "AAD" means, but in my experience, those ideas aren't al ways accurate, at least not completely.

Created by the Society of Professional Audio Re cording Services soon after the CD was first introduced, the code's purpose is to indicate whether each step that goes into making a given CD-recording, mixing, and mastering was done in the analog or digital realm. Since all CDs use a digital format, three Ds in the code seem to imply that the music stayed digital throughout the production process, and that a CD with a DDD code gives you the purest sound you can get.

By now, the SPARS code is seen by many CD buyers as a kind of Good Housekeeping Seal of sonic quality.

Some CD booklets include brief explanations of the code, and audiophile magazines are increasingly noting the SPARS code in their CD reviews, an indication that the publications believe readers consider the code an important factor in evaluating a new record.

In concept, I've always supported the SPARS code. I think it's a good thing to tell consumers how the CD they are thinking of buying was made.

In fact, the code is probably a necessity, given the high level of technical sophistication that many music lovers possess today. They do a considerable amount of "homework" to find just the right sound system for playing their CDs; it's safe to assume they also want to know as much as possible about the sonic capabilities of the discs them selves.

On the other hand, I've always felt that the code is incomplete and misleads the consumer who really wants to know if a given CD will produce the best possible sound quality. The SPARS code, as it is currently set up, does not go far enough to indicate the number of times that music is converted from an analog signal to a digital signal, and back again, during recording, mixing, and mastering. Each of these "D-to-A" and "A-to-D" conversions takes a little bit away from the purity of sound that you hear when you listen to the finished CD at home. If you want to know how close the music coming from a CD sounds to the music that was played live in the studio during the original recording session, you have to know how many A-to-D and D-to-A conversions that music really went through.

These conversions exist even for CDs that now carry a DDD SPARS code. The explanations I referred to will tell you that DDD means that a digital tape recorder was used during the recording, mixing and/or editing, and mastering steps. But this does not mean that the music being recorded stayed digital from start to finish.

Here's why:

First o' all, live acoustic music being played during a recording session is an analog signal. During the recording phase-the first D in the SPARS code-this analog signal first enters an analog recording/mixing console and then passes into a multi-track digital tape recorder. In going from the analog console to the digital recorder, the analog musical signal is converted to a digital signal. So right away you've started out with an A-to-D conversion.

In the second SPARS-code D, the mixing phase, the music that has been recorded is played back from the digital tape recorder and, usually, fed into an analog console for mixing. This step requires that a variety of outboard gear--interfaces, input amplifiers, output amplifiers, transformers, etc.--be connected to the recorder.

The use of this additional equipment means that the digital signal stored by the original recorder has to be converted to analog so the out board gear can process it, and then it must be converted back to digital so another recorder can store the final mix. So in the mixing process, there are two conversions--D to A and A back to D--that are not reflected in the DOD SPARS code.

During these two conversions, I believe some of the purity of the original digital signal is lost, never to be recovered. The analogy. I'd use is two people Vying to hold a fairly complicated discussion through an interpreter. Say one speaks English and the other Russian. Person "D" sends out a signal in English, which is then converted to Russian by the interpreter and passed on to person "A." Person A then accepts the signal, in Russian, and sends back a response, also in Russian, to the interpreter. The interpreter converts the Russian signal back to English and transmits it to person A. No matter how good the interpreter is, over time he will affect the meaning ever if only slightly-of the messages going back and forth between person D and person A. The conversation can never be as exact as when D and A speak the same language.

The three "hidden" signal conversions I've just described mean that, to be completely accurate about what really happened to the music during production, the vast majority of CDs coded as DDD should really be coded ADDAADD. The first A-to-D conversion, however, is unavoidable when you are recording a live session, be cause live acoustic music is always an analog signal. No technology currently available can change that. However, it is possible to eliminate the next two steps, the D-to-A and A-to-D conversions, and maintain a pure digital signal all the way to the finished CD.

One way I do that is to produce a recording "live to two-track." In this case, the live music the musicians are playing is mixed on an analog console, and the output of that console is then fed to a two-track digital recorder. The effect is the same as the DDD recording process I described above, an analog signal fed into a digital recorder.

The difference, however, is that the track is already mixed when it is stored by the digital recorder. The next two conversions are eliminated, and the re cording serves as the digital master that becomes the CD.

Another technique is to record the live session on a digital mixer/recorder that allows both recording and mixing without using any outboard gear.

Everything is done inside the recorder console itself, and the music stays digital the whole way. This is one way I do it, and I use Yamaha's DMR8 mixer/ recorder, which has a 20-bit dynamic range, compared to 16 bits for a CD.

This means that we can record, mix, and master above the threshold of the final product-something we generally took for granted when we recorded LPs but have not so far been able to do with CD.

==============

SPARS Code to Be Retired

As we went to press, we received a news release from the Society of Professional Audio Recording Services. The following are excerpts from the release:

Lake Worth, FL-The Society of Professional Audio Recording Services (SPARS) has recommended that the SPARS Code be discontinued. The decision to retire the Code was made during a meeting of the Board of Directors during the AES '91 convention.

"The SPARS Code no longer fairly reflects the complexity of the technology we use today," explained Pete Caldwell, SPARS Chairman of the Board and president of Doppler Studios in Atlanta. "Our discussions began with an attempt to re vise, expand, and update the Code. This quickly led us through a discussion of its present limitations, ambiguities, and mis uses.. . . It became clear that any attempt to revise the code to embrace all of these subtleties and nuances would become so complex as to be meaningless. The SPARS Board therefore concluded that the Code served the consumer and the industry well in its day, but that in its present form, it cannot contain enough data to be a useful yardstick, and that any all-embracing revision would end up looking like rocket science-which, after all, is just about what we have." Skywalker Sound's Tom Scott, who rep resented Board member Tom Kobayashi at the meeting, added: ". . . The code has been in danger of degenerating to simply a marketing device rather than being a useful piece of information to the consumer. I just feel that no code is better than an incomplete or misleading one." "We know the discontinuation of the SPARS Code will be a slow transition," says Pete Caldwell. "We can't require the labels to discontinue using it any more than we could require them to use it in the first place. We can only ask that they weigh the usefulness of the Code, and consider our recommendation."

==============

I'll be the first to admit that I'm obsessed with multiple A-to-D and D-to-A conversions. My experience over a 15-year career in digital recording has convinced me that these conversions are the weak link in the recording pro cess. I was the first producer to use the very first digital recorder, from 3M, on a project with Flim & The BB's back in the 1970s. That experience convinced me that digital was where the industry was headed.

For me, the best digital recordings are made by converting the music to a digital signal as quickly as possible and then staying strictly digital the rest of the way. Not long after that first BB's project, I founded dmp to record exclusively for CD, and to do it with the fewest A-to-D and D-to-A conversions that technology would allow.

Many of you probably know that dmp CDs carry a DD SPARS code. All of our CDs are done either live to two-track or, as is the case with such new releases as Chuck Loeb's Balance, on the Yamaha DMR8. The conversions that normally occur in the middle D of the SPARS code, the mixing process, are bypassed because we either mix before the music ever gets to the digital recorder or we use a digital recorder that can both record and mix internally. By using either method, we eliminate the outboard gear that standard multi-track digital recorders need during mixing, and that requires the music to be converted from digital to analog and back again.

I'm not advocating that the SPARS code should be changed, and to be honest, I don't think it will be changed in the near future. What I am saying is that the code should not be viewed as some sort of sacred cow of sonic purity. It does give you a basic idea as to whether the music was "more" or "less" digital during the process of being turned into a CD. But you need to know more about both the recording approach and the recording equipment used to really know if that CD will give you the best sound you can get.

There's no magic to DDD. In fact and this may sound like heresy coming from me-I believe it's possible to use analog recording techniques and still produce a CD that offers sound quality equivalent to many CDs that now carry a DDD code. How ? By recording analog through an analog console with, say, Dolby SR, which is essentially as quiet as digital, doing the mix on an analog console, and then recording the mix to digital. The code for that would be ADD, but it would sound as good as, or better than, most of today's DDD CDs because this technique eliminates multiple A-to-D and D-to-A conversions.

Finally, whenever the topic of CD sound comes up, I think there's one thing almost everyone-whether you're a recording industry professional or a member of the CD-buying public-for gets too easily: The music. We can all discuss SPARS codes and the technical aspects of recording until we're blue in the face. But the music itself is what makes a CD really sound good and determines whether a disc succeeds or fails. As a producer and engineer, my job is to use the best techniques I know to make sure the music I record sounds as clean and lifelike as possible. But if a tune is really great musically, I could record it on a telephone answering machine and it would probably still be a hit. On the other hand, if the music isn't there, all the Ds in the world won't help.

(adapted from Audio magazine, Feb. 1992)

= = = =