by Edward Tatnall Canby

Binaural sound for headphones is on the air! You have read about it in Billy G. Brant's article in our November issue (p. 34) and, earlier, in my own " Midwest Safari" last July (p. 56). In large areas of the country you may now crank up your FM tuner, plug in your phones and hear broadcast sound specifically intended for headphones--not stereo. Binaural. But before we go much further there is a whale of a pile of confusion to sort out as to what binaural is and isn't. Moreover, we have a problem of compatibility, if we are to broadcast binaural software.

Compatibility? Not in the equipment.

In the software requirements, for loudspeakers and for phones. They are very different. True binaural sound, designed for headphone listening, is a law unto itself. You can take down and reproduce sonic situations in binaural that are utterly impractical in the loudspeaker mode. In fact the astonishing power of good binaural is right there--its extra impact in "impossible" situations where normal recording and broadcast techniques flounder. There's no end to the recording discoveries you can make when you set up your own pair of mics and listen back via phones to what you get.

But on the air, this creates its own increasing problem. Because for every FM multiplex listener with phones on his head you will find another, or maybe a half dozen, sitting in front of loudspeakers waiting for something to happen. They aren't aware of the difference.

Or they have no phones--yet.

So every binaural broadcast, now and for a long time to come, must be profitably listenable both on phones and on loudspeakers. That is a contradiction that seems to deny binaural its very best virtues. Oh, so you thought we already had headphone listening, with all those stereo broadcasts and tapes and discs we've been hearing on phones? They call them stereophones, don't they? Ah yes. Confusion upon confusion. Not that stereo via phones isn't an attractive proposition to many listeners. Why else would they be buying phones? Even so, stereo heard in this fashion is only accidentally and in part binaural. (Some of the earliest stereo recordings, done with two mics only, make very good binaural.) The sound of stereo, in all its present complexity, has been specifically developed for loudspeakers. The whole principle is different. You listen in a different way, and it is not merely the physical difference between phones on the head and speakers in the living room.

Via loudspeakers, both your ears hear both channels, as reproduced out there in front by the speakers. The resulting dual-point "fix" in space, to your left and right, sets up the well known stereo phenomenon whereby you seem to hear a smooth spread of sound extending between the speakers and even out beyond to each side (and to the rear in quadraphonic stereo). It's a marvelously useful illusion and a highly satisfactory way of listening.

But binaural is a different alternative.

Inside those phones, each of your ears receives one channel, exclusively, and not a trace of the other. No fixed sources out in front. You are in on the scene itself, hearing directly through surrogate ears, the microphones. If these mics were set up like ears (more or less--we are flexible in perception), a pair of mics ear-close, with maybe a surrogate head in between them, then you are there. With certain important and interesting reservations, you can hear precisely what your ears would hear on the spot. Any spot. Anywhere. In the most unlikely places. Once you have experienced true binaural reproduction, you will not ever forget it.

Yes, normal stereo does give a partially binaural effect through phones, which is enough to account for much of its appeal, over and above considerations of privacy and "surrounded sound". But the whole elaborate stereo recording technique is designed for maximum effectiveness in the loudspeaker mode of listening. Via phones, one channel exclusively to each ear, the effects are both exaggerated and subtly false-out of focus, out of register, confusing. Like looking through wavy glass. You can't pull it all together, it won't quite fuse. The middle is vague and lacking, the sides pull outward, your music threatens to split in two. Individual sounds in the stereo mixdown appear too close, losing contact with the whole. Some sounds, in one channel alone (for one speaker), are heard in one ear and not in the other, and thus are rendered spaceless, drifting unattached inside the head. Like a fly speck on your spectacles. Very annoying.

The more you listen to stereo via phones, the more you will notice these inconsistencies though, admittedly, many of us are not going to let ourselves be unduly bothered by them. Headphones are fun. Nevertheless-they are there, and for good reason.

It follows that if you are out for binaural sound via broadcast, a stereo mic pickup is out of the question. Why bother to call it binaural, if it isn't? Binaural mic pickup uses a single pair of mic "ears" (though more complex techniques are possible). With them, you capture whatever sounds interesting to your ears, anywhere. No special close-up mic technique. No worry about interference noises, excess reverb, overly great distance. Binaural doesn't mind, if you don't. Anything whatsoever that is interesting to hear in the flesh, can be taken down for binaural reproduction. You will not understand how utterly different this microphone technique is until you have tried it out, until you have pushed it to extremes--say recording a conversation in a noisy and crowded cafeteria, or taking down a lecture at a distance of 100 feet or so--just to see how far you can go.

But the further you go, the less possible it is to broadcast your results, where loudspeakers may do some of the reproducing. That is the incompatibility.

Fortunately--if you have begun to digest these somewhat alarming thoughts-there are areas of overlap, where binaural for phones and standard sound for loudspeakers can both be served satisfactorily. It is my intention to analyze these very tricky areas for our mutual gratification. I've done a lot of experimenting and a lot of interested worrying on this score. I've been in binaural myself, off and on, for over twenty years and I am of course delighted that this essentially personal, private, individual way of listening should find a method of simultaneous distribution to a mass audience. That, after all, is basically what broadcasting is all about, even in its normal mode.

My own visit to NCAE ( National Center for Audio Experimentation) in Madison brought me squarely up against these questions. NCAE is in business, already producing a line of finished binaural software directly intended for radio. My first thought was-do they know? Are they even aware of the difficulties of compatible binaural? Had they tackled the problem and found a solution? Or was this just a public-relations gadget? An old cynic, me! Plenty of people have barged into binaural feet first, all thumbs and no head.

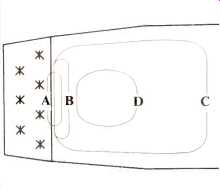

Fig 1--Favorable mic distances: A Favorable mono mic area B Favorable stereo

mic area C Favorable binaural mic area D Optimum binaural mic area

I'm glad to be affirmative. The answer is yes--NCAE knows what it is doing, even if their people don't talk about compatibility. Why should they? They have a product. If they've found a workable procedure to their own satisfaction (they have), allowing for reasonably good loudspeaker playback and yet providing plenty of genuine binaural punch, then why lecture? Get the product out. (The lecturing seems to be my job, and I'm always willin'.) But do not think it is a cinch, this compatible sort of technique for a useful broadcast binaural. They are other approaches quite different from NCAE's. Yours may work just as well. But if you don't know your binaural fundamentals, you won't get far. Or, as I say, you will barge in feet first, and Heaven help you! What, then, are the favorable areas for an overlapping technique, taking in both phones and speakers, within which you must work to develop your own compatible binaural? Here are guidelines.

I. FAVORABLE MIC DISTANCES FROM SOUND SOURCE.

My Fig. 1 shows an idealized conventional indoor source, on a stage. You may extrapolate to your own situation. A and B, sausage like areas, represent areas of conventional mic placement (simplified) for mono and stereo, the stereo a bit further out. C, encompassing virtually the entire space and overrunning A and B, is the favorable binaural mic area for headphone reproduction. D is the optimum binaural, out beyond the loudspeaker mic placement and, perhaps, in one of the "best seats in the hall". What this says is, first, that true binaural reproduction will be acceptable from virtually anywhere in the hall (or other area) where the sound itself is acceptable to living ears. You get what you hear. And, second, that the optimum "best seat" is where it ought to be, well out from the normal loudspeaker mic location. Third: a compatible pickup may thus be made from a position at the extreme outer fringe of the loudspeaker-favorable area or a trace beyond. The binaural sound will then be OK. By manipulation of other factors (below), it can even be quite dramatic and compatible, too.

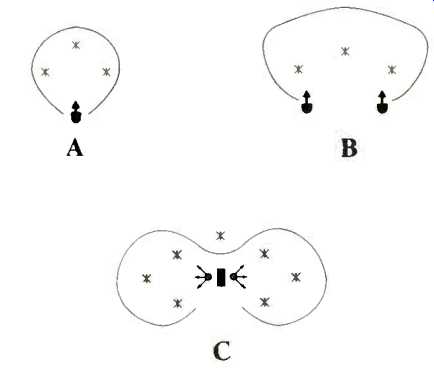

Fig 2--Areas of primary listening interest A Primary mono interest-frontal

B Primary stereo interest-frontal C Primary binaural interest-to the sides

II. DIRECTIONAL AREAS OF PRIMARY LISTENING INTEREST.

Another and different factor. Here there is an astonishing disparity between the loudspeaker areas of favorable directionality and those for headphone binaural. Yet you still may have your cake and eat it.

In Fig. 2, A (mono) and B (stereo) indicate the idealized normal frontal directionality of interest for loudspeaker sound, and the means for micro phoning it, again simplified. Via speakers, program material is always frontal in playback. (Most quadraphonic sound is, too, though by no means all.) And this even though you may actually set up your mics in all sorts of directions, before specially-placed sound sources. Whatever you do, the playback always comes out frontal.

C in Fig. 2 indicated, in contrast, the very peculiar areas of primary interest in headphone listening. They are not to the front, but to the sides. Indeed, front (and rear) directionality, while perfectly clear in the sound, tends to be perceived curiously as overhead, or indefinitely nowhere in particular. Anywhere but out in front. It is extremely difficult to place a binaural sound squarely in front. On the other hand, it is easy and effective-to place it on either side.

This immutable fact of binaural reproduction is still not too well understood though it has been the subject of massive research. The effect is not appreciably altered by a between-mics "head", like NCAE's "Herman", nor for that matter, by "Oscar", a painstakingly realistic German research model head with tiny mics buried inside ear canals. You still hear best to the sides; you are vague as to frontal placement. Even with no "head" at all, just the two mics, your perception is not appreciably different in this respect. To my knowledge, no practical way has yet been devised to bring accurate front placement of sound to headphones. It doesn't really matter, for us at least. You will not notice the lack, if the material is well presented.

You will notice the dramatic realism of any sound off to one side of you.

So-we program for the sides, as well as we can.

Directional compatibility, for phones and loudspeakers, is thus a matter of providing multiple directionalities. Not difficult, once you get the idea. First, your main information must be up front but may be spread out between the normal stereo angles, approximately 45 degrees, though with emphasis on the angled sources, to please stereo listeners. (A correct mic distance is here taken for granted, as per I. above.) Second, other sounds, preferably incidental and small, are added to extreme right and left, beyond 45 degrees. (But never in one channel only!) They should be light enough not to impede loudspeaker listening, which requires low incidental noise, but definite enough to register, dramatically, at the sides of the headphone listening space.

These sounds serve to frame, or set off, the main up-front material, which will be vague in direction in the phones. You have a wide choice-deliberate faint coughs, throat-clearings, rustling of paper, shifting feet, squeaks, scrapes, clinking of ice in glasses, even breathing sounds. Startling, via binaural! Yet, if low in volume, they are not an impediment to communication in the loudspeaker mode. You must use your judgment, experiment.

It depends on the needs of the moment. Just remember (a) to keep your incidental sound effects highly directional, to the sides, (b) adequately low in level, and (c) preferably close at hand. Tiny noises close to one side are absolutely startling in binaural playback.

Directionalities of this sort are normally set up in real time and space, an "instantaneous" recording or broadcast. They may, again, be alternatively mixed down via pan pot techniques and the like. NCAE's prerecorded "sound beds" should be very useful for such situations-but they must be used with extreme care, as NCAE will tell you. Binaural does not like blends. They don't blend, unless very carefully matched.

Note that a wide sound-spread of directional sources is obviously best served by omni mics. For binaural, I use nothing else. They pick up the side information that I want. You may need to use cardioids, to reduce excess ambience (for loudspeakers) or to increase channel separation. Don't expect them to get side information.

You may have to mic the sides separately. But note again that multi-mic, multi-layer techniques are very chancy in binaural, as of present knowhow.

You will be wise to stick to two mics, omni, until you have found out better tricks by experience.

III. OPTIMUM MIC SEPARATION.

Here is an interesting third factor, optional in use, which can be immensely helpful for compatible recording/broadcast of indoor staged events such as concerts. It cannot be used, of course, if your two mics are fixed in their separation by some kind of permanent mount, as in NCAE's "Herman" with the oblong head between.

You will have to eliminate the head--no great loss, aesthetically speaking, especially for music with ambience.

(The head serves in part to cut down ambience.) Your ears will be satisfied merely by the fact of two channels and a binaural separation.

How far apart? How close? The minimum mic separation for binaural effect is astonishingly small. Mics set only an inch or two apart still produce a decided binaural effect in phones.

More practically, you may stretch the separation beyond ear-distance. I have found that in an average indoor hall a distance of three or four feet between mics still produces binaural fusion.

Beyond that, the channels separate, you begin to "hear double" and listening becomes tiring. A real stereo spread-twenty feet or more-is thus out of the question.

But at around four feet, you will Find, you may have a very acceptable loudspeaker stereo (assuming good mic distance again) and binaural too.

While at ear distance, around eight inches of separation, your stereo on loudspeakers is nil, and might as well be mono. So--try "enhanced binaural" as I call it. The binaural effect is of course exaggerated. You are listening, so to speak, with a very swelled head.

But we should all know that exaggeration is the spice of drama! Your "enhanced" binaural will be hi powered and you will keep your loudspeaker listeners happy, too.

With much circumspection, you may try accent or solo mics, to help the loudspeakers where soloists are too distant. (They are OK anywhere in binaural.) Close mics are a familiar device in loudspeaker--intended sound.

But you are likely to get violently unnatural effects in your phones. Your solo singer may suddenly be dangling directly over your head at about three feet distance, bellowing at you as though suspended from wires. That's the sort of thing that happens when you miscalculate your binaural. (Well, if you like it that way, it's all right with me. Just be forewarned ... )

* * * There you have three discrete variables to play with, Mic distance, Source Directionality, Mic Separation.

Each can be manipulated for good compatibility. But the pay off is in their simultaneous use. If all three are optimum, you can have strikingly effective headphone sound and good loudspeaker sound too, with no seeming compromise whatsoever. Most good art, remember, is a matter of canny accommodation--using what you have to maximum effect.

I once made a tape of a choral rehearsal which I throw at you (in words) as a helpful example. There were some hundred singers, sopranos, altos, tenors, basses, seated in a large half circle around the conductor, a piano off behind. The music was Bach's B Minor Mass, and the conductor stopped often to exhort and explain. He has persona, as they say. I wanted him, too, as well as Bach. So I set myself up (that is, my mics) directly to his left, only a few feet from his podium. Here is how I met the conditions I've mentioned for optimum compatibility, though in fact this wasn't my intention at the time. Just experiment.

First, I was about fifteen feet away from the front rows of singers, a perfect distance, in a fairly live big room, for mono/stereo loudspeaker pickup.

A happenstance but a good one. It was also an interesting binaural distance, with plenty of detail sound as well as an over-all blend. As for the conductor, at a few feet he is very much "on mic" for loudspeakers and his remarks are nicely spotlighted. Via phones, at my extreme right, he is overwhelming--he breathes right down your neck. The piano? Nicely background, as an accompaniment.

Second, the singers surrounded me for a full 180 degrees. Thus I had extreme side information, smoothly blended (at equal distance) from one side around to the other. With omni mics, the sopranos were clearly picked up to my extreme left, the basses to the extreme right, the others in between. (You can "tie down" that illusive binaural front area, thus, by hitching it smoothly to the sides.) Between musical numbers, the small rustle of many sounds from the singers all around is superb via phones, reasonably natural via speakers.

Third and most significant, I set my two mics three feet apart. No head between. With such a wide spread of sources, this gave me a very workable loudspeaker stereo, the sopranos easily located to the left, the basses to the right, the conductor just right of center.

In the phones via this "enhanced binaural" mic separation, old Bach really jumps. It is musically one of the most exciting binaural recordings I have ever heard, even though made on relatively primitive equipment. Good for phones and good for speakers.

There's one approach to combined compatibility, NCAE's is another and quite different, in a different area of programming. Yours may be a third, or an n" if you will use these guidelines, listen with your two good ears, and perhaps discover other areas where compatibility can be enhanced. For compatibility we must have, if binaural is to exert its drama on the FM air.

(Audio magazine, Mar. 1973; Edward Tatnall Canby)

= = = =