by HAROLD WEINBERG as told to ROBERT ANGUS

The year: 1952. The place: Palo Alto, California. An aviation engineer we'll call Marvin suddenly began suggesting to his wife that she go visit her mother while he took a week of his vacation. Now, Marvin's wife knew her husband was an audio tinkerer with some pretty grandiose ideas about how to attain the ultimate in sound reproduction in their two-bed room bungalow, but little did she know what he had in mind: A dream horn-loaded loudspeaker system.

Mrs. Marvin's Studebaker was barely out of sight when her husband scurried to a secret cubbyhole in his desk, extracted a blueprint he'd been working on for months, and unrolled it on the kitchen table. Marvin knew its contents by heart. After refreshing his memory on a few details, he set out for the front wall of the living room, sledge hammer in hand.

A few days later he had installed a concrete horn which used the entire wall for its mouth. The horn projected into the front garden and featured a right-angle curve that terminated in a 55-gallon drum buried in the front yard. Driven by a 15-inch woofer installed in the sound-absorbent, waterproofed drum, the horn was painted green and was screened by additional shrubbery planted by the glow of automobile headlights the night before Frau Marvin was due back home.

Having finished the outdoor work and landscaping, Marvin moved indoors to cover the mouth of the horn with tightly drawn fabric and other appropriate decorations placed so as not to interfere with the output of the mid range and tweeter horns. Marvin did the job carefully, and when his wife arrived home, she commented on how attractive the front garden looked.

Then, for some reason history fails to record, she leaned against the living room wall, which proved to be nothing more than speaker fabric.

It is not known whether, in the divorce which followed, she allowed her husband to keep the house

As unlikely as the tale of Marvin may seem, it is only one of hundreds from that crazy period in hi-fi history when every enthusiast fancied himself a loudspeaker designer or sought the goal of perfect 16-Hz reproduction.

The 1950s was a decade given to do it-yourself speaker projects. It was easier to find separate drivers, crossovers and cabinets than complete speaker systems--and, since the art of matching cabinets to speakers was still primitive, your chances of getting the best possible sound were at least as good if you assembled your own system as they would have been if you bought a factory-integrated one.

I'm not quite sure why loudspeakers are considered funny, but even then people laughed at them. The very designations "woofer" and "tweeter" brought smiles to the faces of people whose knowledge of high fidelity was limited to an occasional article in Fortune, The New Yorker or Consumer Re search magazines. Among enthusiasts able to buy woofers, tweeters and midrange units for the first time, no idea seemed too far-out to try.

Result:

An awful lot of very bad sound, some ideas which came to fruition only years or decades later, and plenty of good anecdotes which bring chuckles to the audio fraternity even today.

During the 1950s, I worked as a salesman for several of New York City's leading audio emporia. It was my lot in life to be singled out by would-be creative geniuses who had baroque ideas they wished to execute and needed a pointer here or there, or who had just converted Grandpa's coffin into a folded-horn enclosure and wanted a 26-inch woofer to put into it.

For example, there was the young man from New Jersey who copied the R-J enclosure, a popular one at the time, in welded boilerplate. He had in mind somehow carrying it upstairs, but in the end, since he lived in a large, old-fashioned, three-story frame home, the enclosure had to be brought into his top-floor listening room through the window, using a block and tackle. It weighed almost 500 pounds with a 15-inch woofer installed. According to him, it sounded quite good. I never bothered to check it out for myself.

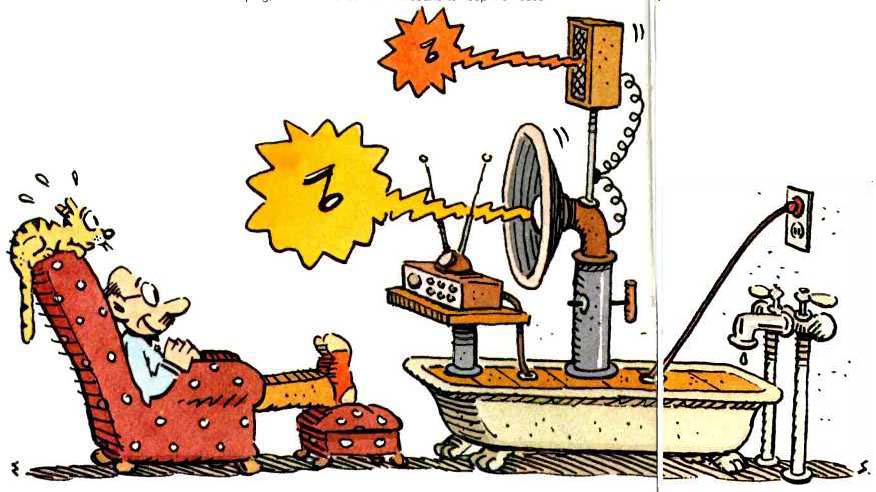

The early 1950s was a time when extensive home and apartment remodeling was going on. Bathrooms, in particular, were targets for weekend do-it yourselfers eager to replace the bilious greens and yellows that had survived through the World War II years. And those cast-iron bathtubs from the 1920s and '30s, the ones with the claw feet, simply had to be replaced with built-in plastic tubs, which meant that just about every scrap yard in the country had more cast-iron tubs than it knew what to do with. They were available free or for a few cents per pound to anybody willing to haul them away. What could be more ideal for a non-resonant enclosure? One of the features of electronics magazines of the period was the do-it yourself project. The pages of Audio and Popular Electronics and Audio-craft were replete with circuits and projects and designs that you could build in a few evenings. Like creating recipes for women's magazines, the effort of coming up with new ideas every month sometimes taxed the inventiveness and imagination of the projects editor who, faced with a deadline, might not have been above dusting off a project a year old and changing one or two parts.

Speaker systems were particular favorites because, for the most part, they were easy for anybody with woodworking tools and experience to build; and required a minimum of technical expertise. Besides, tuner, amplifier and preamp manufacturers who supported these magazines were none too happy at seeing cheap substitutes for their equipment. But speaker makers such as University, Stephens TruSonic, Electro-Voice and Jensen were as interested in selling individual drivers as complete systems, so they were de lighted to have readers see new and creative ways to use their products.

One of these do-it-yourself projects was a grotesquerie known to its admirers as FAS, the Flewelling Audio system. Its heart was a low-frequency en closure, something like an organ pipe.

Like a real organ pipe, it had the ability to produce a single note loudly. The original enclosure was 6 feet long and wide enough to support a woofer 12 to 15 inches in diameter. The woofer was mounted on the outside of the enclosure, and it fired inward. The inside depth of the air coupler was about 6 inches. A slot about 4 inches in height and running the full width of the enclosure was cut into the side opposite the woofer, which was mounted about one-quarter of the way down the length of the enclosure, with the port about 4 inches above it.

With the FAS enclosure, the loading needed to control the woofer's movement was essentially provided by the woofer's magnet alone; the enclosure itself contributed almost nothing. The result was strictly one-note bass, but with a big, loose and sloppy quality the musical equivalent of a big, wet kiss from an overfriendly Saint Bernard dog.

To "improve" the design, some people built a second, longer air coupler on top of the first, with one woofer driving both enclosures. Other people folded the design over on itself. And, as if that weren't enough, some genius came up with the idea of using the space between a building's floor sup ports for an enclosure, boxing it in and mounting the woofer in the basement.

This also permitted the use of substantially longer enclosures; one was 32 feet long and used an 18-inch woofer.

Had the poor fellow who built that monstrosity only known that mounting the same driver in a simple hole in the floor would have produced much better bass and been a lot less work! Or take the case of the mono system with two 18-inch, 16-Hz resonant-frequency woofers. Each was mounted in a sealed 32-cubic-foot enclosure built of 1 1/4-inch plywood, internally braced with 12 two-by-eights per enclosure, and internally covered, before the application of sound-absorbent material, with 2 inches of automotive undercoating to damp any resonances that dared to crop up. It was reported that low bass from an organ seemed to flex the abdominal muscles of listeners.

Many of the more inventive do-it yourself projects were undertaken by money-is-no-object perfectionists willing to spend whatever it took to achieve perfection. But some perfectionists operated on a budget. Take Ernie, for instance, a student at Brooklyn College who regaled me at length, one Saturday morning in the store, about the dodecahedron he'd just constructed from car speakers ripped off from a drive-in movie near Coney Island. Long before Dr. Bose built his first Direct/Reflecting loudspeaker and Design Acoustics its dodecahedron, Ernie had constructed a plywood frame holding twelve 5-inch radio speakers in a roughly spherical configuration. Time has mercifully clouded whatever details Ernie supplied about wiring together these unappetizing elements, but I do remember that there was no bass reproducer. The store was unusually busy that day, but that wasn't my only reason for resisting his invitation to hop over to Brooklyn and hear his creation.

Another customer, named Sid, purchased one of the first packaged component systems, put together by Lafayette Radio. It consisted of a General Electric variable reluctance phono cartridge, Brociner amplifier, Collaro record changer, and Electro-Voice SP12B coaxial speaker. The price was

$99.95, a princely sum for many a young audiophile at the time, and the speaker came without an enclosure although Lafayette would sell you one for an extra $30. Sid wasn't about to pop for the extra money. His fifth-floor Greenwich Village walk-up had a bricked-up fireplace which could be pressed into service. Sid took his purchase home, stopping by a hardware store to pick up a hammer, chisel and some quick-drying cement. That night, he unblocked the fireplace grate, mounted the speaker in the opening, and sealed the wall back up. The perfect infinite baffle, he thought. And it would have been, had not every tenant in the building who shared that chimney started banging on Sid's door to complain about the vibration.

-------The plastic bathtub boom of the '50s filled scrap yards with iron tubs that made ideal, non-resonant speaker enclosures.---------------

Much of the action in New York audio in the early days took place along the narrow streets of lower Manhattan on Saturday mornings, when the ferries from New Jersey would bring loads of shoppers hunting for bargains along Greenwich and Cortlandt and Liberty Streets. Audiophiles would pick through the parts displayed on open tables on the street or cast lustful glances through the windows of Airex Radio or Terminal-Hudson at the newest in pickups, power amps, or multi-cellular tweeters. On the corner of Greenwich and Cortlandt, a spot now buried beneath one of the twin towers of the World Trade Center, Can tor the Cabinet King was likely to have just what you needed to house that horn tweeter and public-address speaker you'd just rescued from the war surplus bin at East Radio.

Cantor once asked me to help him build a speaker system into his basement. Not for him the petticoats once worn by a Stromberg-Carlson console or a Trav-Ler TV receiver, the merchandise he offered his customers. The Cantors, it seemed, loved to dance, so the Cabinet King wanted to create a Make-Believe Ballroom in his basement. We partitioned off one end of the basement, installing studs and a false wall of 3/4-inch plywood into which we cut holes for six-count 'em, six Wharfedale loudspeakers and a Tech Master black-and-white TV set. Long before anybody ever dreamed of integrated audio and video systems, and even before most people had thought of stereo, the Cantors were entertaining their friends with a TV screen mounted in the wall and flanked by identical pairs of woofers, tweeters and midrange units. We channeled the TV sound through an amplifier in the room to both sets of speakers, and Cantor, at least, seemed highly pleased with the results.

Another incident was before my time, but it's still a favorite story among Cortlandt Street veterans. One busy Saturday morning before World War II, when the Sixth and Ninth Avenue elevated transit lines still ran down Greenwich Street, a man and his son huffed and puffed their way to the front of one of the stores, lugging between them an enormous theater-style speaker system. A salesman stepped from behind the parts counter and offered to help them to their car. "We don't have a car," the father explained. "We've got to get it up to the el." The salesman obligingly took up the rear as far as the station steps. On his way back to the store, he saw his boss, red-faced and panting, charging toward him. "Where did those guys go with that speaker?" he demanded. The salesman pointed to the figures now near the top of the structure, where the Ninth Avenue trains pulled in. "They didn't pay for it!" the boss shouted, and together he and the salesman huffed their way up the three flights of stairs-just in time to see the train pulling out with its precious cargo of loudspeaker.

New York City's Transit Authority had a strict rule about what could and could not be carried on the subways.

"This isn't a freight service," the exasperated token-seller at the Cortlandt Street station told more than one audio shopper. In fact, nobody in the transit system ever envisioned the kinds of things people would try to squeeze through the turnstiles and onto the trains-console radio-phonographs in the early days, and late on Klipschorns and console television sets.

There was a rule that everything had to be wrapped, so we'd throw sheets of newspaper around some of the bulkier items and tie them up with string, in an attempt to conceal what was inside. A favorite ploy of some shoppers was to come down on Saturday morning with a friend and a child. While the child distracted the attention of the man in the token booth, the two adults would try to hoist over the turnstile barrier whatever they had just bought, from a rooftop TV antenna to JBL Ranger Paragons and E-V Patricians.

I sold a particularly elaborate television antenna one day to a resident of one of the farther-out suburbs. With a perfectly straight face, he asked me to cut it in half so he could get it past the turnstiles and onto the subway. I checked with my boss, who suggested we get the man to sign a release, absolving us of any responsibility and noting that we wouldn't take the antenna back if it didn't work. Then I got out a hacksaw and cut a perfectly good deep-fringe antenna into parts small enough for the customer to tuck under his arm. I heard no more about it, but I often wonder how he enjoyed putting it back together again, and what kind of reception he got.

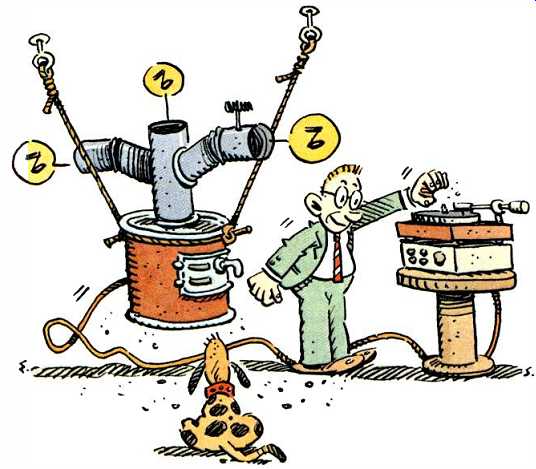

----------Why are loudspeakers considered finny? Maybe it's the mad ingenuity of the early models, maybe just the words "woofer" and "tweeter."---------

In the 1950s, the customer was al ways right, and at Harvey Radio we treated ours like kings. A strong seller at the time was the Wharfedale system in a sand-filled baffle. Other shops might fill their baffles with common gar den-variety sand, but ours had sand specially cleaned for use in sandboxes. If you bought your Wharfedale SFB (sand-filled baffle) system from one of those other shops, who knew what bugs or other undesirable flora or fauna might be mixed in with the sand?

------------Speakers can make funny noises sometimes. But why did two pairs make noise when their stereo systems were turned off?----------

A frequent problem while I was at Harvey-and probably at a number of other audio salons around the country--was speakers whose voice-coils had melted and whose cones had burned to a crisp. The cause, as often as not, was an audiophile's bright idea to use an ordinary a.c. extension cord to extend speaker lines. In those days, speaker lugs and phono plugs weren't available from every corner hardware store, but a.c. wall plugs were. So some of our customers bought wall plugs, male and female, and attached them respectively to speaker leads and the terminals on the back of the amplifier. Invariably, some well-meaning soul would discover one of these wall plugs unconnected and insert it into the nearest outlet. There would be a terrifying sound and the smell of burning insulation and paper, and one more loudspeaker system would be on its way back to us. Occasionally, the male plug was on the amplifier, in stead, and the amp would become a room heater for a very short time.

In the early days of audio, the materials used to make speakers presented some unique problems. Cloth and rubber were favorite materials for loud speaker surrounds, but each had its drawbacks. Rubber would dry out and become brittle, or would offer too much or too little resistance.

The Lowther, a British speaker, was one of the first to use plastic in its cones. The science of polymers in those early days left something to be desired, and every Lowther system we sold eventually had to be returned to the factory to have the cone remounted when the synthetic material dried out.

We had one customer who complained of a rattling sound inside his Wharfedales even when the stereo system was not in use. I spent the better part of an hour with him on the phone, eliminating first one component and then another as the possible source of the problem. Finally, after we had eliminated everything else, I asked him to bring the speaker in. It turned out that a family of mice had made their home in it, and had been dining on the speaker's cloth surround.

Another speaker which produced distortion even when the amplifier was disconnected belonged to a man who lived in one of the small towns down toward Princeton, N.J. I went through the same kind of step-by-step elimination with him that I had done with the Wharfedale owner. We'd talk during the day and find nothing wrong. That night the problem would be back, and the next day we'd eliminate another component. This went on for some time, and I asked him to bring the speaker in. We checked and double-checked it and still could find nothing wrong. So he invited me out to the house for dinner and an evening of listening to music.

One look at the house, and I had a sneaking suspicion what the trouble might be. It was a masterpiece of Victoriana, straight out of a Charles Addams cartoon--with the exception that it was tastefully, even luxuriantly furnished. After dinner, we got down to business with the hi-fi system. Before long, I could hear it-a distinct knocking in the speaker. We changed pro gram sources, and it came again. As in the case of the Wharfedale, we wound up with the speaker leads disconnected, and still there was a knock. I took the back off the speaker, as I had at the store, and checked it again from stem to stern.

Later, when his wife served coffee, she mentioned casually that the china in the cupboard rattled occasionally, for no good reason. We put both phenomena down to poltergeists.

One of my favorite customers was a South American playboy who had decided to make a career at Columbia University as a perpetual student. Alfredo was dark, handsome and loaded, which may help to explain why he had so many girlfriends. As a token of his esteem, each time he'd move in with a new lady-which seemed to be every three months or so-he'd pre sent her with a new hi-fi system. On one occasion, we delivered his latest system to a townhouse on the Upper East Side. The house had a marvelous old spiral staircase, and the system, which included an Electro-Voice Patrician, was to be installed upstairs on the parlor floor. We tried every which way to get it up the stairs and finally did so by lifting it over the railing, taking skin off our knuckles at every turn.

Then came the problem of getting that huge cabinet through the door. In desperation, we cut the corners off the back of the system and eased it through. The mitred corners didn't seem to affect the sound, and Electro Voice adopted our design in later versions of the system.

Another flight of fancy was the Circle-o-Phonic speaker, which used a revolving midrange-tweeter to create an illusion of omni-directionality. This ingenious device used an upward-facing woofer and a 6-inch midrange unit with whizzer cone. The latter, driven by a small clock motor, was mounted vertically just above the woofer. I don't re call the number of revolutions per minute, but some listeners complained it was high enough to make them sea sick, while others detected a.c. hum in the output.

Speakers may be better now, but they're not so much fun. Even by the end of the 1950s, the do-it-yourself tide had ebbed, and much of the eccentricity had been driven out of loudspeaker design by increased knowledge, the rise of the bookshelf speaker, and the requirements of stereo. To this day, I wonder what Marvin (or later occupants of his house, with its living room horn) did when stereo came in.

(Source: Audio magazine, Mar. 1986)

Also see:

The Filter in out Ears (Sept. 1986)

= = = =