The 1982 Winter Consumer Electronics Show was held January 7th through 10th in an unusually cold and blustery Las Vegas. Along with the inclement weather, attendees were also aware of a similar economic climate which made them approach this show very warily. Amid widespread cries of "gloom and doom" about the condition of the consumer electronics industry (and most especially audio components), many feared they would be attending an industry wake. Happily, and much to everyone's surprise, the show was heavily attended. A pervasive optimism in the future of the consumer electronics industry was supported by reports of encouraging dealer-buying activity in almost every component category. However, it should not be construed from this cheerful note that all is well within the industry. Many voices of caution were raised about the recession and the continuing high cost of credit, with oft-repeated admonitions of "Let's see how we make out in the second quarter of this year." The show itself must be considered a transitional event. While there was a generous sprinkling of new product-introductions in most categories, many manufacturers were withholding or delaying major product updating and introductions until the June CES in Chicago. The transitional aspects of the show were more fully expressed by those who are eagerly awaiting the arrival of the digital disc and related digital technologies, which they feel will be a sort of "electronic Moses" that will lead them out of the present economic wilderness.

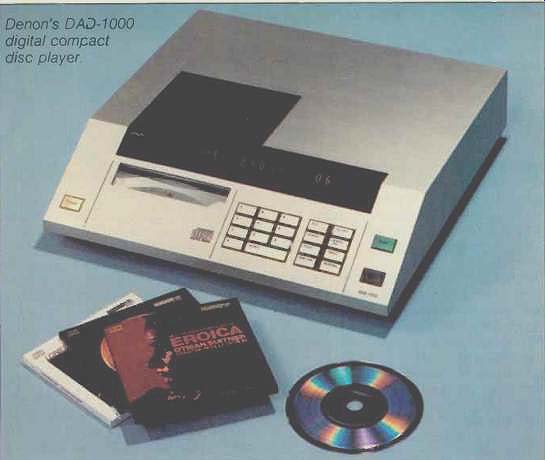

------Denon's DAD-1000 digital compact disc player.

Perhaps the optimism was stimulated by the appearance of a considerable number of prototype models of digital compact disc players as well as other digital audio products. Without meaning to interject a sour note, I must tell you that most of the CD players were non-operational, which probably stemmed more from a lack of software than from electronic or mechanical difficulties. While all the manufacturers of CD players are licensed to use the Sony/Philips DAD technology, there is nothing standard about the players' tracking format or appearance; they vary in size and shape from brand to brand. Prototype CD players shown by Denon, Sony, Aiwa, Yamaha, Sansui, Fisher, Toshiba, and Sanyo have a target-date introduction said to be by early fall in Japan and late fall or early 1983 in the United States. These dates can be met or even moved forward if the compact discs themselves become available on schedule, and CBS/ Sony, Denon, and Polygram anticipate having discs by mid-summer. You can be sure the companies involved will move very cautiously in the matter of software, making certain that the laser read CDs will be reliable and glitch free. Above all, they want to avoid the problems encountered with the laser videodiscs, which suffered from lapses in quality control.

We have reported previously (Audio, April/June, 1981) on the Technics SV-P100 digital audio cassette recorder, which combines PCM LSI chip circuitry with a standard VHS videocassette recorder in a single unit. Hitachi has a recorder similar to the Technics unit. In the January 1982 Audio, I reported on JVC's digital audio cassette recorder.

These three recorders are all intended for the audio consumer and semi-professional markets. The Technics recorder is slated for delivery in the spring of this year, while there are no firm dates for the Hitachi and JVC units.

At this WCES, Sony introduced their PCM-F1 digital audio processor, claiming it makes "the consumer digital age become a reality." (See "Equipment Profile" in our March issue.) Since Sony introduced their PCM-1 digital audio processor back in the mid-'70s, this claim for the PCM-F1 might sound somewhat unusual. But the PCM-F1 is indeed a unique product. It is the world's smallest (8 1/2 x 3 1/8 x 12 inches) and lightest (under 9 lbs.) digital processor. It is also a truly practical system for typical audiophile recording situations, and its price is a far more practical $1,900.00 than the stratospheric $5,000 to $6,000 of the previous PCM units.

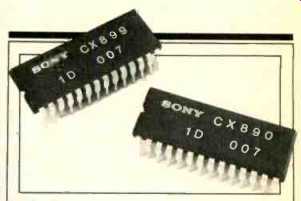

The PCM-F1 processor works with any standard NTSC video recorder U-Matic, VHS or Beta but is specifically intended for use with the Sony SL-2000 Betapak portable video recorder. Both the Betapak and the F1 have shoulder straps, and together they weigh in at a remarkably low 18 lbs. For portable recording, the system can be powered by rechargeable nickel-cadmium batteries. A quick charger and a.c. adaptor unit is available, as are provisions for powering the system via plug-in to a cigarette lighter on car or boat. Beta 500 videocassettes permit up to two hours of digital recording in extended play mode. The small size and weight of the F1 is made possible by LSI chips tor PCM recording and playback, jointly developed by Sony, Sanyo and Toshiba. (The same LSI playback chip will be used in the digital compact disc player.) The F1 uses the EIAJ 14-bit linear quantization, but it can also be switched to 16-bit linear encoding for compatibility with professional digital recorders. Sampling rate is 44.056 kHz/S, which seems strange to incorporate in a new product in light of the 44.1 kHz/S sampling rate proposed as a standard at the 70th AES Convention. Apparently Sony wishes to ensure compatibility with their earlier PCM processors; consider also that Sony's compact disc has a 44.1 kHz/S sampling rate. Perhaps there will be switchable sampling rates in the production model or in an updated version. There are many other features on the F1, not the least of which is a rear panel output which will permit interfacing with EIAJ or 16-bit professional recorders for digital-to-digital copying.

Needless to say, in spite of the digital excitement, analog audio still is our predominant technology and will remain so for quite awhile. Consider, for example, innovative products designed for even more accurate retrieval of the music signals engraved on the venerable LP record.

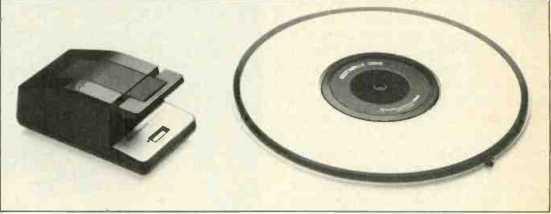

-----Audio-Technica's AT666 Disc Stabilizer.

I have previously reported on the Luxman PD555 turntable, which features a turntable platter with a vacuum suction device that firmly bonds vinyl records to the platter. This vacuum "clamping" thereby removes all warps (whether they be of the "dish" or "pinch" variety) and at the same time eliminates the problem of vinyl resonance. A nifty idea indeed, but at nearly $3,000 hardly a mass-market product. In 1981, Luxman introduced a $695 vacuum platter turntable in which the vacuum was established with a manual pump rather than the elaborate electric pump used on the PD555.

At the WCES, Luxman introduced yet another vacuum platter turntable, the PD300, which again uses a manual pump but has a heavy high-inertia platter. It is priced at $1,000 and, while cheaper than the PD555, will still be beyond the reach of many audiophiles who recognize the virtues of the vacuum system.

-----LSI chips used in Sony's PCM-F1.

Well, take heart friends. Audio-Technica has devised what has to be the ultimate turntable accessory for any dyed-in-the-wool audiophile. To wit a vacuum record clamping system! This is in the form of a finely machined duralumin platter which has rubber vacuum seals around what would be the periphery of the record label and outer edges of the disc. Air channels lead from the vacuum seals to an outlet connection on the rim of the platter, and rubber tubing connects the platter outlet to a hand-operated vacuum pump. On another section of the vacuum platter rim is a small relief valve to "break" the vacuum so that the record may be removed after playback. In use, the original mat (usually rubber) is removed from the turntable's platter, and the vacuum Disc Stabilizer is placed on the spindle of the turntable platter. The AT666 Disc Stabilizer is approximately 3/8 of an inch in thickness and weighs 5 lbs. A few strokes of the vacuum pump are sufficient to establish the vacuum and suck down the record, removing all warpage and the vinyl resonance. Audio-Technica claims the vacuum clamping is equivalent to placing a 550-lb. weight on the record. The vacuum is said to clamp the record in place for an hour, obviously more than sufficient for any standard recording. The AT666 Disc Stabilizer can be used with most turntables, but there are some which have highly compliant suspensions that may be incapable of accepting its 5-lbs weight; there are also some other turntables whose bearings might be damaged by the additional weight. Audio-Technica conducted a clever test in which light, wooden mallets were mechanically tapped on the surface of two vinyl records. One record was placed on a regular turntable platter, and the second record was placed on the AT666 Disc Stabilizer which had been mounted on another similar platter. A contact pickup wire from each turntable was fed into an oscilloscope.

With the standard turntable platter, the tapping of the mallet on the record produced a violent spike on the oscilloscope signal due to vinyl resonance.

The turntable equipped with the vacuum Disc Stabilizer showed no spike in the signal when similarly treated, thus establishing the absence of vinyl resonance. The Disc Stabilizer has to be one of the most clever and useful contributions to the improvement of record playback quality in years. Best of all, it retails for $275.00 complete with vacuum pump, tubing, and a vacuum surface cleaner.

As usual, I could fill pages with reports on new products that caught my eye at the WOES. Next month, I will detail the workings of some of the more interesting items.

-----------

(Source: Audio magazine, Apr. 1982; Bert Whyte )

Also see:

Dr. Thomas Stockham on the Future of Digital Recording (Feb. 1980)

= = = =