Departments: FAST FORE-WORD, LETTERS, AUDIO CLINIC, SPECTRUM, MONDO AUDIO, FRONT ROW--GAIN 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO.

===================

FAST FORE-WORD

by Michael Riggs

Last week I was poking around in my basement when I came across a box of old open-reel recordings I made years ago. I no longer have the deck-a Pioneer RT-701 that I bought in the late 1970s. It was an unusual, low-profile machine that took 7-inch reels and had nice, peak-reading meters. The recordings themselves were made on quarter-track tape with no noise reduction, mostly at 7 1/2 inches per second but some at 33 1/3 ips. There was a little bit of background hiss in quiet passages, but the recordings were generally very smooth and clean.

In the mid-1980s, realizing that I never played these tapes anymore, I surrendered and transferred them all to cassette. This took a long time and involved some painful decisions regarding side transitions for certain very long recordings. But I did play the cassettes more often than I had been playing the reels.

Whereas open-reel tape was clunky, cassettes were fiddly. If you wanted really good results, you had to have a deck that enabled either automatic bias and sensitivity calibration for individual tapes or metered manual adjustment of these parameters. Even then, the tapes might sound their best only on the machine that made them, especially if you used Dolby C noise reduction. Cassettes are convenient, and they can sound really good-you just can't rely on it.

The advent of affordable, easy-to-use digital recorders has made it possible for audiophiles to have it all: convenience, exemplary sound quality, and consistency.

So what is it about digital recording that makes it so much better than analog recording (particularly analog recording on cassettes)? I think that the answer is, primarily, frequency response. Getting flat frequency response on open-reel tape required that the deck be adjusted properly for the brand and formulation of tape being used, and even then you had to be concerned about treble losses from tape saturation. Pretty much the same story for cassette, except there the dimensions, tape speed, and necessity for noise reduction required almost maniacal precision in setup to achieve comparable results. Digital does away with all that finagling. You put the tape or disc in the recorder, and if the deck is designed and functioning properly, you get amplifier-like frequency response, all the way from the bottom to a little beyond 20 kHz.

When digital recording and the Compact Disc were introduced, the biggest fuss was about the much wider dynamic range that could be captured. No question this is a real benefit, but I think the ease with which truly flat frequency response can be achieved is more significant most of the time. Absent obvious noise and distortion, frequency response has by far the greatest influence on perceived sound quality. So as the responses of more and more links in the production and reproduction chains have been flattened, overall sound quality has improved. Today it is possible to get essentially perfect frequency response all the way from mixing console to loudspeaker input.

Yet frequency response remains one of the biggest challenges in audio. Now, however, it is primarily an issue for transducers: microphones and speakers.

Of course, two transducers have been lost along the way: the record-cutting stylus and the phono cartridge. It was digital recording and playback techniques that made this possible. We have hit the wall with respect to eliminating transducers, however. It seems very, very unlikely that we will ever say goodbye to microphones and speakers. But even there, digital techniques can help by giving engineers the electronic processing power to compensate for mechanical errors. We see a little bit of that already; in the future, I think such processing will explode in both the breadth and depth of its application.

LETTERS

Bennett Nails It...Almost

Rad Bennett's review of the DVD version of Evita (July 1998) closely parallels my view of the movie "in theater." I thought that Madonna did a very good job indeed, particularly since her reading was quite different from Patti Lupone's live theater performance. My only criticism is that I do not think Madonna's voice is quite brassy enough for "Stand Back, Buenos Aires." I had also heard Antonio Banderas on the CD before I saw the movie. He was not impressive, but his on-screen presence is much better. R. L. Promboin Westlake Village, Cal.

Bit of a Discrepancy

I picked up the November 1998 issue of Audio for the first time at my favorite news stand and loved it! Thanks for this generous dose of anesthesia; it made my New York rush-hour subway ride pass seamlessly.

I do have a comment. In his "Equipment Profile" of EAD's TheaterMaster Encore and Ovation A/V preamps, Edward J. Foster wrote: "And instead of Encore's multichannel, 1-bit Crystal Semiconductor DACs, the Ovation has six Burr-Brown PCM1702 20-bit ladder DACs." There are several other instances in this review where Foster mentions I-bit Crystal DACs and their role in the Encore's performance. It seems very odd to me because, according to EAD's own specs (at www.eadcorp.com), the Encore is equipped with Crystal CS4226 20-bit delta-sigma multi-DACs instead of 1-bits. More over, Crystal's specs (at www.cirrus.com/ products/overviews/cs4226.htm) clearly state 20-bit D/A capability of the CS4226.

Although I realize that such a discrepancy has no effect on the Encore's performance, I do not feel comfortable about this fact. Foster seems to infer a conclusion based on technical data (which dominates his review) that Encore's several slightly inferior test results are due to the 1-bit nature of its DACs.

This might appear to be just another rhetorical question about the plausibility of the review, your magazine, and, for that matter, other A/V industry publications. Or perhaps the manufacturers have misinformed the public. I am not ready to infer a conclusion (yet). Alex Bord via e-mail

Editor's Reply: The term "1-bit" is a common, if not necessarily always exact, synonym for "delta-sigma," which is technically accurate for a somewhat wider range of converters that include truly I-bit designs.

What's confusing is that the 1-bit designation refers to how the converter handles data internally rather than to its resolution. (A delta-sigma D/A converter, for example, takes a multibit PCM input, converts it to some form of delta-modulated signal, and then uses that signal to drive a pulse-width or pulse-density output modulator to pro duce the analog output.) That is, a 1-bit converter can have 20-bit resolution, and its performance may be worse than, equivalent to, or better than that of a conventional 20-bit ladder converter. It depends on the individual designs of the converters more than on whether they are delta-sigma or multibit.

Thanks for your interest; glad you enjoyed the mag.

-M.R.

Protect Yourself

I'm writing with the hope that your readers may benefit from my recent experience with a power surge. I returned home after a weekend away to find that a severe storm had caused a power surge in my neighbor hood. It knocked out a telephone answering device, the receiver of a garage-door opener, and three items in my complex stereo system. This system actually contains a dozen interconnected items (not counting speakers); of these, nine were on a surge protector and three were not.

As you can guess, the protected items were fine, but I had to repair or replace the other three. One power amp (a Sanyo P-55) could not be repaired, as the parts were no longer available. It took a month to get things back in order, and the cost of repair and replacement was close to $1,000. That's a lot more than the cost of surge protectors! I now have surge protectors all over the house, especially for the stereo system.

The moral here is that anyone who owns an audio system or any other valued electronic component should have surge protectors to guard these items. It's a very inexpensive form of insurance and will save much aggravation and money.

David Adler Clark, N.J.

Copyright Concern

I'm deeply concerned by new copyright legislation being considered by Congress, legislation that the president is expected to rubber-stamp. The proposed law would give two notoriously greedy and untrustworthy industries, movie and music, carte blanche to totally stomp on the consumer's interests and gradually abolish all forms of consumer audio and video recording as well as our ability to buy infinitely playable audio and video discs.

According to an article in The Miami Herald, the proposed legislation would permit a new type of audio disc to be introduced, one that would be playable only in the first player it is inserted into. The disc would then be electronically "registered" to play solely on that one machine. The music industry's goal would be to force us to buy additional discs for car or portable use, thwarting us from playing the discs at friends' homes and totally wiping out the used-CD market. Such a law could also devastate hi-fi equipment makers, because con sumers could never upgrade to better play back equipment without having their entire disc collections become unplayable.

The day when such a scheme becomes the only way to buy recorded music or video is the day I stop collecting it and kick back and enjoy the substantial collection I already have. There have to be reasonable limits to entertainment industry greed, be fore that industry totally alienates the con sumer. We don't have to buy, you know.

-Phil Cohen; Bay Harbor, Fla.

The Best Medicine

It is always a pleasure to see the Lirpa Labs products listed in the Annual Equipment Directory (October 1998). It never hurts to have a little humor among all the numbers.

-Mike Mihelich, Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

AUDIO CLINIC

by JOSEPH GIOVANELLI

Does Channel Surfing Hurt a TV?

Q. With my entire family running our 32-inch TV, we must change channels hundreds of times a day! I'm not worried about the remote, because I think it can take it, but I am concerned about the set itself Can rapid channel surfing damage the picture tube or anything inside the TV? If that's the case, I'll have to lock up the remote from my four sons or get physical!

-Ron Hutchinson, Earlville, Ill.

A. I recommend that you spare the rod; channel surfing will not harm your TV set. This would not have been true in the days of the mechanical tuner (remember the ones that clicked at each channel stop?). Modern TVs are fully electronic, not mechanical; hence they never get worn or dirty contacts, which in the old sets always meant replacing the tuner. But you might want to keep a spare remote on hand. I have seen remotes fail even when they were used less frequently than yours. Fortunately, re placements are readily available and reason ably priced.

Inadequate Building Wiring

Q. I live in a pre-World War I apartment building that has the original wiring and "upgraded," 100-ampere service. That's 100 amperes (total) for all five apartments in the building. Some of my appliances simply struggle with the inadequate power, but my amplifier frequently goes into protection mode and quits. The rest of the time, the red/green status LED stays red, indicating a problem. Would a voltage regulator help in this situation? I've heard of the Variac, a de vice that I believe keeps line voltage from sagging when powerful amplifiers are tested.

Would that solve my problem?

-Mike Finocchio, via e-mail

A. It appears that your voltage runs rather low most of the time. You are on the right track when you talk about a voltage regulator, but a Variac isn't the de vice to use. Although a Variac enables you to vary the voltage to a load over a significant range and you can monitor the voltage with a voltmeter, thereby letting you adjust it as required, this is not advisable. You may inadvertently set the voltage too high; when the line voltage recovers, your gear may then get too much voltage.

The regulator you need is a constant volt age transformer, connected between the AC power line and the load. It must be rated to handle the total wattage of all the equipment connected to it plus a margin of 25% to 50% as a safety precaution. To obtain one of these transformers, check the listings in the Yellow Pages under "Electrical Distributors" or even "Transformers."

Messed-Up Radio Reception

Q. My new tape deck sits on top of my receiver. When I turn it on to record a program off the air, it messes up the reception. Is there any way I can fix this without relocating the recorder? Would grounding it to the receiver help?

-Mark Stoddard, Sea drift, Texas

AI can't tell from your letter what you mean by "messed-up" reception.

What changes when you turn the tape deck on? Is your problem on AM, FM, or both? Does it occur whenever the tape deck is on, just when its motor is running, or only when you're recording?

Because FM is usually not subject to interference from tape recorders, I assume it's your AM band that's troublesome. In a tape deck, the bias oscillator is always on during recording, and it can be considered as a sort of radio transmitter. The frequency of the oscillator may be 100 kHz, but its harmonics can extend throughout the broadcast band and somewhat beyond it. Because the AM antenna used on most receivers, a ferrite loop, is typically at the rear, it's likely that yours is close to the tape deck. It's not surprising, therefore, that this antenna may pick up spurious signals from the bias oscillator. The problem can be solved by moving the recorder-something you don't want to do. (And, no, grounding it to the receiver won't help.) In the long run I think you should move your tape deck. Not only will the reception problem disappear, but better ventilation of the receiver will result. That, in turn, will help prolong its life.

If you can't or won't move the tape deck, disconnect the receiver's ferrite loop and use an AM antenna located far from the recorder. Ideally, it should be roof-mounted and fed to the receiver via a coaxial line. Alternatively, consider a separate indoor AM loop antenna, positioned well away from the tape deck and connected by cable to the receiver.

Enhancing Home Theater Sound

Q. I realize that we're not supposed to use sound processors-such as equalizers, treble sharpeners, and bass-impact enhancers-in the tape or processor loops of A/V receivers and integrated amps. This makes sense, as the phase changes created by these processors play havoc with the phase-actuated steering circuits of Dolby Pro Logic processing. But it's also a shame. What film wouldn't benefit from a little sonic improvement? How can I use a processor with home A/V gear, and where should the connections be made?

-Kevin A. Barrett, Plainfield, N.J.

A. First off, I'd try using the processors of your choice and Dolby Pro Logic together. The results might not be bad in some cases. But if they are, you can then decide whether a film benefits more from surround sound than it does from other types of processing.

If your A/V receiver or integrated amp has preamp outputs and amp inputs, you could connect processors to those for the main channels, as those connections follow the surround decoder. This may, however, cause an audible mismatch between your main and center channels and another mis match (which may matter less) between the main and surround channels. You can avoid the center-channel mismatch by setting the Pro Logic decoder for phantom-center operation, and you can cure the surround mismatch by using identical processors for each channel and setting them identically.

(Multichannel equalizers for A/V systems are available from several companies, including AudioControl and Rane.) You might be able to put a bass-impact enhancer in the subwoofer line output, as long as the crossover is not below the region where the enhancer searches for harmonics of "missing" fundamentals.

If you already own the processors in question, you have nothing to lose by trying. If not, try to borrow them and try them out before buying.

Too Much Voltage?

Q. Will audio components (especially CD or DVD players) built to operate on Japan's 100-volt AC power lines be harmed by running them on the 110- or 120-volt AC power lines that are the norm in the United States?

-Tao Gu, via e-mail

A. I do not recommend using 100-volt gear on American 120-volt power lines. At best, the equipment will run hot; at worst, electrolytic capacitors may fail prematurely. If any voltage regulators are on the marginal side, they may short, placing dangerously high voltages on micro processor chips and other sensitive parts. I once borrowed a DAT recorder, made in Japan, that was not designed for export to the U.S. Though it was made to operate at 100 volts, it came with a small transformer that stepped the 120-volt AC supply down to the required 100 volts. You may be able to find such a transformer. However, it must have sufficient capacity to handle the power, in watts, drawn by the devices connected to it.

Erasing Audio Cassettes

Q. I have 51-inch speakers in the rear deck of my Honda Accord. If I open the trunk, I have access to their magnets. Could I effectively erase cassette tapes by rubbing their shells back and forth across the face of the magnets, as opposed to using a bulk eraser?

-Name withheld, Houston, Texas

A. Though you might be able to erase cassettes in the manner you describe, the results will not be good. If the speakers are magnetically shielded, there might not be enough magnetic flux to do the job.

Chances are that remnants of the previous recording will remain on the tape, or noise will be added and may persist even if a new recording is made.

If you do use the approach you suggest to erase tapes and you then use one to make a new recording, let it continue to record after the program has finished. This will pre vent noise from being heard at the end of the tape. It would be particularly jarring during a listening session to have the pro gram end, immediately followed by back ground noise and traces of the previous recording.

Listening Fatigue

Q I have a pair of planar-magnetic panel speakers that I can listen to for hours without a break. But when I listen to my conventional dynamic speakers, I need regular intermissions to give my ears a rest. What causes this fatigue or lack thereof?

-Dennis Wren, via e-mail

A. For me, listening fatigue becomes a problem when there are treble peaks in a speaker's frequency response, especially in the region of 2.5 to 3 kHz. The fatigue becomes even more acute when similar equalization peaks have been introduced in a recording by its producer to make the sound more "punchy."

Some drivers, even dome tweeters, exhibit peaks in the range of 2 to 6 kHz that are quite annoying. If these peaks were higher or lower in frequency, their effects would be less audible; indeed, some listeners might even perceive the sound as enhanced on some recordings.

Along these lines, I have experienced an odd phenomenon in my own listening room. It's something that I can't explain, nor can I offer any objective data to back it up, though it seems logical enough. One of my speaker systems has a very slight tendency toward peaky treble response. When it is driven by a really good power amplifier, I don't sense any listening fatigue. But when I switch amplifiers, using one whose characteristics are good but not in the league of the other amp's, I suddenly find the response peaks unacceptable. It gets even more interesting if I switch to slightly better speakers. All of a sudden, the differences between the two power amplifiers are no longer noticeable. I'm not sure how to ac count for this; it may be that we still don't know all of the ways to measure amplifier performance-or that we don't fully know how to correlate what we do measure with what we hear.

Cable Runs in Biamped Systems

Q. In a biamped setup, should the separate cables to the woofer and tweeter sections of the speakers be run parallel to each other or twisted together? Does this matter at all?

-George George O'Sullivan, via e-mail

A. It doesn't matter how you route your speaker wires in a biamped setup. If you use a separate wire for the hot lead and another for the common, you can twist them together or strap them together with tie wraps to keep things tidy.

Although it's okay to run speaker cables parallel to low-level cables that feed the in put of preamps or power amps, it's not a good idea to bundle them together, as this might cause feedback, which, in turn, might trigger system oscillation. The greater the amount of treble boost, the greater the chance of such oscillation. That may seem surprising, but it has happened in at least one instance that I recall. The frequency of the oscillation may be very high-well above the range of your hearing-but it can have such a high amplitude that the tweeters and power amp can be damaged in an instant!

SPECTRUM

by IVAN BERGER

TEST TOPICS: AMPLIFIER POWER

Graphs and measurements can tell you a lot about how a component performs, but only if you know what they signify.

So with this column, we begin an occasional series, "Test Topics," as a guide for novice audiophiles and a refresher for the more experienced. Feel free to send us a note or e-mail message to tell us what topics you'd like us to cover.

Strictly speaking, there's no such thing as a "50-watt amplifier." Your amplifier may deliver 50 watts per channel into a specific load at some specific distortion level, over a specific range of frequencies. But change any of those parameters, and the amp's power output will change.

Therefore, you won't find a single graph of power output in our amplifier reviews. Instead, you'll find a set of graphs illustrating how the amp's behavior changes as each of these parameters is changed.

LOAD IMPEDANCE: When you put a load across an amplifier's out put, the voltage across the output terminals drops and current flows through the load. The lower the load's impedance, the greater the potential voltage drop and current flow.

But the amplifier's output impedance also regulates the voltage drop, and its output voltage affects current flow.

If the amplifier's output impedance is low enough relative to the load impedance, its output voltage won't change much over the normal range of load impedances. Amplifiers with very low output impedances (including most solid-state amps) are, therefore, called "constant-voltage" devices.

Power is the product of voltage and current, and lowering the load impedance makes more current flow.

So a constant-voltage amp will commonly deliver twice as much current into a 4-ohm load as into an 8-ohm load, but it will deliver about the same voltage into either. That's why a solid-state amp's power rating into 4-ohm loads is roughly twice its rating into 8 ohms. (Factors such as the amplifier's power-supply filter capacitance and regulation, and the saturation of its output devices, of ten keep the power from precisely doubling when the load is halved.) Most tube amplifier circuits, how ever, deliver too high a voltage and too low a current to drive normal speaker loads directly. For this and other reasons, they drive speakers through output transformers, which lower the amplifier's output impedance by stepping the voltage down and the current up. For maximum efficiency, these transformers have separate output taps with the proper impedances to drive 4- and 8-ohm loads (and, occasionally, for 1, 2, or 16 ohms). Such a transformer's 4-ohm tap will normally deliver 70.7% of the voltage and 1.414X the current available from the 8-ohm tap, which means each tap delivers equal power into its designed load (0.707 X 1.414 essentially equals 1). That's why a tube amp's power rating usually does not change when you switch to a speaker of higher or lower impedance--as long as you use the proper output transformer tap for each load.

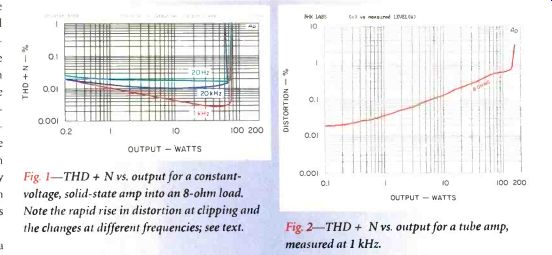

DISTORTION AND FREQUENCY RANGE: The relationship between power and distortion is a bit more complicated. As you near an amplifier's power limit, its distortion goes up. So you could say that the amp tested for Fig. 1 is a 60-watt, a 50-watt, or an 80-watt model, depending on how much distortion you consider acceptable. Its manufacturer says it should deliver 60 watts at 0.1% total harmonic distortion plus noise (THD + N) from 20 Hz to 20 kHz into the 8-ohm load used here, and it obviously does. But had the company wanted to cite a lower distortion spec, the amp could have been rated as delivering 50 watts at 0.002% THD + N.

Makers of inexpensive car stereos and boomboxes-and single-ended tube amps-sometimes rate their products' power only at 1 kHz; with the amp used for Fig. 1, that could have produced power ratings of about 75 watts at 0.0005%, 77 watts at 0.1%, or 80 watts at 1% THD + N. However, when we quote measured power at 1 kHz and 1% distortion, we call it "out put power at clipping," the maximum power the amp can deliver before it reaches the point where it has almost to tally run out of steam. Increasing the input voltage above that point will make distortion shoot up but won't appreciably increase output power, as seen in the sharply rising portions of the curves in Fig. 1.

It's called "clipping" for a reason: If you watch an amplifier's output on an oscilloscope as you feed it a sine wave of increasing voltage, you'll eventually see the waveform flatten a little as the amp clips off the tops and bottoms of the wave. If you raise the input sine wave's voltage high enough, the amp's output will resemble a square wave.

Distortion curves like those in Fig. 1, which mostly stay low but then turn an abrupt corner and zoom upward, signify that the circuit being measured has a lot of negative feedback. The feedback keeps the distortion low as long as possible but can't keep it low forever. (The feedback also keeps output impedance low.) Circuits that use less feedback have gradually rising distortion curves that turn gentler corners as clipping is approached. You mostly see such curves for tube amps (Fig. 2), because few of them use much feedback. (Tube amps use little feedback because their out put transformers can cause instabilities if they're within a high-feedback loop and because negative feedback reduces gain, which tube amps usually have less of to spare.) Here, too, a choice of power ratings is possible: about 150 watts at 0.7% distortion or 70 watts at 0.5%; the manufacturer rated this amp at 120 watts, at which level its distortion is about 0.6%.

Fig. 1--THD + N vs. output for a constant-voltage, solid-state amp into

an 8-ohm load. Note the rapid rise in distortion at clipping and the changes

at different frequencies; see text.

Fig. 2--THD + N vs. output for a tube amp, measured at 1 kHz.

FUDGE, AND OTHER, FACTORS: There are ways, all illegal, to unobtrusively increase a stereo or multichannel amplifier's power rating without increasing its actual power output. One is to feed test signals only to one channel and cite that channel's measured power as the amplifier's power per channel. In most amplifiers, all the channels share a common power supply, so a single-channel measurement lets the tested channel use power that would not be available if the other channels also needed it. That's why amplifiers are normally measured with all channels driven at once.

Another way to fudge the power spec is to lump all the channels' power together, which would make a 50-watt/channel stereo amp a "100-watter." That's seldom done these days, but it's often subliminally suggested by lumping total power into the model number (calling it, say, the "Acme 100").

In the '60s and '70s, when stereo first be came big business, some manufacturers used every trick in the book to inflate their power specs. Eventually, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) clamped down and instituted disclosure rules for rating the power of home amplifiers. Although those rules mandated some specific test procedures, their main effect was to require that every amp power spec be for power per channel, with all channels driven, and that it include-you guessed it-the load, distortion level, and frequency range to which that spec applied. A lot of companies have for gotten this, but it's still the law.

LEGITIMATE DYNAMIC FUDGE: So far, we've been discussing the power an amp can deliver continuously, for long periods of time. But music's power demands fluctuate, and its peaks are usually short. On short peaks, amplifiers can usually deliver more than their rated power. To see how much more, we use the IHF tone burst, a standardized test sequence consisting of a signal that runs at a high level for 20 milliseconds, followed by 480 milliseconds at a level 20 dB lower before repeating. The amp's out put, at its rated distortion, for the 20-millisecond high-level burst is its "dynamic power"-the power it can deliver briefly.

"Dynamic headroom," which sounds confusingly like dynamic power, is the ratio between the amp's dynamic and continuous rated power, expressed in decibels (dB).

"Clipping headroom" is the ratio between continuous power at the onset of clipping and rated power.

MONDO AUDIO

by KEN KESSLER

BROKEN CHINA

Most Americans will likely admit-deep down in side-to not caring a jot about the rest of the planet. Indeed, there's a long tradition of isolationism that nearly kept the United States out of World War H. This tendency rears its ugly little head in between those glorious moments when the country does do a fabulous job of policing the world's trouble spots. (Living in the United Kingdom, I find no greater joy than arguing with Brits who insist that the U.K. could have won the war with Hitler unaided;

they're also the ones still furious with '60s TV shows that suggested American soldiers defeated Rommel in North Africa.) The reason for this preamble is that most Americans usually think about global issues only when they involve military threats and solutions; it's so easy to overlook--or ignore--issues that merely affect the world economy. And in 1999, there is only a global economy.

Though I am no expert on the details of the GATT agreement, I firmly believe in two ultracapitalist tenets: Free, unrestricted trade is a good thing, and isolating one's nation/culture from the rest of the global community is a bad thing.

American isolationism in economic matters is understandable, regardless of the above tenets, because the U.S. is as close as any country gets to being self-sustaining. But the U.S.-based high-end audio industry, a matter closer to our hearts, is far from able to prosper solely on domestic sales; export to foreign territories is a matter of survival. And while the health of high-end audio is nowhere near as important as, say, peace in Sarajevo or the Middle East, this is Audio and not Newsweek, so allow me to pre sent what follows with equal gravity.

A British hi-fi manufacturer sent me a copy of a fax from his Hong Kong distributor. Because of the way the Chinese government deals with criticism, I will not disclose names. The importer, one of Hong Kong's best, deals primarily with American brands and has a reputation without peer. So eloquent is his report that I believe it should be read in the West. True, it deals only with A/V products, but its implications go beyond hi-fi and video.

Some will read it and wonder why he's complaining, because-by selling Western goods in China and dealing with unofficial currency exchange--he's breaking the law. But that's the whole point: No importer should have to endure the trade practices common in China. What follows is the complete text, redacted to protect the privacy of individuals:

I returned yesterday from a two-day trip to Guangzhou, China, and wish to file the following market report to keep you posted on the latest developments in China:

It was warm for a November day in Guangzhou yesterday, but the chill of winter could be felt in the electronic shopping arcades in the Guangdong region. As XXX, XXXXX, and I walked into one of them to visit our dealer, we were met by store workers busily packing up and wheeling away all the imported audio and video equipment that was on display on the shop floor.

As we looked on, store owners who had cleared their shelves began to pull down the roller shutters to close up shop, and in some cases, we saw people pulling down their own company marquees to remove all traces of their having been operating at that location.

Further down the road, the usually bustling sales activity in the small narrow corridors of the crowded arcades has been replaced by bored-looking sales staff sitting around TV sets eating lunch or playing cards.

Gossip spread that tax and customs officers had just raided several shops and arrested some people, along with confiscating their en tire inventory. The word of mouth is that this sweep of illegally imported A/V equipment has reached a new level of intensity and will likely persist for the foreseeable future.

A newspaper reports that staff controlled directly from Beijing has replaced the entire customs leadership in the Guangdong region.

The result is a total blackout of imports from Hong Kong for the last month and a half. As of today, there is no indication as to when shipments can resume.

Later that after noon, we drove to a nearby city called Pan Yu. This city is in the suburbs of Guangzhou and had been the key wholesale area for imported audio and video products for the China market. What we saw was something akin to a ghost town; the shopping malls where loudspeakers used to be stacked to the ceiling and blaring away at full volume have been replaced with a ghostly silence, dimmed lights, and shuttered doorways.

Word on the street is that the key city leaders responsible for turning Pan Yu from a sleepy agricultural village to a trading boom town have been arrested. Pan Yu has been taken over by the Guangzhou city administration, and the freestyle importing and horse-trading of A/V equipment has been eradicated. The fortunes of Pan Yu have an analogy in the mining towns of the American West: Once the supply of gold was exhausted, the thriving activity came to an abrupt halt.

And on that particular day, we bore witness to the fall of the Pan Yu gold-rush boomtown.

Besides closing the smuggling loopholes and chasing down imported products at the retail level, the Central Government has taken on the illegal money exchange that has drained Chinese coffers of foreign exchange.

We read reports of illegal money dealers being executed, and from our own experience we are now charged a much higher rate to ex change RMB to Hong Kong dollars to reflect the added risk to the money-changers.

All this has darkened considerably the out look for business in China during the usually busy fall and winter selling season. The situation is totally fluid, but there can be no reason for an optimistic outlook at this juncture.

By closing down the illegal import trade, Beijing is trying to foster a respect for China's import laws and tax codes. The problem we face is that even if we wished to abide by the law and pay the necessary taxes, there is no avenue open to traders in Hong Kong to undertake a legal trade to import A/V equipment into China! This is a typical Catch-22 situation and one that will prove fatal to many companies in Hong Kong that lived off the China trade during the boom years.

All that is left is to hope that China will soon revamp its laws to allow importation of A/V equipment.

While we wait, we can only count on selling into the Hong Kong market to sustain our business. Bearing in mind that Hong Kong is undergoing an economic downturn of historic proportions, this is no easy task! With the above situation in mind, your sympathy and understanding of our predicament will be greatly appreciated.

Before the more self-righteous among you get all sniffy and start bellowing about how Hong Kong-based A/V vendors are just getting what they deserve because they're breaking the law, let me repeat one statement: "...there is no avenue open to traders in Hong Kong to undertake a legal trade to import A/V equipment into China." This should strike a chord with every one of you who indulges in the current warped fashion for cigar smoking: Hi-fi equipment has be come to the Chinese what Cuban cigars are to American tobaccophiles. We're not talking about prostitution, narcotics, arms sales, or even cancer-inducing weeds.

We're talking about hi-fi equipment. In July 1995's "Mondo Audio," I wrote glowingly of a Chinese hi-fi show, of the Pan Yu district, and of the enthusiasm of China's music lovers. I observed that the country was filled with "1/2 billion possession-hungry citizens, more than adequate cash from who knows where, a lust for Things Western: Levis, mobile phones, Swatches, and, yes, even hi-fi. Drab is out, and China is going to be a market like no other." I went on to say that "The Chinese people, having been isolated from the rest of the world for decades, really did appreciate the effort made by those who visited the show, and the brands involved will benefit directly from the personal appearances by their principal players." But I also found the country to be rife with fakes, undeniably a result of the Chinese government preventing the clean, official importation of genuine articles while turning a blind eye to forgeries made in China. So I asked, "How can these obvious surrogates be marketed so freely? Alas, intellectual property still seems too abstract a concept for many in the Far East." I had been informed that Pan Yu's 350 shops moved in excess of $75,000,000 yearly on two streets alone. Apparently, this has now ceased. There are numerous brands, including American makes, that so depend ed on the Asian market that some weren't even selling equipment at home because they couldn't keep up with demand in Japan, Singapore, Hong Kong, Malaysia, and Korea.

Those markets virtually disappeared last year, and many high-end companies saw sales drop by as much as 40%. And now the one seemingly healthy, untapped market, the territory many looked to as their salvation, has been pretty much closed off to the West. And not for economic but for political reasons.

So here's a hearty welcome to the new, enlightened China.

FRONT ROW

by COREY GREENBERG

GAIN 2: ELECTRIC BOOGALOO

One of the things I find fascinating about audiophile reissue labels is that they al seem to be shooting at different targets when they go back and re-master old recordings. It's a philosophical question every remastering engineer faces: Should you let the original sound speak for itself, or is it better to change its sound so it appeals to certain tastes? If every label in the reissue game has its own "house sound"-and each one definitely does-it's because each approaches the art of remastering with a different agenda.

There's the "Smoke Gets in Your Cutting Lathe" school, typified by Classic Records' Michael Hobson, which goes for a more-vintage-than-vintage sound by arbitrarily warming up the tonal balance with an equalizer and then running the signal through enough tubes to heat a high school gym. At the other end of the spectrum, Rhino's Bill Inglot loves to jack up the highs; the label's got impeccable taste when it comes

ó to choosing its titles, but Inglot's EQ seems permanently set for stun, the 2 end result being CDs that usually sound better on Fatburger CD juke-boxes than on a typical high-end audio system.

Shooting straight down the middle is the approach I think makes the most sense, the "sonic archeology" of DCC's Steve Hoffman. His stated aim is to recover the sound of the original session so exactly that he confers with the engineers who had been there in the first place. He hunts down all the same mastering gear that was used for each particular recording and painstakingly strips away decades of accumulated crud till you can practically hear King Tut scratching him self between takes.

But who's to say what's "right"? The East Coast vinyl rats who shell out 30 bucks a pop for the Classic discs throw 'em on a single-ended triode rig and rasp, "Oh, yeah, dat's da stuff. Jeez, ya know, I re member back in sixty-tree I used to see dese guys play da Vanguard every Tuesday night. Man, dose were da days. Hey, Benny, pass me dat nail clipper, I wanna shell some pistachios...." Meanwhile, the non-audiophile civilians who buy Rhino's Otis Redding

reissues marvel at how "crisp" they sound on their boomboxes and car CD players, while obsessive audio creeps like me, who are interested in hearing what Elvis's and Dylan's master tapes really sounded like be fore the engineers had to dumb them down to fit into a vinyl groove playable by the dime-store changers of the day, sit in front of our modern-day tweaked setups and hear the music much more clearly than they ever did.

There's certainly room for all three approaches, but that doesn't mean anyone's getting rich off them than gold. The market for audiophile remastered CDs is a small one, and it's been a tough few years for these small labels. Though companies like DCC and Mobile Fidelity have always had to work just that much harder to sell their gold-plated super-discs, these overachieving guppies now face a world where fewer and fewer hi-fi huts are really moving their merchandise like they used to. That leaves the main-street shops like Tower, mega-stores that certainly move a lot of Madonna and Wu Tang but can't and don't wanna 'splain to their customers why they should drop $25 on a gold joint when you can skeez the same ya-ya in aluminum for half the price.

In times like these, you find small, high-end audio companies playing it safe, quietly shedding staff, substituting cheap Chinese parts for boutique caps and tubes, and generally paring things down to the nub. So what does Mobile Fidelity founder Herb Belkin do? He pops big money for a whole new CD mastering chain because, "It sounds better, so we've got to have it." And it was reason enough to visit Mobile Fidelity's Sebastopol, California, operation, so I flew in recently for a tour of the facilities and some quality time with both Belkin and mastering engineer Shawn Britton.

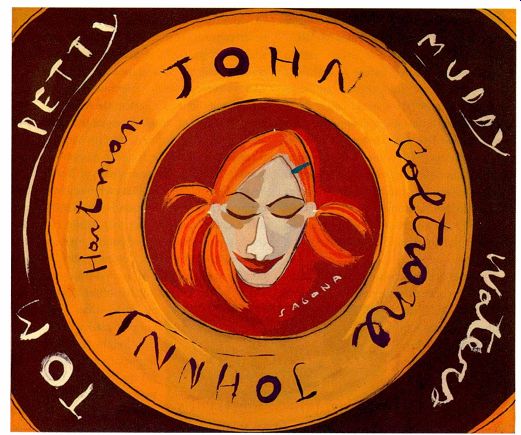

Now, Mobile Fidelity hasn't exactly been getting by with a Radio Shack karaoke ma chine to mint its gold discs. MoFi's original GAIN (Greater Ambient Information Net work) System, designed in 1994 by Mike Moffat of MML Labs and Nelson Pass of Pass Labs, brought a startling improvement to the sound of MoFi's CD reissues that was immediately audible to anyone who heard the first GAIN-mastered reissue, Muddy Waters' Folk Singer (UDCD 593). This state-of-the-art A/D conversion system, using high-precision digital circuitry adapted from military satellite targeting systems, gave MoFi's Britton the ability to transfer every detail of the original analog master tape to the final gold CD, preserving the original recording's sound to a much greater degree than major-label CDs do.

When I heard the Muddy Waters reissue, I said that's it-as far as I was concerned, CD sound could stop right there and I'd never complain again. Whether it was the addition of the GAIN System or just a general refocusing of its operation, MoFi's new CDs towered over its previous efforts, bringing the company back to the forefront of audiophile reissues. But despite the high end's general slowdown, despite MoFi's forced shift from the friendly neighbor hood hi-fi huts to the mean streets of Tower Records, despite the fact that everybody was happy as clams with the sound of the GAIN discs, and despite the fact that Belkin recently took a very large and painful bath on a white elephant of an LP cutting facility he bought at the urging of a vinyl-obsessed writer better known for his blind analog zealotry than his grasp of market realities, Belkin feels it's important to MoFi's future to stay one sonic step ahead of its competitors. And if that step costs many thousands of dollars, he says it's a small price to pay for being able to press the best-sounding CDs on the market.

The GAIN 2 system was a collaborative effort between tube circuit designer Tim de Paravicini of E.A.R. and Ed Meitner of Museatex. Given the task of gutting and re building MoFi's Studer A-80 analog mastering deck, de Paravicini went in and built custom electronics, wiring, and even special low-inductance tape heads whose frequency response goes out flat to 60 kHz, ±2 dB, at a tape speed of 30 inches per second. This particular Studer deck has been modified over the years more times than Cher, but Britton says the current iteration is much more faithful to the original master tape's signal.

Once de Paravicini rebuilt the A-80, he passed the baton to Meitner, who designed a custom A/D converter inserted between the Studer and the Sony DSD (Direct Stream Digital) recording system, which Meitner feels is the most analog-sounding of current pro digital formats. (I'm guessing that when Sony's digital engineers hear stuff like this, they nod their heads politely while their eyes go into the tiniest, most imperceptible roll.) Meitner's A/D converter features an analog input stage made up of Class-A discrete complementary FET cascode buffers, run open loop with no negative feedback. He claims this beefy intermediary stage is necessary to drive the reactive inputs of the delta slope converter, which happens to be a double differential fifth-order modulator. Meitner says the delta slope converter has less of a propensity for emitting idle tones than the more commonly used delta-sigma type. (And if you think I understand a word of this, you're very kind.) As Britton showed me around the GAIN 2 rig in MoFi's main studio, he shared his philosophy about remastering classic recordings. Unlike DCC's Hoffman, who re searches the original sessions and tries to find all the tape machines, mixing boards, and EQs that were used in the original play back system in order to re-create it, Britton uses the same playback chain for all MoFi remastering projects because he feels it's the most accurate setup in existence in terms of getting the audio signal off the analog master tapes he receives from record labels.

Britton's aim, as he described it to me, is to "make the music sound the way it should." In addition to the master tape, he listens to the original LPs and CDs for a reference point, but ultimately it's his own sense of what sounds right and what does not that guides Britton's remastering decisions. As an example, he played me the regular CD of Tom Petty's Full Moon Fever (MCA MCAD-6253) and then MoFi's new GAIN 2 remastered gold CD version (UDCD 735). This is definitely one of the most night-and-day differences between the original' and the label's remastered disc: The gold Fever had a significantly richer, more natural sound than the regular CD, which sounded cold and constricted by comparison. But how does Britton know what the original sounds in the studio actually were? Maybe the instruments and vocals did sound synthetic in the studio-I mean, we are talking Tom Petty here. Britton's response was that as a musician, he knows what drums sound like, what an amplified electric bass sounds like, what guitars sound like. And what he's trying to do is make the master tape sound that way, even if it doesn't sound that way out of the box. It's a very different philosophy from Hoffman's at DCC, but as both guys are turning out some of the most monstrously pleasurable CD reissues on the market, I'll leave the debate to rec. audio. nose. pickers while I enjoy each company's discs on their own merits.

The high point of my visit, however, had nothing to do at all with matters of remastering philosophy. To demonstrate GAIN 2's transparency versus MoFi's original GAIN A/D, Britton had set up a three-way switcheroo so I could compare the sound of an original master tape to the sound of it fed through an A/D/A chain comprising first the former GAIN system and then the new GAIN 2, both converted back to analog audio with a custom-built D/A from Theta.

The master tape? Oh, nothing special just John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman! In critical listening comparisons, GAIN 2 did sound closer to the sound of the master tape than plain-Jane GAIN. It wasn't a night-and-day difference, but I heard more treble air and detail as well as a more see through midrange. To my ears, the master tape had the most sparkle on top, followed closely by GAIN 2 and then the original GAIN. I'll also add that, to my great surprise, I heard differences between the direct feed and each of the two different flavors of GAIN. I've sat through careful listening tests where I couldn't reliably tell the difference between an A/D/A and a master tape or a live mike feed, so I was surprised that I could in MoFi's studio.

But really, who cares about A/D converters when you're sitting there in the same room with the original two-track master tapes of Coltrane and Hartman, listening to the very source tape itself on a high-end playback rig in an audiophile-approved studio?! I'm here to tell you, it just doesn't get a whole lot better than this. I kept asking Britton to roll the tape back so I could hear it again, and again, and again.

"So I can be sure of what I'm hearing," I told him. Man, oh man, you should've heard it. I even rubbed my hand on the tape box, hoping to score some vintage Coltrane fingerprint oil. Definitely one of my all time audio-geek highs.

By the time you read this, Mobile Fidelity should have its gold GAIN 2 disc of this gorgeous-sounding recording on record store shelves (UDCD 740). If you think you've heard this session, whether on the original vinyl or on the recent Impulse! 20-bit remastered CD, you won't believe your ears when you spin the new MoFi. Even with so many killer jazz reissues coming out of the woodwork lately, Mobile Fidelity's remastered John Coltrane and Johnny Hart man stands out from the pack as something truly special. For once, thank God, someone threw megabucks worth of audio overkill at real music.

Thanks, Unkie Herb.

(Audio magazine, 1999)

Also see:

= = = =